The Implementation of a Needleless IV System and Its Impact in Needlestick Injuries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Technical Considerations for Pen, Jet, and Related Injectors Intended for Use with Drugs and Biological Products

Guidance for Industry and FDA Staff: Technical Considerations for Pen, Jet, and Related Injectors Intended for Use with Drugs and Biological Products Additional copies are available from: Office of Combination Products Office of Special Medical Programs Office of the Commissioner Food and Drug Administration 10903 New Hampshire Avenue, WO-32 Hub 5129 Silver Spring, MD 20993 (Tel) 301-796-8930 (Fax) 301-796-8619 http://www.fda.gov/CombinationProducts/default.htm This document finalizes the draft guidance issued in April 2009. For questions regarding this document, contact the Office of Combination Products at [email protected] or Patricia Y. Love, MD at 301-796-8933 or [email protected] U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Food and Drug Administration Center for Devices and Radiological Health, Center for Drug Evaluation Research, Center for Biologics Evaluation and Research, and Office of Combination Products in the Office of the Commissioner June 2013 Contains Nonbinding Recommendations Table of Contents INTRODUCTION.....................................................................................................................3 BACKGROUND .......................................................................................................................4 SECTION I: SCIENTIFIC AND TECHNICAL CONSIDERATIONS.............................5 A. INJECTOR DESCRIPTION .............................................................................................5 B. DESIGN FEATURES.........................................................................................................9 -

Drug Delivery Products

INDUSTRY MARKET RESEARCH FOR BUSINESS LEADERS, STRATEGISTS, DECISION MAKERS CLICK TO VIEW Table of Contents 2 List of Tables & Charts 3 Study Overview 4 Sample Text, Table & Chart 5 Sample Profile, Table & Forecast 6 Order Form & Corporate Use License 7 About Freedonia, Custom Research, Related Studies, 8 Drug Delivery Products US Industry Study with Forecasts for 2015 & 2020 Study #2829 | January 2012 | $4800 | 337 pages The Freedonia Group 767 Beta Drive www.freedoniagroup.com Cleveland, OH • 44143-2326 • USA Toll Free US Tel: 800.927.5900 or +1 440.684.9600 Fax: +1 440.646.0484 E-mail: [email protected] Study #2829 January 2012 Drug Delivery Products $4800 337 Pages US Industry Study with Forecasts for 2015 & 2020 Table of Contents Starch Compounds ...................................62 Infusion Pumps ..................................... 150 Cyclodextrins .......................................62 Other Infusion Products .......................... 152 Dextrates ............................................62 Enteral Feeding Supplies ..................... 152 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Dextrin ...............................................63 IV Accessories ................................... 153 Maltodextrin ........................................63 Parenteral Drug Delivery Devices .................. 154 MARKET ENVIRONMENT Sugars & Polyols ......................................63 Prefillable Syringes ................................ 155 Sucrose ...............................................63 Injectors .......................................... -

2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats*

VETERINARY PRACTICE GUIDELINES 2020 AAHA Anesthesia and Monitoring Guidelines for Dogs and Cats* Tamara Grubb, DVM, PhD, DACVAAy, Jennifer Sager, BS, CVT, VTS (Anesthesia/Analgesia, ECC)y, James S. Gaynor, DVM, MS, DACVAA, DAIPM, CVA, CVPP, Elizabeth Montgomery, DVM, MPH, Judith A. Parker, DVM, DABVP, Heidi Shafford, DVM, PhD, DACVAA, Caitlin Tearney, DVM, DACVAA ABSTRACT Risk for complications and even death is inherent to anesthesia. However, the use of guidelines, checklists, and training can decrease the risk of anesthesia-related adverse events. These tools should be used not only during the time the patient is unconscious but also before and after this phase. The framework for safe anesthesia delivered as a continuum of care from home to hospital and back to home is presented in these guidelines. The critical importance of client commu- nication and staff training have been highlighted. The role of perioperative analgesia, anxiolytics, and proper handling of fractious/fearful/aggressive patients as components of anesthetic safety are stressed. Anesthesia equipment selection and care is detailed. The objective of these guidelines is to make the anesthesia period as safe as possible for dogs and cats while providing a practical framework for delivering anesthesia care. To meet this goal, tables, algorithms, figures, and “tip” boxes with critical information are included in the manuscript and an in-depth online resource center is available at aaha.org/anesthesia. (J Am Anim Hosp Assoc 2020; 56:---–---. DOI 10.5326/JAAHA-MS-7055) AFFILIATIONS Other recommendations are based on practical clinical experience and From Washington State University College of Veterinary Medicine, Pullman, a consensus of expert opinion. -

United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.458,536 B2 Felts Et Al

USOO9458536B2 (12) United States Patent (10) Patent No.: US 9.458,536 B2 Felts et al. (45) Date of Patent: Oct. 4, 2016 (54) PECVD COATING METHODS FOR CAPPED (52) U.S. Cl. SYRINGES, CARTRIDGES AND OTHER CPC ........... C23C 16/401 (2013.01); A61 B 5/1405 ARTICLES (2013.01); A61 B 5/153 (2013.01); (71) Applicants: John T. Felts, Alameda, CA (US); (Continued)Continued Thomas E. Fisk, Green Valley, AZ (58) Field of Classification Search (US); Shawn Kinney, Wayland, MA CPC ... A61M 5/178; C23C 16/045; A61L 31/08; (US); Christopher Weikart, Auburn, A61L 31/14 AL (US); Benjamin Hunt, Auburn, AL USPC . 427/2.28, 2.1, 230, 237, 569 (US); Adrian Raiche, Auburn, AL Seeee applicationa1Ca1O fileTO f CO.plet SeaClh history1SOW. (US); Brian Fitzpatrick, West Chester, (56) References Cited PA (US); Peter J. Sagona, Pottstown, PA (US); Adam Stevenson, Opelika, U.S. PATENT DOCUMENTS AL (US) 3,274,267 A 9, 1966 Chow (72) Inventors: John T. Felts, Alameda, CA (US); 3,297,465. A 1, 1967 Connel Thomas E. Fisk, Green Valley, AZ (Continued) (US); Shawn Kinney, Wayland, MA (US); Christopher Weikart, Auburn, FOREIGN PATENT DOCUMENTS AL (US); Benjamin Hunt, Auburn, AL (US); Adrian Raiche, Auburn, AL A. SSR, 1939. (US); Brian Fitzpatrick, West Chester, Continued PA (US); Peter J. Sagona, Pottstown, (Continued) PA (US); Adam Stevenson, Opelika, AL (US) OTHER PUBLICATIONS Hanlon, Adriene Lepiane, Pak, Chung K. Pawlikowski, Beverly A. (73) Assignee: s MEDICAL PRODUCTS, INC., Decision on Appeal. Appeal No. 2005-1693, U.S. Appl. No. Auburn, AL (US) 10/192,333, dated Sep. -

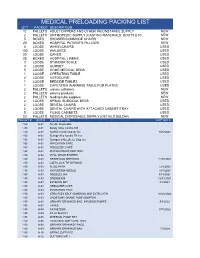

Montgomery Preloading

MEDICAL PRELOADING PACKING LIST QTY PACKED DESCRIPTION 12 PALLETS ADULT DIPPERS AND OTHER INCONSTANCE SUPPLY NEW 2 PALLETS ORTHOPEDIC SUPPLY (CASTING MATERIALS, BOOTS ETC. NEW 5 BOXES SHOWER/COMMODE CHAIRS NEW 20 BOXES HOSPITAL PATIENT'S PILLOWS NEW 3 LOOSE WHEELCHAIRS USED 100 LOOSE WALKERS USED 20 LOOSE CANES USED 25 BOXES HOSPITAL LINENS USED 3 LOOSE STANDUP SCALE USED 3 LOOSE GURNEY USED 5 LOOSE HOME MEDICAL BEDS USED 1 LOOSE OPERATING TABLE USED 2 LOOSE AUTOCLAVE USED 1 LOOSE BEDSIDE TABLES USED 1 LOOSE CAFETERIA WARMING TABLE FOR PLATES USED 2 PALLETS urinary catheters NEW 2 PALLETS ostomy products NEW 2 PALLETS feeding tube supplies NEW 2 LOOSE SPINAL SURGICAL BEDS USED 2 LOOSE DENTAL CHAIRS USED 2 LOOSE DENTAL CHAIRS WITH ATTACHED CABINET/TRAY USED 5 LOOSE FILING CABINETS USED 23 PALLETS MEDICAL DISPOSABLE SUPPLY (DETAILS BELOW) NEW PALLET # BOX # DESCRIPTION EXP DATE 1-50 A-01 Needle Disposable 1-50 A-01 Safety Glide Combo 3ML 1-50 A-01 Syr/Ndl Combo Safety 1cc 9/26/2023 1-50 A-01 Syringe W/o Needle TB 1cc 1-50 A-01 Syringes w/Needle LL Disp 3cc 1-50 A-01 IRRIGATION SYRG 1-50 A-01 NEBULIZER CAPS 1-50 A-01 PISTON IRRIGATION TRAY 1-50 A-02 VITAL WRAP SYSTEM 1-50 A-03 GRANFOAM DRESSING 11/30/2021 1-50 A-03 LUER LOCK TIP SYRINGE 1-50 A-03 FLUID PATH 12/1/2023 1-50 A-03 HYPODERM NEEDLE 10/1/2023 1-50 A-03 NEEDLES MIX 9/19/2021 1-50 A-03 DRESSINGS 12/31/2021 1-50 A-03 EXTENTN SET 8/1/2024 1-50 A-03 NEBULIZER CAPS 1-50 A-03 IRRIGATION TRAY 1-50 A-03 UTRA FLEX SELF ADHERING MLE EXTR CATH 10/28/2022 1-50 A-03 UROSTOMY DRANE TUBE ADOPTER -

Comparative Hypodermic Needle Sharpness Among Major Brands

Comparative Hypodermic Needle Sharpness Among Major Brands: Results of an Independent Study Background This study compared needles made by Terumo with those made by Becton, Dickinson and Company (BD), It is generally accepted that needle sharpness is a Covidien (manufacturer of Kendall™ and Monoject™ key feature of any well-designed syringe with needle. brands), and Nipro Medical Corporation. To ensure Sharper needles provide patients with more comfortable objectivity, tests were conducted by DDL, an injections, thereby providing both patient and clinician independent laboratory in Eden Prairie, Minnesota, with a more satisfying injection experience. under controlled conditions in accordance with Does needle sharpness vary from brand to brand? Are applicable standard good laboratory practices.* one manufacturer’s needles generally sharper than those of another? These questions are answered by Sharpness test methodology this study, which assessed and quantified comparative This evaluation was based on the hypothesis that needle sharpness among major brands commonly used a sharper needle would require less force to penetrate in today’s clinical settings. standardized, surrogate skin material. The test scenario most important to The 2 tests (with and without vial penetration) involved patient comfort—skin injection quantitatively measuring the force needed to penetrate this material. To quantify relative sharpness, penetration Needles and syringes are commonly used for drawing up force was measured using Instron® testing equipment medications, mixing medications, accessing ports, and with a load cell—a standard device for measuring skin injection. The goal of this study was to determine needle penetration force. relative needle sharpness specifically for skin injection— the use that most affects patient comfort. -

(12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0051466A1 FARR Et Al

US 2016.005 1466A1 (19) United States (12) Patent Application Publication (10) Pub. No.: US 2016/0051466A1 FARR et al. (43) Pub. Date: Feb. 25, 2016 (54) NOVEL FORMULATIONS FORTREATMENT Publication Classification OF MIGRAINE (51) Int. Cl. 71) Applipplicant: ZOGENIX,9 INC.... E.EmeryV1lle, ille, CA (US A619/00 2006.O1 A613 L/478 (2006.01) (72) Inventors: Stephen J. FARR, Orinda, CA (US); A613 L/4045 (2006.01) John TURANIN, Danville, CA (US); (52) U.S. Cl. Roger HAWLEY, Rancho Santa Fe, CA CPC ........... A61 K9/0019 (2013.01); A61 K3I/4045 SS Jeffrey A. Schuster, Bolinas, CA (2013.01); A61 K31/4178 (2013.01) (57) ABSTRACT (21) Appl. No.: 14/930,982 Systems and methods are described for treating un-met medi (22) Filed: Nov. 3, 2015 cal needs in migraine and related conditions such as cluster headache. Included are treatments that are both rapid onset Related U.S. Application Data and long acting, which include Sustained release formula tions, and combination products. Also included are treat (60) Continuationonunuation oIof application No. 13/863,686,oso, filedIlled on ments ford multiplecombination symptoms products. of migraine, Also included especially head Apr.of 16, 2013, which is a division220 of application No. acheh andd nausea andd Vomiting. Systems thath are se1f filed as -application - - - No. PCT/US2009/002533• 1s s on Apr.s contained, portable, prefilled, and simple to self administer at 24, 2009 the onset of a migraine attack a disclosed, and preferably s include a needle-free injector and a high Viscosity formula (60) Provisional application No. 61/048.463, filed on Apr. -

Delivery Systems Equipment

CHAPTER 4 Delivery Systems Equipment CHAPTER OBJECTIVES ■ Identify the different parts of a syringe. ■ Identify the different types of syringes available and their unique characteristics. ■ Select the appropriate syringe to measure a given volume based on the syringe’s calibrations. ■ Identify the different parts of the needle. ■ Describe fi lter needles, fi lter straws, and vented needles. ■ Identify when a fi lter needle or fi lter straw is used. ■ Identify when a vented needle is used. ■ Describe the fi lters used to sterilize products. ■ Explain the advantages of a needleless system. ■ Explain the difference between large-volume parenterals and piggybacks. ■ Compare the advantages and disadvantages of glass bottles versus plastic bags. ■ Explain the characteristics of a single-dose vial and a multiple-dose vial. ■ Describe the advantages and disadvantages of vials and ampules. ■ Explain HEPA fi ltration. ■ Compare and contrast the use of laminar airfl ow workbenches (LAFWs), biological safety cabinets (BSCs), and compounding aseptic isolators. ■ Describe the proper cleaning procedures for an airfl ow hood. KEY TERMS ampule—a sealed glass container that contains a single dose fi lter straws—thin, sterile straws with a fi lter molded into of medication the hub; used to draw fl uid from an ampule bevel—the slanted, pointed tip of a needle gauge—the diameter of the opening of a needle, or the biological safety cabinet (BSC)—a vertical fl ow hood that lumen uses HEPA-fi ltered air that fl ows vertically (from the top HEPA fi lter—a high-effi ciency particulate -

Oral Delivery of Biologics Using Drug-Device Combinations

Oral delivery of biologics using drug-device combinations The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Caffarel-Salvador, Ester et al., "Oral delivery of biologics using drug- device combinations." Current Opinion in Pharmacology 36 (October 2017): 8-13 doi. 10.1016/j.coph.2017.07.003 ©2017 Authors As Published https://dx.doi.org/10.1016/J.COPH.2017.07.003 Publisher Elsevier BV Version Author's final manuscript Citable link https://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/128617 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivs License Detailed Terms http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/ HHS Public Access Author manuscript Author ManuscriptAuthor Manuscript Author Curr Opin Manuscript Author Pharmacol. Author Manuscript Author manuscript; available in PMC 2018 October 01. Published in final edited form as: Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2017 October ; 36: 8–13. doi:10.1016/j.coph.2017.07.003. Oral delivery of biologics using drug-device combinations Ester Caffarel-Salvador1,2,*, Alex Abramson2,*, Robert Langer1,2,§, and Giovanni Traverso2,3,§ 1Institute for Medical Engineering and Science, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA 02139, USA 2Department of Chemical Engineering and Koch Institute for Integrative Cancer Research, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, Massachusetts 02139, USA 3Division of Gastroenterology, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Harvard Medical School, Boston, Massachusetts 02115, USA Abstract Orally administered devices could enable the systemic uptake of biologic therapeutics by engineering around the physiological barriers present in the gastrointestinal (GI) tract. Such devices aim to shield cargo from degradative enzymes and increase the diffusion rate of medication through the GI mucosa. -

Product Catalog Regional Anesthesia

Product Catalog Regional Anesthesia Regional Anesthesia NEW DETAILS SEPARATE THE GOOD FROM THE GREAT. Pajunk Components made in Germany. Procedural TraysTrays assembled in USA. REGIONAL ANESTHESIA TRAYS FROM PAJUNKPAJUNK Are all Regional Anesthesia procedural trays the same? Almost. But they differ in the details. Learn more about the details that differentiate the brand new Pajunk procedural trays from the crowd at www.pajunktrays.com REQUEST YOUR TRIAL SAMPLES NOW AND MAKE A DIFFERENCE! TollToll Free : +1 (888) 972-5865 · [email protected] · www.pajunktrays.com Table of Contents 1 NERVE BLOCKS 2 SPINAL Single Shot Needles SPROTTE® Needles 22 SonoPlex 4 Introducer Needle 23 SonoBlock 4 Spinal Trays 24 SonoTAP 5 SonoLong Needle 5 TuohySono 6 3 EPIDURAL UniPlex NanoLine 6 EpiLong Sets 26 EpiLong Soft Set 27 Catheters EpiLong Soft Sono Sets 28 E-Cath 7 EpiLong Catheters 29 E-Cath Plus 8 Tuohy Needles 29 SonoLong Echo 9 StimuLong Sono Tsui 30 SonoLong Curl Echo 10 Crawford 31 SonoLong Sono 11 Accessories 31 StimuLong Sono II 12 PlexoLong NanoLine 13 Epidural Trays 32 Accessories NerveGuard 14 4 CSE MultiStim ECO 14 EpiSpin Lock 34 MultiStim SENSOR 15 Continuous Spinal-Epidural Trays 35 MultiStim SWITCH 15 MultiStim Nerve Stimulator Accessories 16 Safersonic 17 Accessories 17 Ambu® ACTion™ Block Pump 18 Nerve Block Trays 19 Luer and NRFit options available. SonoPlex II SonoBlock II Echogenic, Stimulating Echogenic, Non-Stimulating Single Shot Needle SingleShot Needle 1 Cornerstone Reflectors (360°) Cornerstone Reflectors (360°) NanoLine -

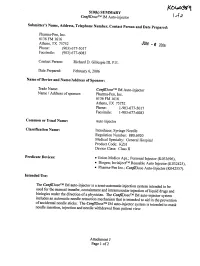

510(K) SUMMARY Confidosetm IM Auto-Injector Submitter's Name, Address, Telephone Number, Contact Person and Date Prepared

510(k) SUMMARY ConfiDoseTM IM Auto-injector Submitter's Name, Address, Telephone Number, Contact Person and Date Prepared: Pharma-Pen, Inc. 6136 FM 1616 Athens, TX 75752 JUN 2006 Phone: (903) 677-5017 Facsimile: (903) 677-6083 Contact Person: Richard D. Gillespie III, P.E. Date Prepared: February 6, 2006 Name of Device and Name/Address of Sponsor: Trade Name: ConfiDoseTM IM Auto-injector Name / Address of sponsor: Pharma-Pen, Inc. 6136 FM 1616 Athens, TX 75752 Phone: 1-903-677-5017 Facsimile: 1-903-677-6083 Common or Usual Name: Auto Injector Classification Name: Introducer, Syringe Needle Regulation Number: 880.6920 Medical Specialty: General Hospital Product Code: KZH Device Class: Class II Predicate Devices: * Union Medico Aps.; Personal Injector (K033696), * Biogen; InvisijectTM Reusable Auto Injector (K032425), * Pharma-Pen Inc.; ConfiDose Auto-Injector (K042557). Intended Use: The ConfiDoseTM IM auto-injector is a semi-automatic injection system intended to be used for the manual transfer, containment and intramuscular injection of liquid drugs biologics and under the direction of a physician. The ConfiDoseTM IM auto-injector system includes an automatic needle retraction mechanism that is intended to aid in the prevention of accidental needle sticks. The ConfiDoseTM IM auto-injector system is intended to mask needle insertion, injection and needle withdrawal from patient view. Attachment J Page 1 of 2 Technological Characteristics and Substantial Equivalence: ) A' ) The ConfiDoseTM IM auto-injector consists of a syringe cartridge with prefixed needle, power pack housing with spring loaded mechanism to insert a hypodermic needle into a patient to predetermined depth below the skin surface and a window tube with spring- loaded retraction mechanism. -

Development of Oral Disintegrating Tablet of Rizatriptan Benzoate with Inhibited Bitter Taste

American-Eurasian Journal of Scientific Research 7 (2): 47-57, 2012 ISSN 1818-6785 © IDOSI Publications, 2012 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.aejsr.2012.7.2.1507 Development of Oral Disintegrating Tablet of Rizatriptan Benzoate with Inhibited Bitter Taste 1Alpana P. Kulkarni, 22Amol B. Khedkar, Swaroop R. Lahotib and 2M.H.D. Dehghanb 1Department of Quality Assurance, Dr. Maulana Azad Educational Trust's Y.B. Chavan, College of Pharmacy, Rauza Bagh, Aurangabad- 431001, Maharashtra, India 2Department of Pharmaceutics, Dr. Maulana Azad Educational Trust's Y.B. Chavan, College of Pharmacy, Rauza Bagh, Aurangabad- 431001, Maharashtra, India Abstract: The purpose of this research was to mask the bitter taste of Rizatriptan benzoate (RB) and to formulate an oral disintegrating tablet (ODT) of the taste-masked drug. Taste masking was done by mass extrusion with aminoalkylmethacrylate copolymer, Eudragit EPO, in different ratios. The drug: polymer ratio was optimized based on bitterness score and RB -polymer interaction. Taste masking was evaluated by checking the in vitro release of RB in simulated salivary fluid (SSF) of pH 6.8 and by sensory evaluation in human volunteers. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FTIR) and Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) were performed to identify the physicochemical interaction between RB and the polymer. For formulation of rapid- disintegrating tablets of RB, the batch that depicted optimum release of RB in SSF, was considered. ODTs of Rizatriptan Benzoate were prepared by using superdisintegrants namely, sodium starch glycolate, crospovidone and croscarmellose sodium using the direct compression method. The tablets were evaluated for hardness, friability, wetting time, in vitro disintegration time. The optimum formulation was selected and the tablets were evaluated for thickness, drug content, content uniformity and mouth feel, in vivo disintegration time, in vitro drug release at pH 1.2 and 6.8 and stability study.