Dictionary of Moscow Conceptualism Dictionary Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

El Lissitzky Letters and Photographs, 1911-1941

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf6r29n84d No online items Finding aid for the El Lissitzky letters and photographs, 1911-1941 Finding aid prepared by Carl Wuellner. Finding aid for the El Lissitzky 950076 1 letters and photographs, 1911-1941 ... Descriptive Summary Title: El Lissitzky letters and photographs Date (inclusive): 1911-1941 Number: 950076 Creator/Collector: Lissitzky, El, 1890-1941 Physical Description: 1.0 linear feet(3 boxes) Repository: The Getty Research Institute Special Collections 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 1100 Los Angeles, California, 90049-1688 (310) 440-7390 Abstract: The El Lissitzky letters and photographs collection consists of 106 letters sent, most by Lissitzky to his wife, Sophie Lissitzky-Küppers, along with his personal notes on art and aesthetics, a few official and personal documents, and approximately 165 documentary photographs and printed reproductions of his art and architectural designs, and in particular, his exhibition designs. Request Materials: Request access to the physical materials described in this inventory through the catalog record for this collection. Click here for the access policy . Language: Collection material is in German Biographical/Historial Note El Lissitzky (1890-1941) began his artistic education in 1909, when he traveled to Germany to study architecture at the Technische Hochschule in Darmstadt. Lissitzky returned to Russia in 1914, continuing his studies in Moscow where he attended the Riga Polytechnical Institute. After the Revolution, Lissitzky became very active in Jewish cultural activities, creating a series of inventive illustrations for books with Jewish themes. These formed some of his earliest experiments in typography, a key area of artistic activity that would occupy him for the remainder of his life. -

The Russian Avant-Garde 1912-1930" Has Been Directedby Magdalenadabrowski, Curatorial Assistant in the Departmentof Drawings

Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art leV'' ST,?' T Chairm<ln ,he Boord;Ga,dner Cowles ViceChairman;David Rockefeller,Vice Chairman;Mrs. John D, Rockefeller3rd, President;Mrs. Bliss 'Ce!e,Slder";''i ITTT V P NealJ Farrel1Tfeasure Mrs. DouglasAuchincloss, Edward $''""'S-'ev C Burdl Tn ! u o J M ArmandP Bar,osGordonBunshaft Shi,| C. Burden,William A. M. Burden,Thomas S. Carroll,Frank T. Cary,Ivan Chermayeff, ai WniinT S S '* Gianlui Gabeltl,Paul Gottlieb, George Heard Hdmilton, Wal.aceK. Harrison, Mrs.Walter Hochschild,» Mrs. John R. Jakobson PhilipJohnson mM'S FrankY Larkin,Ronalds. Lauder,John L. Loeb,Ranald H. Macdanald,*Dondd B. Marron,Mrs. G. MaccullochMiller/ J. Irwin Miller/ S.I. Newhouse,Jr., RichardE Oldenburg,John ParkinsonIII, PeterG. Peterson,Gifford Phillips, Nelson A. Rockefeller* Mrs.Albrecht Saalfield, Mrs. Wolfgang Schoenborn/ MartinE. Segal,Mrs Bertram Smith,James Thrall Soby/ Mrs.Alfred R. Stern,Mrs. Donald B. Straus,Walter N um'dWard'9'* WhlTlWheeler/ Johni hTO Hay Whitney*u M M Warbur Mrs CliftonR. Wharton,Jr., Monroe * HonoraryTrustee Ex Officio 0'0'he "ri$°n' Ctty ot^New^or^ °' ' ^ °' "** H< J Goldin Comptrollerat the Copyright© 1978 by TheMuseum of ModernArt All rightsreserved ISBN0-87070-545-8 TheMuseum of ModernArt 11West 53 Street,New York, N.Y 10019 Printedin the UnitedStates of America Foreword Asa resultof the pioneeringinterest of its first Director,Alfred H. Barr,Jr., TheMuseum of ModernArt acquireda substantialand uniquecollection of paintings,sculpture, drawings,and printsthat illustratecrucial points in the Russianartistic evolution during the secondand third decadesof this century.These holdings have been considerably augmentedduring the pastfew years,most recently by TheLauder Foundation's gift of two watercolorsby VladimirTatlin, the only examplesof his work held in a public collectionin the West. -

Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984)

1 de 2 SCULPTOR NINA SLOBODINSKAYA (1898-1984). LIFE AND SEARCH OF CREATIVE BOUNDARIES IN THE SOVIET EPOCH Anastasia GNEZDILOVA Dipòsit legal: Gi. 2081-2016 http://hdl.handle.net/10803/334701 http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/deed.ca Aquesta obra està subjecta a una llicència Creative Commons Reconeixement Esta obra está bajo una licencia Creative Commons Reconocimiento This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution licence TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898 -1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 TESI DOCTORAL Sculptor Nina Slobodinskaya (1898-1984) Life and Search of Creative Boundaries in the Soviet Epoch Anastasia Gnezdilova 2015 Programa de doctorat: Ciències humanes I de la cultura Dirigida per: Dra. Maria-Josep Balsach i Peig Memòria presentada per optar al títol de doctora per la Universitat de Girona 1 2 Acknowledgments First of all I would like to thank my scientific tutor Maria-Josep Balsach I Peig, who inspired and encouraged me to work on subject which truly interested me, but I did not dare considering to work on it, although it was most actual, despite all seeming difficulties. Her invaluable support and wise and unfailing guiadance throughthout all work periods were crucial as returned hope and belief in proper forces in moments of despair and finally to bring my study to a conclusion. My research would not be realized without constant sacrifices, enormous patience, encouragement and understanding, moral support, good advices, and faith in me of all my family: my husband Daniel, my parents Andrey and Tamara, my ount Liubov, my children Iaroslav and Maria, my parents-in-law Francesc and Maria –Antonia, and my sister-in-law Silvia. -

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937

"The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937 The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Johnson, Samuel. 2015. "The Architecture of the Book": El Lissitzky's Works on Paper, 1919-1937. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:17463124 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 A dissertation presented by Samuel Johnson to The Department of History of Art and Architecture in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History of Art and Architecture Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts May 2015 © 2015 Samuel Johnson All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Maria Gough Samuel Johnson “The Architecture of the Book”: El Lissitzky’s Works on Paper, 1919-1937 Abstract Although widely respected as an abstract painter, the Russian Jewish artist and architect El Lissitzky produced more works on paper than in any other medium during his twenty year career. Both a highly competent lithographer and a pioneer in the application of modernist principles to letterpress typography, Lissitzky advocated for works of art issued in “thousands of identical originals” even before the avant-garde embraced photography and film. -

Exhibition Provides New Insight Into the Globalization of Conceptual Art, Through Work of Nearly 50 Moscow-Based Artists Thinki

EXHIBITION PROVIDES NEW INSIGHT INTO THE GLOBALIZATION OF CONCEPTUAL ART, THROUGH WORK OF NEARLY 50 MOSCOW-BASED ARTISTS THINKING PICTURES FEATURES APPROXIMATELY 80 WORKS, INCLUDING MAJOR INSTALLATIONS, WORKS ON PAPER, PAINTINGS, MIXED-MEDIA WORKS, AND DOCUMENTARY MATERIALS, MANY OF WHICH OF HAVE NOT BEEN PUBLICLY DISPLAYED IN THE U.S. New Brunswick, NJ—February 23, 2016—Through the work of nearly 50 artists, the upcoming exhibition Thinking Pictures will introduce audiences to the development and evolution of conceptual art in Moscow—challenging notions of the movement as solely a reflection of its Western namesake. Opening at the Zimmerli Art Museum at Rutgers in September 2016, the exhibition will explore the unique social, political, and artistic conditions that inspired and distinguished the work of Muscovite artists from peers working in the U.S. and Western Europe. Under constant threat of censorship, and frequently engaging in critical opposition to Soviet-mandated Socialist Realism, these artists created works that defied classification, interweaving painting and installation, parody and performance, and images and texts in new types of conceptual art practices. Drawn from the Norton and Nancy Dodge Collection at the Zimmerli, the exhibition features masterworks by such renowned artists as Ilya Kabakov, Komar and Melamid, Eric Bulatov, Andrei Monastyrsky, and Irina Nakhova, and introduces important works by under-represented artists, including Yuri Albert, Nikita Alekseev, Ivan Chuikov, Elena Elagina, Igor Makarevich, Viktor Pivovarov, Oleg Vassiliev, and Vadim Zakharov. Many of the works in the exhibition have never been publicly shown in the U.S., and many others only in limited engagement. Together, these works, created in a wide-range of media, underscore the diversity and richness of the underground artistic currents that comprise ‘Moscow Conceptualism’, and provide a deeper and more global understanding of conceptual art, and its relationship to world events and circumstances. -

The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory

The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory Elmedin Žunić ORCID ID: 0000-0003-3694-7098 Submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Melbourne Faculty of Fine Arts and Music July 2018 Abstract The Bosnian Case: Art, History and Memory concerns the representation of historic and traumatogenic events in art through the specific case of the war in Bosnia 1992-1995. The research investigates an aftermath articulated through the Freudian concept of Nachträglichkeit, rebounding on the nature of representation in the art as always in the space of an "afterness". The ability to represent an originary traumatic scenario has been questioned in the theoretics surrounding this concept. Through The Bosnian Case and its art historical precedents, the research challenges this line of thinking, identifying, including through fieldwork in Bosnia in 2016, the continuation of the war in a war of images. iii Declaration This is to certify that: This dissertation comprises only my original work towards the PhD except where indicated. Due acknowledgement has been made in the text to all other material used. This dissertation is approximately 40,000 words in length, exclusive of figures, references and appendices. Signature: Elmedin Žunić, July 2018 iv Acknowledgements First and foremost, my sincere thanks to my supervisors Dr Bernhard Sachs and Ms Lou Hubbard. I thank them for their guidance and immense patience over the past four years. I also extend my sincere gratitude to Professor Barbara Bolt for her insightful comments and trust. I thank my fellow candidates and staff at VCA for stimulating discussions and support. -

Detki V Kletke: the Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry

Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Morse, Ainsley. 2016. Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children's Literature and Unofficial Poetry. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University, Graduate School of Arts & Sciences. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:33493521 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry A dissertation presented by Ainsley Elizabeth Morse to The Department of Slavic Languages and Literatures in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of Slavic Languages and Literatures Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts April 2016 © 2016 – Ainsley Elizabeth Morse. All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Stephanie Sandler Ainsley Elizabeth Morse Detki v kletke: The Childlike Aesthetic in Soviet Children’s Literature and Unofficial Poetry Abstract Since its inception in 1918, Soviet children’s literature was acclaimed as innovative and exciting, often in contrast to other official Soviet literary production. Indeed, avant-garde artists worked in this genre for the entire Soviet period, although they had fallen out of official favor by the 1930s. This dissertation explores the relationship between the childlike aesthetic as expressed in Soviet children’s literature, the early Russian avant-garde and later post-war unofficial poetry. -

Garage Museum of Contemporary Art Presents: Kholin and Sapgir

GARAGE MUSEUM OF CONTEMPORARY ART PRESENTS: KHOLIN AND SAPGIR. MANUSCRIPTS May 20–August 13, 2017 Free Admission This summer, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art presents an exhibition of documents relating to the poetry of Igor Kholin (1920–1999) and Genrikh Sapgir (1928–1999), offering fresh insight into the work of two pioneers of Soviet nonconformist literature. Their names are often encountered together: in literary analysis, in publications on Russian contemporary art, and on children’s book shelves. Kholin and Sapgir met in 1952 and became close allies. Both were members of the first postwar unofficial community of artists and poets, known as the Lianozovo group, and pupils of its leader, artist Evgeny Kropivnitsky. They worked alongside some of the key names in Russian postwar art, including Oskar Rabin, Lydia Masterkova, and Vladimir Nemukhin. Bohemians of the 1960s and 1970s, their avant-garde poetry was unpublishable until the advent of perestroika. They were heroes of the literary underground, pioneers of samizdat, and featured in the first issue of the samizdat poetry journal Sintaksis, published by Alexander Ginsburg in 1959. Both combined an innovative style of writing with a strong commitment to truth, and a genuine interest in the life of ordinary people. They fused expressionism and realism, with an acute sense of the tragedy of the everyday and the poetics of the absurd. Their funny and moving “barracks poetry” quickly became part of Soviet folklore, often quoted by people who had never read the original texts. Kholin and Sapgir led a double life typical of nonconformist writers and artists of the post-Stalin era: showing their work only to a small audience of friends and admirers, they took odd jobs to make a living. -

INSTRUMENTS for NEW MUSIC Luminos Is the Open Access Monograph Publishing Program from UC Press

SOUND, TECHNOLOGY, AND MODERNISM TECHNOLOGY, SOUND, THOMAS PATTESON THOMAS FOR NEW MUSIC NEW FOR INSTRUMENTS INSTRUMENTS PATTESON | INSTRUMENTS FOR NEW MUSIC Luminos is the open access monograph publishing program from UC Press. Luminos provides a framework for preserv- ing and reinvigorating monograph publishing for the future and increases the reach and visibility of important scholarly work. Titles published in the UC Press Luminos model are published with the same high standards for selection, peer review, production, and marketing as those in our traditional program. www.luminosoa.org The publisher gratefully acknowledges the generous contribu- tion to this book provided by the AMS 75 PAYS Endowment of the American Musicological Society, funded in part by the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation. The publisher also gratefully acknowledges the generous contribution to this book provided by the Curtis Institute of Music, which is committed to supporting its faculty in pursuit of scholarship. Instruments for New Music Instruments for New Music Sound, Technology, and Modernism Thomas Patteson UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA PRESS University of California Press, one of the most distin- guished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activi- ties are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institu- tions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu. University of California Press Oakland, California © 2016 by Thomas Patteson This work is licensed under a Creative Commons CC BY- NC-SA license. To view a copy of the license, visit http:// creativecommons.org/licenses. -

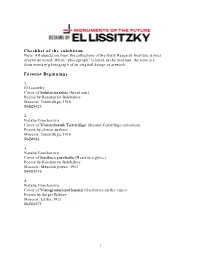

Checklist of the Exhibition Checklist of the Exhibition Note: All Objects Are

Checklist of the exhibition Note: All objects are from the collections of the Getty Research Institute, unless otherwise noted. When “photograph” is listed as the medium, the item is a documentary photograph of an original design or artwork. Futurist Beginnings 1. El Lissitzky Cover of Solntse na izlete (Spent sun) Poems by Konstantin Bolshakov Moscow: Tsentrifuga, 1916 88-B24323 2. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Vtoroi sbornik Tsentrifugi (Second Centrifuge collection) Poems by eleven authors Moscow: Tsentrifuga, 1916 90-B4642 3. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Serdtse v perchatke (Heart in a glove) Poems by Konstantin Bolshakov Moscow: Mezonin poezii, 1913 88-B24316 4. Natalia Goncharova Cover of Vetrogradari nad lozami (Gardeners on the vines) Poems by Sergei Bobrov Moscow: Lirika, 1913 88-B24275 1 4a. Natalia Goncharova Pages from Vetrogradari nad lozami (Gardeners on the vines) Poems by Sergei Bobrov Moscow: Lirika, 1913 88-B24275 Yiddish Book Design 5. El Lissitzky Dust jacket from Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 6a. El Lissitzky Cover of Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 6b. El Lissitzky Page from Had gadya (One goat) Children’s illustrated book based on the Jewish Passover song Kiev: Kultur Lige, 1919 1392-150 7. El Lissitzky Cover of Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An everyday conversation: A story) Tale by Moses Broderson Moscow: Ferlag Chaver, 1917 93-B15342 8. El Lissitzky Frontispiece from deluxe edition of Sihas hulin: Eyne fun di geshikhten (An everyday conversation: A story) Tale by Moses Broderson Moscow: Shamir, 1917 93-B15342 2 9. -

IRINA KORINA: “I Am Interested in How to Make Work That Joins Memories, Nostalgia, and Architecture

SUMMER 2017 EXHIBITION SEASON IRINA KORINA: “I am interested in how to make work that joins memories, nostalgia, and architecture. For me, ultimately, Congo Art Works: it’s about a Popular Painting transformation /PAGE 4 of the hierarchy Raymond Pettibon. The Cloud of of values.” Misreading /PAGE 6 David Adjaye: Form, Heft, Material /PAGE 12 Kholin and Sapgir. Manuscripts /PAGE 14 Bone Music. An Interview with Stephen Coates /PAGE 15 Irina Korina: The Tail Wags the Comet /PAGE 3 www.garagemca.org 2 EDITORIAL Welcome! Dear Garage visitor, Dasha Zhukova, Anton Belov, Founder, Garage Museum Director, Garage Museum of Contemporary Art of Contemporary Art his is the third edition of Garage Gazette, an hether you are at Garage for the first time to the collector and chronicler of Moscow underground annual publication which provides information or a regular visitor, I’d like to welcome art Leonid Talochkin and the artist Viktor Pivovarov. The about the Museum’s summer season and gives you to the Museum, which has become an Archive is accessible to the general public—we even offer a sneak preview of what’s to come in fall. First, established landmark in Gorky Park since free tours—and we continue to curate exhibitions based Tthough, I would like to look back to the start of 2017 Wopening here two years ago. We are really excited about on our holdings. This summer you can see Kholin and and Garage Triennial of Russian Contemporary Art, our summer season and hope that you will be too. Sapgir. Manuscripts, which looks at the work of two lead- which brought together works by over 60 artists and Since March, we have presented a specially-commis- ing poets of the Moscow underground with strong links to artist groups from across the country. -

El Lissitzky – Jewish As Universal: from Jewish Style to Pangeometry Style Jewish from As Universal: – Jewish El Lissitzky Fig

El Lissitzky – Jewish as Universal: From Jewish Style to Pangeometry Igor Dukhan “Avant-garde oeuvre” implies certain dualities. On the one metaphorical textures are constructed and designed. To hand, it attempts to present a new vision of the totality put it differently, the strongest rationalistic will towards of the world, a rational proposal for the “reconstruction synthesis moves Lissitzky beyond rationality, just as the of the world.” On the other hand, it might imply refined Jewishness of his “Jewish-style” works contains formative symbolist play, full of direct, and especially hidden, impulses of universality. From yet another viewpoint, his references and quotations. Furthermore, the avant-garde abstract suprematist and post-suprematist creations and oeuvre is intended to speak universally; yet, it contains theories imply a hidden, genuine Jewishness. diverse national, nationalistic, and even chauvinistic Despite the artist’s own theories about his works, traits (the latter flourished during and immediately after despite a perfect intellectual biography of Lissitzky written World War I), which internally contradict its universalism by his wife and the recollections of his contemporaries,3 from within. Lissitzky’s ecstatic evolution and balance between With regard to formative avant-garde dualities, El artistic trends and national traditions create problems for Lissitzky is a characteristic case. The “enigmatic artist” of researchers. The artist’s passage from Darmstadt, where he the avant-garde epoch,1 he was both Jewish and universal, was trained in late Art Nouveau perspective to pre- and rationally-constructive and symbolically-enigmatic. He post-revolutionary Russia, where he discovered Jewish attempted to be universal while playing with sophisticated tradition and searched for Jewish style, followed by the and hidden Jewish metaphors.