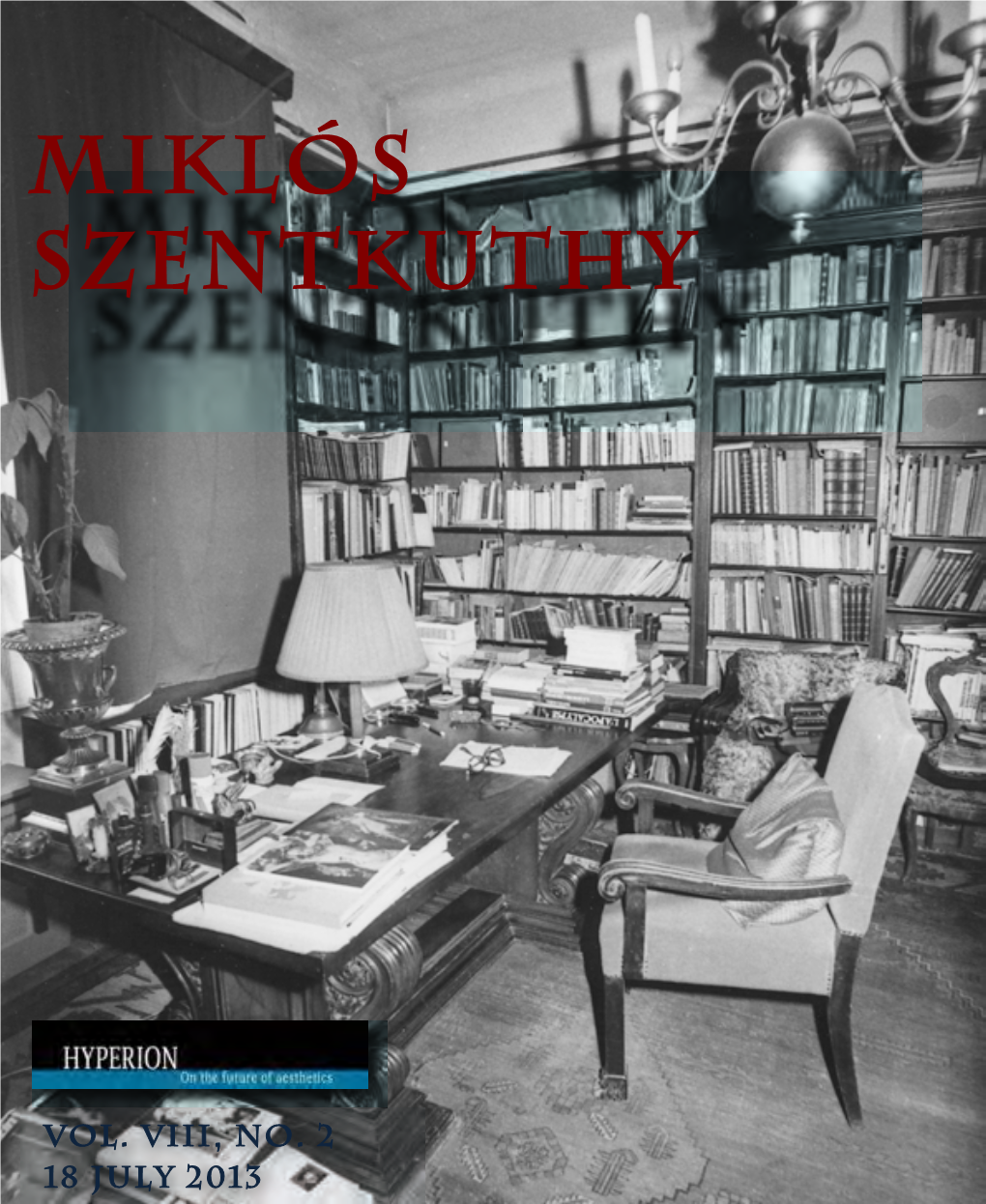

Miklós Szentkuthy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

23. Juli 2021 - 01

23. Juli 2021 - 01. August 2021 Freitag, 23. Juli 2021 Samstag, 31. Juli 2021 12.00 Uhr Lungau Open 2021 "Österr. Staatsmeisterschaft Paragleiten" 10.30 Uhr Bergmesse der Dorfgemeinschaft Lintsching Treffpunkt: Gipfelkreuz Ersatztermin 29.07.-01.08.2021 - St. Michael, St. Martin - Landeplatz Bei Schlechtwetter findet die Veranstaltung nicht statt! 3-G Regel beachten! 12.30 Uhr Volldampfwochenende Zusätzlicher Dampfzug nach Mariapfarr mit 30 Minuten St. Andrä, Schareck Aufenthalt. - Mauterndorf, Bahnhof 15.00 Uhr Volldampfwochenende Zusätzlicher Dampfzug nach Mariapfarr mit 30 Minuten Tägliche Veranstaltungen Aufenthalt. - Mauterndorf, Bahnhof 18.00 Uhr Orchesterkonzert der Streicherwoche 09.00 Uhr Liftbetrieb der Grosseckbahn Mauterndorf geöffnet bis 16:30 Uhr Weißpriach - Mariapfarr, Wallfahrtsbasilika Mariapfarr Mauterndorf, Grosseck Speiereck 19.30 Uhr Musiktheater: Schattseitenkinder mit Querschläger & Mokrit 09.30 Uhr Rafting auf der Mur Voranmeldung: T +43 (0)664 4228083 Eintritt € 20,-- - St. Michael, Alte Glashütte Mauterndorf, Flugplatz 10.00-18.00 Uhr Burgerlebnis - Lust auf Mittelalter? - Mauterndorf, Burg Samstag, 24. Juli 2021 10.00-18.00 Uhr Erlebnisausstellung (M)ursprung - Natur im Fluss Eintritt frei! 12.00 Uhr Lungau Open 2021 "Österr. Staatsmeisterschaft Paragleiten" Muhr, Ortszentrum Ersatztermin 29.07.-01.08.2021 - St. Michael, St. Martin - Landeplatz 12.30 Uhr Volldampfwochenende Zusätzlicher Dampfzug nach Mariapfarr mit 30 Minuten Wöchentliche Veranstaltungen Aufenthalt. - Mauterndorf, Bahnhof 15.00 Uhr Volldampfwochenende -

Saint Alexius

Saint Alexius SAINT OF THE DAY 17-07-2021 Saint Alexius of Rome (4th-5th centuries) has been over the centuries a source of inspiration for men of letters and artists. Over time, various hagiographic versions of his figure have emerged, united by a fundamental trait: his renunciation of everything in order to follow God, obtaining the hundredfold promised by Jesus. His life is known through three traditions, one Syriac, one Greek and one Latin. The Syriac version, dating back to the end of the 5th century, is the oldest. It tells of a rich young man originally from Constantinople, the “New Rome”, who secretly boarded a ship the night before his wedding and reached Syria. That young man then continued on his way to Edessa (in what is now southern Turkey), a city with a large Christian community that for centuries guarded the Mandylion, a cloth bearing the Face of Jesus and identified by several scholars with the Shroud of Turin. There he lived begging for alms and in the evening he distributed to the poor what he had collected during the day, keeping for himself only the bare minimum to survive. Prayer and penance filled his days and because of his asceticism, the people called him Mar Riscia, that is “man of God”. After 17 years spent in Edessa, feeling close to the moment of death, he revealed that he belonged to a noble Roman family and had renounced marriage to consecrate himself to God. According to this ancient hagiography his death occurred while the Syrian writer Rabbula was Bishop of Edessa (c. -

Pdf-61-Gzp-Unternberg-Tb.Pdf

Verfasser: Hydroconsult GmbH 8045 Graz, St. Veiterstraße 11a Tel.: 0316 694777-0 Bearbeitung: Dipl. Ing. Dr. Bernhard J. Sackl Dipl. Ing. Ulrike Savora GZ: 070703 Graz, Dezember 2007 GEFAHRENZONENAUSWEISUNG LUNGAU 1 Hydroconsult GmbH 1. EINLEITUNG................................................................................... 3 1.1. Bezeichnung des Projektes.................................................................. 3 1.2. Ortsangabe ............................................................................................ 3 1.2.1. Untersuchungsbereich Niederschlag-Abfluss-Modell.............................. 3 1.2.2. Untersuchungsbereich 2d-Abflussuntersuchung..................................... 4 1.3. Verwendete Unterlagen ........................................................................ 4 2. RECHTLICHE GRUNDLAGEN....................................................... 5 2.1. Richtlinien zur Gefahrenzonenausweisung........................................ 5 2.1.1. Ausweisungsgrundsätze ......................................................................... 5 2.1.2. Kriterien für die Zonenabgrenzung.......................................................... 6 2.1.3. Prüfung der Gefahrenzonenpläne ........................................................... 7 2.1.4. Revision der Gefahrenzonenpläne.......................................................... 8 2.2. Wasserbautenförderungsgesetz.......................................................... 8 3. ERGEBNISSE AUS GEK MUR UND GEK TAURACH-LONKA.... 8 3.1. Einleitung.............................................................................................. -

Ein Auszug Tipps Für Interessante & Erholsame Zwischens

Kurort Mariapfarr - dem sonnenreichsten Ort Österreichs. Von Mariapfarr gelangt Entlang 01 Mitterbergrunde, 02 Schwarzenbergrunde & 46 Pochwerk & Hochofen Kendlbruck Entlang 10 Route Lessach Genussradeln im Salzburger Lungau man über das Stockerfeld zur Taurach und entlang der Taurachbahn zurück nach Besonderheiten entlang des Murradweges Direkt neben der Bundesstraße ist das „Pochwerk“. Das vorher geröstete Silbererz St. Andrä. 03 Murradweg Der Salzburger Lungau - ein sonnenreiches Höhenbecken auf über 1.000 m Seehöhe - wurde in diesen Anlagen gepocht (zerkleinert) bis auf Haselnussgröße oder sogar noch 59 Burgruine Thurnschall Kulturradweg - Das Brauchtumsjahr in Unternberg ist ein Eldorado für alle Genussradfahrer. 10 feiner. Die Anlage war bis 1782 in Betrieb. Route Lessach UNTERNBERG Etwa um 1200 gegründet - wird die Burg und das gesamte Gebiet Lessach 1242 Auf den Rastplätzen entlang des Murradweges, der Mitterbergrunde und der Die Schwierigkeitsstufen der einzelnen Strecken sind wie folgt markiert: Der Hochofen: Die Schmelzanlage besteht aus einem Floßofen und zwei Feuern in einer ca. 28 km, ca. 250 Hm, max. 7% Steigung, Ausgangspunkt Tamsweg 33 Naherholungsgebiet Unternberg an den Salzburger Erzbischof verkauft. Bei archäologischen Grabungen im Jahr Schwarzenbergroute durch Unternberg hat die Landjugendgruppe mit Skulptu- leicht mittel schwer 19 m hohen, kaminartigen Esse. ren und Figuren aus Holz, Metall und anderen natürlichen Stoffen das örtliche • • • Von Tamsweg geht’s entlang der Mitterbergrunde nach Wölting, weiter entlang des 2001 wurden die ca. 8 m hohen Reste des Wehrturms, sowie bis zu 4 m dicke Direkt am flachen Murufer zwischen den Ortsteilen Illmitzen und Neggerndorf laden Kann jederzeit besichtigt werden, Sonderführungen auf Anfrage. Brauchtum dargestellt. Auf Informationstafeln werden alle dargestellten Bräuche Lessachbaches, vorbei an alten Bauernhäusern erreicht man das schöne Dorf Umfassungsmauern freigelegt. -

Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (Ca

Conversion and Empire: Byzantine Missionaries, Foreign Rulers, and Christian Narratives (ca. 300-900) by Alexander Borislavov Angelov A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (History) in The University of Michigan 2011 Doctoral Committee: Professor John V.A. Fine, Jr., Chair Professor Emeritus H. Don Cameron Professor Paul Christopher Johnson Professor Raymond H. Van Dam Associate Professor Diane Owen Hughes © Alexander Borislavov Angelov 2011 To my mother Irina with all my love and gratitude ii Acknowledgements To put in words deepest feelings of gratitude to so many people and for so many things is to reflect on various encounters and influences. In a sense, it is to sketch out a singular narrative but of many personal “conversions.” So now, being here, I am looking back, and it all seems so clear and obvious. But, it is the historian in me that realizes best the numerous situations, emotions, and dilemmas that brought me where I am. I feel so profoundly thankful for a journey that even I, obsessed with planning, could not have fully anticipated. In a final analysis, as my dissertation grew so did I, but neither could have become better without the presence of the people or the institutions that I feel so fortunate to be able to acknowledge here. At the University of Michigan, I first thank my mentor John Fine for his tremendous academic support over the years, for his friendship always present when most needed, and for best illustrating to me how true knowledge does in fact produce better humanity. -

Effective Firefighting Operations in Road Tunnels

Effective Firefighting Operations in Road Tunnels Hak Kuen Kim, Anders Lönnermark and Haukur Ingason SP Technical Research Institute of Sweden Fire Technology SP Report 2010:10 Effective Firefighting Operations in Road Tunnels Hak Kuen Kim, Anders Lönnermark and Haukur Ingason The photo on the front page was provided by Anders Bergqvist at the Greater Stockholm Fire Brigade. 2 3 Abstract The main purpose of this study is to develop operational procedures for fire brigades in road tunnels. Although much progress has been achieved in various fields of fire safety in tunnels, very little attention has been paid specifically to fire fighting in tunnels. This study is focused on obtaining more information concerning how effectively the fire brigade can fight road tunnel fires and what limitations and threats fire brigades may be faced with. This knowledge can help parties involved in tunnel safety to understand safety issues and enhance the level of fire safety in road tunnels. The report is divided into three main parts. The first part consists of a review of relevant studies and experiments concerning various key parameters for fire safety and emergency procedures. The history of road tunnel fires is then summarised and analyzed. Among all road tunnel fires, three catastrophic tunnel fires are highlighted, focusing on the activities of fire brigades and the operation of technical fire safety facilities. In the second part specific firefighting operations are developed. This has been based on previous experience and new findings from experiments performed in the study. In the last part, information is given on how the proposed firefighting operations can be applied to the management of fire safety for road tunnels. -

Der Abrahamhof Aus Unterweißburg Bei St. Michael Im Lungau Im Salzburger Freilichtmuseum

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Mitt(h)eilungen der Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde Jahr/Year: 2000 Band/Volume: 140 Autor(en)/Author(s): Rebernig-Ahamer Regine Artikel/Article: Der Abrahamhof aus Unterweißburg bei St. Michael im Lungau im Salzburger Freilichtmuseum. 331-360 © Gesellschaft für Salzburger Landeskunde, Salzburg, Austria; download unter www.zobodat.at 331 Der Abrahamhof aus Unterweißburg bei St. Michael im Lungau im Salzburger Freilichtmuseum Von Regine R ebernig-A ham er Einleitung Am 3. April 1989 konnte das Salzburger Freilichtmuseum den Lungauer Einhof „Abraham“ erwerben. Der breit hingelagerte, zum Großteil steinge mauerte Hof stand im Weiler Unterweißburg, Gemeinde St. Michael/Lungau (Seehöhe 1020 m); die ehemalige Straße von Zederhaus Richtung Muhr führ te am Haus vorbei. Der Abraham gilt als Hof mittlerer Größe, dessen Wiesen und Felder weit verstreut, jedoch am Talboden liegen. In einer relativ langen Bauzeit, von 1990 bis 1994, wurde der Hof im Be reich „Lungau“ des Museumsgeländes wieder aufgebaut. Wie bei den anderen Museumsgebäuden wurde auch hier versucht, die nächste Umgebung des Hofs möglichst originalgetreu zu gestalten: Ähnlich der Situation in Unter weißburg wurde dem Haus ein hölzerner, eingeschossiger Getreidekasten bei gestellt, Garten und Zäune wurden nach einem Foto aus der Zeit um 1910 (siehe Abb. S. 341) rekonstruiert, und in einiger Entfernung wurde ein zwei ter, jedoch gemauerter Getreidekasten — nach einem Vorbild aus dem be nachbarten Oberweißburg — errichtet. Am wiedererrichteten Hof werden ganz bewusst verschiedene Situationen in der Geschichte der Entwicklung bzw. Veränderung des Gebäudes darge stellt: Die Fassade zeigt die Gestaltungen von Beginn und Ende des 19. -

MONTAG-FREITAG (SCHULE) LINIE Zederhaus Moserbrücke Ab

270 700 710 Zederhaus - St. Michael - Tamsweg Frühjahrs- und Herbstfahrplan 2020 - gültig von 20.04. bis 10.07.2020 und ab 14.09. bis 27.11.2020 MONTAG-FREITAG (SCHULE) MO-FR (FERIEN) SAMSTAG LINIE 700 710 270 700 700 270 700 700 Zederhaus Moserbrücke ab 06:23 06:30 08:53 13:53 06:23 08:53 06:23 08:53 Zederhaus Königbauernweg 06:24 06:31 08:54 13:54 06:24 08:54 06:24 08:54 Zederhaus Sportplatz 06:26 06:33 08:55 13:56 06:26 08:55 06:26 08:56 Zederhaus Feuerwehr 06:27 06:34 08:56 13:57 06:27 08:56 06:27 08:57 Zederhaus Ortsmitte 06:28 06:35 08:57 13:58 06:28 08:57 06:28 08:58 Zederhaus Lagerhaus 06:29 06:36 08:58 13:59 06:29 08:58 06:29 08:59 Zederhaus Mosthandlung 06:30 06:37 08:59 14:00 06:30 08:59 06:30 09:00 Zederhaus Lenzlbrücke 06:31 06:38 09:00 14:01 06:31 09:00 06:31 09:01 Zederhaus Tafernwirt 06:33 06:40 09:01 14:02 06:33 09:01 06:33 09:02 Zederhaus Mooshäusl 06:34 06:41 09:02 14:03 06:34 09:02 06:34 09:03 Zederhaus Krottendorfer 06:35 06:42 09:03 14:04 06:35 09:03 06:35 09:04 St. Michael i.L. Fell/Blasiwirt 06:37 06:44 09:04 14:05 06:37 09:04 06:37 09:05 St. -

The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople During the Frankish Era (1196-1303)

The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the Frankish Era (1196-1303) ELENA KAFFA A thesis submitted to the University of Wales In candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Archaeology University of Wales, Cardiff 2008 The Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the Frankish Era (1196-1303) ELENA KAFFA A thesis submitted to the University of Wales In candidature for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy School of History and Archaeology University of Wales, Cardiff 2008 UMI Number: U585150 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Dissertation Publishing UMI U585150 Published by ProQuest LLC 2013. Copyright in the Dissertation held by the Author. Microform Edition © ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, Ml 48106-1346 ABSTRACT This thesis provides an analytical presentation of the situation of the Greek Church of Cyprus, the Morea and Constantinople during the earlier part of the Frankish Era (1196 - 1303). It examines the establishment of the Latin Church in Constantinople, Cyprus and Achaea and it attempts to answer questions relating to the reactions of the Greek Church to the Latin conquests. -

And Ninth-Century Rome: the Patrocinia of Diaconiae, Xenodochia, and Greek Monasteries*

FOREIGN SAINTS AT HOME IN EIGHTH- AND NINTH-CENTURY ROME: THE PATROCINIA OF DIACONIAE, XENODOCHIA, AND GREEK MONASTERIES* Maya Maskarinec Rome, by the 9th century, housed well over a hundred churches, oratories, monasteries and other religious establishments.1 A substantial number of these intramural foundations were dedicated to “foreign” saints, that is, saints who were associated, by their liturgical commemoration, with locations outside Rome.2 Many of these foundations were linked to, or promoted by Rome’s immigrant population or travelers. Early medieval Rome continued to be well connected with the wider Mediterranean world; in particular, it boasted a lively Greek-speaking population.3 This paper investigates the correlation between “foreign” institutions and “foreign” cults in early medieval Rome, arguing that the cults of foreign saints served to differentiate these communities, marking them out as distinct units in Rome, while at the same time helping integrate them into Rome’s sacred topography.4 To do so, the paper first presents a brief overview of Rome’s religious institutions associated with eastern influence and foreigners. It * This article is based on research conducted for my doctoral dissertation (in progress) entitled “Building Rome Saint by Saint: Sanctity from Abroad at Home in the City (6th-9th century).” 1 An overview of the existing religious foundations in Rome is provided by the so-called “Catalogue of 807,” which I discuss below. For a recent overview, see Roberto Meneghini, Riccardo Santangeli Valenzani, and Elisabetta Bianchi, Roma nell'altomedioevo: topografia e urbanistica della città dal V al X secolo (Rome: Istituto poligrafico e zecca dello stato, 2004) (hereafter Meneghini, Santangeli Valenzani, and Bianchi, Roma nell'altomedioevo). -

Greek Cultures, Traditions and People

GREEK CULTURES, TRADITIONS AND PEOPLE Paschalis Nikolaou – Fulbright Fellow Greece ◦ What is ‘culture’? “Culture is the characteristics and knowledge of a particular group of people, encompassing language, religion, cuisine, social habits, music and arts […] The word "culture" derives from a French term, which in turn derives from the Latin "colere," which means to tend to the earth and Some grow, or cultivation and nurture. […] The term "Western culture" has come to define the culture of European countries as well as those that definitions have been heavily influenced by European immigration, such as the United States […] Western culture has its roots in the Classical Period of …when, to define, is to the Greco-Roman era and the rise of Christianity in the 14th century.” realise connections and significant overlap ◦ What do we mean by ‘tradition’? ◦ 1a: an inherited, established, or customary pattern of thought, action, or behavior (such as a religious practice or a social custom) ◦ b: a belief or story or a body of beliefs or stories relating to the past that are commonly accepted as historical though not verifiable … ◦ 2: the handing down of information, beliefs, and customs by word of mouth or by example from one generation to another without written instruction ◦ 3: cultural continuity in social attitudes, customs, and institutions ◦ 4: characteristic manner, method, or style in the best liberal tradition GREECE: ANCIENT AND MODERN What we consider ancient Greece was one of the main classical The Modern Greek State was founded in 1830, following the civilizations, making important contributions to philosophy, mathematics, revolutionary war against the Ottoman Turks, which started in astronomy, and medicine. -

Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past

UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings W A S H I N G T O N , D. C. Hungary and the Holocaust Confrontation with the Past Symposium Proceedings CENTER FOR ADVANCED HOLOCAUST STUDIES UNITED STATES HOLOCAUST MEMORIAL MUSEUM 2001 The assertions, opinions, and conclusions in this occasional paper are those of the authors. They do not necessarily reflect those of the United States Holocaust Memorial Council or of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Third printing, March 2004 Copyright © 2001 by Rabbi Laszlo Berkowits, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Randolph L. Braham, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Tim Cole, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by István Deák, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Eva Hevesi Ehrlich, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Charles Fenyvesi; Copyright © 2001 by Paul Hanebrink, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by Albert Lichtmann, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum; Copyright © 2001 by George S. Pick, assigned to the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum In Charles Fenyvesi's contribution “The World that Was Lost,” four stanzas from Czeslaw Milosz's poem “Dedication” are reprinted with the permission of the author. Contents