HERODOTUS Volume XXX • Spring 2020 Stanford University Department of History HERODOTUS Volume XXX

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SJT Volume 15 Issue 1 Cover and Front Matter

SCOTTISH JOURNAL 0 THEOLOGY Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 28 Sep 2021 at 10:40:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0036930600009844 THE COMING REFORMATION Geddes MacGregor "The analysis of Protestantism is acid and severe but warranted. Outlined skilfully and with learning ... a valuable and stimulating book." E. GORDON RUPP, Time and Tide. i;s. from HODDER AND STOUGHTON HUDSON TAYLOR AND MARIA J. C. Pollock "It is a tribute to the author that he has not only succeeded in writing a very thrilling biography, but has been able to supply fresh information." Church of England Newspaper, illus. 16s. GUILT AND GRACE A Psychological Study Paul Tournier The insights of modern psychology and of enlightened Christian teaching are used to illuminate each other in this lucid study, which shows the practical bearing the Christian faith has upon personal relationships. 21s. KAKAMORA Charles E. Fox "For sympathetic insight into the character of the Melanesian people this book . would be hard to beat... he has told his story with verve, gusto and humour ... an excellent book." Church Times, irj. SON OF MAN Leslie Paul ' 'Mr Paul's life of Christ is alive from beginning to end ... a welcome contribution to the debate going on in so many minds today: What think ye of Christ?" DR. w. R. MATTHEWS, Daily Telegraph. Us. Downloaded from https://www.cambridge.org/core. IP address: 170.106.40.40, on 28 Sep 2021 at 10:40:20, subject to the Cambridge Core terms of use, available at https://www.cambridge.org/core/terms. -

DAYS of VENGEANCE but When You See Jerusalem Surrounded by Armies, Then Know That Her Desolation Is at Hand

THE DAYS OF VENGEANCE But when you see Jerusalem surrounded by armies, then know that her desolation is at hand. Then let those who are in Judea flee to the mountains, and [et those who are in the midst of the city depart, and let not those who are in the country enter the city; because these are the Days of Vengeance, in order that all things which are written may be fu@lled. Luke 21:20-22 THE DAYS OF VENGEANCE An Exposition of the Book of Revelation David Chilton Dominion Press Ft. Worth, Texas Copyright @ 1987 by Dominion Press First Printing, January, 1987 Second Printing, Decembefi 1987 Third Printing, March, 1990 All rights reserved. Written permission must be secured from the publisher to use or reproduce any part of this book, except for brief quotations in critical reviews or articles. Published by Dominion Press P.O. Box 8204, Ft. Worth, Texas 76124 Typesetting by Thoburn Press, Box 2459, Reston, VA 22090 Printed in the United States of America Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 86-050798 ISBN 0-930462-09-2 To my father and mother TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD by Gordon J. Wenham . ix AUTHOR’S PREFACE . xi PUBLISHER’S PREFACE by Gary North . xv INTRODUCTION . 1 Part One: PREAMBLE: THE SON OF MAN (Revelational) . 49 l. King of Kings . 51 Part Two: HISTORICAL PROLOGUE:THE LETTERS TO THE SEVEN CHURCHES(Revelation2-3). 85 2. The Spirit Speaks to the Church: Overcome! . 93 3. The Dominion Mandate . ...119 Part Three: ETHICAL STIPULATIONS: THE SEVEN SEALS(Revelation 4-7) . -

50 Anniversary

TheThe American-ScottishAmerican-Scottish FoundationFoundation ® 5050 ththAnniversaryAnniversary && ® WallaceWallace AwardAward GalaGala DinnerDinner TheThe UniversityUniversity Club,Club, NewNew YorkYork City,City, OctoberOctober 23,23, 20062006 Walkers Shortbread Congratulates the American Scottish Foundation on their 50th Anniversary. Visit our website to learn more about Walkers Shortbread: www.walkersus.com Baked fresh in our family bakery in the Scottish highlands. FREE shipping on orders over $20. Enter code ASF at checkout. Walkers Deliciously pure. Purely delicious. www.walkersus.com Gala Program wp Cocktail Reception Welcome Presentation of Wallace Award® to Euan Baird Dinner Live Auction Dessert Anniversary Toast 8 1 Mr Alan L Bain October 2006 President The American-Scottish Foundation Inc Scotland House 575 Madison Avenue, Suite 1006 New York NY 100022-2511 USA Dear Mr. Bain, I am delighted to add my congratulations to the American-Scottish Foundation on its 50th anniversary dinner. The American-Scottish Foundation has made a significant contribution to raising the awareness of both traditional and contemporary Scotland in the United States. The Foundation has helped to make Tartan Week become the most successful promotion of Scotland overseas and its involvement in larger initiatives, such as the Scottish Coalition, has been of great benefit to Scotland. I have had the pleasure of meeting many members of the American-Scottish Foundation during my time as First Minister, and I am sorry that I cannot be there to celebrate -

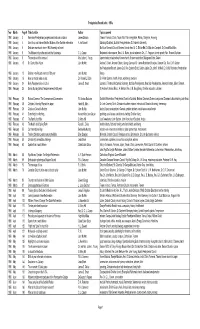

American Clan Gregor Society Marshall Magruder Memorial Library List of Books (Alphabetical by Author)

American Clan Gregor Society Marshall Magruder Memorial Library List of Books (Alphabetical by Author) Adam and Charles Black (Firm) Black's picturesque tourist of Scotland / by Black, Adam and Charles. Edinburgh : A. and C. Black, 1867. University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - DA870 - .B626 1867 __________________ Adam, Frank. The clans, septs, and regiments of the Scottish Highlands. Edinburgh : Johnston & Bacon, 1970. University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - DA880.H6A6 1970 __________________ Adam, Robert James. Papers on Sutherland estate management, 1802-1816, edited by R. J. Adam. Edinburgh : printed for the Scottish History Society by T. and A. Constable, 1972. University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - DA880.A33 1972 __________________ Adams, Ian H. Directory of former Scottish commonties / edited by Ian H. Adams. Edinburgh : Scottish Record Society, 1971. University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - HD1289.S35 - A63 __________________ Mac Gregor's second gathering / American Clan Gregor Society. Olathe, KS : Cookbook Publishers, Inc., 1990. University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - TX714 - .M33 1990 __________________ Mac Gregors gathering recipes / American Clan Gregor Society. Silver Spring, MD : The Society, 1980. University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - TX714 - .M33 1980 __________________ American Clan Gregor Society. American Clan Gregor : rules and regulations 1910. Washington, D.C. : Law Reporter Printing Co., 1911. University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - CS71.G7454 - 1910 __________________ Year-book of American Clan Gregor Society : containing the proceedings at the gatherings of 19... 1 [Washington, D.C. : American Clan Gregor Society, 1910- University of Baltimore : Special Collections American Clan Gregor - CS71 - .M148 __________________ American Clan Gregor Society. -

Reincarnation As a Christian Hope

REINCARNATION AS A CHRISTIAN HOPE Christian teaching about what the Creed calls 'the life of the world to come' is more muddled than is any other part of traditional doctrine. Professor Mac· Gregor notes at the outset the uneasiness that many of us in the West feel about the notion of reincarnation. It is often misunderstood in a primitivistic and magical way; even in its most ethical and developed forms it seems to fit Chris· tianity about as badly as would a stupa or pagoda atop a Gothic church. Yet the promise of resurrection, that most central and orthodox of all Christian doctrines, is the promise of a form of reincarnation. Most of the difficulties, philosophical and theological, that apply to the one (e.g. memory and continuity) affect the other no less. MacGregor also uses reincarnation as an interpretation of the Anglican doctrine of purgatory as a place of growth. Dr MacGregor proposes that a careful examination of the roots of rein· carnationist theory in the West and its immense and pervasive influence in Christian literature, not least during and since the Italian Renaissance, will show how reincarnation may not only fit into, but also immeasurably enrich, our Christian hope so as to make even educated conservative opinion hospitable to it. He asks both that theologians will consider his proposal with the seriousness he believes it merits and that the average Christian whom he has especially in mind will find it as exciting and rewarding as he does. Geddes MacGregor, D es L (Sorbonne), D Phil, DD (Oxford), LL B (Edin· burgh), is Emeritus Distinguished Professor of Philosophy, University of Southern California, where he was Dean of the School of Religion. -

JOHN KNOX AFTER FOUR HUNDRED YEARS by W. Stanford

JOHN KNOX AFTER FOUR HUNDRED YEARS by W. Stanford Reid The year 1972 is the year in which we commemorate the death of John. Knox, the Scottish Reformer. For this reason it is probably a good thing to look back over the intervening centuries to gain perspective on his work. In estimating his achievements and attempting to understand them, we may well learn something, not only of him but also of ourselves. Indeed, we may even gain some knowledge that will help us in our own endeavours in the latter part of the twentieth century. Interpretations o f Knox since 1572 Ever since Knox's own day many different interpretations of him and his work have been made. Some have been strongly in his favor, apparently with the view that he could do nothing wrong. Others have been just as far in the opposite direction, with the attitude that he could do nothing right. A few have attempted to occupy a middle ground, but they have not been entirely successful in convincing either his foes or his friends, for Knox, as during his life time, has evoked strong emotions that incline to be extreme rather than moderate. In the case of the reformer, neutrality has been almost unknown. Those who were against him in his own day adopted this stance sometimes because of his very brusqueness, even violence of language and policy. As Sir Thomas Randolph reported to Sir William Cecil in 1562 when it was rumored that Queen Mary would become an Anglican: I have not conferred with Mr. -

History and Theology of the Eldership Within the Church of Scotland

AN INTRODUCTION TO THE HISTORY AND THEOLOGY OF THE ELDERSHIP WITHIN THE CHURCH OF SCOTLAND DECEMBER 2015 REVD DR ALEXANDER FORSYTH HOPE TRUST RESEARCH FELLOW, NEW COLLEGE, UNIVERSITY OF EDINBURGH 2 INTRODUCTION The Report of the Mission and Discipleship Council to the General Assembly of 2014 notes the creation of the Eldership Working Group following the 2011 Assembly, whose purpose is ‘to look at patterns and models of Eldership currently in use across the Church today and to bring to the attention of the General Assembly ways in which these could be shared, reflected upon and in some cases adapted to encourage appropriate practice in our changing contexts’.1 Deliverance 21 of the 2014 Report asks the General Assembly to commend the Kirk Sessions for their participation in widespread and detailed consultations nationally, and ‘their desire to enhance the effectiveness of the office of elder’. This paper has been commissioned in that context to set out an introduction to the history and theology of the eldership within the Presbyterian tradition in Scotland, in order to contribute to the process of reflection, assessment and potential reform of the role and duties of eldership. The paper seeks to highlight aspects of eldership which in times past defined its existence, a recovery of which may be beneficial. It also highlights the area of missional focus as a potential ‘supra-narrative’ for the future of the eldership, which might provide an lens through which to view decisions as to the purposes and duties of the office, beyond a concentration on narrower areas of contention, such as ‘spiritual’ status or ordination. -

Historical Theology to 1900

How The Christian Church Got To Where It Is A Sketch of Historical Theology to 1900 H. Carl Shank How The Christian Church Got To Where It Is: A Sketch of Historical Theology to 1900 Copyright © 2018 by H. Carl Shank. All rights reserved. ISBN 978-0-359-22145-5 Permission to photocopy any portion of this book for ministry purposes must be obtained from the author. Any photocopy must include copyright credits as stated above. Most Scripture references are taken from the the ESV Bible, © 2001 by Crossway, a ministry of Good News Publishers. All references used by permission from the publishers. All rights reserved. Cover design: H. Carl Shank. Background photo montage from historical sites in England and Scotland from a personal history tour in 2017. Historical figures via public domain from bottom right: Saint Augustine of Hippo, William Tyndale, Martin Luther, John Calvin, and John Wesley. First Edition 2018. Second Edition 2019. Printed in the United States of America 2 About the Author In addition to his M.Div. and Th.M. (systematics) work, H. Carl Shank has been a youth, associate, solo, staff and lead pastor in over forty years of church ministry, pastoring beginning and established congregations in Pennsylvania, Delaware, Maryland, Virginia and New York state. His passion for leadership development has resulted in mentoring numerous pastors, teaching in a number of local Bible institutes as well as serving as an adjunct faculty member of The King’s College, and training InterVarsity leaders on the East Coast. Carl has been regularly sought out for his acknowledged gifts of discernment and wisdom in dealing with church issues. -

Concoll()Ia Theological Monthly

Concoll()ia Theological Monthly NOVEMBER • 1958 BOOK REVIEW All books reviewed in this periodical may be procured from or through Concordia Pub lishing House, 3558 South Jefferson Avenue, St. Louis 18, Missottri. DIE CHRISTOLOGIE DES NEUEN TESTAMENTS. By Oscar Cullmann. Tiibingen: J. c. B. Mohr, 1957. viii and 352 pages. Cloth. DM 12. In this book Cullmann aims to go behind the church's later emphasis on the natures of Christ to the New Testament's interest in His activity. It is not so much a study in the locus of Christology as an attempt to determine exactly how the New Testament pictures the person of Jesus Christ. For convenient handling of the material Cullmann takes the principal titles of our Lord and treats them under four main headings: (a) those that apply to Jesus' earthly work (Prophet, Suffering Servant, and High Priest); (b) those that apply to Jesus' future work (Messiah, Son of Man); (c) those that apply to His present work (Lord, Savior) ; and (d) those that apply to His pre-existence (Logos, Son of God, God). This methodological approach is not without its hazards, but Cullmann overcomes the problem of overlap quite skillfully. His critical acumen, as well as his wariness of presuppositions of any variety, is evident on every page. His courageous insistence on a proper distinction between parallel and genetic phenomena, especially in connection with the %UQLO~ and ),6yo~ concepts, should prove heartening to all students who have sensed the weaknesses in presentations like that of Bousset, but have been unable to locate the Achilles' heel. -

Presbyterian Record Index 1950S

Presbyterian Record Index - 1950s Year Month Page # Title of article Author Topics covered 1950 January 3 Formosan Presbyterians progress amid national confusion James Dickson Taiwan, Formosa, China, Taipeh, Red Tide, immigration, Paktau, Siang-lian, Ho-peng 1950 January 4 John Knox and Andrew Melville: Builders of the Scottish reformation A. Ian Burnett Edinburgh Scotland, Scottish Presbyterianism, St. Andrew's University 1950 January 5 Dedicate new church where 1950 Assembly will meet MacVicar Memorial Church Montreal, church fires, Dr. C. Ritchie Bell, Dr. Malcolm Campbell, Dr. Donald MacMillan 1950 January 6 The Moderator tours the west and the Kootenays C. L. Cowan Mistawasis Indian reserve, Rev. J. A. Munro, church extension, Dr. J. T. Ferguson, church growth, Rev. Thomas Roulston 1950 January 9 The exodus and the remnant Mrs. Luther L. Young Japan mission, missionaries, Korean church, Korean repatriation, Mukogawa, Kobe, Osaka 1950 January 13 Dr. Grant of the Yukon John McNab Andrew S. Grant, Almonte Ontario, George Carmack, Dr. James Robertson, Klondyke, Dawson City, Rev. C. W. Gordon the Presbyterian Record, James Croil, Rev. Ephraim Scott, Golden Jubilee, Dr. John T. McNeill, Dr. W. M. Rochester, Presbyterian 1950 January 15 Editorial - the Record enters its 75th year John McNab history 1950 January 16 How our minds make us sick Dr. Russell L. Dicks Dr. Walter Cannon, health, illness, well-being, emotions 1950 January 24 Early Presbyterianism in U.S.A. James D. Smart Leonard J. Trinterud McCormick Seminary, Old Side Presbyterians, New Side Presbyterians, American history, Gilbert Tennent 1950 February 35 Sarnia Sunday School Teacher serves for 58 years St. -

The Christening of Karma

The Christening of Karma The Secret of Evolution By Geddes MacGregor © Copyright by Geddes MacGregor, 1984. Published in 1984 by The Theosophical Publishing House Wheaton, III. U.S.A. Contents 1 Evolution and Karma 1 2 Evolution as Universal 9 3 The Moral Dimension of Evolution 25 4 Grace Surprises 40 5 The Christening of Karma 52 6 Karma and Freedom 63 7 Evolution, Karma, and Rebirth 70 8 Human Sexuality and Evolution 80 9 Stages in Spiritual Development 93 10 Our Kinship with All Forms of Life 104 11 Evolution and God 115 12 Evolution and the ʺBlessed Assuranceʺ 125 13 Karma, Evolution, and Destiny 134 Chapter One Evolution and Karma Evolution is not a force but a process: not a cause but a law. John Morley. On Compromise What avails it to fight with the eternal laws of mind, which adjust the relation of all persons to each other, by the mathematical measure of their havings and beings? Emerson. Spiritual Laws In the course of my teaching and lecturing in universities and other institutions, I have discovered during the past decade or more an increasing interest in the concept of karma. It comes out in discussion at the slightest provocation and indeed sometimes with no detectable provocation at all. It is not always well understood. Too often it is so ill understood as to be taken for a kind of fatalism, which it certainly is not, being on the contrary a freewill doctrine, although it is much else besides. Yet, understood well or badly, it commands a lively interest, not least on the part of young people who twenty years ago would not have generally found it so challenging to their outlook on life. -

Charlotte Dawber Phd Thesis

CLOTHING THE SAINTS AND FURNISHING HEAVEN : A PURITAN LEGACY IN THE NEW WORLD Charlotte Dawber A Thesis Submitted for the Degree of PhD at the University of St Andrews 1996 Full metadata for this item is available in St Andrews Research Repository at: http://research-repository.st-andrews.ac.uk/ Please use this identifier to cite or link to this item: http://hdl.handle.net/10023/15414 This item is protected by original copyright Clothing the Saints & Furnishing Heaven: A Puritan Legacy in the New Wcitd Charlotte Dawber ProQuest Number: 10167302 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a com plete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. uest. ProQuest 10167302 Published by ProQuest LLC(2017). Copyright of the Dissertation is held by the Author. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. ProQuest LLC. 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106- 1346 -------------------------- ------------- 'M an looketh on the outward appearance but the Lord looketh on the heart.' I Samuel 16 : 7 DECLARATIONS 3 I, Charlotte Elizabeth Jane Dawber, hereby certify that this thesis, which is approximately 100,000 words in length, has been written by me, that it is the record of work carried out by me and that it has not been submitted in any previous application for a higher degree.