Caring to Death: a Discursive Analysis of Nurses Who Murder Patients

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

ICRC Duty of Care: Elements of Definition

ICRC Duty of Care: elements of definition Definition “Duty of care” (DoC) is a legal concept that comes from common law and can be defined as a legal obligation requiring adherence to a standard of reasonable care while performing any acts that could foreseeably harm others. Another definition of DoC would be a legal obligation to act towards others with prudence and vigilance in order to prevent any risk of foreseeable damage. The (legal) consequence of a breach of such a duty is a legal liability imposed upon the author (of the breach) to compensate the victim for any losses they incur. DoC entails an obligation of means (obligation de moyens) as opposed to an obligation of result (obligation de résultat). This means that the author must take all appropriate measures and behave in an appropriate way in order to avoid causing harm to third parties. This being said, the fact that harm is done does not necessarily mean that the duty of care was breached (or, in other words that the author was negligent), as certain events are beyond the control of the author (because they were unforeseeable or unavoidable despite proper care being taken). The ICRC’s DoC obligations towards the defined population hence depend on the nature of the relationship between the ICRC and the concerned population (employees, accompanying dependents, Movement partners, external contractual partners) and the relevant (legal and contractual) provisions applicable to such relationship. Content The actual measure, scope or content of the “care” that is required in each situation depends primarily on two factors: (i) the relationship between the parties and (ii) the applicable law. -

The Guardian World News Guide Arts Special Reports Columnists Audio Help Quiz

Guardian Unlimited | Guardian daily comment | Tim Lott: The ultimate act of will Page 1 of 4 Sign in Register Go Go to: Guardian Unlimited home Home UK Business Online World dispatch The Wrap Weblog Talk Search The Guardian World News guide Arts Special reports Columnists Audio Help Quiz Comment The ultimate act of will Suicide is often the choice of physical death over psychological annihilation Tim Lott Search this site Saturday January 17, 2004 The Guardian Go The delight of some sections of the press and public at the suicide of Harold Shipman this week was shocking and depressing to me. I felt that way, not because I am high- minded enough to extract "tragedy" from Shipman's demise, but because to express such naked merriment at the suicide of any human being, evil or good, seems a small triumph for the part of us all that hates life. I wouldn't go as far as John Donne in claiming that "any man's death diminishes me because I am involved in mankind". Yet to clap and dance at the spectacle of somebody, however wretched, extinguishing themselves, verges on the savage - and that is what diminishes us. I don't feel that Shipman's death itself diminished me, any more than Fred West's. But I couldn't celebrate. I felt a grim satisfaction and a vague regret for the destructiveness, and wastefulness, of his life. But one's reaction to suicide is highly personal and, in many cases, profoundly political. The public tend to classify self-murder into what you might call In this section "good" and "sad" suicides. -

Strange, and Ultimately Dangerous, Credentialing Scenarios Highlight the Need for Msps’ Roles to Protect the Public

Strange, and ultimately dangerous, credentialing scenarios highlight the need for MSPs’ roles to protect the public April 3, 2018 For those of you who were unable to join us at NAMSS this year, we thought you might enjoy a recap of our session regarding strange credentialing scenarios. It is true that fact can be stranger than fiction, but these situations make it very clear that the role of the MSP is critical in today’s fast-paced world. The Danger of Not Doing Your Homework We begin with a history lesson — Michael Swango. He was valedictorian of his class and awarded a National Merit scholarship. His favorite movie was “Silence of the Lambs,” and he kept a scrapbook of car wrecks. He graduated from medical school in 1983, and during that time, five of the patients he cared for died. He obtained a surgical internship and subsequently, despite a poor evaluation, a neurosurgery residency at The Ohio State University College of Medicine (from which he was ultimately terminated for slovenly work). His nickname was “Double-O Swango.” Nursing staff expressed their concerns, but administration thought they were being “paranoid.” He was licensed as a physician in the state of Ohio in 1984. This is where it gets interesting. In 1991, he legally changed his name to Daniel Adams after having been sentenced to five years in prison for aggravated battery — he poisoned his coworkers while working as an EMT. He then forged his criminal record to reduce the charge and created a “Restoration of Civil Rights” letter allegedly from the Governor of Virginia. -

Subtle Misperceptions Has Real Consequences and Those Con- from Cullen Himself

Reviews of Educational Material subtle misperceptions has real consequences and those con- from Cullen himself. After coworkers and hospital officials sequences can be directly attributed to misunderstood biases became suspicious because of a pattern of inappropriate and the analyses based on those biases. We recommend that deaths on Cullen’s shifts, they conducted their own inter- every clinician, researcher, and administrator takes the time nal, superficial, and ineffective investigations, each of which to read this book and consider his or her own biases. led to Cullen being asked to resign, with the proviso that he would be issued a neutral letter of reference, and some- Amy M. Shanks, M.S, Sachin Kheterpal, M.D., M.B.A.* times resulted in disciplinary action for the whistle blower. *University of Michigan Medical School, Ann Arbor, Michi- Although some hospitals strongly suspected Cullen of poi- gan. [email protected] soning patients, they chose not to alert authorities because of the negative publicity that would be generated. (Accepted for publication May 30, 2013.) The case gained strength when a pharmacist at Somerset Downloaded from http://pubs.asahq.org/anesthesiology/article-pdf/119/6/1496/264176/20131200_0-00042.pdf by guest on 30 September 2021 Hospital in New Jersey called the State’s Department of Poi- son Control to inquire about the dose of digoxin required to achieve the astronomically high levels found in the bodies of The Good Nurse: A True Story of Medicine, two victims after their deaths. Neither patient was ordered Madness, and Murder. By Charles Graeber. New to receive digoxin nor was there any record of its administra- York, Twelve–Hachette Book Group, 2013. -

Free Land Attracted Many Colonists to Texas in 1840S 3-29-92 “No Quitting Sense” We Claim Is Typically Texas

“Between the Creeks” Gwen Pettit This is a compilation of weekly newspaper columns on local history written by Gwen Pettit during 1986-1992 for the Allen Leader and the Allen American in Allen, Texas. Most of these articles were initially written and published, then run again later with changes and additions made. I compiled these articles from the Allen American on microfilm at the Allen Public Library and from the Allen Leader newspapers provided by Mike Williams. Then, I typed them into the computer and indexed them in 2006-07. Lois Curtis and then Rick Mann, Managing Editor of the Allen American gave permission for them to be reprinted on April 30, 2007, [email protected]. Please, contact me to obtain a free copy on a CD. I have given a copy of this to the Allen Public Library, the Harrington Library in Plano, the McKinney Library, the Allen Independent School District and the Lovejoy School District. Tom Keener of the Allen Heritage Guild has better copies of all these photographs and is currently working on an Allen history book. Keener offices at the Allen Public Library. Gwen was a longtime Allen resident with an avid interest in this area’s history. Some of her sources were: Pioneering in North Texas by Capt. Roy and Helen Hall, The History of Collin County by Stambaugh & Stambaugh, The Brown Papers by George Pearis Brown, The Peters Colony of Texas by Seymour V. Conner, Collin County census & tax records and verbal history from local long-time residents of the county. She does not document all of her sources. -

A CALL for FEDERAL IMMUNITY to Protect Health Care Employers…And Patients Page 2 APRIL 2005

A call for federal immunity to protect health care employers … and patients Published April 2005 © 2005 American Society for Healthcare Risk Management of the American Hospital Association ONE NORTH FRANKLIN, CHICAGO, IL 60606 (312) 422-3980 W WW.ASHRM. ORGXGG TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................................... 3 History of the issue ..................................................................................................................... 3 Facing the fear of litigation ...................................................................................................... 4 CURRENT STATE OF THE LAW ................................................................................................................ 4 Federal law provides some immunity................................................................... ...... 4 State laws face issue to varying degrees ............................................................... ...... 5 CONCLUSION .............................................................................................................................................. 8 RESOURCES ................................................................................................................................................ 9 REPRINTING THIS MONOGRAPH ..........................................................................................................9 A CALL FOR FEDERAL IMMUNITY to protect health -

2009/2010 Insurance Handbook Australian Underwater Federation

‘Private and Confidential’ 2009/2010 Insurance Handbook Australian Underwater Federation Inc. for the period 1st July 2009 to 1 st July 2010 Prepared by: OAMPS Insurance Brokers Ltd Level 2, 8 Gardner Close, Milton, QLD 4064 GPO Box 1113, Brisbane, QLD 4001 Phone: (07) 3367 5000 Fax: (07) 3367 5100 OAMPS Insurance Brokers Ltd ABN 34 005 543 920 Level 2, 8 Gardner Close, Milton QLD 4064 GPO Box 1113 Brisbane QLD 4001 T (07) 3367 5160 F (07) 3367 5100 E [email protected] W www.oamps.com.au Members & Affiliates Australian Underwater Federation Inc. and Affiliated Bodies We have pleasure in enclosing details of the AUF National Insurance Program for the 2009/2010 policy period. It is essential that each Club Executive advise all Members, Officials and Volunteers associated with them of this minimum level of Insurance cover. It must be clearly understood that after being informed of the level of cover taken out, it is an individual’s responsibility to ensure that he/she has adequate Insurance cover for his/her needs. In addition to these policies all players and officials may, and are encouraged to take out private health and income protection insurance. The 2009/2010 program benefits are outlined in detail in this Handbook. OAMPS Insurance Brokers services include professional advice on the complete range of general insurance products, we welcome the opportunity to assist you with all your insurance needs. Kind Regards Mathew Lethborg Senior Portfolio Manager OAMPS Insurance Brokers Ltd ABN 34 005 543 920 Level 2, 8 Gardner Close, Milton, Qld., 4064 Phone: (07) 3367 5145 Fax: (07) 3367 5100 Mobile: 0409 852 838 Email: [email protected] Web: www.oamps.com.au Page 1 Summary of Covers Cover under the Program consists of the following: 1. -

'Last Seen Before Death': the Unrecognised Clue in the Shipman

Qualityin Primary Care 2004;12:5- 11 # 2004 Radcli¡ eMedicalPress Researchpapers ©Last seenbeforedeath ©:theunrecognised clueintheShipmancase GuyHoughton MAMB FR CGP GPAdvisor,BirminghamPublicH ealthH ub,and SeniorPar tner,Gree nbank Surgery,HallGreen, Birmingham,UK ABSTRACT Therehave beenvery few mortality surveys at 8% ofpatients wereseen alive on the day ofdeath, in individual practice level.This lackof robust com- comparison with Dr Shipman actuallyin attend- parative informationis oneof the reasons why the anceat almost 20% ofhis patients’deaths. fullextent of HaroldShipman’ s possible murderous Althoughthese areonly the results ofa single activities wentunrecognised until Richard Baker practice study, theyo ¡era benchmarkfor further undertookhis comprehensive study as apart ofthe comparative data collectionto dene patterns of o¤cialShipman Inquiry. mortality inthe community.They also suggest only This review looksat 752 deaths over11 years ina minormodi cations to the notication of cause of singlesuburban Birmingham practice. Inaddition death procedures areneeded to identifyanother to recordingthe age and sex ofthe patient, and the Shipman. placeand cause ofdeath, the extra, previously unrecorded,parameter ofwhen the generalpracti- Keywords:cause ofdeath, last seenbefore death, tionerlast saw the patient alivewas included.Only placeof death Introduction formfor the notication of cause ofdeath asks when the certifyingpractitioner last saw the patient before death, there have beenno studies lookingat the The discovery ofthe fullextent -

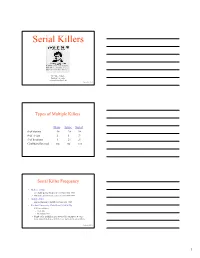

Serial Killers

Serial Killers Dr. Mike Aamodt Radford University [email protected] Updated 01/24/2010 Types of Multiple Killers Mass Spree Serial # of victims 4+ 2+ 3+ # of events 1 1 3+ # of locations 1 2+ 3+ Cooling-off period no no yes Serial Killer Frequency • Hickey (2002) – 337 males and 62 females in U.S. from 1800-1995 – 158 males and 29 females in U.S. from 1975-1995 • Gorby (2000) – 300 international serial killers from 1800-1995 • Radford University Data Base (1/24/2010) – 1,961 serial killers • US: 1,140 • International: 821 – Number of serial killers goes down with each update because many names listed as serial killers are not actually serial killers Updated 01/24/2010 1 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics - Worldwide • Male – Our data base: 88.27% – Kraemer, Lord & Heilbrun (2004) study of 157 serial killers: 96% • White – 66.5% of all serial killers (68% in Kraemer et al, 2004) – 64.3% of male serial killers – 83% of female serial killers • Average intelligence – Mean of 101 in our data base (median = 100) –n = 107 • Seldom involved with groups Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Age at First Kill Race N Mean Our data (2010) 1,518 29.0 Kraemer et al. (2004) 157 31 Hickey (2002) 28.5 Updated 01/24/2010 General Serial Killer Profile Demographics – Average age is 29.0 • Males – 28.8 is average age at first kill • 9 is the youngest (Robert Dale Segee) • 72 is the oldest (Ray Copeland) – Jesse Pomeroy (Boston in the 1870s) • Killed 2 people and tortured 8 by the age of 14 • Spent 58 years in solitary confinement until he died • Females – 30.3 is average age at first kill • 11 is youngest (Mary Flora Bell) • 66 is oldest (Faye Copeland) Updated 01/24/2010 2 General Serial Killer Profile Race Race U.S. -

NURSING for the 21St Century

Adapting NURSING for the 21st century Alumni Association & Development Foundation • Spring 2021 4 - 14 -21 2 CONNECTIONS Spring ’21 CONNECTIONS STAFF Vice President for Advancement Rick Hedberg ’89 Managing Editor Michael Linnell Greetings from the MSU Writing Staff campus! Winter in Minot Michael Linnell Amanda Duchsherer ’06 has been mild for much Dan Fagan ’18 of this season, but it Emily Schmidt roared to life in early/mid Jeff Bowe February. As I type this Photographers afternoon, it is minus 10 Richard Heit ’08 with a wind chill of minus Janna McKechnie ’14 37. These are the days that Photography Coordinator always make me especially Teresa Loftesnes ’07/’15 appreciative of our other Publication Design three seasons in North Doreen Wald Dakota! Alumni Happenings We are nearing the Janna McKechnie ’14 midpoint of the spring Baby Beavers semester, and I want to Kate Marshall ’07 publicly applaud our Class Notes entire community of Bonnie Trueblood students, faculty, staff, In Memory and administration for the Renae Yale ’10 roles they have played in ensuring the campus has ADDITIONAL PHOTO CREDITS: remained open this entire academic year. We have had our peaks and valleys like any other university, ON THE COVER: Minot State University but as the light at the end of this pandemic tunnel slowly gets brighter, I am heartened by the resilience nursing professors Carrie Lewis, April Warren, and Melissa Fettig inside the new nursing simulation lab in Memorial Hall. The space tripled the amount of andof everyone teamwork who have has beenhelped incredibly lead MSU important to a safe and characteristics. -

Shred-It Is the Right Prescription For

“Shred-it“Shred-it isis thethe rightright prescriptionprescription forfor youryour HIPAAHIPAA headache.”headache.” Government legislation. Budget restrictions. Patient privacy. They don’t need to be a headache. Nationwide, companies like yours are turning to Shred-it for realistic solutions to their immediate security concerns, and HIPAA compliance mandates. Shred-it is the world’s largest on-site document destruction and recycling company. Servicing more U.S. healthcare organizations than any other company, Shred-it is the medical industry’s choice for secure, cost-effective shredding. Alleviate your HIPAA headache. Call for a FREE Estimate. 1 800 69-SHRED • www.shredit.com PEOPLE Recognition Rosemarie Bigsby at W&I honored for contributions to neonatal care Betty Vohr, MD, receives PROVIDENCE – ROSEMARIE BIGSBY, award for contributions to ScD, OTR/L, FAOTA, has been elected as a recipient of the National Associa- high-risk infant care tion of Neonatal Therapists (NANT) PROVIDENCE – BETTY VOHR, MD, for the inaugural Pioneer Award for medical director of the Neonatal Fol- Neonatal Therapy. low-Up Program in the Department of She is a clinical professor of pediatrics, Pediatrics at Women & Infants Hos- psychiatry and human behavior at the pital and professor of pediatrics at the Alpert Medical School and coordinator Alpert Medical School, was awarded of neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) WOMEN & INFANTS the Stan and Mavis Graven’s Leader- services at the Brown Center for the Study of Children at Risk/ ship Award for Outstanding Contribu- Center for Children and Families of Women & Infants Hospital. tions to Enhancing the Physical and Bigsby was honored with the award at the 5th Annual NANT WOMEN & INFANTS Developmental Environment for High- Conference recently in Phoenix, AZ. -

Media Request

(b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c ICE.000001.09-830 (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c ICE.000002.09-830 (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c ICE.000003.09-830 (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c ICE.000004.09-830 (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c ICE.000005.09-830 (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6), (b)(7)c (b)(6) (b)(6) (b)(6) (b)(6) (b)(6) ICE.000006.09-830 jobs elseNhe.::-e.