American Oriental Society

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

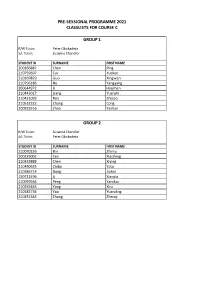

Classlists for C by Group

PRE-SESSIONAL PROGRAMME 2021 CLASSLISTS FOR COURSE C GROUP 1 R/W Tutor: Peter Obukadeta S/L Tutor: Suzanne Chandler STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200166887 Chen Ping 210759697 Cui Yuekun 210169829 Guo Xingwen 210796186 Hu Yangyang 200644972 Li Haozhan 210443017 Liang Yuanzhi 210421093 Ren Zhijiao 210532322 Zhang Cong 200925516 Zhao Yashan GROUP 2 R/W Tutor: Suzanne Chandler S/L Tutor: Peter Obukadeta STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210070226 Bin Zhimu 200329002 Cen Xiaofeng 210333888 Chen Xiying 210450635 Chiba Yota 210386714 Dong Jiahui 190711496 Li Xiaoxia 210059564 Peng Yanduo 210255465 Yang Xiru 210182736 Yao Yuanding 210252383 Zhang Zhenqi GROUP 3 R/W Tutor: Mark Heffernan S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210154386 Cai Zhenping 210462580 Ge Xiaodan 210648276 Hirunkhajonrote Kullanut 210182714 Huang Siwei 200141563 Kung Tzu-Ning 200305176 Punsri Punnatorn 200664774 Sayin Humeyra 210186446 Shehata Omar 171003323 Tutberidze Tea 200134624 Wang Shuo 200136019 Xu Ming 200278696 Yan Jiaxin 210357851 Yuan Lai 210029165 Zhang Anru 210219777 Zhang Jiasheng GROUP 4 R/W Tutor: Sherin White S/L Tutor: Alan Hart STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 200247588 Chen Chong 200349343 Li Cheng 210622933 Liang Wenxuan 210219618 Liu Huiyuan 210376298 Liu Zeyu 210237531 Mei Lyuke 200132620 Qi Shuyu 210681907 Wang Handuo 200015356 Wu Zhuoyue 200071994 Xie Kaijun GROUP 5 R/W Tutor: Chukwudi Dozie S/L Tutor: Nora Mikso STUDENT ID SURNAME FIRST NAME 210563304 Almalek Ahmed 210186309 Altamimi Saud 210251102 Cheng Han-Yu 210349823 Guo Wenyuan 210239409 -

Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: from Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace

EUGENE Y. WANG Mirror, Moon, and Memory in Eighth-Century China: From Dragon Pond to Lunar Palace Why the Flight-to-the-Moon The Bard’s one-time felicitous phrasing of a shrewd observation has by now fossilized into a commonplace: that one may “hold, as ’twere, the mirror up to nature; to show virtue her own feature, scorn her own image, and the very age and body of the time his form and pressure.”1 Likewise deeply rooted in Chinese discourse, the same analogy has endured since antiquity.2 As a commonplace, it is true and does not merit renewed attention. When presented with a physical mirror from the past that does register its time, however, we realize that the mirroring or showing promised by such a wisdom is not something we can take for granted. The mirror does not show its time, at least not in a straightforward way. It in fact veils, disfi gures, and ultimately sublimates the historical reality it purports to refl ect. A case in point is the scene on an eighth-century Chinese mirror (fi g. 1). It shows, at the bottom, a dragon strutting or prancing over a pond. A pair of birds, each holding a knot of ribbon in its beak, fl ies toward a small sphere at the top. Inside the circle is a tree fl anked by a hare on the left and a toad on the right. So, what is the design all about? A quick iconographic exposition seems to be in order. To begin, the small sphere refers to the moon. -

French Names Noeline Bridge

names collated:Chinese personal names and 100 surnames.qxd 29/09/2006 13:00 Page 8 The hundred surnames Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Pinyin Hanzi (simplified) Wade Giles Other forms Well-known names Zang Tsang Zang Lin Zhu Chu Gee Zhu Yuanzhang, Zhu Xi Zeng Tseng Tsang, Zeng Cai, Zeng Gong Zhu Chu Zhu Danian Dong, Zhu Chu Zhu Zhishan, Zhu Weihao Jeng Zhu Chu Zhu jin, Zhu Sheng Zha Cha Zha Yihuang, Zhuang Chuang Zhuang Zhou, Zhuang Zi Zha Shenxing Zhuansun Chuansun Zhuansun Shi Zhai Chai Zhai Jin, Zhai Shan Zhuge Chuko Zhuge Liang, Zhan Chan Zhan Ruoshui Zhuge Kongming Zhan Chan Chaim Zhan Xiyuan Zhuo Cho Zhuo Mao Zhang Chang Zhang Yuxi Zi Tzu Zi Rudao Zhang Chang Cheung, Zhang Heng, Ziche Tzuch’e Ziche Zhongxing Chiang Zhang Chunqiao Zong Tsung Tsung, Zong Xihua, Zhang Chang Zhang Shengyi, Dung Zong Yuanding Zhang Xuecheng Zongzheng Tsungcheng Zongzheng Zhensun Zhangsun Changsun Zhangsun Wuji Zou Tsou Zou Yang, Zou Liang, Zhao Chao Chew, Zhao Kuangyin, Zou Yan Chieu, Zhao Mingcheng Zu Tsu Zu Chongzhi Chiu Zuo Tso Zuo Si Zhen Chen Zhen Hui, Zhen Yong Zuoqiu Tsoch’iu Zuoqiu Ming Zheng Cheng Cheng, Zheng Qiao, Zheng He, Chung Zheng Banqiao The hundred surnames is one of the most popular reference Zhi Chih Zhi Dake, Zhi Shucai sources for the Han surnames. It was originally compiled by an Zhong Chung Zhong Heqing unknown author in the 10th century and later recompiled many Zhong Chung Zhong Shensi times. The current widely used version includes 503 surnames. Zhong Chung Zhong Sicheng, Zhong Xing The Pinyin index of the 503 Chinese surnames provides an access Zhongli Chungli Zhongli Zi to this great work for Western people. -

Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? a Study of Early Contacts Between Indo-Iranians and Chinese

SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS Number 216 October, 2011 Is Shuma the Chinese Analog of Soma/Haoma? A Study of Early Contacts between Indo-Iranians and Chinese by ZHANG He Victor H. Mair, Editor Sino-Platonic Papers Department of East Asian Languages and Civilizations University of Pennsylvania Philadelphia, PA 19104-6305 USA [email protected] www.sino-platonic.org SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS FOUNDED 1986 Editor-in-Chief VICTOR H. MAIR Associate Editors PAULA ROBERTS MARK SWOFFORD ISSN 2157-9679 (print) 2157-9687 (online) SINO-PLATONIC PAPERS is an occasional series dedicated to making available to specialists and the interested public the results of research that, because of its unconventional or controversial nature, might otherwise go unpublished. The editor-in-chief actively encourages younger, not yet well established, scholars and independent authors to submit manuscripts for consideration. Contributions in any of the major scholarly languages of the world, including romanized modern standard Mandarin (MSM) and Japanese, are acceptable. In special circumstances, papers written in one of the Sinitic topolects (fangyan) may be considered for publication. Although the chief focus of Sino-Platonic Papers is on the intercultural relations of China with other peoples, challenging and creative studies on a wide variety of philological subjects will be entertained. This series is not the place for safe, sober, and stodgy presentations. Sino- Platonic Papers prefers lively work that, while taking reasonable risks to advance the field, capitalizes on brilliant new insights into the development of civilization. Submissions are regularly sent out to be refereed, and extensive editorial suggestions for revision may be offered. Sino-Platonic Papers emphasizes substance over form. -

Gateless Gate Has Become Common in English, Some Have Criticized This Translation As Unfaithful to the Original

Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Original Collection in Chinese by Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Page ii Frontspiece “Wú Mén Guān” Facsimile of the Original Cover Page iii Page iv Wú Mén Guān The Barrier That Has No Gate Chán Master Wúmén Huìkāi (1183-1260) Questions and Additional Comments by Sŏn Master Sǔngan Compiled and Edited by Paul Dōch’ŏng Lynch, JDPSN Sixth Edition Before Thought Publications Huntington Beach, CA 2010 Page v BEFORE THOUGHT PUBLICATIONS HUNTINGTON BEACH, CA 92648 ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. COPYRIGHT © 2010 ENGLISH VERSION BY PAUL LYNCH, JDPSN NO PART OF THIS BOOK MAY BE REPRODUCED OR TRANSMITTED IN ANY FORM OR BY ANY MEANS, GRAPHIC, ELECTRONIC, OR MECHANICAL, INCLUDING PHOTOCOPYING, RECORDING, TAPING OR BY ANY INFORMATION STORAGE OR RETRIEVAL SYSTEM, WITHOUT THE PERMISSION IN WRITING FROM THE PUBLISHER. PRINTED IN THE UNITED STATES OF AMERICA BY LULU INCORPORATION, MORRISVILLE, NC, USA COVER PRINTED ON LAMINATED 100# ULTRA GLOSS COVER STOCK, DIGITAL COLOR SILK - C2S, 90 BRIGHT BOOK CONTENT PRINTED ON 24/60# CREAM TEXT, 90 GSM PAPER, USING 12 PT. GARAMOND FONT Page vi Dedication What are we in this cosmos? This ineffable question has haunted us since Buddha sat under the Bodhi Tree. I would like to gracefully thank the author, Chán Master Wúmén, for his grace and kindness by leaving us these wonderful teachings. I would also like to thank Chán Master Dàhuì for his ineptness in destroying all copies of this book; thankfully, Master Dàhuì missed a few so that now we can explore the teachings of his teacher. -

The Conceptions of “The Distinction of Yi (Barbarians) and Xia(Chinese)”[夷夏之

The Conceptions of “the Distinction of Yi (Barbarians) and Xia(Chinese)”[夷夏之 辨] in Chinese Culture and Society –Culturalism or Cultural Chauvinism? Jau-hwa Chen [email protected] Abstract: The universal applicability of the Confucian ethics is shadowed by the concept of the yi/xia distinction. There are two theses to solve the problem: the culturalism and the ethnicity thesis. Though the culturalism and the ethnicity thesis tried very hard to solve the inconsistence in the Confucian doctrine, the problem is more complicated than solved. The conceptions of yi/xia distinction come originally from Chunqiu [春 秋], the Spring and Autumn Annals, interpreted by the three traditional commentaries, Zuo zhuan [左傳], Gongyang zhuan [公羊傳] and Gulian zhuan [轂梁傳]. Firstly, we need to investigate the historic contexts of the conceptions in the discourses of the hegemony to know its moral and political implication. Secondly, the different applications of the concept are implicitly related to a unilinear sage-kings tradition, interpreted by Mencius as an alternative of the hegemony, which can be used to exclude other ethnic groups of living together with the later so-called Han people. Mencius criticizes the competition for the hegemony in the Chunqiu and Warring States era, but is not critical enough against the emperor and his families centered political order. And lastly, in Yuan Dao, the opening treatise of the Huainanzi, instead of following the unilinear sage-kings tradition, to identify what is Chinese and what is not, a naturalistic and pluralistic ways of living are provided, which can be interpreted as a solution of the universal applicability of the Confucian ethics, to free itself from the xia (Chinese) culture centered world picture. -

Political Thoughtyuri Pinespolitical Thought

13 POLITICAL THOUGHTYURI PINESPOLITICAL THOUGHT Yuri Pines* The three centuries that preceded the establishment of the Chinese empire in 221 bce were an age of exceptional intellectual flourishing. No other period in the history of Chinese thought can rival these centuries in creativity, boldness, ideological diversity, and long-term impact. Val- ues, perceptions, and ideals shaped amid intense intellectual debates before the imperial unifi- cation contributed decisively to the formation of the political, social, and ethical orientations that we identify today with traditional Chinese culture. More broadly, the ideas of rival thinkers formed an ideological framework within which the Chinese empire functioned from its incep- tion until its very last decades. These ideas stand at the focus of the present chapter. The centuries under discussion are often dubbed the age of the “Hundred Schools of Thought.” The school designations were developed primarily by the Han (206/202 bce–220 ce) literati (Smith 2003; Csikszentmihalyi and Nylan 2003) as a classificatory device for the variety of pre-imperial texts. This classification, even if belated, may be heuristically convenient insofar as it groups the texts according to their distinct ideological emphases, distinct vocabulary, and distinct argumentative practices. For instance, followers of Confucius (551–479 bce) and Mozi 墨子 (ca. 460–390 bce) were prone to prioritize morality over pure political considerations, in distinction from those thinkers who are – quite confusingly (Goldin 2011a) – dubbed Legalists (fa jia 法家). Confucians (Ru 儒) and Legalists also differed markedly with regard to the nature of elite belonging (see later). This said, it is fairly misleading to imagine “schools” as coherent ideological camps, as was often done through the twentieth century and beyond. -

On the Rhetoric of Treason in the Shiji

“Awaiting The Wise of a Future Generation”: On the Rhetoric of Treason in the Shiji (Dorothee Schaab-Hanke) The rhetorical device I chose for analysis in my paper is that of allusion. More specifically, my focus lies on the rhetorical and political function of altogether five text passages in the Shiji (The Scribe’s Record), a text that was probably finalized around the year 86 BCE. The “author of the Shiji” – please allow me that I postpone the tricky question of author- ship to the Shiji a bit here – in each of these passages addresses as his readers wise men of a future generation of whom he hoped that they will prove worthy to make use of the work that he had compiled and left for posterity. Closer examination reveals that these five text passages all al- lude to one passage of the Gongyang zhuan, one of the three earliest texts that interpreted the Chunqiu (Spring and Autumn) annals, a by its very nature rather terse chronicle of the state of Lu, spanning the years from 721 to 481 BCE. In my written paper, I have discussed three major topics. In my short presentation I will highlight them first and then discuss them in a sum- marized form. First, if one reads the five passages in the Shiji in which the historiog- rapher alludes to the here relevant passage of the Gongyang zhuan in the context of the chapters in which they are contained and if one relates the conclusions to be drawn from these chapters to each other, various facets of an overall political message become discernible, namely a rather criti- cal assessment of Emperor Wu (r. -

The Past As a Messianic Vision

Edinburgh Research Explorer The past as a messianic vision Citation for published version: Gentz, J 2005, The past as a messianic vision: Historical thought and strategies of sacralization in the early Gongyang tradition. in H Schmidt-Glintzer, A Mittag & J Rüsen (eds), Historical Truth, Historical Criticism, and Ideology: Chinese Historiography and Historical Culture from a New Comparative Perspective. Brill, Leiden, pp. 227-254. Link: Link to publication record in Edinburgh Research Explorer Document Version: Peer reviewed version Published In: Historical Truth, Historical Criticism, and Ideology General rights Copyright for the publications made accessible via the Edinburgh Research Explorer is retained by the author(s) and / or other copyright owners and it is a condition of accessing these publications that users recognise and abide by the legal requirements associated with these rights. Take down policy The University of Edinburgh has made every reasonable effort to ensure that Edinburgh Research Explorer content complies with UK legislation. If you believe that the public display of this file breaches copyright please contact [email protected] providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Download date: 25. Sep. 2021 THE PAST AS A MESSIANIC VISION: HISTORICAL THOUGHT AND STRATEGIES OF SACRALIZATION IN THE EARLY GONGYANG TRADITION Joachim Gentz Introduction I would like to divide my paper into five parts: 1. The past (this will imply the Gongyang zhuan’s historical criticism of sources and its historiographical attitude towards the past): 2. as a messianic vision (this will deal with the function and application of the historical material for the Gongyang zhuan’s own vision): 3. -

By Qi Biaojia

This article was downloaded by: [University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign] On: 28 December 2014, At: 11:29 Publisher: Routledge Informa Ltd Registered in England and Wales Registered Number: 1072954 Registered office: Mortimer House, 37-41 Mortimer Street, London W1T 3JH, UK Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes: An International Quarterly Publication details, including instructions for authors and subscription information: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/tgah20 Qi Biaojia' s ‘Footnotes to Allegory Mountain’: introduction and translation1 Duncan Campbell a a Victoria University of Wellington , UK Published online: 31 May 2012. To cite this article: Duncan Campbell (1999) Qi Biaojia' s ‘Footnotes to Allegory Mountain’: introduction and translation1 , Studies in the History of Gardens & Designed Landscapes: An International Quarterly, 19:3-4, 243-271, DOI: 10.1080/14601176.1999.10435576 To link to this article: http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/14601176.1999.10435576 PLEASE SCROLL DOWN FOR ARTICLE Taylor & Francis makes every effort to ensure the accuracy of all the information (the “Content”) contained in the publications on our platform. However, Taylor & Francis, our agents, and our licensors make no representations or warranties whatsoever as to the accuracy, completeness, or suitability for any purpose of the Content. Any opinions and views expressed in this publication are the opinions and views of the authors, and are not the views of or endorsed by Taylor & Francis. The accuracy of the Content should not be relied upon and should be independently verified with primary sources of information. Taylor and Francis shall not be liable for any losses, actions, claims, proceedings, demands, costs, expenses, damages, and other liabilities whatsoever or howsoever caused arising directly or indirectly in connection with, in relation to or arising out of the use of the Content. -

Preliminary Pages

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Ascending the Hall of Great Elegance: the Emergence of Drama Research in Modern China A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Doctor of Philosophy in History by Hsiao-Chun Wu 2016 © Copyright by Hsiao-Chun Wu 2016 ABSTRACT OF THE DISSERTATION Ascending the Hall of Great Elegance: the Emergence of Drama Research in Modern China by Hsiao-Chun Wu Doctor of Philosophy in History University of California, Los Angeles, 2016, Professor Andrea Sue Goldman, Chair This dissertation captures a critical moment in China’s history when the interest in opera transformed from literati divertissement into an emerging field of scholarly inquiry. Centering around the activities and writings of Qi Rushan (1870-1962), who played a key role both in reshaping the modes of elite involvement in opera and in systematic knowledge production about opera, this dissertation explores this transformation from a transitional generation of theatrical connoisseurs and researchers in early twentieth-century China. It examines the many conditions and contexts in the making of opera—and especially Peking opera—as a discipline of modern humanistic research in China: the transnational emergence of Sinology, the vibrant urban entertainment market, the literary and material resources from the past, and the bodies and !ii identities of performers. This dissertation presents a critical chronology of the early history of drama study in modern China, beginning from the emerging terminology of genre to the theorization and the making of a formal academic discipline. Chapter One examines the genre-making of Peking Opera in three overlapping but not identical categories: temporal, geographical-political, and aesthetic. -

20180115-CHN-Eng.Pdf (1.114Mb)

Meeting Report GO WHO CHINA: WORKING IN WHO 15 January 2018 Beijing, People's Republic of China GO WHO China: Working in WHO 15 January 2018 Beijing, People's Republic of China WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION REGIONAL OFFICE FOR THE WESTERN PACIFIC English only MEETING REPORT GO WHO CHINA: WORKING IN WHO Convened by: WORLD HEALTH ORGANIZATION REGIONAL OFFICE FOR THE WESTERN PACIFIC Beijing, People’s Republic of China 15 January 2018 Not for sale Printed and distributed by: World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific Manila, Philippines February 2018 NOTE The views expressed in this report are those of the participants of the Go WHO Workshops to Improve Geographical Representation of WHO Staff and do not necessarily reflect the policies of the conveners. This report has been prepared by the World Health Organization Regional Office for the Western Pacific for Member States in the Region and for those who participated in the Go WHO Workshops to Improve Geographical Representation of WHO Staff in Beijing, People’s Republic of China on 15 January 2018. CONTENTS SUMMARY ............................................................................................................................................ 1 1. INTRODUCTION .............................................................................................................................. 2 1.1 Background ................................................................................................................................... 2 1.2 Workshop objectives ....................................................................................................................