Judy Garland Under the Rainbow

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

FY14 Tappin' Study Guide

Student Matinee Series Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life Study Guide Created by Miller Grove High School Drama Class of Joyce Scott As part of the Alliance Theatre Institute for Educators and Teaching Artists’ Dramaturgy by Students Under the guidance of Teaching Artist Barry Stewart Mann Maurice Hines is Tappin’ Thru Life was produced at the Arena Theatre in Washington, DC, from Nov. 15 to Dec. 29, 2013 The Alliance Theatre Production runs from April 2 to May 4, 2014 The production will travel to Beverly Hills, California from May 9-24, 2014, and to the Cleveland Playhouse from May 30 to June 29, 2014. Reviews Keith Loria, on theatermania.com, called the show “a tender glimpse into the Hineses’ rise to fame and a touching tribute to a brother.” Benjamin Tomchik wrote in Broadway World, that the show “seems determined not only to love the audience, but to entertain them, and it succeeds at doing just that! While Tappin' Thru Life does have some flaws, it's hard to find anyone who isn't won over by Hines showmanship, humor, timing and above all else, talent.” In The Washington Post, Nelson Pressley wrote, “’Tappin’ is basically a breezy, personable concert. The show doesn’t flinch from hard-core nostalgia; the heart-on-his-sleeve Hines is too sentimental for that. It’s frankly schmaltzy, and it’s barely written — it zips through selected moments of Hines’s life, creating a mood more than telling a story. it’s a pleasure to be in the company of a shameless, ebullient vaudeville heart.” Maurice Hines Is . -

Summer Classic Film Series, Now in Its 43Rd Year

Austin has changed a lot over the past decade, but one tradition you can always count on is the Paramount Summer Classic Film Series, now in its 43rd year. We are presenting more than 110 films this summer, so look forward to more well-preserved film prints and dazzling digital restorations, romance and laughs and thrills and more. Escape the unbearable heat (another Austin tradition that isn’t going anywhere) and join us for a three-month-long celebration of the movies! Films screening at SUMMER CLASSIC FILM SERIES the Paramount will be marked with a , while films screening at Stateside will be marked with an . Presented by: A Weekend to Remember – Thurs, May 24 – Sun, May 27 We’re DEFINITELY Not in Kansas Anymore – Sun, June 3 We get the summer started with a weekend of characters and performers you’ll never forget These characters are stepping very far outside their comfort zones OPENING NIGHT FILM! Peter Sellers turns in not one but three incomparably Back to the Future 50TH ANNIVERSARY! hilarious performances, and director Stanley Kubrick Casablanca delivers pitch-dark comedy in this riotous satire of (1985, 116min/color, 35mm) Michael J. Fox, Planet of the Apes (1942, 102min/b&w, 35mm) Humphrey Bogart, Cold War paranoia that suggests we shouldn’t be as Christopher Lloyd, Lea Thompson, and Crispin (1968, 112min/color, 35mm) Charlton Heston, Ingrid Bergman, Paul Henreid, Claude Rains, Conrad worried about the bomb as we are about the inept Glover . Directed by Robert Zemeckis . Time travel- Roddy McDowell, and Kim Hunter. Directed by Veidt, Sydney Greenstreet, and Peter Lorre. -

Leslie Caron

COUNCIL FILE NO. t)q .~~f7:; COUNCIL DISTRICT NO. 13 APPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING DIRECT TO CITY COUNCIL The attached Council File may be processed directly to Council pursuant to the procedure approved June 26, 1990, (CF 83-1075-81) without being referred to the Public Works Committee because the action on the file checked below is deemed to be routine and/or administrative in nature: -} A. Future Street Acceptance. -} B. Quitclaim of Easement(s). -} C. Dedication of Easement(s). -} D. Release of Restriction(s) . ..10 E. Request for Star in Hollywood Walk of Fame. -} F. Brass Plaque(s) in San Pedro Sport Walk. -} G. Resolution to Vacate or Ordinance submitted in response to Council action. -} H. Approval of plans/specifications submitted by Los Angeles County Flood Control District. APPROVAL/DISAPPROVAL FOR ACCELERATED PROCESSING: APPROVED DISAPPROVED* Council Office of the District Public Works Committee Chairperson 'DISAPPROVED FILES WILL BE REFERRED TO THE PUBLIC WORKS COMMITTEE. Please return to Council Index Section, Room 615 City Hall City Clerk Processing: Date notice and report copy mailed to interested parties advising of Council date for this item. Date scheduled in Council. AFTER COUNCIL ACTION: ___ -f} Send copy of adopted report to the Real Estate Section, Development Services Division, Bureau of Engineering (Mail Stop No. 515) for further processing. __ ---J} Other: . .;~ ';, PLEASE DO NOT DETACH THIS APPROVAL SHEET FROM THE COUNCIL FILE ACCELERATED REVIEW PROCESS - E Office of the City Engineer Los Angeles California To the Honorable Council Of the City of Los Angeles NOV 242009 Honorable Members: C. D. No. 13 SUBJECT: Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street - Walk of Fame Additional Name in Terrazzo Sidewalk- LESLIE CARON RECOMMENDATIONS: A. -

PDF Download Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall Kindle

JUDY GARLANDS JUDY AT CARNEGIE HALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Manuel Betancourt | 144 pages | 14 May 2020 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781501355103 | English | New York, United States Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall PDF Book Two of her classmates in school were Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. In fact when you see there are tributes to a band that never existed The Rutles and The Muppet Show you could argue this one has run its course Her father was a butcher. Actor Psycho. Actor Alexis Zorbas. The following year, he played the lead character in the first Mickey McGuire short film. Minimal wear on the exterior of item. Self Great Performances. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab Any international shipping and import charges are paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. Actress The Shining. Carol Channing was born January 31, , at Seattle, Washington, the daughter of a prominent newspaper editor, who was very active in the Christian Science movement. He was married to Thomas Kirdahy. Marilyn Monroe was an American actress, comedienne, singer, and model. Actor Pillow Talk. Alone Together. Romantic Sad Sentimental. He first took the stage as a toddler in his parents vaudeville act at 17 months old. Moving to the center of the stage, she sings with emotion as her gloved hand paints the air above her head. He made his first film appearance in Tell Your Friends Share this list:. Kay Thompson Soundtrack Funny Face Sleek, effervescent, gregarious and indefatigable only begins to describe the indescribable Kay Thompson -- a one-of-a-kind author, pianist, actress, comedienne, singer, composer, coach, dancer, choreographer, clothing designer, and arguably one of entertainment's most unique and charismatic Dropped out of high school at the age of fifteen My Profile. -

It's a Conspiracy

IT’S A CONSPIRACY! As a Cautionary Remembrance of the JFK Assassination—A Survey of Films With A Paranoid Edge Dan Akira Nishimura with Don Malcolm The only culture to enlist the imagination and change the charac- der. As it snows, he walks the streets of the town that will be forever ter of Americans was the one we had been given by the movies… changed. The banker Mr. Potter (Lionel Barrymore), a scrooge-like No movie star had the mind, courage or force to be national character, practically owns Bedford Falls. As he prepares to reshape leader… So the President nominated himself. He would fill the it in his own image, Potter doesn’t act alone. There’s also a board void. He would be the movie star come to life as President. of directors with identities shielded from the public (think MPAA). Who are these people? And what’s so wonderful about them? —Norman Mailer 3. Ace in the Hole (1951) resident John F. Kennedy was a movie fan. Ironically, one A former big city reporter of his favorites was The Manchurian Candidate (1962), lands a job for an Albu- directed by John Frankenheimer. With the president’s per- querque daily. Chuck Tatum mission, Frankenheimer was able to shoot scenes from (Kirk Douglas) is looking for Seven Days in May (1964) at the White House. Due to a ticket back to “the Apple.” Pthe events of November 1963, both films seem prescient. He thinks he’s found it when Was Lee Harvey Oswald a sleeper agent, a “Manchurian candidate?” Leo Mimosa (Richard Bene- Or was it a military coup as in the latter film? Or both? dict) is trapped in a cave Over the years, many films have dealt with political conspira- collapse. -

Here Are a Number of Recognizable Singers Who Are Noted As Prominent Contributors to the Songbook Genre

Music Take- Home Packet Inside About the Songbook Song Facts & Lyrics Music & Movement Additional Viewing YouTube playlist https://bit.ly/AllegraSongbookSongs This packet was created by Board-Certified Music Therapist, Allegra Hein (MT-BC) who consults with the Perfect Harmony program. About the Songbook The “Great American Songbook” is the canon of the most important and influential American popular songs and jazz standards from the early 20th century that have stood the test of time in their life and legacy. Often referred to as "American Standards", the songs published during the Golden Age of this genre include those popular and enduring tunes from the 1920s to the 1950s that were created for Broadway theatre, musical theatre, and Hollywood musical film. The times in which much of this music was written were tumultuous ones for a rapidly growing and changing America. The music of the Great American Songbook offered hope of better days during the Great Depression, built morale during two world wars, helped build social bridges within our culture, and whistled beside us during unprecedented economic growth. About the Songbook We defended our country, raised families, and built a nation while singing these songs. There are a number of recognizable singers who are noted as prominent contributors to the Songbook genre. Ella Fitzgerald, Fred Astaire, Rosemary Clooney, Nat King Cole, Sammy Davis Jr., Judy Garland, Billie Holiday, Lena Horne, Al Jolson, Dean Martin, Frank Sinatra, Mel Tormé, Margaret Whiting, and Andy Williams are widely recognized for their performances and recordings which defined the genre. This is by no means an exhaustive list; there are countless others who are widely recognized for their performances of music from the Great American Songbook. -

Storm Rips Manchester, Kills Power

to - MANCHESTER HERALD. Friday. Sept, 6, 1985 MANCHESTER FOCUS SPORTS WEATHER TOWN OF MANCHUT1R CAR8/TRUCK8 LIOAL NOTICI TAG SALES |F0R8ALE Tht Planning ond Zoning Commlulon will hold o public Meanest cut of all Manchester soccer Gloudy, hot today; htorlnd on WtdnMdov, Stpttmbgr II, 1015 at 7:00 P.M. In th t BUSINESS & SERVICE DIRECTORY Town history museum Htorlng Room, Lincoln Ctntar, 494 Main Strott, Manchn- Multi Family — This wee 1980 Ford Fiesta — Hatch ttr, Oonnoctlcut to hear and conildgr the following peti kend beginning Friday. back, standard, radial, has new personality little change Sunday tion*: won’t open this fall can happen to you R ER V il^ FAHITIN6/ I BUIL0IN8/ Too many Items to list, good condtion, A M /F M T H l IiaH TH U T ILITIH DISTRICT ■ ZONING RIGULA- SERVICES Radio, 4 speed. $2,195. l o i j j PAFERHiO CONTRACTINQ 133-140 Strawberry Lane, ... p a g e 2 TION AMENDMENT (E-m - To amend Article II. Section OFFERS! QFEREO Best offer. 646-6876. ... p a g e 3 ... page 111 ... page 15 10.01 to allow municipal office*, police itaflon* and fire Manchester.____________ hou*e> a* permitted uie* provided the (Ite abut* a molor or minor orterlol o* defined by fhe Town'* Plan of Develop Odd lobs. Trucking. Office Machine Repairs Falntmg^ — ComoWe Garage Sale — Friday & ment. and Cleaning-Free pick log - Extertor and lnt» “ nd^emcJ Home reoairs. You name bp dnddellverv.ao Years rior, ceilings rw irrt. ^ e rw m ^ rem^ Saturday, 10am-2pm. ALBERT LINDSAY - SPECIAL EXCEPTION • TAYLOR It, wo do It, Pree esti w . -

Lorna Luft Next to Take the Stage at Live at the Orinda Theatre, Oct. 4

LAMORINDA WEEKLY | Lorna Luft next to take the stage at Live at the Orinda Theatre, Oct. 4 Published Octobwer 3rd, 2018 Lorna Luft next to take the stage at Live at the Orinda Theatre, Oct. 4 By Derek Zemrak Lorna Luft was born into Hollywood royalty, the daughter of Judy Garland and film producer Sidney Luft ("A Star is Born"). She will be bringing her musical talent to the Orinda Theatre at 7:30 p.m. Oct. 4 as part of the fall concert series, Live at the Orinda, where she will be singing the songs her mother taught her. Luft's acclaimed career has encompassed virtually every arena of entertainment. A celebrated live performer, stage, film and television actress, bestselling author, recording artist, Emmy-nominated producer, and humanitarian, she continues to triumph in every medium with critics labeling her one of the most versatile and exciting artists on the stage today. The daughter of legendary entertainer Garland and producer Luft, music and entertainment have always been integral parts of her life. Luft is a gifted live performer, frequently featured on the Lorna Luft Photos provided world's most prestigious stages, including The Hollywood Bowl, Madison Square Garden, Carnegie Hall, The London Palladium, and L'Olympia in Paris. She proves again and again that she's a stellar entertainer, proudly carrying the torch of her family's legendary show business legacy. "An Evening with Lorna Luft: Featuring the Songbook of Judy Garland" is a theatrical extravaganza that melds one of the world's most familiar songbooks with personal memories of a loving daughter. -

The Plagued History of Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, 1965-2009 LAWRENCE SCHULMAN

ARSC JOURNAL VOL. 40, NO. 2 $56&-RXUQDO VOLUME 40, NO. 2 • FALL 2009 )UDQN0DQFLQLDQG0RGHVWR+LJK6FKRRO%DQG·V &RQWULEXWLRQWRWKH1DWLRQDO5HFRUGLQJ5HJLVWU\ 67(9(13(&6(. 7KH3ODJXHG+LVWRU\RI-XG\*DUODQGDQG/L]D0LQQHOOL ´/LYHµDWWKH/RQGRQ3DOODGLXP /$:5(1&(6&+8/0$1 'DYLG/HPLHX[DQGWKH*UDWHIXO'HDG$UFKLYHV -$621.8))/(5 7KH0HWURSROLWDQ2SHUD+LVWRULF%URDGFDVW5HFRUGLQJV FALL 2009 FALL *$5<$*$/2 &23<5,*+7 )$,586( %22.5(9,(:6 6281'5(&25',1*5(9,(:6 &855(17%,%/,2*5$3+< $56&-2851$/+,*+/,*+76 Volume 40, No. 2 ARSC Journal Fall, 2009 EDITOR Barry R. Ashpole ORIGINAL ARTICLES 159 Frank Mancini and Modesto High School Band’s Contribution to the 2005 National Recording Registry STEVEN PECSEK 174 The Plagued History of Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, 1965-2009 LAWRENCE SCHULMAN ARCHIVES 189 David Lemieux and the Grateful Dead Archives JASON KUFFLER DISCOGRAPHY 195 The Metropolitan Opera Historic Broadcast Recordings GARY A. GALO 225 COPYRIGHT & FAIR USE 239 BOOK REVIEWS 281 SOUND RECORDING REVIEWS 317 CURRENT BIBLIOGRAPHY 341 ARSC JOURNAL HIGHLIGHTS 1968-2009 ORIGINAL ARTICLE | LAWRENCE SCHULMAN 7KH3ODJXHG+LVWRU\RIJudy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, In overviewing the ill-fated history of Judy Garland’s last Capitol Records album, Judy Garland and Liza Minnelli “Live” at the London Palladium, recorded on 8 and 15 November WKHDXWKRUHQGHDYRUVWRFKURQLFOHWKHORQJDQGZLQGLQJHYHQWVVXUURXQGLQJLWVÀUVW release on LP in 1965, its subsequent truncated reissues over the years, its aborted release RQ&DSLWROLQLQLWVFRPSOHWHIRUPDQGÀQDOO\LWVDERUWHGUHOHDVHRQ&ROOHFWRU·V&KRLFH -

During the 1930-60'S, Hollywood Directors Were Told to "Put the Light Where the Money Is" and This Often Meant Spectacular Costumes

During the 1930-60's, Hollywood directors were told to "put the light where the money is" and this often meant spectacular costumes. Stuidos hired the biggest designers and fashion icons to bring to life the glitz and the glamour that moviegoers expected. Edith Head, Adrian, Walter Plunkett, Irene and Helen Rose were just a few that became household names because of their designs. In many cases, their creations were just as important as the plot of the movie itself. Few costumes from the "Golden Era" of Hollywood remain except for a small number tha have been meticulously preserved by a handful of collectors. Greg Schreiner is one of the most well-known. His wonderful Hollywood fiolm costume collection houses over 175 such masterpieces. Greg shares his collection in the show Hollywoood Revisited. Filled with music, memories and fun, the revue allows the audience to genuinely feel as if they were revisiting the days that made Hollywood a dream factory. The wardrobes of Marilyn Monroe, Elizabeth Taylor, Julie Andrews, Robert Taylor, Bette Davis, Ann-Margret, Susan Hayward, Bob Hope and Judy Garland are just a few from the vast collection that dazzle the audience. Hollywood Revisited is much more than a visual treat. Acclaimed vocalists sing movie-related music while modeling the costumes. Schreiner, a professional musician, provides all the musical sccompaniment and anecdotes about the designer, the movie and scene for each costume. The show has won critical praise from movie buffs, film historians, and city-wide newspapers. Presentation at the legendary Pickfair, The State Theatre for The Los Angeles Conservancy and The Santa Barbara Biltmore Hotel met with huge success. -

2006 Was Another Year of Great Events, New Releases, and Accolades for and About Judy Garland’S Great Talent and Body of Work

2006 was another year of great events, new releases, and accolades for and about Judy Garland’s great talent and body of work. The biggest news for this past year was the discovery of two of the lost Decca recordings that Judy made in 1935. Thought to be lost forever, these recordings were transferred to digital format and put up for auction (see following page for details). The other big news for the year would have to be the highly successful release of the Judy Garland stamp on what would have been Judy’s 84th birthday, June 10, 2006 (see following page for details) June 2006 could well be remembered as the best “Judy Garland Month” ever! We had the stamp release, two new CDs, over 10 DVDs, the Judy Garland Festival in Minnesota, and more! Plus, The Judy Room has a new look! Beginning in Summer 2006, I began making “vintage magazine covers” the theme of the homepage (see the thumbnails below). These covers reflect the change in seasons and special events or holidays while also fondly looking back to golden age of fan magazines . A BIG THANK YOU to “Alex in Belgium” for his masterful photo colorization. I would like to extend a special thanks and appreciation to Eric Hemphill, Scott Schechter, “tinman”, Donald, and everyone else who has helped to make The Judy Room a success. I hope you all know that I couldn’t do this without you. THANK YOU! Sincerely, Scott Brogan The Judy Room JANUARY 12, 2006: The Recording Industry Association Of America (RIAA) announces their Grammy Hall Of Fame inductees, and the 1956 M-G-M Records soundtrack to The Wizard Of Oz is included. -

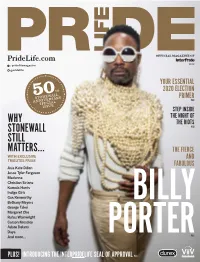

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby.