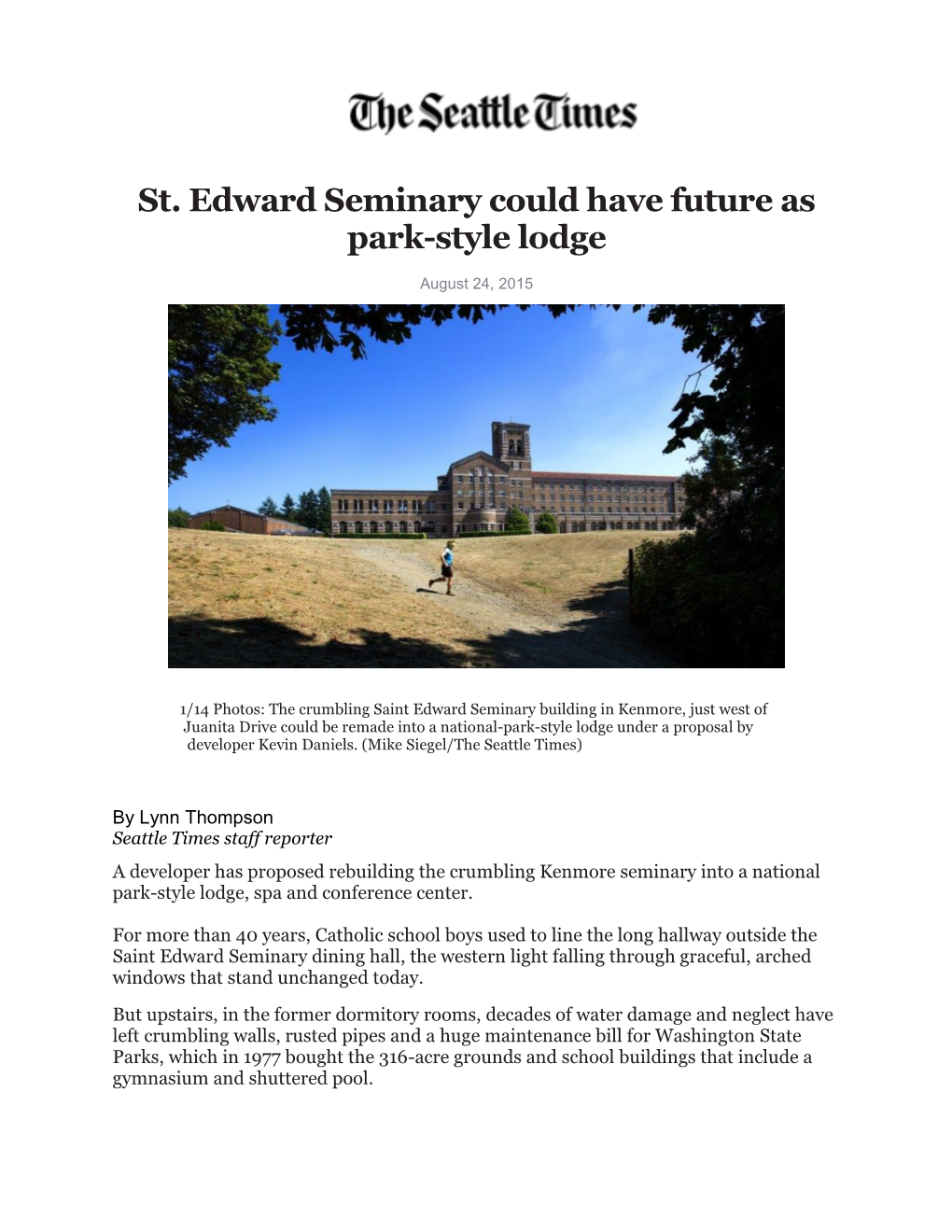

A Developer Has Proposed Rebuilding the Crumbling Kenmore Seminary Into a National Park-Style Lodge, Spa and Conference Center

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hello, I Am Writing As a Concerned Citizen Regarding St Edwards Park

SAINT EDWARD SEMINARY LEASE COMMENTS DECEMBER 2016 Hello, I am writing as a concerned citizen regarding St Edwards Park and the potential for the renovation of turning it into a lodge. I wanted to put my two cents in and let you know that it is very important for there to be plenty of parking for non-hotel visitors and am requesting for an underground parking structure to be required. Even thought I am not for this renovation as I am very concerned for the wild-life. The noise, the visitors, the construction, the constant light pollution...I am sure all this new activity will affect all living things nearby, where will they go? Having grown up in Washington, and have lived here since the 70's, I have witnessed so much forest being cut down for us humans. There is not much left. St Edwards is such a special place to visit, so special that I would give up my rights to be there so as to make it a sanctuary for wildlife and not disturb them. However, having said my peace, if there is to be a 'lodge', I do request a parking structure to make room for us visitors who like to take quiet walks in the forest. Washington State Park Officials: Please approve the Kevin Daniels' Firm's proposal to restore the historical and architecturally significant Seminary Building in St. Edwards Park. This proposal provides the funds to restore this beautiful building to its former glory and an economically sustainable future that park visitors can use, enjoy, and be proud of for years to come. -

Saint Edward Seminary Preliminary Staff Finding on Commerce Study - Requested Action

Item E-X: Saint Edward Seminary Preliminary Staff Finding on Commerce Study - Requested Action EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This item asks the Commission to determine whether there is a viable public or nonprofit use of the Saint Edward Seminary based on criteria established in Engrossed Second Substitute House Bill 2667, passed by the 2016 Washington State Legislature. This item supports the Strategic Plan goal to develop amenities that advance transformation by leveraging partner-funded park development projects. INTRODUCTION: In spring 2016, legislation was signed by the Governor that required actions by the State Parks and Recreation Commission and the Department of Commerce regarding the Saint Edward Seminary. Engrossed Second Substitute House Bill 2667 (ESSHB2667) directed Commerce to conduct an economic viability study and directed the Commission to affirmatively make a determination based on that study and other Commission-criteria on the viability of a public or non-profit use of the Seminary property. As directed in the bill, State Parks staff consulted with Commerce and provided them with existing background data on the Seminary including various historic studies, cost estimates, and proposals that could be incorporated into the study. This agenda item provides State Park staff analysis and recommendations of the following: · Requirements of ESSHB2667 · Background information on the multi-decades search for preservation and re-use of the Saint Edward Seminary property · Interpretation of the Commerce study · Analysis of Public and Non-Profit Options in light of evaluation criteria in ESSHB2667 · Staff recommendations for a Commission finding pursuant to ESSHB2667 Requirements of Engrossed Second Substitute House Bill 2667 ESSHB2667, passed by the 2016 Session of the Washington State Legislature and codified as RCW79A.05.025(2), provides an opportunity for the Commission to enter into a lease of the Seminary grounds of up to 62 years. -

City of Kenmore Receives Help Preserving Saint Edward Seminary

City of Kenmore receives help preserving Saint Edward Seminary Aug 1, 2014 The city of Kenmore is working with Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission and Daniels Real Estate to preserve, rehabilitate and activate the former Saint Edward Seminary building. — image credit: Sarah Kehoe, Bothell Reporter The city of Kenmore is working with Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission and Daniels Real Estate to preserve, rehabilitate and activate the former Saint Edward Seminary building. The state parks commission discussed the project with city representatives at a July 23 work session in Bellingham. The iconic building, which is on the National Register of Historic Places, is located at Saint Edward State Park in Kenmore and has been largely vacant since 1976. “Saving the historic seminary building in a way that promotes sustainability and environmental values, while enhancing the local economy, is a huge opportunity for the city, and we are ready to be a helpful partner in this effort,” Kenmore Mayor David Baker said. “The team that has stepped forward is truly high caliber with strong community ties, as well as national prominence.” In response to the Washington State Parks Commission’s Resolution in 2013, which directed state parks staff to explore partnerships with other public and private sector entities to rehabilitate and preserve the building, the city of Kenmore is proposing to play an active role with state parks to ensure a long-term lease to rehabilitate and reuse the building. This could include the formation of a Public Development Authority. A similar agreement was formed in 2013 when the Washington State Parks Commission approved a lease with a Public Development Authority chartered by the city of Port Townsend for a portion of Fort Worden State Park in Jefferson County. -

Letters to State Parks Regarding the Seminary September 3, 2011 1

Letters to State Parks Regarding the Seminary September 3, 2011 Note: names, outside of public officials, have been removed for privacy. First things first: * I support extending the one-year extension for consideration of rehab proposals for the seminary at St. Edward State Park. * If a citizens advisory committee is formed, I volunteer to be a member…”qualifications” below. I attended the public meeting held in Kenmore on August 25. A decade ago, when McMenamins submitted their proposal, I attended those meetings in support of it. I learned soooo much about the seminary (the park staff gave tours at the time), both from a building perspective, i.e., internal storm water collection system, and the people’s stories that went with it. A brother-in-law even attended school/seminary there. Mostly, I heard a vocal unreasonable opposition to the plan. A lawyer/bicyclist who was part of that group (and who was citing RCWs at the recent meeting) was particularly aggressive. In fact, I made my way to Normandy Park one snowy day for a commission hearing and he was there; he had the audacity to say to me, “I can’t believe you are still coming to these meetings,” suggesting, I suppose, that my support for the McMenamins was a lost cause. I believe the citizens of Kenmore woke up and realized what a gem they lost (thanks, in part, to the McMenamins construction in nearby Bothell) and turned out in force on August 25th to support the most recent turn of events. I was thrilled! And Daniels Real Estate appears to be just the right developer to take on this project in the vacuum left by the McMenamin brothers. -

New Hotel Breaks Ground in Kenmore's Saint Edward Park

New hotel breaks ground in Kenmore’s Saint Edward Park The old seminary building in the park will be preserved and turned into a lodge, opening in 2020. By Katie Metzger, December 12, 2018 To mark a milestone in its restoration and renovation of the seminary building at Saint Edward State Park in Kenmore, Daniels Real Estate LLC held a ceremonial groundbreaking near the site on Dec. 7. Washington State Parks and Recreation commissioners were in attendance, as well as local elected officials and project partners, from Bastyr University and the Washington Trust for Historic Preservation to the city of Kenmore and the Bothell Kenmore Chamber of Commerce. Ken Bounds, chair of the State Parks commission, and Kevin Daniels, president of Daniels Real Estate, acknowledged the many years of work and advocacy that led to the day’s celebration. Daniels had to work on many levels, from neighborhood meetings to hearings in Olympia, on his plan to turn the seminary building into a hotel and spa while maintaining its historic character. “It wasn’t a simple journey, and it wasn’t an easy task,” Daniels said. “You may not realize how tough this was from the beginning, because it’s a new idea to do something in the middle of a state park.” Bounds noted that the seminary building was “literally falling apart” and “being terribly underutilized,” and State Parks had to make a choice about what to do with it. The agency is responsible for more than 700 historic structures, but is operating with less general fund revenue than it used to. -

City Council Regular Meeting Agenda 7:00 P.M., Monday, September 26, 2016 Kenmore City Hall, Council Chambers 18120 68Th Ave

City of Kenmore City of Kenmore - 18120 68th Avenue NE - P.O. Box 82607 - Kenmore, WA 98028 Phone: 425-398-8900 - Fax: 425-481-3236 - E-mail: [email protected] City of Kenmore City Council Regular Meeting Agenda 7:00 p.m., Monday, September 26, 2016 Kenmore City Hall, Council Chambers 18120 68th Ave. NE, Kenmore, WA 98028 If you have any questions or to confirm agenda items prior to the meeting, or if you require special accommodations, please call the City Clerk at 425-398-8900. You may also stop by City Hall at 18120 68th Avenue NE, Kenmore. Council agendas are also available on our website at www.kenmorewa.gov. I. CALL MEETING TO ORDER II. ROLL CALL III. FLAG SALUTE IV. AGENDA APPROVAL V. PRESENTATION A. Recognition of 10 Years of Service to the City - Andrew Bauer Certificate VI. PROCLAMATION A. Domestic Violence Awareness Month - October 2016 Proclamation VII. CITIZEN COMMENTS A. This is an opportunity to express your views on issues that are important to you and to the community. Please limit your comments to three (3) minutes. VIII. CONSENT AGENDA A. The following checks and electronic payments are approved for payment: Total Check Numbers 35165 through 35251 in the amount of $737,608.19 Total Payroll Electronic Deposits Dated 09/02/2016 in the amount of $80,371.92 Checks & Electronic Payments City of Kenmore - City Council Meeting Agenda for September 26, 2016 Page 2 of 69 B. Contract No. 14-C1322 Amendment No. 2, Corey Hansen, Business Incubator Consultant Agenda Bill & Attachments IX. BUSINESS AGENDA A. -

E Mass of Reception of the Most Reverend Paul D

e Mass of Reception of the Most Reverend Paul D. Etienne as Coadjutor Archbishop of Seattle The Most Reverend J. Peter Sartain Archbishop of Seattle Presider St. James Cathedral, Seattle 7 June 2019 2:00pm His Holiness Pope Francis e Most Reverend Christophe Pierre Apostolic Nuncio to the United States of America e Most Reverend J. Peter Sartain Archbishop of Seattle The Most Reverend Paul D. Etienne Coadjutor Archbishop of Seattle Archbishop Etienne’s Motto comes from the Letter of St. Paul to the Ephesians 4:15: “Rather, living the truth in love, we should grow in every way into him who is the head, Christ.” As Church, we believe Christ is the ultimate expression of truth as well as the ultimate expression and experience of love. As one sent by Christ, I ask for his blessing as we begin this next chapter of faith together. When Christ sent his first disciples, he told them to take nothing with them for the journey. This was because he was to be their sole possession. May we rely only and always upon Christ. Archbishop Etienne's Coat of Arms: The exterior is the traditional “framing” of a bishop’s coat of arms. An archbishop’s arms have 10 tassels on each side to represent his office. The sword represents St. Paul, Archbishop Etienne’s patron, and the book represents the Sacred Scriptures and preaching. The M is for Archbishop Etienne’s devotion to the Blessed Mother. The Sun (star) symbolizes Christ, the Dawn from on High, as well as Archbishop Etienne’s general love of the outdoors. -

Summary of Saint Edward State Park's

NFS Form 10-900a OMBNo. 1024-0018 (1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section Page SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 07000137 Date Listed: 3/8/2007 Saint Edward Seminary WA Property Name State N/A Multiple Name This property is listed in the National Register of Historic Places in accordance with the attached nomination documentation subject to the following exceptions, exclusions, or amendments, notwithstanding the National Park Service certification included in the nomination documentation. • 7 Sigrlatur^e 6f the Keeper Date of Action Amendeor Items in Nomination: Significance: Criteria Consideration G (Properties That Have Achieved Significance Within the Last Fifty Years) does not have to be checked or justified for a property whose period of significance overlaps the 50 year period by only a single year, as long as the period itself is sufficiently justified. Criteria Consideration A (Religious Properties) does need to be checked and justified for a resource constructed and owned historically by a religious institution and used for religious purposes. The St. Edward Seminary appears to meet Criteria Consideration A as a property significant for its architectural distinction, as a property significant under the theme of education, and as a property significant under the theme of religion having secular scholarly recognition for its broad impact on the history of the local area. [Criteria Consideration A is added.] These clarifications were confirmed with the WA SHPO office DISTRIBUTION: National Register property file Nominating Authority (without nomination attachment) NFS Form 10-900a OMBNo. 1024-0018 (1-31-2009) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES CONTINUATION SHEET Section ___ Page _ SUPPLEMENTARY LISTING RECORD NRIS Reference Number: 07000137 Date Listed: 3/8/2007 Saint Edward Seminary King WA Property Name County State (Continued) Geographical Data: The U. -

St. Edward Seminary Historic Structure Report

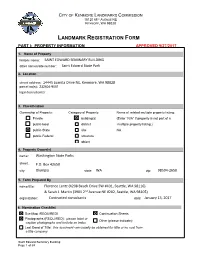

CITY OF KENMORE LANDMARKS COMMISSION 18120 68TH AVENUE NE KENMORE, WA 98028 LANDMARK REGISTRATION FORM PART I: PROPERTY INFORMATION APPROVED 9/27/2017 1. Name of Property historic name: SAINT EDWARD SEMINARY BUILDING other names/site number: Saint Edward State Park 2. Location street address: 14445 Juanita Drive NE, Kenmore, WA 98028 parcel no(s): 232604-9001 legal description(s): 3. Classification Ownership of Property: Category of Property: Name of related multiple property listing: Private building(s) (Enter “N/A” if property is not part of a public-local district multiple property listing.) public-State site NA public-Federal structure object 4. Property Owner(s) name: Washington State Parks street: P.O. Box 42650 city: Olympia state: WA zip: 98504-2650 5. Form Prepared By name/title: Florence Lentz (4208 Beach Drive SW #401, Seattle, WA 98116) & Sarah J. Martin (3901 2nd Avenue NE #202, Seattle, WA 98105) organization: Contracted consultants date: January 13, 2017 6. Nomination Checklist Site Map (REQUIRED) Continuation Sheets Photographs (REQUIRED): please label or Other (please indicate): caption photographs and include an index Last Deed of Title: this document can usually be obtained for little or no cost from a title company Saint Edward Seminary Building Page 1 of 69 PART II: PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION 7.fjjdlfklsjdflkjdsfj Alterations Check the appropriate box if there have been changes to plan, cladding, windows, interior features or other significant elements. These changes should be described specifically in the narrative section below. Yes No Plan (i.e. no additions to footprint, Yes No Interior features (woodwork, relocation of walls, or roof plan) finishes, flooring, fixtures) Yes No Cladding Yes No Other elements Yes No Windows Narrative Description Use the space below to describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance, condition, architectural characteristics, and the above-noted alterations (use continuation sheet if necessary). -

Saint Edward Seminary Lease - Requested Action

Don Hoch Director STATE OF WASHINGTON WASHINGTON STATE PARKS AND RECREATION COMMISSION 1111 Israel Road S.W. P.O. Box 42650 Olympia, WA 98504-2650 (360) 902-8500 TDD (Telecommunications Device for the Deaf): (800) 833-6388 www.parks.wa.gov January 9, 2017 Item E-1: Saint Edward Seminary Lease - Requested Action EXECUTIVE SUMMARY: This item asks the Washington State Parks and Recreation Commission to approve an exchange of land to State Parks of a parcel known as the McDonald property in return for a conveyance of a 62-year lease to the Daniels Group for a 5.5-acre tract of land, including the Seminary building and associated structures, at Saint Edward State Park and to delegate authority to the Director to execute the exchange agreement and lease. This item aligns with agency core values and advances the Commission’s strategic goal: “Demonstrate that all Washingtonians benefit from their state parks.” SIGNIFICANT BACKGROUND INFORMATION: Saint Edward State Park, located in the City of Kenmore, is 316 acres and includes 3,000 feet of freshwater shoreline on Lake Washington. The property is characterized by second growth forest, Lake Washington shoreline, wide-open expanses of lawns and sports fields, and the Seminary building complex. The park was acquired by the State of Washington from the Archdiocese of Seattle in 1977 for $7,000,000. Since the property acquisition, the Dining Hall of the Seminary has been rented for special events and classes and the upper floors formerly used as staff housing. The building served as a Catholic Seminary for young men from 1931 to 1976. -

Geotechnical Report Geotechnical Recommendations & Geologically Hazardous Areas Assessment

GEOTECHNICAL REPORT GEOTECHNICAL RECOMMENDATIONS & GEOLOGICALLY HAZARDOUS AREAS ASSESSMENT Proposed Parking Garage and Surface Parking Saint Edward Seminary Kenmore, Washington PROJECT NO. 16-163 June 2016 Prepared for: Daniels Real Estate Geotechnical & Earthquake Engineering Consultants Geotechnical & Earthquake Engineering Consultants June 29, 2016 PanGEO Project No. 16-163 Ms. Trevina Wang Daniels Real Estate 2401 Utah Avenue South, Suite 305 Seattle, WA 98134 Subject: GEOTECHNICAL REPORT GEOTECHNICAL RECOMMENDATIONS & GEOLOGICALLY HAZARDOUS AREAS ASSESSMENT Proposed Parking Garage and Surface Parking Saint Edward Seminary 14445 Juanita Drive NE, Kenmore, Washington Dear Ms. Wang: As requested, PanGEO, Inc. is pleased to present the attached report to assist the project team with the design and construction of the proposed parking garage and surface parking adjacent to the Saint Edward Seminary in Kenmore, Washington. In preparing this report, we completed 11 test borings to evaluate the subsurface conditions, conducted a reconnaissance of the geologic hazards at the site, conducted laboratory testing, performed our engineering analysis, and prepared this report. Based the results of our study, the site is underlain by glacially consolidated clay, silt, and silty sand with gravel. In our opinion, the proposed parking garage can be supported on conventional spread footings. Saint Edward Park contains areas mapped by the City of Kenmore as geologic hazard areas due to erosion and landslide hazards. Based on our review of the City’s mapping and a reconnaissance of the study area, it appears the planned improvements are located more than 150 feet from the mapped geologic hazards. As such, in our opinion, provided that the surface water will be properly managed, the potential for the planned improvements to affect these geologically hazardous areas is minimal. -

Lodge at Saint Edward

ADDENDUM to the FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT for the Lodge at Saint Edward Project File No. CSP16-0077 December 2016 prepared by the City of Kenmore Development Services Kenmore, Washington TO: Recipients of the Lodge at Saint Edward FEIS FROM: The City of Kenmore SUBJECT: Lodge at Saint Edward Final EIS Addendum DATE: December 30, 2016 The City of Kenmore is circulating this Addendum to the Lodge at Saint Edward Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) issued on December 16, 2016. This FEIS Addendum is prepared and circulated to present responses to a comment letter on the Draft EIS (DEIS) that was inadvertently omitted from the FEIS1. The City determined that the DEIS and FEIS adequately analyzed the environmental impacts from the project and that the comment letter, and responses to comments, provided in this Addendum do not result in any changes to the information and analysis presented in the DEIS and FEIS. The City of Kenmore has also extended the appeal period for an additional 14 days from the original deadline of January 6, 2017; the appeal period will now end on January 20, 2017 at 4:30 PM. Thank you for your interest in the Lodge at Saint Edward Project. Sincerely, Bryan Hampson Development Services Director City of Kenmore 1 Prepared pursuant to WAC 197-11-625 ADDENDUM to the FINAL ENVIRONMENTAL IMPACT STATEMENT for the Lodge at Saint Edward Project File No. CSP16-0077 This Final Environmental Impact Statement Addendum (FEIS Addendum) for the Lodge at Saint Edward has been prepared in compliance with the State Environmental Policy Act (SEPA) of 1971 (Chapter 43.21C, Revised Code of Washington); the SEPA Rules, effective April 4, 1984, as amended (Chapter 197-11, Washington Administrative Code); and rules adopted by the City of Kenmore implementing SEPA – the Environmental Procedures Code (Chapter 19.35, Kenmore Municipal Code).