The Story of Tripura (1946-1971)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Best Practices 2015-16

AQAR- 2015-2016 BEST PRACTICES Practice I: 1. Title of the Practice: To generate atmosphere for Research and Development 2. Goal: The main objective of this best practice is to generate a research environment inside the college campus. All the young faculty members are motivated by senior teachers as well as also by the authority to get involved with research related activities. 3. Context: In spite of different obstructions there is a healthy competitive environment among the teachers of Women’s college. As a result seminar, work shop is being regularly organized. Faculty members of various departments are also keen to publish their research works in various national/international journals as well as books from various leading publication Houses. Moreover, teachers are engaged in minor research projects funded by UGC. 4. The Practice: i) Senior teachers and authority motivate young teachers to approach to various funding agencies for major and minor research proposals as well as also for seminar/workshops. ii) All faculties are always interested in surfing different journals through Google, archive and INFLIBNET regularly. iii) There is a constant thrust to improve the arena of knowledge and to widen the ideas through the mode of interactions among eminent researchers, experts in pioneering research fields during workshops and special lecture sessions. 5. Evidences of Success: In the last one year, faculty members of this college worked hard to create opportunity to carry out research works. The faculty members of Science and Arts departments are pursuing their research activities and published many papers in reputed International and National Journals. Seven books were published with ISBN No. -

Status and Impact of Brick Fields on the River Haora, West Tripura Shreya Bandyopadhyay, Kapil Ghosh, Sushmita Saha, Sumanto Chakravorti and Sunil Kumar De

Trans. Inst. Indian Geographers Status and Impact of Brick Fields on the River Haora, West Tripura Shreya Bandyopadhyay, Kapil Ghosh, Sushmita Saha, Sumanto Chakravorti and Sunil Kumar De. Agartala, Tiripur Abstract The Sadar Subdivision as well as the Haora river Basin is the most economically developed region of West Tripura. Various small scale industries (84 numbers) have grown up in the basin among which brick industry has highest share. Most of the brickields are of recent origin. The SOI Topographical sheet of 1932 (1:63360) and US Army Sheet of 1956 (1:250,000) do not show the existence of any brickield. From Google Map of 2005, several ield visits (since January 2010) and secondary literatures it is found that 62 brick ields are located within the Sadar division of these 57 are located in Haora Basin between Chandrasadhubari at Champaknagar to Jirania towards Agartala. Although brick ields constitute a major part of the industrial activity in Haora Basin area, it adversely affects the portion of river channel as well as its tributaries. Most of the brick ields in the study area were constructed after 1990. Since then the river has been affected by increasing pollution and sedimentation. Dumping of ashes, extraction of sand from the river bed and bank, cutting of tilla lands (approx 15-20 trucks /year/ ield) hinder the natural low of the river. Therefore, the present study has been undertaken to assess the impact of these brick ields in terms of pollution, sedimentation and changing course of the river Haora as well as its tributaries. Key words: Tilla cutting, waste pollutants, sedimentation, changes in river course. -

West Tripura District, Tripura

कᴂद्रीय भूमि जल बो셍ड जल संसाधन, नदी विकास और गंगा संरक्षण विभाग, जल शक्ति मंत्रालय भारत सरकार Central Ground Water Board Department of Water Resources, River Development and Ganga Rejuvenation, Ministry of Jal Shakti Government of India AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT OF GROUND WATER RESOURCES WEST TRIPURA DISTRICT, TRIPURA उत्तर पूिी क्षेत्र, गुिाहाटी North Eastern Region, Guwahati GOVERNMENT OF INDIA MINISTRY OF JAL SHAKTI DEPARTMENT OF WATER RESOURCES, RIVER DEVELOPMENT & GANGA REJUVENATION CENTRAL GROUND WATER BOARD REPORT ON “AQUIFER MAPPING AND MANAGEMENT PLAN OF WEST TRIPURA DISTRICT, TRIPURA” (AAP 2017-18) By Shri Himangshu Kachari Assistant Hydrogeologist Under the supervision of Shri T Chakraborty Officer In Charge, SUO, Shillong & Nodal Officer of NAQUIM, NER CONTENTS Page no. 1. Introduction 1-20 1.1 Objectives 1 1.2 Scope of the study 1 1.2.1 Data compilation & data gap analysis 1 1.2.2 Data Generation 2 1.2.3 Aquifer map preparation 2 1.2.4 Aquifer management plan formulation 2 1.3 Approach and methodology 2 1.4 Area details 2-4 1.5Data availability and data adequacy before conducting aquifer mapping 4-6 1.6 Data gap analysis and data generation 6 1.6.1 Data gap analysis 6 1.6.2 Recommendation on data generation 6 1.7 Rainfall distribution 7 1.8 Physiography 7-8 1.9 Geomorphology 8 1.10 Land use 9-10 1.11Soil 11 1.12 Drainage 11-12 1.13 Agriculture 13-14 1.14 Irrigation 14 1.15 Irrigation projects: Major, Medium and Minor 15-16 1.16 Ponds, tanks and other water conservation structures 16 1.17 Cropping pattern 16-17 1.18 Prevailing water conservation/recharge practices 17 1.19 General geology 18-19 1.20 Sub surface geology 19-20 2. -

Tripura Human Development Report II

Tripura Human Development Report II Pratichi Institute Pratichi (India) Trust 2018 2 GLIMPSES OF THE STUDY Contributory Authors Sabir Ahamed Ratan Ghosh Toa Bagchi Amitava Gupta Indraneel Bhowmik Manabi Majumdar Anirban Chattapadhyay Sangram Mukherjee Joyanta Choudhury Kumar Rana Joyeeta Dey Manabesh Sarkar Arijita Dutta Pia Sen Dilip Ghosh Editors Manabi Majumdar, Sangram Mukherjee, Kumar Rana and Manabesh Sarkar Field Research Sabir Ahamed Mukhlesur Rahaman Gain Toa Bagchi Dilip Ghosh Susmita Bandyopadhyay Sangram Mukherjee Runa Basu Swagata Nandi Subhra Bhattacharjee Piyali Pal Subhra Das Kumar Rana Joyeeta Dey Manabesh Sarkar Tanmoy Dutta Pia Sen Arijita Dutta Photo Courtesy Pratichi Research Team Logistical Support Dinesh Bhat Saumik Mukherjee Piuli Chakraborty Sumanta Paul TRIPURA HUMAN DEVELOPMENT REPORT II 3 4 GLIMPSES OF THE STUDY FOREWORD Amartya Sen India is a country of enormous diversity, and there is a great deal for us to learn from the varying experiences and achievements of the different regions. Tripura’s accomplishments in advancing human development have many distinguishing features which separate it out from much of the rest of India. An understanding of the special successes of Tripura is important for the people of Tripura, but – going beyond that – there are lessons here for the rest of India in appreciating what this small state has been able to achieve, particularly given the adverse circumstances that had to be overcome. Among the adversities that had to be addressed, perhaps the most important is the gigantic influx of refugees into this tiny state at the time of the partition of India in 1947 and again during the turmoil in East Pakistan preceding the formation of Bangladesh in 1971. -

Name of the Post :- District Data Manager (IDSP) Application SL

Following Eligible candidates are requested to attend the competency Assessment Test as mentioned below Name of the Post :- District Data Manager (IDSP) Application SL. No./ Sl No. Name of the Applicant Address Receipt No. S/o:-Lt. Shibcharan Muhuri. Permanent Address, Vill:-West Charakbai. P.O:-Baikhora, 1 1 Sri.Surajit Muhuri. Santirbazar, Pin:-799144, District:- South Tripura , Contact No:- 9774295010 S/o:-Sri.Swadesh Ranjan Saha. Permanent Address Vill:- Jogendranagar, Katashewla, Agartala 2 2 Sri.Sumit Saha . P.O:-Jogendranagar. Pin:- 799004. District:- West Tripura Contact No:-8257074044 S/o: - Sri. Shyamal Ch. Deb Permanent Address, Vill:- West Pratapgarh, Opp . Of Ramthakur 3 3 Sri. Joydeep Deb Palli , Agartala P.O:- A.D. Nagar Pin:-799003 District:- West Tripura , Contact No:- 8258934810/9485158090 D/o:- Lt. Babul Dhar Permanent Address, Vill + P.O:- 4 4 Smt. Bulti Dhar Mashauli Pin: - 799288, District:- Unakoti Tripura Contact No:-9774690468 S/o:- Sri. Gopal Chandra Sarkar. Permanent Address , Vill:-Ramnagar 5 5 Sri. Saurav Sarkar Road No: - 12 , P.O: - Ramnagar Pin:- 799002, District:-West Tripura , Contact No:- 9774889199 S/o:- Sri Ajit Kumar Das Vill:- Murabari , P/o:- Bishalgarh , 6 6 Sri Shantanu Das Sihaijala , Tripura . Pin: - 799102 , Dist:- Siphaijala , Contact No:- 8794680994. Name of the Post :- District Data Manager (IDSP) Application SL. No./ Sl No. Name of the Applicant Address Receipt No. D/o:-Sri. Alakesh Chakraborty Permanent Address, Vill:- 7 7 Smt.Alisha Chakraborty Abhoynagar, near Buddhamandir, Agartala . Pin:-799005 District:- West Tripura Contact No:- 9774326176 S/o:-Sri. Nilmani Chanda, Permanent Address, Vill:- 8 8 Sri.Bidyut Chanda Ba rasurma. -

Existing Health Care Services in Tripura

CHAPTER – IV EXISTING HEALTH CARE SERVICES IN TRIPURA 4.1 Present Health Care Services in Tripura This research work is oriented to provide an overview of the existing health care system and its utilization in India with special reference to Rural Tripura. Utilization is nothing but the satisfied demand. If at any given period of time, a part of population with a self-perceived medical problem thinks that the problem is worthy of treatment then they constitute a group with self-perceived need of care. Among those with a self-perceived need there will be some who will translate this need into the action of seeking care. Again part of those demanding will indeed obtain care. This group represents satisfied demand or utilization. In this chapter an attempt has been made to analyse the utilization of health care facilities in rural Tripura. But before going through the relevant details it is desirable to have a brief notion about the state profile of Tripura. 96 4.2 Tripura-State Profile a) Location Tripura is a hilly State in North East India, located on the extreme corner of the Indian sub –continent. It lies approximately between 22056‟N and 24032‟N northern latitudes and 91009‟E and 92020‟E eastern longitude. The State is bordered by the neighboring country Bangladesh (East Bengal) to the North, South and West and Indian State of Assam and Mizoram to the east. The length of its International border with Bangladesh is about 856 km (i.e. about 84 percent of its total border) while it has 53 km border with Assam and 109 km border with Mizoram. -

Political Parties in India

A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE www.amkresourceinfo.com Political Parties in India India has very diverse multi party political system. There are three types of political parties in Indiai.e. national parties (7), state recognized party (48) and unrecognized parties (1706). All the political parties which wish to contest local, state or national elections are required to be registered by the Election Commission of India (ECI). A recognized party enjoys privileges like reserved party symbol, free broadcast time on state run television and radio in the favour of party. Election commission asks to these national parties regarding the date of elections and receives inputs for the conduct of free and fair polls National Party: A registered party is recognised as a National Party only if it fulfils any one of the following three conditions: 1. If a party wins 2% of seats in the Lok Sabha (as of 2014, 11 seats) from at least 3 different States. 2. At a General Election to Lok Sabha or Legislative Assembly, the party polls 6% of votes in four States in addition to 4 Lok Sabha seats. 3. A party is recognised as a State Party in four or more States. The Indian political parties are categorized into two main types. National level parties and state level parties. National parties are political parties which, participate in different elections all over India. For example, Indian National Congress, Bhartiya Janata Party, Bahujan Samaj Party, Samajwadi Party, Communist Party of India, Communist Party of India (Marxist) and some other parties. State parties or regional parties are political parties which, participate in different elections but only within one 1 www.amkresourceinfo.com A M K RESOURCE WORLD GENERAL KNOWLEDGE state. -

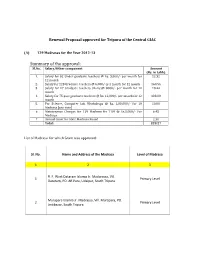

Renewal Proposal Approved for Tripura of the Central GIAC

Renewal Proposal approved for Tripura of the Central GIAC (A) 129 Madrasas for the Year 2012-13 Summary of the approval: Sl.No. Salary/Other component Amount (Rs. in Lakh) 1. Salary for 62 Under graduate teachers @ Rs. 3,000/- per month for 22.32 12 month 2. Salary for 223 Graduate teachers @ 6,000/- per month for 12 month 160.56 3. Salary for 27 Graduate teachers (Hons)@ 6000/- per month for 12 19.44 month 4. Salary for 75 post graduate teachers @ Rs. 12,000/- per month for 12 108.00 month 5. For Science, Computer lab, Workshops @ Rs. 1,00,000/- for 10 10.00 Madrasa [one time] 6 Maintenance Charges for 129 Madrasa for TLM @ Rs.5,000/- Per 6.45 Madrasa 7 Annual Grant for State Madrasa Board 2.50 Total: 329.27 List of Madrasa for which Grant was approved: Sl. No. Name and Address of the Madrasa Level of Madrasa 1 2 3 R. F. West Dataram Islamia Jr. Madarassa, Vill. 1 Primary Level Dataram, PO. AR Para, Udaipur, South Tripura Murapara Islamia Jr. Madrassa, Vill. Murapara, PO. 2 Primary Level Jintibazar, South Tripura Shalgara Jr. Muktab Madrassa, Vill. & PO. Shalgara, 3 Primary Level Udaipur, South Tripaur Hazarat Abubakkar Siddiquia Jr. Madrassa, PO. RK Pur, 4 Primary Level Udaipur, South Tripaur Darul Uloom Isamia Jr Madrassa, Vill Rajdhannagar, PO 5 Primary Level Jamjuri, Udaipur, South Tripaur Dakshin Chandrapur Jr. Madrassa, Vill. & PO South 6 Primary Level Chandrapur, Udaipur, South Tripaur Khilpara Jr. Madrassa, Vill. & PO Khilpara, Udaipur, 7 Primary Level South Tripaur Depachari Jr. -

International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI

SJIF Impact Factor: 6.047 Volume: 6 | November - October 2019 -2020 ISSN(Print ): 2250 – 2017 International Journal of Global Economic Light (JGEL) Journal DOI : https://doi.org/10.36713/epra0003 IDENTITY MOVEMENTS AND INTERNAL DISPLACEMENT IN ASSAM Ananda Chandra Ghosh Assistant Professor, Department of Political Science, Cachar College, Silchar,788001,Assam, India ABSTRACT Assam, the most populous state of North East India has been experiencing the problem of internal displacement since independence. The environmental factors like the great earth quake of 1950 displaced many people in the state. Flood and river bank erosion too have caused displacement of many people in Assam every year. But the displacement which has drawn the attention of the social scientists is the internal displacement caused by conflicts and identity movements. The Official Language Movement of 1960 , Language movement of 1972 and the Assam movement(1979-1985) were the main identity movements which generated large scale violence conflicts and internal displacement in post colonial Assam .These identity movements and their consequence internal displacement can not be understood in isolation from the ethno –linguistic composition, colonial policy of administration, complex history of migration and the partition of the state in 1947.Considering these factors in the present study an attempt has been made to analyze the internal displacement caused by Language movements and Assam movement. KEYWORDS: displacement, conflicts, identity movements, linguistic composition DISCUSSION are concentrated in the different corners of the state. Some of The state of Assam is considered as mini India. It is these Tribes have assimilated themselves and have become connected with main land of India with a narrow patch of the part and parcel of Assamese nationality. -

National Seminar on Quality Enhancement in Higher Education in Northeast India: Challenges and Opportunities

National Seminar On Quality Enhancement in Higher Education in Northeast India: Challenges and Opportunities Date: 25th & 26th February 2017 Organized by Internal Quality Assurance Cell (IQAC) Govt. Degree College, Dharmanagar North Tripura Venue: Govt. Degree College, Dharmanagar, North Tripura, NE, India Sponsored by: National Assessment and Accreditation Council (NAAC) Dear Sir/ Madam, Govt. Degree College Dharmanagar is organizing a national seminar on “Quality Enhancement in Higher Education in Northeast India: Challenges and Opportunities” on 25th & 26th February 2017. We look forward to your valuable contribution to make this endeavour a success. About Govt. Degree College Dharmanagar: Govt. Degree college, Dharmanagar is located in the North District of Tripura. It started functioning with B.A. (pass) course and with handful students in the premises of Dharmanagar Girls H.S (+2 stage) school on 21st September 1979. The college now offers degree programmes for both Pass and Honours in almost all the branches of Science, Commerce and Humanities. It is affiliated to Tripura Central University (UGC 2f & 12B recognized) and Accredited by NAAC (B++, CGPA= 2.79). The Institution is well connected by bus and train from Capital City Agartala, Guwahati and Silchar. Aims and Objectives of the Seminar: 1. To have an overview of the profile of higher educational institutions of North-eastern region of India. 2. To identify the difficulties faced by the higher educational institutions in Northeast India. 3. To find out suitable solutions to overcome those loopholes and to enhance quality in education. Scope and outline of the Seminar: Against the backdrop of NAAC being introduced to assess and accredited the higher education, we are trying to look from the perspective of India’s Northeast region. -

Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement by Dr

Global Journal of HUMAN-SOCIAL SCIENCE: D History Archaeology & Anthropology Volume 14 Issue 1 Version 1.0 Year 2014 Type: Double Blind Peer Reviewed International Research Journal Publisher: Global Journals Inc. (USA) Online ISSN: 2249-460x & Print ISSN: 0975-587X Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement By Dr. Anil Kumar Sarkar ABN Seal College, India Introduction- The present Darjeeling District was formed in 1866 where Kalimpong was transformed to the Darjeeling District. It is to be noted that during Bhutanese regime Kalimpong was within the Western Duars. After the Anglo-Bhutanese war 1866 Kalimpong was transferred to Darjeeling District and the western Duars was transferred to Jalpaiguri District of the undivided Bengal. Hence the Darjeeling District was formed with the ceded territories of Sikkim and Bhutan. From the very beginning both Darjeeling and Western Duars were treated excluded area. The population of the Darjeeling was Composed of Lepchas, Nepalis, and Bhotias etc. Mech- Rajvamsis are found in the Terai plain. Presently, Nepalese are the majority group of population. With the introduction of the plantation economy and developed agricultural system, the British administration encouraged Nepalese to Settle in Darjeeling District. It appears from the census Report of 1901 that 61% population of Darjeeling belonged to Nepali community. GJHSS-D Classification : FOR Code : 120103 Gorkha Identity and Separate Statehood Movement Strictly as per the compliance and regulations of: © 2014. Dr. Anil Kumar Sarkar. This is a research/review paper, distributed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution- Noncommercial 3.0 Unported License http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/3.0/), permitting all non-commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided the original work is properly cited. -

India's North-East Diversifying Growth Opportunities

INDIAN CHAMBER OF COMMERCE India’s North-East Diversifying Growth Opportunities www.pwc.com/in 2 ICC - PwC Report Foreword To be socially, and economically sustainable, India’s growth story needs to be inclusive. However, the country’s north east has been experiencing a comparatively slower pace of industrialisation and socio-economic growth. Though the region is blessed with abundant natural resources for industrial development and social development, they have not been utilised to their full potential. The region has certain distinct advantages. It is strategically located with access to the traditional domestic market of eastern India, along with proximity to the major states in the east and adjacent countries such as Bangladesh and Myanmar. The region is also a vantage entry point for the South-East Asian markets. The resource-rich north east with its expanses of fertile farmland and a huge talent pool could turn into one of India’s most prosperous regions. Yet, owing to its unique challenges, we believe that conventional market-based solutions may not work here, given the issues related to poor infrastructure and connectivity, unemployment and low economic development, law and order problems, etc. The government and the private sector need to collaborate and take the lead in providing solutions to these problems. More reform needs to be initiated in a range of areas, such as investment in agriculture, hydel power, infrastructure as well as in creating new avenues of growth through the development of vertically integrated food processing chains, market- linked skill development and cross-border trade. As multiple avenues for growth and development emerge, it is of paramount importance that the region, as a collective identity, embarks on a vibrant journey to realise the dreams of a better future.