Michael Swango, M.D

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strange, and Ultimately Dangerous, Credentialing Scenarios Highlight the Need for Msps’ Roles to Protect the Public

Strange, and ultimately dangerous, credentialing scenarios highlight the need for MSPs’ roles to protect the public April 3, 2018 For those of you who were unable to join us at NAMSS this year, we thought you might enjoy a recap of our session regarding strange credentialing scenarios. It is true that fact can be stranger than fiction, but these situations make it very clear that the role of the MSP is critical in today’s fast-paced world. The Danger of Not Doing Your Homework We begin with a history lesson — Michael Swango. He was valedictorian of his class and awarded a National Merit scholarship. His favorite movie was “Silence of the Lambs,” and he kept a scrapbook of car wrecks. He graduated from medical school in 1983, and during that time, five of the patients he cared for died. He obtained a surgical internship and subsequently, despite a poor evaluation, a neurosurgery residency at The Ohio State University College of Medicine (from which he was ultimately terminated for slovenly work). His nickname was “Double-O Swango.” Nursing staff expressed their concerns, but administration thought they were being “paranoid.” He was licensed as a physician in the state of Ohio in 1984. This is where it gets interesting. In 1991, he legally changed his name to Daniel Adams after having been sentenced to five years in prison for aggravated battery — he poisoned his coworkers while working as an EMT. He then forged his criminal record to reduce the charge and created a “Restoration of Civil Rights” letter allegedly from the Governor of Virginia. -

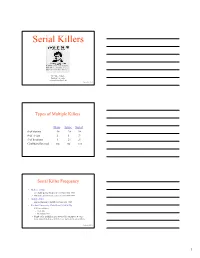

Serial Killers

Serial Killers Dr. Mike Aamodt Radford University [email protected] Updated 01/24/2010 Types of Multiple Killers Mass Spree Serial # of victims 4+ 2+ 3+ # of events 1 1 3+ # of locations 1 2+ 3+ Cooling-off period no no yes Serial Killer Frequency • Hickey (2002) – 337 males and 62 females in U.S. from 1800-1995 – 158 males and 29 females in U.S. from 1975-1995 • Gorby (2000) – 300 international serial killers from 1800-1995 • Radford University Data Base (1/24/2010) – 1,961 serial killers • US: 1,140 • International: 821 – Number of serial killers goes down with each update because many names listed as serial killers are not actually serial killers Updated 01/24/2010 1 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics - Worldwide • Male – Our data base: 88.27% – Kraemer, Lord & Heilbrun (2004) study of 157 serial killers: 96% • White – 66.5% of all serial killers (68% in Kraemer et al, 2004) – 64.3% of male serial killers – 83% of female serial killers • Average intelligence – Mean of 101 in our data base (median = 100) –n = 107 • Seldom involved with groups Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Age at First Kill Race N Mean Our data (2010) 1,518 29.0 Kraemer et al. (2004) 157 31 Hickey (2002) 28.5 Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics – Average age is 29.0 • Males – 28.8 is average age at first kill • 9 is the youngest (Robert Dale Segee) • 72 is the oldest (Ray Copeland) – Jesse Pomeroy (Boston in the 1870s) • Killed 2 people and tortured 8 by the age of 14 • Spent 58 years in solitary confinement until he died • Females – 30.3 is average age at first kill • 11 is youngest (Mary Flora Bell) • 66 is oldest (Faye Copeland) Updated 01/24/2010 2 General Serial Killer Profile Race Race U.S. -

Quincy{Off the Record} the Famous & Infamous 13

Quincy{Off the Record} the famous & infamous 13 bizarre brow-raising spooky spine-tingling astounding & amazing self-guided driving tour of places associated with some of the Quincy area’s intriguing former residents SEEO seequincy.com~ KEY to People and Locations to see MARY ASTOR 1 2435 N 12th Hollywood film star in The Maltese Falcon JENNIE HODGERS / ALBERT CASHIER 2 1707 N 12th Cashier’s secret identity as a woman MONCKTON MANSION 3 1419 Locust Mob activity & Queen Victoria-commisioned chandelier JOHN MAHONEY 4 1627 College Frasier star, the beloved Marty Crane JAMES B STEWART / MICHAEL SWANGO 5/6 220 N 18th Prize-winning author / “Dr. Death” serial killer JAMES EARL RAY 7 415 Hampshire Convicted assassin of Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. JOHN ANDERSON 8 510 Maine Brilliant character actor in over 500 T.V. roles DICK BROTHERS BREWERY 9 9th & York “Sudsy” the ghost & underground tunnels ROY BROCKSMITH 10 1020 S 5th From bar singing at age 3 to Arachnophobia WOODLAND CEMETERY / JOHN WOOD 11 1020 S 5th 60,000 rest here, including Wood’s father’s “head” JONATHAN BROWNING 12 350 N Main World famous firearms inventor & polygamist Nauvoo ROBERT EARL HUGHES 13 400 E Jefferson World’s heaviest man at 1,041 pounds Pittsfield kochs ln us hwy 24 1 il veterans home 2 3 locust st quincy front st front univ college ave 4 mississippi river 8th st 6th st 4th st 5th st 3rd st 12th st 18th st broadway st us 24 to MO v vermont st 7 hampshire st 5/6 v washington park maine st 8 york st east end 9 historic district state st VISITOR CENTER/villa kathrine Hgardner expy 10/11 jefferson st 12 woodland cemetery NAUVOO 57 harrison st 96 south park QUINCY I-72 PITTSFLD 13 Mary Astor 1 1906-1987 An only child, Mary Astor was born Lucile Langhanke on May 3, 1906 in Quincy, to German immigrant father, Otto Langhanke, and mother from Illinois, Helen Vasconcellos. -

Credentialing: Details, Details, Details

3/3/2020 Credentialing: Details, Details, Details Ann Geier, MS, RN, CNOR(E), CASC® Chief Nursing Officer Surgical Information Systems (SIS) 2 1 3/3/2020 Objectives At the conclusion of this program, the attendee will: 1. Understand the differences between Credentialing, Privileging, and Peer Review 2. Develop steps in the credentialing process that will safeguard the ASC 3. Establish guidelines to ensure that physicians are safe to practice in your ASC 3 Why is Credentialing So Important? • From 2001 – 2011 nearly 6,000 doctors had clinical privileges restricted or taken away for misconduct • But 52% — more than 3,000 doctors — were never fined or hit with a license restriction, suspension or revocation by a state medical board.¹ • In 2012, 6949 adverse action reports were submitted to NPDB² • Impersonators 2 NPDB 2012 Annual Report, 55 4 2 3/3/2020 Do You Know Who This Is? 5 Michael Swango, MD 6 3 3/3/2020 Michael Swango, MD • In 2000, pleaded guilty to murdering 3 patients by poisoning them while a hospital physician. He is suspected of administering lethal injections to 35 – 60 patients • If hospital had done its job, it would have learned: » Medical school wrote warning letter » Numerous deaths occurred during his rounds » Convicted & imprisoned for 2 years for poisoning coworkers » Pled guilty to fraud in applications to government hospitals » Ohio revoked his medical license » Dismissed from programs and rejected by hospitals » Featured on 20/20 and America’s Most Wanted Blind Eye: How the Medical Establishment Let a Doctor Get -

The BG News May 1, 1985

Bowling Green State University ScholarWorks@BGSU BG News (Student Newspaper) University Publications 5-1-1985 The BG News May 1, 1985 Bowling Green State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news Recommended Citation Bowling Green State University, "The BG News May 1, 1985" (1985). BG News (Student Newspaper). 4394. https://scholarworks.bgsu.edu/bg-news/4394 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-No Derivative Works 4.0 License. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the University Publications at ScholarWorks@BGSU. It has been accepted for inclusion in BG News (Student Newspaper) by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@BGSU. Wednesday, May 1,1985THE J3CL NEWS Vol. 67 Issue 119 College of Technology created by Michael Mclntyre Technology Systems and Department of 1983," Lunde said. "The increase in give a test, major quiz, or assign a Debate continued, and the Senate staff reporter of VisuaTComniunications and Tech- costs won't occur because it already major project during the week prior to finally decided to vote within itself nology Education. has." final exam week. whether or not to change the word. Faculty Senate voted yesterday to Most of the debate centered around He said the name change would add The resolution was changed to in- They voted in favor oi the change and change the name of the School of Tech- the budgetary implications of creating to the prestige of the technology pro- clude that laboratory tests and the immediately passed the resolution. nology to the College of Technology, a new college. -

Lessons from the Worst-Case Scenario, Mar 04 ... AMA Journal Of

Virtual Mentor. March 2004, Volume 6, Number 3. doi: 10.1001/virtualmentor.2004.6.3.oped2-0403 Op-Ed Lessons from the Worst-Case Scenario A system of physician self-regulation will help ensure patient safety and quality medical care. Erin Egan, MD, JD Michael Swango was a physician—and—a serial killer [1]. Swango killed hospitalized patients, those under his care or others just in the wrong place at the wrong time. To say that a serial killer is too personally culpable and too extreme to provide meaningful lessons on patient safety ignores the critical patient safety and system issues that we need to acknowledge and address to prevent harm to patients. Clinical case 2 in this issue, "Problem Peers," brings up the common scenario in which a physician represents a safety concern that peers are aware of. This scenario occurs everywhere, at every level of medical education. The Swango case illustrates how, even when the worst happens, the system is not effective at dealing with problem physicians. Michael Swango was a problem student and a problem resident. His medical school classmates feared for the safety of Swango's patients, calling him "double-O Swango," meaning he had a "license to kill" [2]. The high mortality among Swango's patients was noted by the students and residents he worked with as soon as he began clinical training [3]. He was dismissed from a residency position after the hospital suspected him of poisoning a patient—not through poor medical care but by injecting something into the IV of a patient who was not under his care [4]. -

OSBN Sentinel, November 2020

OREGON BOARD OF NURSING [ VO.39V ▬ NO.4 ▬ NOVEMBER 2020 ] Also in this issue Freedom Of Speech, Hate Speech, And The Nurse Practice Act AA REGULATORYREGULATORY RESPONSERESPONSE TOTO HEALTHCAREHEALTHCARE SERIALSERIAL KILLINGKILLING Advanced training for YOUR advance nursing caree All of ASU’s MS in Nursing graduates Take the next step in your nursing career and earn your MS in Nursing! The 100% online are prepared to address MS in Nursing program from Arizona three main objectives: State University develops the in-depth skills you need to excel in a wide variety Deliver comprehensive of nursing and health care settings. nursing care in partnership When you enroll with ASU, you expand your with individuals, families, nursing skills with a deeper understanding groups and communities, of evidence-based practice, leadership, 1 pathophysiology and how to meet workforce and populations. demands. This graduate program is ideal for anyone looking to upgrade their nursing career while building on their own education. Develop theoretical and practice-based nursing education across diverse 2 care settings. Demonstrate knowledge and skills needed to analyze, use and generate evidence for 3 application to practice. Edson College of Learn more at Nursing and Health Innovation nursingandhealth.asu.edu/msnonline TABLE OF CONTENTS Oregon State Board of Nursing 17938 SW Upper Boones Ferry Road Portland, OR 97224-7012 SENTINEL Phone: 971-673-0685 ▬ ▬ Fax: 971-673-0684 [VO.39 NO.4 NOVEMBER 2020] www.oregon.gov/OSBN contentstable of ÑġßáÊëñîï Monday - Friday 8:00 a.m. - 4:30 p.m. ÒäëêáÊëñîï A Regulatory Response To Healthcare ÒäëêáÊëñîïîáàñßáàâëîðäáàñîÝðåëê Serial Killing ........................4 ëâðäáÉëòáîêëîĊïÇôáßñðåòáÑîàáîëê Covid-19. -

Armando D. Meza MD Associate Professor of Medicine Associate

Armando D. Meza MD Associate Professor of Medicine Associate Dean GME TTUHSC-PLFSOM El Paso Program Directors Training Course Selected Topics PDTC-9 Disciplinary Policy Resident Evaluation: A Focus on Failing to Fail Michael Swango • Born: 1954, Tacoma, • Decision is made to delay his Washington. graduation date by one year. • Valedictorian in HS. • His dropped from his prior matched program but • He enrolled in Southern reapplies. Illinois University School of • In 1983 he starts a NS residency Medicine. at Ohio State. -- Performance uneventful • Unexpected patients’ deaths until his last year of school. are associated with him and his – 1983, matches for contract is not renewed. neurosurgery. • In 1984 he is rehired as an EMT. – He fails his last rotation due • In 1985 he is convicted of to plagiarism or fabrication. aggravated battery. – Case referred to the Student Progress Committee. Michael Swango • 1991 he changes his name to • 1994 his is working as a chemist Daniel J. Adams. in Atlanta. • In 1992 he is hired as a • 1994 he moves to Zimbabwe physician Sanford USD Medical and starts practicing medicine. Center in Sioux Falls with • He then crosses to Zambia and falsified application then Namibia. information. • 1997 he is arrested at Chicago- • Swango is fired a few months O’Hare on his way to Saudi later. Arabia. • Swango manages to start a • He eventually pleads guilty and Psychiatric residency at Stony is sentenced to 3 consecutive Brook but is fired when his past life terms. is discovered. Residents in Trouble • Typical scenario: • Reality: – Surprise – A pattern – Oddity – Overlooked – A fluke – Never addressed – An accident – Never remediated – A rare event – Allowed to continue – Give them another opportunity Potential Explanations • Faculty not competent • Do not want to “ruin” to identify these their career. -

U.S. Dept. of Veterans Affairs Office of Inspector General Semiannual

Office of Inspector General Semiannual Report to Congress April 1, 2000 – September 30, 2000 FOREWORD I am pleased to submit the semiannual report on the activities of the Department of Veterans Affairs (VA), Office of Inspector General (OIG) for the period ended September 30, 2000. The OIG is dedicated to help ensure that veterans and their families receive the care, support, and recognition they have earned through service to their country. This report is issued in accordance with the provisions of the Inspector General Act of 1978, as amended. Most significant in the protection of veterans was the prosecution of Dr. Michael Swango. After a 7-year investigation by our Office of Investigations, with assistance by our Office of Healthcare Inspections, Swango pleaded guilty in Federal court to the murder of three veterans under his care at a VA medical center (VAMC). He also admitted to the murder of a 19-year-old patient at a university hospital in 1984. Swango was sentenced to three consecutive life terms in prison with no possibility of parole. Our criminal investigations continue to target cases of public corruption and major thefts, instances where incapacitated veterans fall victim to unscrupulous individuals, and fraud involving programs for the delivery of benefits to veterans. We place a priority on safety and security at VA medical centers. Allegations of fraud demand an immediate response. The OIG will take decisive action against those who prey on veterans and will hold accountable those VA employees who disregard their public trust responsibilities. During the period, OIG criminal and administrative investigations yielded 174 arrests, 156 indictments, 122 criminal convictions, and 195 administrative actions, foremost of which were cases involving fraud and employee misconduct. -

Volume 3 – a Strategy for Safety

Public Inquiry into the Safety and Security of Residents in the Long-Term Care Homes System REPORT The Honourable Eileen E. Gillese Commissioner Volume 1 – Executive Summary and Consolidated Recommendations Volume 2 – A Systemic Inquiry into the Offences Volume 3 – A Strategy for Safety Volume 4 – The Inquiry Process Public Inquiry into the Safety and Security of Residents in the Long-Term Care Homes System REPORT The Honourable Eileen E. Gillese Commissioner Volume 1 – Executive Summary and Consolidated Recommendations Volume 2 – A Systemic Inquiry into the Offences Volume 3 – A Strategy for Safety Volume 4 – The Inquiry Process This Report consists of four volumes: 1. Executive Summary and Consolidated Recommendations 2. A Systemic Inquiry into the Offences 3. A Strategy for Safety 4. The Inquiry Process ISBN 978-1-4868-3586-7 (PDF) ISBN 978-1-4868-3582-9 (Print) © Queen’s Printer for Ontario, 2019 Disponible en français VOLUME 3 Contents VOLUME 1: Executive Summary and Consolidated Recommendations VOLUME 2: A Systemic Inquiry into the Offences VOLUME 3: A Strategy for Safety Dedication ......................................................... iv Acronyms and Abbreviations .................................... .v Chapter 15: Building Capacity and Excellence in the Long‑Term Care System ...................................... 1 Chapter 16: Building Awareness of the Healthcare Serial Killer Phenomenon ................................... .25 Chapter 17: Deterrence Through Improved Medication Management .................................... 71 Chapter 18: Detecting Intentionally Caused Resident Deaths ............................................. 133 Chapter 19: Suggestions Not Pursued ......................... 173 Appendices ...................................................... 183 Appendix G – A Just Culture Guide ............................... 184 VOLUME 4: The Inquiry Process Dedication Volume 3 of the Report is dedicated to the many nurses and other caregivers who perform their jobs in the long-term care system with great kindness and skill. -

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE

Criminal Poisoning FORENSIC SCIENCE- AND- MEDICINE Steven B. Karch, MD, SERIES EDITOR CRIMINAL POISONING: INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS, SECOND EDITION, by John H. Trestrail, III, 2007 MARIJUANA AND THE CANNABINOIDS, edited by Mahmoud A. ElSohly, 2007 FORENSIC PATHOLOGY OF TRAUMA: COMMON PROBLEMS FOR THE PATHOLOGIST, edited by Michael J. Shkrum and David A. Ramsay, 2007 THE FORENSIC LABORATORY HANDBOOK: PROCEDURES AND PRACTICE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Carla Noziglia, 2006 SUDDEN DEATHS IN CUSTODY, edited by Darrell L. Ross and Ted Chan, 2006 DRUGS OF ABUSE: BODY FLUID TESTING, edited by Raphael C. Wong and Harley Y. Tse, 2005 A PHYSICIAN’S GUIDE TO CLINICAL FORENSIC MEDICINE: SECOND EDITION, edited by Margaret M. Stark, 2005 FORENSIC MEDICINE OF THE LOWER EXTREMITY: HUMAN IDENTIFICATION AND TRAUMA ANALYSIS OF THE THIGH, LEG, AND FOOT, by Jeremy Rich, Dorothy E. Dean, and Robert H. Powers, 2005 FORENSIC AND CLINICAL APPLICATIONS OF SOLID PHASE EXTRACTION, by Michael J. Telepchak, Thomas F. August, and Glynn Chaney, 2004 HANDBOOK OF DRUG INTERACTIONS: A CLINICAL AND FORENSIC GUIDE, edited by Ashraf Mozayani and Lionel P. Raymon, 2004 DIETARY SUPPLEMENTS: TOXICOLOGY AND CLINICAL PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Melanie Johns Cupp and Timothy S. Tracy, 2003 BUPRENOPHINE THERAPY OF OPIATE ADDICTION, edited by Pascal Kintz and Pierre Marquet, 2002 BENZODIAZEPINES AND GHB: DETECTION AND PHARMACOLOGY, edited by Salvatore J. Salamone, 2002 ON-SITE DRUG TESTING, edited by Amanda J. Jenkins and Bruce A. Goldberger, 2001 BRAIN IMAGING IN SUBSTANCE ABUSE: RESEARCH, CLINICAL, AND FORENSIC APPLICATIONS, edited by Marc J. Kaufman, 2001 CRIMINAL POISONING INVESTIGATIONAL GUIDE FOR LAW ENFORCEMENT, TOXICOLOGISTS, FORENSIC SCIENTISTS, AND ATTORNEYS Second Edition John Harris Trestrail, III, RPh, FAACT, DABAT Center for the Study of Criminal Poisoning, Grand Rapids, MI © 2007 Humana Press Inc. -

Identification of Psychosocial Factors in the Development of Serial Killers in the Nitu Ed States Tiffany Brennan

Salem State University Digital Commons at Salem State University Honors Theses Student Scholarship 2019-05-01 Identification Of Psychosocial Factors In The Development Of Serial Killers In The nitU ed States Tiffany Brennan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/honors_theses Part of the Psychiatry and Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Brennan, Tiffany, "Identification Of Psychosocial Factors In The eD velopment Of Serial Killers In The nitU ed States" (2019). Honors Theses. 216. https://digitalcommons.salemstate.edu/honors_theses/216 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at Digital Commons at Salem State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons at Salem State University. i IDENTIFICATION OF PSYCHOSOCIAL FACTORS IN THE DEVELOPMENT OF SERIAL KILLERS IN THE UNITED STATES Honors Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Bachelor of Science in Psychology In the School of Psychology at Salem State University By Tiffany Brennan Dr. Joanna Gonsalves Faculty Advisor Department of Psychology *** Commonwealth Honors Program Salem State University 2019 1 Abstract The purpose of this study is to attempt to identify risk factors associated with serial killing. This line of investigation can aid criminal justice and mental health professionals in preventing murders in the future. Twenty-five case studies of serial killers convicted in the United States between 1967 and 2016 were examined using newspapers, books, biographies, and social science peer reviewed articles. The analyses focused on demographic, psychological, and sociological factors, such as mental illness and criminality, that may have predisposed the sample to become serial killers.