The Art of Medieval Hungary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

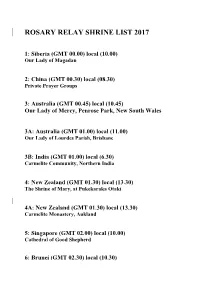

Rosary Relay Shrine List 2017

ROSARY RELAY SHRINE LIST 2017 1: Siberia (GMT 00.00) local (10.00) Our Lady of Magadan 2: China (GMT 00.30) local (08.30) Private Prayer Groups 3: Australia (GMT 00.45) local (10.45) Our Lady of Mercy, Penrose Park, New South Wales 3A: Australia (GMT 01.00) local (11.00) Our Lady of Lourdes Parish, Brisbane 3B: India (GMT 01.00) local (6.30) Carmelite Community, Northern India 4: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) The Shrine of Mary, at Pukekaraka Otaki 4A: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) Carmelite Monastery, Aukland 5: Singapore (GMT 02.00) local (10.00) Cathedral of Good Shepherd 6: Brunei (GMT 02.30) local (10.30) Church of Our Lady’s Assumption 6A: Vietnam (GMT 02.45) local (09.45) Our Lady of La Vang 7: Philippines (GMT 03.00) local (11.00). The National Shrine of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish, New Manila, Quezon City 8: Philippines (GMT 03.30) local (11.30) Shrine of the Immaculate Conception, Manila 9: Philippines (GMT 04.00) local (12.00) Our Lady of Manaoag 10: Sri Lanka (GMT 04.30) local (10.00) Shrine of Our Lady of Matara 11: India (GMT 05.00) local (10.30) Shrine of Our Lady of Health, Velankanni 12: Malta (GMT 05.30) local (07.30) Our Lady of Mellieha 13: UAE (GMT 06.00) local (10.00) The Church of St Mary, Dubai 14: Lebanon (GMT 06.30) local (09.30) Our Lady of Lebanon. Harissa 15: Holy Land (GMT 07.00) local (10.00) International Center of Mary of Nazareth. -

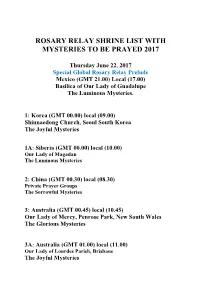

Rosary Relay Shrine List with Mysteries to Be Prayed 2017

ROSARY RELAY SHRINE LIST WITH MYSTERIES TO BE PRAYED 2017 Thursday June 22, 2017 Special Global Rosary Relay Prelude Mexico (GMT 21.00) Local (17.00) Basilica of Our Lady of Guadalupe The Luminous Mysteries. 1: Korea (GMT 00.00) local (09.00) Shinnaedong Church, Seoul South Korea The Joyful Mysteries 1A: Siberia (GMT 00.00) local (10.00) Our Lady of Magadan The Luminous Mysteries 2: China (GMT 00.30) local (08.30) Private Prayer Groups The Sorrowful Mysteries 3: Australia (GMT 00.45) local (10.45) Our Lady of Mercy, Penrose Park, New South Wales The Glorious Mysteries 3A: Australia (GMT 01.00) local (11.00) Our Lady of Lourdes Parish, Brisbane The Joyful Mysteries 3B: India (GMT 01.00) local (6.30) Carmelite Community, Northern India The Luminous Mysteries 4: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) The Shrine of Mary, at Pukekaraka Otaki The Sorrowful Mysteries 4A: New Zealand (GMT 01.30) local (13.30) Carmelite Monastery, Aukland The Glorious Mysteries 4B: Thailand (01.45) local (8.45) St. Raphael Kalinowski Carmelite Priory Chapel of the Infant Jesus in Sampran. Glorious Mysteries 5: Singapore (GMT 02.00) local (10.00) Good Shepherd Convent Chapel The Joyful Mysteries 6: Brunei (GMT 02.30) local (10.30) Church of Our Lady’s Assumption The Luminous Mysteries 6A: Vietnam (GMT 02.45) local (09.45) Our Lady of La Vang The Sorrowful Mysteries 7: Philippines (GMT 03.00) local (11.00). The National Shrine of Our Lady of Mount Carmel Parish, New Manila, Quezon City The Glorious Mysteries 8: Philippines (GMT 03.30) local (11.30) Shrine of the -

European Race Audit

EUROPEAN RACE AUDIT BRIEFING PAPER NO.5 - SEPTEMBER 2011 Breivik, the conspiracy theory and the Oslo massacre Contents (1) The conspiracy theory and the Oslo massacre 1 (2) Appendix 1: Responses to the Oslo massacre 14 (3) Appendix 2: Documentation of anti-Muslim violence and other related provocations, Autumn 2010-Summer 2011 18 In a closed court hearing on 25 July 2011, 32-year-old But, as this Briefing Paper demonstrates, the myths that Anders Behring Breivik admitted killing seventy-seven Muslims, supported by liberals, cultural relativists and people on 22 July in two successive attacks in and Marxists, are out to Islamicise Europe and that there is a around the Norwegian capital – the first on government conspiracy to impose multiculturalism on the continent buildings in central Oslo, the second on the tiny island of and destroy western civilisation, are peddled each day Utøya, thirty-eight kilometres from Oslo. But he denied on the internet, in extreme-right, counter-jihadist and criminal responsibility, on the basis that the shooting neo-Nazi circles. In this Briefing Paper we also examine spree on the Norwegian Labour Party summer youth certain intellectual currents within neoconservativism camp, which claimed sixty-nine lives, was necessary to and cultural conservatism. For while we readily admit wipe out the next generation of Labour Party leaders in that these intellectual currents do not support the order to stop the further disintegration of Nordic culture notion of a deliberate conspiracy to Islamicise Europe, from the mass immigration of Muslims, and kick start a they are often used by conspiracy theorists to underline revolution to halt the spread of Islam. -

Lake Resorts & Spas

THE BEST OF AUSTRIA 1 rom soaring alpine peaks in the west to the seem- ingly endless valleys and lowlands in the east, Aus- Ftria’s natural beauty is breathtaking. For over a millennium the region has been at the center of European history and culture. Its lively historic cities, like the capital Vienna, Graz, Innsbruck, and Salzburg are as aesthetically pleasing as their dramatic settings. In summer, Austria’s lakes, rivers, and hiking paths come to life, while the winter months are interwoven with hot-spiced wine and ski excursions. The Austrians are elegant and cultured people with a dark, yet resilient sense of humor and a knack for fashioning lifestyle to fit their needs. From 5th generation country farmers to middle class city dwellers to members of the faded aristocracy, sophistication, beauty, and good food are of the utmost importance. For such a small country, Austria has made more than its fair share of global impact. Besides exports like Linzer Torte, Manner wafers, and Red Bull, Vienna is the third UN headquarters’ city, along with New York and Geneva. With some 17,000 diplomats in residence and conveniently located at the crossroads of eastern and western Europe, Austria has the highest density of foreign intelligence agents in the world. Once the seat of the Austro-Hungarian Empire, today’s Austrian capital Vienna is a bustling metropolis with a strong commitment to the good life, and the city is consistently ranked number 1 in quality of life worldwide. Throughout this book, you’ll find Austria’s choice sights, restaurants, and hotels, and this chapter gives you a glimpse of the very best. -

364.Gyorsárverés Numizmatika

Gyorsárverés 364. numizmatika Az árverés anyaga megtekinthető weboldalunkon és irodánkban (VI. Andrássy út 16. III. emelet. Nyitva tartás: H-Sz: 10-17, Cs: 10-19 óráig, P: Zárva) 2020. 17-20-ig. AJÁNLATTÉTELI HATÁRIDŐ: 2020. február 20. 19 óra. Ajánlatokat elfogadunk írásban, személyesen, vagy postai úton, telefonon a 317-4757, 266-4154 számokon, faxon a 318-4035 számon, e-mailben az [email protected], illetve honlapunkon (darabanth.com), ahol online ajánlatot tehet. ÍRÁSBELI (fax, email) ÉS TELEFONOS AJÁNLATOKAT 18:30-IG VÁRUNK. A megvásárolt tételek átvehetők 2020. február 24-én 10 órától. Utólagos eladás február 27-ig. (Nyitvatartási időn kívül honlapunkon vásárolhat a megmaradt tételekből.) Anyagbeadási határidő a 365. gyorsárverésre: február 20. Az árverés FILATÉLIA, NUMIZMATIKA, KÉPESLAP és az EGYÉB GYŰJTÉSI TERÜLETEK tételei külön katalógusokban szerepelnek! A vásárlói jutalék 22% Részletes árverési szabályzat weboldalunkon és irodánkban megtekinthető darabanth.com Tisztelt Ügyfelünk! 33., tavaszi nagyaukciónkra már várjuk a beadásokat, március végéig! 364. aukció: Megtekintés: február 17-20-ig! Tételek átvétele: február 24. 10 órától 363. aukció elszámolás: február 25-től! Amennyiben átutalással kéri az elszámolását, kérjük jelezze e-mailben, vagy telefonon. Kérjük az elszámoláshoz a tétel átvételi listát szíveskedjenek elhozni! Kezelési költség 240 Ft / tétel / árverés. A 2. indításnál 120 Ft A vásárlói jutalék 22% Tartalomjegyzék: Numizmatikai kellékek 30000-30015 Numizmatikai irodalom 30016-30027 Numizmatikával kapcsolatos -

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2016 Issue # 435

SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2016 Issue # 435 Principles and Values of the European Union The stamps shown above, is- That such a message is timely sued by the Republic of CYPRUS goes without saying. After on 18 June 2016, were devel- Brexit there is much concern as oped in cooperation with the to where Europe is heading. As European Parliament, Ministry of I write this there has been Culture and the Cypriot Post Of- more terrorist activity and con- fice. The motifs suggest Peace, cerns over immigration policy. Justice and Solidarity. Economic uncertainty will Your humble editor concedes probably continue worldwide the artistic merit, which was the for some time, while the USA result of a contest among faces what is perhaps the most schoolchildren, but without ad- momentous election in dec- ditional wording it’s not immedi- ades. ately clear, at least to me, exactly “May you live in interesting times.” what the message is. — ancient Chinese curse SEPTEMBER-OCTOBER 2016 435-2 v = value(s) ms= mini-sheet New Issues ss = souvenir sheet Europa 2016 "Ecology in Europe - Think Green" ALBANIA 1v printed in ms of 9 HUNGARY 1v printed in ms of 4 (shown) Issue date 9 July 2016 Issue date 6 May 2016 No Issues: STILL TO GO GREAT BRITAIN ISLE OF MAN GREENLAND ARMENIA RUSSIA GEORGIA TURKEY KAZAKHSTAN sepac 2016 “Seasons” LUXEMBOURG 1v JERSEY 1v GIBRALTAR 1v Issue date 13 September 2016 Issue date 4 November 2016 Issue date 25 July 2016 (Tentative) ICELAND 1v from a set of 4 Part of a set of 5 stamps com- This preview image is taken from memorating the 200th anniver- (shown) printed in ms of 10 self- the sepac competition website adhesive stamps sary of the Alameda Gardens Issue date 28 April 2016 From Iceland Post: “The seasons constitute the SEPAC theme this year. -

Between Austria and Germany, Heimat and Zuhause: German-Speaking Refugees and the Politics of Memory in Austria

BETWEEN AUSTRIA AND GERMANY, HEIMAT AND ZUHAUSE: GERMAN-SPEAKING REFUGEES AND THE POLITICS OF MEMORY IN AUSTRIA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in German By Joshua Alexander Seale, M.A. Washington, D.C. August 14, 2020 Copyright 2020 by Joshua Alexander Seale All Rights Reserved ii BETWEEN AUSTRIA AND GERMANY, HEIMAT AND ZUHAUSE: GERMAN-SPEAKING REFUGEES AND THE POLITICS OF MEMORY IN AUSTRIA Joshua Alexander Seale, M.A. Dissertation Advisor: Friederike Ursula Eigler, Ph.D. ABSTRACT This dissertation explores the memory of postwar German-speaking refugees in Austria through an analysis of diverse media, cultural practices, and their reception. Part I of the dissertation examines postwar memorials and their reception in newspapers, as well as the role of pilgrimage, religious ritual, and public responses of defacement. Part II focuses on post-Waldheim literature and its reception, specifically examining the literary genres of novels and travelogues describing German-speaking refugees’ trips to their former homes. In examining these memorials and literature as well as their reception, I show how static and marginalized the memory of German- speaking refugees has remained throughout the history of the Second Republic, even after the fragmentation of Austrian memory in the wake of the Waldheim affair. While Chapter 1 posits four reasons for this marginalization, the continuance of this marginalization into the present can be summed up by drawing on Oliver Marchart’s concept of historical-political memory and by pointing to the politicization and tabooization of the memory as a far-right discourse. -

Vladislaus Henry East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450

Vladislaus Henry East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450 General Editor Florin Curta VOLUME 33 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ecee Vladislaus Henry The Formation of Moravian Identity By Martin Wihoda Translated by Kateřina Millerová LEIDEN | BOSTON Cover illustration: Between 1213 and 1222, Vladislaus Henry used a single type of equestrian seal. Although he entered the public life as a margrave of Moravia, his shield bore the sign of a lion, which also appeared in the coat of arms of his brother, King of Bohemia Přemysl Otakar I. Photography by MZA (Moravian Land Archives) Brno. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Wihoda, Martin, 1967- Vladislaus Henry : the formation of Moravian identity / by Martin Wihoda ; translated by Katerina Millerova. pages cm. — (East Central and Eastern Europe in the Middle Ages, 450–1450, ISSN 1872-8103; volume 33) Includes bibliographical references and index. ISBN 978-90-04-25049-9 (hardback : acid-free paper) — ISBN 978-90-04-30383-6 (e-book) 1. Vladislav Jindrich, Margrave of Moravia, approximately 1167–1222. 2. Moravia (Czech Republic)—Kings and rulers—Biography. 3. Moravia (Czech Republic)—Politics and government. 4. Premysl Otakar I, King of Bohemia, approximately 1165–1230 5. Group identity—Czech Republic—Moravia—History—To 1500. 6. Community life—Czech Republic—Moravia—History—To 1500. 7. Land tenure—Political aspects— Czech Republic—Moravia—History—To 1500. 8. Social change—Czech Republic—Moravia—History— To 1500. 9. Moravia (Czech Republic)—History—To 1526. 10. Bohemia (Czech Republic)—History—To 1526. I. Title. DB2091.V52W44 2015 943.72’0223092—dc23 [B] 2015027400 This publication has been typeset in the multilingual ‘Brill’ typeface. -

Austria, Germany & Medjugorje

J OIN S T. M ARK C HURCH ON A P ILGRIMAGE TO ... St. Stephens Cathedral, Vienna Salzburg, Austria AUSTRIA, GERMANY & MEDJUGORJE September 23 - October 7, 2019 $5,999 per person from Tampa, FL www.pilgrimages.com/stmarkchurch MEDJUGORJE ONLY: September 29 - October 7, 2019| $2,994 pp from Tampa, FL Optional Post stay in Dubrovnik: October 7 - 8, 2019 | Additional $159 pp all prices are per person, based on double occupancy) ( GROUP LEADER / PARISHIONER: MARY SEAMAN Visionary: Ivan Dragicevic Medjugorje SAMPLE DAY BY DAY ITINERARY Day 1 : Monday, September 23 | Depart Tampa and for more than 500 years the most significant place of Depart Tampa & board a transatlantic flight to Frankfurt. Dinner pilgrimage in Germany in veneration of the Virgin Mary. While will be served on board. Our spiritual director from St. Mark will there, you will have the opportunity to see the Basilica, St. Kon- be with us throughout the tour and will provide daily mass at rad’s Monastery and more. Continue towards Mondsee and each location. check into our 5* hotel Bristol upon arrival in Salzburg. Day 2 : Tuesday, September 24 | Frankfurt - Rothernburg ob der Day 5: Friday, September 27 | Salzburg - Sound of Music Tour - Tauber Salzburg Upon arrival in Frankfurt you will be greeted by your tour escort/ After breakfast, we enjoy a day trip to explore Salzburg & the driver and will be escorted to your transportation to the nearby picturesque Salzkammergut Region for a guided tour of its town of Rothenburg which means “Red Fortress above the narrow streets and secluded passageways. The heritage of the Tauber” in the region of Bavaria Germany. -

Mariazeller Land Mariazeller Land Mariazeller Land ...Rich in Faith ...Rich in Summer Fun ...Rich in Runs

Mariazeller land Mariazeller land Mariazeller Land ...rich in Faith ...rich in Summer Fun ...rich in Runs On arriving in Mariazell, visitors are amazed by the wide range of languages, peoples Mariazeller Land is wonderful in the summertime with all its walking and hiking trails On the two skiing mountains in Mariazeller Land you have your choice of activities: and cultures they encounter. It is a town with an 850-year history and reflects the full and its large range of sports and recreational options. Mountain bikers have a diverse skiing, carving, snowboarding, or touring. Modern lifts take you to the top of superbly diversity of European life. Many generations have left their traces here, as attested to choice of trails in all directions. The route of the Alpentour Austria branches off here groomed slopes. Snow machines assure a good cover of snow from December through by the treasure chambers, votive images and streams of countless pilgrims. The holy from the Styria trail system to head towards Vienna. It also crosses the Romantic Tour March, and a free bus service operates between the two mountains. statue of the Blessed Virgin in Mariazell, known as “Magna Mater Austriae”, “Magna here. This beautiful countryside attracts beginners and experts alike. Para-gliders, Hungarorum Domina” and “Mater Gentium Slavorum”, is a beacon for people searching hang-gliders and sailplanes can take to the skies for a taste of pure freedom. Water The Mariazell Bürgeralpe (868 – 1267 meters above sea level) has a new cable-car lift for meaning in their lives. lovers can plunge into crystal clear Lake Erlauf, the outdoor pool in Mitterbach and the with panorama cars plus 4-seater chair-lifts and two rope tows that assure fun on the indoor pool in Mariazell. -

Tracing the Heroic Through Gender Tracing the Heroic Tracing Through Gender Through

8 8 HELDEN – HEROISIERUNGEN – HEROISMEN Carolin Hauck – Monika Mommertz – Andreas Schlüter – Thomas Seedorf (Eds.) Tracing the Heroic Through Gender Tracing the Heroic Tracing Through Gender Through BAND 8 Carolin Hauck – Monika Mommertz – Hauck – Monika Carolin SeedorfThomas (Eds.) – Schlüter Andreas ISBN 978-3-95650-402-0 https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956504037, am 29.09.2021, 20:09:05 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb Tracing the Heroic Through Gender Edited by Carolin Hauck – Monika Mommertz – Andreas Schlüter – Thomas Seedorf https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956504037, am 29.09.2021, 20:09:05 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb HELDEN – HEROISIERUNGEN – HEROISMEN Herausgegeben von Ronald G. Asch, Barbara Korte, Ralf von den Hoff im Auftrag des DFG-Sonderforschungsbereichs 948 an der Universität Freiburg Band 8 ERGON VERLAG https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956504037, am 29.09.2021, 20:09:05 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb Tracing the Heroic Through Gender Edited by Carolin Hauck – Monika Mommertz – Andreas Schlüter – Thomas Seedorf ERGON VERLAG https://doi.org/10.5771/9783956504037, am 29.09.2021, 20:09:05 Open Access - http://www.nomos-elibrary.de/agb Gefördert durch die Deutsche Forschungsgemeinschaft Cover: Mezzo Soprano Giuditta Pasta (1798–1865) in the title role of Gioachino Rossini’s opera Tancredi (1822), Lithograph by Cäcilie Brand, n.d. © Herzog August Bibliothek Wolfenbüttel: Portr. II 4023 (A 15982) Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.d-nb.de abrufbar. © Ergon – ein Verlag in der Nomos Verlagsgesellschaft, Baden-Baden 2018 Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. -

Catholic Pilgrimage Tours

REGISTRATION FORM TERMS AND CONDITIONS CANCELLATION FEES: Passengers not taking the Travel Insured International travel insurance need to be ORATORIAN FATHERS aware of the following cancellation fees. From day of Please reserve ________ seat(s) on: AIR TRANSPORTATION: Round-trip coach class on registration to 90 days prior to departure, there is a non- American, Delta, United or other IATA member. Meals Catholic Pilgrimage refundable administration fee of $100. The remaining A Catholic Pilgrimage Tour served in flight. cancellation fee schedule is as follows: 89-60 days = $300; 59-45 days = 50% of tour price; 44-30 days = 75% of tour with Father Ravi to Central Europe & LAND TRANSPORTATION & SERVICES: By deluxe air- price; 29-15 days = 80% of tour price; 14 days or less = conditioned motor coach with professional driver, services 100% of tour price. Medjugorje of an English-speaking Tour Director, local guides, all on a 14-day Catholic admission & entrance fees and transfers to and from RESPONSIBILITY AND LIABILITY: Pilgrimage Tours LLC international airports. Daily schedule with Mass as per acts only as an agent for hotels, transportation companies, Pilgrimage Tour to Hungary, Led by Father Ravi Dasari your itinerary, however we reserve the right to modify any sightseeing tours or any service in connection with the itinerary if circumstances deem necessary. itineraries of tour members who by acceptance thereof, Austria, the Czech Republic, acknowledge that neither Pilgrimage Tours LLC and/or its May 17 - 30, 2020 LODGING: First-class accommodations, based upon agents and suppliers shall be liable for accident, injury, Poland & Medjugorje double occupancy with limited single accommodations damage, loss, liability or expense to person or property due available at an additional charge of $700.