A Spatial History of Arena Rock, 1964–79 Michael Ethen Schulich School

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download (2399Kb)

A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of Warwick Permanent WRAP URL: http://wrap.warwick.ac.uk/ 84893 Copyright and reuse: This thesis is made available online and is protected by original copyright. Please scroll down to view the document itself. Please refer to the repository record for this item for information to help you to cite it. Our policy information is available from the repository home page. For more information, please contact the WRAP Team at: [email protected] warwick.ac.uk/lib-publications Culture is a Weapon: Popular Music, Protest and Opposition to Apartheid in Britain David Toulson A thesis submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History University of Warwick Department of History January 2016 Table of Contents Acknowledgements………………………………………………………………...iv Declaration………………………………………………………………………….v Abstract…………………………………………………………………………….vi Introduction………………………………………………………………………..1 ‘A rock concert with a cause’……………………………………………………….1 Come Together……………………………………………………………………...7 Methodology………………………………………………………………………13 Research Questions and Structure…………………………………………………22 1)“Culture is a weapon that we can use against the apartheid regime”……...25 The Cultural Boycott and the Anti-Apartheid Movement…………………………25 ‘The Times They Are A Changing’………………………………………………..34 ‘Culture is a weapon of struggle’………………………………………………….47 Rock Against Racism……………………………………………………………...54 ‘We need less airy fairy freedom music and more action.’………………………..72 2) ‘The Myth -

2020 May June Newsletter

MAY / JUNE NEWSLETTER CLUB COMMITTEE 2020 CONTENT President Karl Herman 2304946 President Report - 1 Secretary Clare Atkinson 2159441 Photos - 2 Treasurer Nicola Fleming 2304604 Club Notices - 3 Tuitions Cheryl Cross 0275120144 Jokes - 3-4 Pub Relations Wendy Butler 0273797227 Fundraising - 4 Hall Mgr James Phillipson 021929916 Demos - 5 Editor/Cleaner Jeanette Hope - Johnstone Birthdays - 5 0276233253 New Members - 5 Demo Co-Ord Izaak Sanders 0278943522 Member Profile - 6 Committee: Pauline Rodan, Brent Shirley & Evelyn Sooalo Rock n Roll Personalities History - 7-14 Sale and wanted - 15 THE PRESIDENTS BOOGIE WOOGIE Hi guys, it seems forever that I have seen you all in one way or another, 70 days to be exact!! Bit scary and I would say a number of you may have to go through beginner lessons again and also wear name tags lol. On the 9th of May the national association had their AGM with a number of clubs from throughout New Zealand that were involved. First time ever we had to run the meeting through zoom so talking to 40 odd people from around the country was quite weird but it worked. A number of remits were discussed and voted on with a collection of changes mostly good but a few I didn’t agree with but you all can see it all on the association website if you are interested in looking . Also senior and junior nationals were voted on where they should be hosted and that is also advertised on their website. Juniors next year will be in Porirua and Seniors will be in Wanganui. -

Publicsite.R?Scontinent=USA&Screen=

Results and Description Print Page 1 of 4 Print Results Close Screen Sale 15537 - Life on the Golden Road with the Grateful Dead: The Ram Rod Shurtliff Collection, 8 May 2007 220 San Bruno Avenue, San Francisco, California Prices are inclusive of Buyer's Premium and sales tax (VAT, TVA etc) and may be subject to change. Lot Description Hammer Price 1 A Bob Seidemann mounted-to-board photographic print of The Grateful Dead, $1,680 1971 2 Two color photographs of Jerry Garcia and Bob Weir, circa 1968 $900 3 Five black and white photographs of The Grateful Dead, circa 1969 $780 4 A massive display piece of The Grateful Dead from The Winterland Ballroom, circa $9,600 1966-1978 5 A poster of Pig Pen and Janis Joplin, 1972 $720 6 A Herb Greene signed black and white photograph of The Grateful Dead, 1965, $1,320 1988 7 A Herb Greene signed black and white photograph of Jerry Garcia, 1966, 1980s $960 8 A Herb Greene signed limited edition black and white photograph of The Grateful $2,400 Dead with Bob Dylan, 1987, 1999 9 A Herb Greene signed black and white photograph of The Grateful Dead and Bob $1,440 Dylan, 1987, 1999 10 A Herb Greene signed and numbered limited edition poster of Jerry Garcia, 1966, $900 2003 11 A group of photographs of The Grateful Dead, 1960s-1990s $480 12 A William Smythe signed color photograph of Phil Lesh, 1983 $360 13 A Bob Thomas group of original paintings created for The Grateful Dead album $87,000 jacket "Live/Dead," 1969 14 An RIAA gold record given to The Grateful Dead for "Grateful Dead" (aka "Skull $11,400 and -

RADIATION SAFETY OFFICE Table of Contents

Center for Radiological Research − 630 W. 168th St., New York, NY 10032 − http://crr-cu.org ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Eric J. Hall Director Howard B. Lieberman Editor Jinshuang Lu Assistant Editor CENTER FOR RADIOLOGICAL RESEARCH • ANNUAL REPORT 2007 Table of Contents CONTENTS.................................................................................................................................................................................1 COLLABORATING DEPARTMENTS AND INSTITUTIONS....................................................................................................4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT OF SUPPORT.....................................................................................................................................4 RELATED WEB SITES..............................................................................................................................................................4 INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................................................................................5 STAFF NEWS .............................................................................................................................................................................6 COLUMBIA COLLOQUIUM AND LABORATORY SEMINARS..............................................................................................7 STAFF LISTING .........................................................................................................................................................................8 -

George Harrison

COPYRIGHT 4th Estate An imprint of HarperCollinsPublishers 1 London Bridge Street London SE1 9GF www.4thEstate.co.uk This eBook first published in Great Britain by 4th Estate in 2020 Copyright © Craig Brown 2020 Cover design by Jack Smyth Cover image © Michael Ochs Archives/Handout/Getty Images Craig Brown asserts the moral right to be identified as the author of this work A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. By payment of the required fees, you have been granted the non-exclusive, non-transferable right to access and read the text of this e-book on-screen. No part of this text may be reproduced, transmitted, down-loaded, decompiled, reverse engineered, or stored in or introduced into any information storage and retrieval system, in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of HarperCollins. Source ISBN: 9780008340001 Ebook Edition © April 2020 ISBN: 9780008340025 Version: 2020-03-11 DEDICATION For Frances, Silas, Tallulah and Tom EPIGRAPHS In five-score summers! All new eyes, New minds, new modes, new fools, new wise; New woes to weep, new joys to prize; With nothing left of me and you In that live century’s vivid view Beyond a pinch of dust or two; A century which, if not sublime, Will show, I doubt not, at its prime, A scope above this blinkered time. From ‘1967’, by Thomas Hardy (written in 1867) ‘What a remarkable fifty years they -

Wade Gordon James Nelson Concordia University May 1997

Never Mind The Authentic: You Wanted the Spectacle/ You've Got The Spectacle (And Nothing Else Matters?) Wade Gordon James Nelson A Thesis in The Department of Communication Studies Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts ai Concordia University Montreal, Quebec, Canada May 1997 O Wade Nelson, 1997 National Library Bibliothèque nationale 191 of Canada du Canada Acquisitions and Acquisitions et Bibliographie Services services bibliographiques 395 Wellington Street 395, rue Weliington Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Ottawa ON KIA ON4 Canada Canada Your hie Votre réference Our file Notre reldrence The author has granted a non- L'auteur a accordé une licence non exclusive licence allowing the exclusive permettant à la National Library of Canada to Bibliothèque nationale du Canada de reproduce, loan, distribute or sell reproduire, prêter, distribuer ou copies of ths thesis in microform, vendre des copies de cette thèse sous paper or electronic formats. la forme de microfiche/fh, de reproduction sur papier ou sur fomat électronique. The author retains ownership of the L'auteur conserve la propriété du copyright in thi s thesis. Neither the droit d'auteur qui protège cette thése. thesis nor substantiai extracts fiom it Ni la thèse ni des extraits substantiels may be printed or otherwise de celle-ci ne doivent être imprimés reproduced without the author's ou autrement reproduits sans son permission. autorisation. ABSTRACT Never Mind The Authentic: You Wanted The Spectacle/ Y ou've Got The Spectacle (And Nothing Else Matters?) Wade Nelson This thesis examines criteria of valuation in regard to popular music. -

PDF Download Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall Kindle

JUDY GARLANDS JUDY AT CARNEGIE HALL PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Manuel Betancourt | 144 pages | 14 May 2020 | Bloomsbury Publishing PLC | 9781501355103 | English | New York, United States Judy Garlands Judy at Carnegie Hall PDF Book Two of her classmates in school were Mickey Rooney and Judy Garland. In fact when you see there are tributes to a band that never existed The Rutles and The Muppet Show you could argue this one has run its course Her father was a butcher. Actor Psycho. Actor Alexis Zorbas. The following year, he played the lead character in the first Mickey McGuire short film. Minimal wear on the exterior of item. Self Great Performances. Learn More - opens in a new window or tab Any international shipping and import charges are paid in part to Pitney Bowes Inc. Actress The Shining. Carol Channing was born January 31, , at Seattle, Washington, the daughter of a prominent newspaper editor, who was very active in the Christian Science movement. He was married to Thomas Kirdahy. Marilyn Monroe was an American actress, comedienne, singer, and model. Actor Pillow Talk. Alone Together. Romantic Sad Sentimental. He first took the stage as a toddler in his parents vaudeville act at 17 months old. Moving to the center of the stage, she sings with emotion as her gloved hand paints the air above her head. He made his first film appearance in Tell Your Friends Share this list:. Kay Thompson Soundtrack Funny Face Sleek, effervescent, gregarious and indefatigable only begins to describe the indescribable Kay Thompson -- a one-of-a-kind author, pianist, actress, comedienne, singer, composer, coach, dancer, choreographer, clothing designer, and arguably one of entertainment's most unique and charismatic Dropped out of high school at the age of fifteen My Profile. -

An American Band by Tibbieb

An American Band By TibbieB Dear Readers, A summers ago, a group of S&H sibs and I met in the Great Smokey Mountains for a few days of watching episodes and sharing our obsession for the boys. While watching “The Specialist” late one night, we noticed Starsky was wearing a t-shirt with something printed on the front. Ever desperate for any minute detail about the private lives of our heroes, we pursued the clue with a fervor equal to Sherlock Holmes tracking down Dr. Moriarty. Thank God for that marvelous invention on the DVD player the zoom! JackieH, always up to a challenge, maneuvered and manipulated the device until the words emblazoned on the t-shirt miraculously flashed on the screen before our eyes: “We’re An American Band.” “I know what that is!” I shouted to the others. “Grand Funk Railroad! That’s one of Grand Funk’s biggest hits!” Who would have taken Starsky for a Grand Funk Railroad fan? He was a rocker a hard rocker, no less! Until that moment, we had had little insight into his taste in music (aside from disco music, Jim Croce, and a little “Black Bean Soup”). We knew Starsky played the guitar, but had been treated to only a smattering of his musical ability in “The Avenger.” Could it be true? Starsky liked hardcore rock-and-roll? We pontificated on this for hours and, on the following day, rushed into town in search of Grand Funk’s CD by the same title. It wasn’t easy, but we finally returned home from a hard day of shopping in Gatlinburg, Tennessee, Londonmaid proudly clutching the trophy in her hand. -

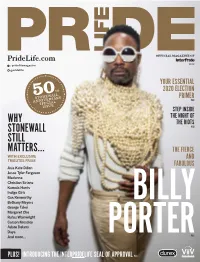

Why Stonewall Still Matters…

PrideLife Magazine 2019 / pridelifemagazine 2019 @pridelife YOUR ESSENTIAL th 2020 ELECTION 50 PRIMER stonewall P.68 anniversaryspecial issue STEP INSIDE THE NIGHT OF WHY THE RIOTS STONEWALL P.50 STILL MATTERS… THE FIERCE WITH EXCLUSIVE AND TRIBUTES FROM FABULOUS Asia Kate Dillon Jesse Tyler Ferguson Madonna Christian Siriano Kamala Harris Indigo Girls Gus Kenworthy Bethany Meyers George Takei BILLY Margaret Cho Rufus Wainwright Carson Kressley Adore Delano Daya And more... PORTERP.46 PLUS! INTRODUCING THE INTERPRIDELIFE SEAL OF APPROVAL P.14 B:17.375” T:15.75” S:14.75” Important Facts About DOVATO Tell your healthcare provider about all of your medical conditions, This is only a brief summary of important information about including if you: (cont’d) This is only a brief summary of important information about DOVATO and does not replace talking to your healthcare provider • are breastfeeding or plan to breastfeed. Do not breastfeed if you SO MUCH GOES about your condition and treatment. take DOVATO. You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should ° You should not breastfeed if you have HIV-1 because of the risk of passing What is the Most Important Information I Should HIV-1 to your baby. Know about DOVATO? INTO WHO I AM If you have both human immunodeficiency virus-1 (HIV-1) and ° One of the medicines in DOVATO (lamivudine) passes into your breastmilk. hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection, DOVATO can cause serious side ° Talk with your healthcare provider about the best way to feed your baby. -

Peter F. Andrews Sportswriting and Broadcasting Resume [email protected] | Twitter: @Pfandrews | Pfandrews.Wordpress.Com

Peter F. Andrews Sportswriting and Broadcasting Resume [email protected] | Twitter: @pfandrews | pfandrews.wordpress.com RELEVANT EXPERIENCE Philly Soccer Page Staff Writer & Columnist, 2014-present: Published over 100 posts, including match reports, game analysis, commentary, and news recaps, about the Philadelphia Union and U.S. National Teams. Covered MLS matches, World Cup qualifiers, Copa America Centenario matches, and an MLS All-Star Game at eight different venues across the United States and Canada. Coordinated the launch of PSP’s Patreon campaign, which helps finance the site. Appeared as a guest on one episode of KYW Radio’s “The Philly Soccer Show.” Basketball Court Podcast Host & Producer, 2016-present: Produced a semi-regular podcast exploring the “what-ifs” in the history of the National Basketball Association, presented in a humorous faux-courtroom style. Hosted alongside Sam Tydings and Miles Johnson. Guests on the podcast include writers for SBNation and SLAM Magazine. On The Vine Podcast Host & Producer, 2014-present: Produced a weekly live podcast on Mixlr during the Ivy League basketball season with writers from Ivy Hoops Online and other sites covering the league. Co-hosted with IHO editor-in- chief Michael Tony. Featured over 30 guests in three seasons. Columbia Daily Spectator Sports Columnist, Fall 2012-Spring 2014: Wrote a bi-weekly column for Columbia’s student newspaper analyzing and providing personal reflections on Columbia’s athletic teams and what it means to be a sports fan. Spectrum Blogger, Fall 2013: Wrote a series of blog posts (“All-22”) which analyzed specific plays from Columbia football games to help the average Columbia student better understand football. -

Marzo 2016 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1

Número 58 - marzo 2016 CULTURA BLUES. LA REVISTA ELECTRÓNICA Página | 1 Contenido Directorio PORTADA El blues de los Rolling Stones (1) …………………………...... 1 Cultura Blues. La Revista Electrónica CONTENIDO - DIRECTORIO ..……………………………………..…….. 2 “Un concepto distinto del blues y algo más…” EDITORIAL Al compás de los Rolling Stones (2) .......................…. 3 www.culturablues.com SESIONES DESDE LA CABINA Los Stones de Schrödinger Número 58 – marzo de 2016 (3) ..…………………………………………..……..…..………………………………………... 5 Derechos Reservados 04 – 2013 – 042911362800 – 203 Registro ante INDAUTOR DE COLECCIÓN El blues de los Rolling Stones. Parte 3 (2) .……..…8 COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL ¿Quién lo dijo? 4 (2) ………….…. 17 Director general y editor: José Luis García Fernández BLUES EN EL REINO UNIDO The Rolling Stones – Timeline parte I (4) .......................................... 21 Subdirector general: José Luis García Vázquez ESPECIAL DE MEDIANOCHE Fito de la Parra: sus rollos y sus rastros (5) ……………….…….…..…….…. 26 Programación y diseño: Aida Castillo Arroyo COLABORACIÓN ESPECIAL La Esquina del Blues y otras músicas: Blues en México, recuento Consejo Editorial: de una década I (6) …………………………………………………………………….…. 34 María Luisa Méndez Flores Mario Martínez Valdez HUELLA AZUL Castalia Blues. Daniel Jiménez de Viri Roots & The Rootskers (7, 8 y 9) ………………………………………..……………..….… 38 Colaboradores en este número: BLUES A LA CARTA 10 años de rock & blues (2) .……………..... 45 1. José Luis García Vázquez CULTURA BLUES DE VISITA 2. José Luis García Fernández Ruta 61 con Shrimp City Slim (2 y 9) ................................................. 52 3. Yonathan Amador Gómez 4. Philip Daniels Storr CORTANDO RÁBANOS La penca que no retoña (10) ............ 55 5. Luis Eduardo Alcántara 6. Sandra Redmond LOS VERSOS DE NORMA Valor (11) ..………………………………… 57 7. María Luisa Méndez Flores 8. -

Holly Man, Teacher Held on Child Porn Charges

CASH USA MANAGER NICHOLAS SERGES THE STORIES BEHIND OUR AREA BUSINESSES FEATURED SECTION BEGINNINGS PART 1 INCLUDED WITH THIS EDITION $1.00 Fall Sports Preview SUNDAY EDITION An in-depth look at the Fenton, Holly, Lake Fenton and Linden football teams. Featured mini-tab section Weekend VOL. 22 NO. XXXIV SUNDAY, AUGUST 23, 2015 2012 - 2013 - 2014 NEWSPAPER OF THE YEAR Holly man, Grand Funk Railroad’s teacher held Mark Farner familiar on child porn with Fenton, Page 3A charges nAdmits to Mark Farner, '70s possessing 600 images including children involved in LINKEDIN PHOTO incest and Eric Junod bondage By Sharon Stone [email protected]; 810-433-6786 A 38-year-old Holly Township man is being temporarily detained on pending federal charges of distribut- ing, receiving and possessing child pornography. Eric Junod was recently fired from his job as part-time assistant band instructor at Troy Athens High School See PORNOGRAPHY on 6A Seminary to come Argentine opens Topps building down shortly firstcanoe launch is toppled after Labor Day Community members Demolition of the The 147-year-old can launch canoes, old Topps building building, also known kayaks, and stand-up began Friday morning as the Old Baptist paddleboards on the in Fenton. LaJoice Ministers house, will Shiawassee River from Enterprises will be be be demolished at the McCaslin Lake putting in a mixed- a cost of $48,900. Road Launch. use development. Page 8A Page 13A Page 19A Can some wordsmith Study after study shows A few weeks ago, King wrote TEXT out there please tell me a that dogs have the same men- an excellent column on the sights COMMENT YOUR ‘‘ word that rhymes ‘‘ tal capacity as a 2- ‘‘ and sounds of Fenton’s OF THE WEEK with Hillary, a word to 3-year-old child.