Gandhi the Man

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter I Introduction

CHAPTER I INTRODUCTION Nonviolence is the pillar of Gandhi‘s life and work. His concept of nonviolence was based on cultivating a particular philosophical outlook and was integrally associated with truth. For him, nonviolence not just meant refraining from physical violence interpersonally and nationally but refraining from the inner violence of the heart as well. It meant the practice of active love towards one‘s oppressor and enemies in the pursuit of justice, truth and peace; ―Nonviolence cannot be preached‖ he insisted, ―It has to be practiced.‖ (Dear John, 2004). Non Violence is mightier than violence. Gandhi had studied very well the basic nature of man. To him, "Man as animal is violent, but in spirit he is non-violent.‖ The moment he awakes to the spirit within, he cannot remain violent". Thus, violence is artificial to him whereas non-violence has always an edge over violence. (Gandhi, M.K., 1935). Mahatma Gandhi‘s nonviolent struggle which helped in attaining independence is the biggest example. Ahimsa (nonviolence) has been part of Indian religious tradition for centuries. According to Mahatma Gandhi the concept of nonviolence has two dimensions i.e. nonviolence in action and nonviolence in thought. It is not a negative virtue rather it is positive state of love. The underlying principle of non- violence is "hate the sin, but not the sinner." Gandhi believes that man is a part of God, and the same divine spark resides in all men. Since the same spirit resides in all men, the possibility of reforming the meanest of men cannot be ruled out. -

Kasturba Gandhi an Embodiment of Empowerment

Kasturba Gandhi An Embodiment of Empowerment Siby K. Joseph Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai 2 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. All rights reserved. No part of this work may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publishers. The views and opinions expressed in this book are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of the organizations to which they belong. First Published February 2020 Reprint March 2020 © Author Published by Gandhi Smarak Nidhi, Mumbai Mani Bhavan, 1st Floor, 19 Laburnum Road, Gamdevi, Mumbai 400 007, MS, India. Website :https://www.gsnmumbai.org Printed at Om Laser Printers, 2324, Hudson Lines Kingsway Camp – 110 009 Siby K. Joseph 3 CONTENTS Foreword Raksha Mehta 5 Preface Siby K. Joseph 7-12 1. Early Life 13-15 2. Kastur- The Wife of Mohandas 16-24 3. In South Africa 25-29 4. Life in Beach Grove Villa 30-35 5. Reunion 36-41 6. Phoenix Settlement 42-52 7. Tolstoy Farm 53-57 8. Invalidation of Indian Marriage 58-64 9. Between Life and Death 65-72 10. Back in India 73-76 11. Champaran 77-80 12. Gandhi on Death’s door 81-85 13. Sarladevi 86-90 14. Aftermath of Non-Cooperation 91-94 15. Borsad Satyagraha and Gandhi’s Operation 95-98 16. Communal Harmony 99-101 4 Kasturba Gandhi: An Embodiment…. 17. Salt Satyagraha 102-105 18. Second Civil Disobedience Movement 106-108 19. Communal Award and Harijan Uplift 109-114 20. -

Bandha and Mudra

Mandala Yoga Ashram Yoga Teacher Training Course Prospectus September 2019 - July 2021 Mandala Yoga Ashram: Yoga Teacher Training Course 2019-2021 www.mandalayogaashram.co.uk 1 Introduction Mandala Yoga Ashram, under the guidance of Swami Nishchalananda, has been conducting authentic Yoga Teacher Training Courses (YTTC) for almost 30 years. The courses offer a unique training to all those who aspire to become quality yoga teachers from a strong foundation of personal practice, discovery and understanding. This 500-hour course will develop the skills and experience required to teach yoga to others as well as emphasising and promoting the deepening of each students’ personal yoga practice. The course is unique in the U.K. as it not only gives the essential skills and training to teach yoga to adults, but also a systematic training in how to teach both meditation and yoga nidra. Furthermore, students gain valuable exposure to Ashram life which gives an added depth and breadth of spiritual experience to enhance their teaching ability. The course will be for two years and includes a total of 69 days of tuition during residential retreats at the Ashram (see pg. 12). The course is well recognised within the U.K. and Ashram graduates successfully teach throughout the U.K. and abroad. Mandala Yoga Ashram: Yoga Teacher Training Course 2019-2021 www.mandalayogaashram.co.uk 2 Why choose this Course? • Authentic depth of training designed to encourage deeper realisation and awakening to our essential nature • A full training in teaching the popular -

Unit 1 Introducing Gandhi

UNIT 1 INTRODUCING GANDHI Structure 1.1 Introduction Aims and Objectives 1.2 Gandhi’s Methodology 1.3 Synthesis of the Material and the Spiritual 1.4 Nationalism and Internationalism 1.5 Summary 1.6 Terminal Questions Suggested Readings 1.1 INTRODUCTION “The greatest fact in the story of man on earth is not his material achievement, the empires he has built and broken but the growth of his soul from age to age in its search for truth and goodness. Those who take part in this adventure of the soul secure an enduring place in the history of human culture. Time has discredited heroes as easily as it has forgotten everyone else, but the saints remain. The greatness of Gandhi is more in his holy living than in his heroic struggles, in his insistence on the creative power of the soul and its life-giving quality at a time when the destructive forces seem to be in the ascendant.” - Dr. Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan How does one introduce Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi? As a frail man, striding across the globe like a colossus? As the indomitable champion of social justice and human rights? As a ‘half-naked’ saint seeking complete identification with the poor and the deprived, silently meditating at the spinning wheel, striving to find the path of salvation for the suffering humanity? It was Winston Churchill who contemptuously described Gandhi as a ‘half-naked fakir’ and an ‘old humbug’, adding that it was “alarming and nauseating to see Mr. Gandhi, a seditious Middle Temple lawyer, striding half-naked up the steps to the Vice-Regal Palace, to parley on equal terms with the representative of the King Emperor”. -

68-77 M.K. Gandhi Through Western Lenses

68 M.K.Gandhi through Western Lenses: Romain Rolland’s Mahatma Gandhi: The Man Who Became One With the Universal Being Madhavi Nikam Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume Department of English, Ramchand Kimatram Talreja College, Ulhasnagar [email protected] Sambhāṣaṇ 69 Abstract: Gandhi, an Orientalist could find a sublime place in the heart and history of the Westerners with the literary initiative of a French Nobel Laureate Romain Rolland. Rolland was a French writer, art historian and mystic who bagged Nobel Prize for Literature in 1915. Rolland’s pioneering biography (in the West) on Mohandas Karamchand Gandhi published in 1924, not only made him popular overnight but also restructured the Indian figure in the minds of people. Since the publication of his biography, number of biographies on Gandhi appeared in the market from various corners of the world. Rolland himself being a pacifist was impressed with Gandhi, a man with different life style and unique modus operandi. Pacifism has greatly benefited from the biographical and historiographical revival by contribution of such great authors. Gandhi’s firm belief in the democratic and four fundamental principles of Truth (Satya), non-violence (Ahimsa), welfare of all (Sarvodaya) and peaceful protest (Satyagraha) left an indelible impact on the writer which helped him to express his resentment at imperialism in his later works. The paper would attempt to reassess Gandhi as a philosopher, and revolutionary in the context with Romain Rolland’s correspondence with Gandhi written in 1923-24. The paper will be a sincere effort to explore Rolland ‘s first but lasting impression of Gandhi who offered attractive regenerative possibilities for Volume 1 : Issue 06, October 2020 Volume Europe after the great war. -

Encyclopedia of Hinduism | Vedas | Shiva

Encyclopedia of Hinduism J: AF Encyclopedia of Buddhism Encyclopedia of Catholicism Encyclopedia of Hinduism Encyclopedia of Islam Encyclopedia of Judaism Encyclopedia of Protestantism Encyclopedia of World Religions nnnnnnnnnnn Encyclopedia of Hinduism J: AF Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan J. Gordon Melton, Series Editor Encyclopedia of Hinduism Copyright © 2007 by Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording, or by any information storage or retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the pub- lisher. For information contact: Facts On File, Inc. An imprint of Infobase Publishing 132 West 31st Street New York NY 10001 ISBN-10: 0-8160-5458-4 ISBN-13: 978-0-8160-5458-9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Jones, Constance A., 1961– Encyclopedia of Hinduism / Constance A. Jones and James D. Ryan. p. cm. — (Encyclopedia of world religions) Includes index. ISBN 978-0-8160-5458-9 1. Hinduism—Encyclopedias. I. Ryan, James D. II. Title. III. Series. BL1105.J56 2006 294.503—dc22 2006044419 Facts On File books are available at special discounts when purchased in bulk quantities for businesses, associations, institutions, or sales promotions. Please call our Special Sales Department in New York at (212) 967-8800 or (800) 322-8755. You can find Facts On File on the World Wide Web at http://www.factsonfile.com Text design by Erika K. Arroyo Cover design by Cathy Rincon Printed in the United States of America VB Hermitage 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 This book is printed on acid-free paper. -

The Mountain Path Vol. 4 No. 3, July 1967

SRI RAMANASRAMAM, TIRUVANNAMALAI " Who can ever find Thee ? The Eye of the eye art Thou, and without eyes Thou seest, Oh Aruna- (A QUARTERLY) chala! " —The Marital Garland of " Arunachala! Thou dost root out the ego of those who Letters, verse 15.- meditate on Thee in the heart, Oh Arunachala ! " —The Marital Garland of Letters, verse 1. Publisher : Vol. IV JULY 1967 No. 3 T. N. Venkataraman, Sri Ramanasramam, Tiruvannamalai. CONTENTS Page EDITORIAL : Total Therapy . 181 Bhagavan on Yoga . 184 Editor : What Are We Waiting For?—Douglas Harding 185 Arthur Osborne, What Yoga is Not—Dr. Sampurnanand . 186 Sri Ramanasramam, Seeking (Poem)—L. P. Yandell . 188 Tiruvannamalai. Raja Yoga — The Royal Path —Prof. Eknath Easwaran . 189 Yama and Niyama—Prof. G. V. Kulkarni . 194 * Some Misconceptions about Yoga —Dr. I. K. Taimni . 197 Managing Editor : Yoga as Meditation—Prof. Eknath Easwaran . 201 V. Ganesan, The Meaning of Yoga in the Bhagavad Gita Sri Ramanasramam, —Prof. G. V. Kulkarni .. 204 Tiruvannamalai. In Quest of Yoga—Swami Sharadananda . 206 The Know-how of Yogic Breathing —Prof. K. S. Joshi . 208 Patanjali's Interception on Yoga —Dr. G. C. Pande . 213 Annual Subscription : Mouna Diksha—R. G. Kulkarni . 216 INDIA . Rs. 5. Some Aspects of Buddhist Yoga as Practised in FOREIGN . \0sh, $ 1.50. the Kargyudpa School of the Tibetan Vajrayana—Dorothy C. Donath .. 217 Life Subscription : Ignatian Yoga—/. Jesuuasan, S.J. , . 222 Rs. 100 ; <£ 10 ; $ 30. How I Came to the Maharshi—Dinker Rai . 224 Single Copy : Dialectic Approach to Integration—Wei Wu Wei 226 Rs. 1.50; 3 sh. ; $0.45 The New Apostles—Cornelia Bagarotti . -

Gandhi ´ Islam

tabah lectures & speeches series • Number 5 GANDHI ISLAM AND THE PRINCIPLES´ OF NON-VIOLENCE AND ATTACHMENT TO TRUTH by KARIM LAHHAM I GANDHI, ISLAM, AND THE PRINCIPLES OF NON-VIOLENCE AND ATTACHMENT TO TRUTH GANDHI ISLAM AND THE PRINCIPLES´ OF NON-VIOLENCE AND ATTACHMENT TO TRUTH by KARIM LAHHAM tabah lectures & speeches series | Number 5 | 2016 Gandhi, Islam, and the Principles of Non-violence and Attachment to Truth ISBN: 978-9948-18-039-5 © 2016 Karim Lahham Tabah Foundation P.O. Box 107442 Abu Dhabi, U.A.E. www.tabahfoundation.org All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or distributed in any manner without the express written consent of the author, except in the case of brief quotations with full and accurate citations in critical articles or reviews. This work was originally delivered as a lecture, in English, at the Cambridge Muslim College, Cambridge, England, on 11 March 2015 (20 Jumada I 1436). iN the Name of allah, most beNeficeNt, most merciful would like to speak a little tonight about what might at first be seen as incongruous I topics, Gandhi and Islam. It would be best therefore to set out the premises of my examination of Gandhi, given the diverse narratives that have been constructed since his assassination in 1948. Primarily, and as a main contention, I do not believe Gandhi to be essentially a political figure as we understand that term today. Furthermore, he never held a political post nor was he ever elected to one. This is not the same as saying that Gandhi did not engage in politics, which he naturally did. -

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648

NON-VIOLENCE NEWS February 2016 Issue 2.5 ISSN: 2202-9648 Nonviolence Centre Australia dedicates 30th January, Martyrs’ Day to all those Martyrs who were sacrificed for their just causes. I have nothing new to teach the world. Truth and Non-violence are as old as the hills. All I have done is to try experiments in both on as vast a scale as I could. -Mahatma Gandhi February 2016 | Non-Violence News | 1 Mahatma Gandhi’s 5 Teachings to bring about World Peace “If humanity is to progress, Gandhi is inescapable. He lived, with lies within our hearts — a force of love and thought, acted and inspired by the vision of humanity evolving tolerance for all. Throughout his life, Mahatma toward a world of peace and harmony.” - Dr. Martin Luther Gandhi fought against the power of force during King, Jr. the heyday of British rein over the world. He transformed the minds of millions, including my Have you ever dreamed about a joyful world with father, to fight against injustice with peaceful means peace and prosperity for all Mankind – a world in and non-violence. His message was as transparent which we respect and love each other despite the to his enemy as it was to his followers. He believed differences in our culture, religion and way of life? that, if we fight for the cause of humanity and greater justice, it should include even those who I often feel helpless when I see the world in turmoil, do not conform to our cause. History attests to a result of the differences between our ideals. -

Career Guide Career Guide Professionals Career Guide Publications Career Guidance Standards

Career guide A career guide is an individual or publication that provides guidance to people facing a variety of career challenges. These challenges may include (but are not limited to) dealing with redundancy; seeking a new job; changing careers; returning to work after a career break; building new skills; personal and professional development; going for promotion; and setting up a business. The common aim of the career guide, whatever the particular situation of the individual being guided, is normally to help that individual gain control of their career and, to some extent, their life. Career guide professionals Individuals who work as career guides usually take the approach of combining coaching, mentoring, advising and consulting in their work, without being limited to any one of these disciplines. A typical career guide will have a mixture of professional qualifications and work experiences from which to draw when guiding clients.[1] They may also have a large network of contacts and, when appropriate will put a particular client in touch with a contact relevant to their case. A career guide may work for themselves independently or for one or more private or public careers advisory services. The term 'Career Guide' has been first established and used by career consulting firm Position Ignition, which was created in 2009 and has been using the term for their career consultants and career advisors. Career guide publications Career guide publications may take a number of forms, including PDFs, booklets, journals or books. A career guide publication will typically be divided up into a number of chapters or segments, each one addressing a particular career issue. -

A Jurisprudence of Nonviolence

A Jurisprudence of Nonviolence YXTA MAYA MURRAYt Is there a way we could theorize about law that would make the world a less violent place? In the 1980s, cultural, or "different voice," feminist legal theory seemed poised to take up the mantles of Mohandas Gandhi and Martin Luther King by incorporating nonviolent values into society and the law. Based on the work of psychologist Carol Gilligan, cultural feminist legal theory valorizes the supposedly female virtues of caretaking and connectivity.' As elaborated by theorists such as Robin West, 2 Martha Minow, Joan Williams, and Christine Littleton,5 it also celebrates women's "ethic of care," which is a brand of moral reasoning that emphasizes empathy, particulars, and human relationships, as opposed to men's "standard of justice," which stresses individualism, abstraction, and autonomy. 6 Though these cultural feminists wrote on issues such as employment law7 and family law,8 their ideas about caring also promised to transform criminal law, Second Amendment jurisprudence, and international law. Indeed, no other jurisprudential school of thought appeared as well equipped to craft a legal theory of peace.9 As we all Professor of Law, Loyola Law School-Los Angeles. B.A., University of California Los Angeles; J.D., Stanford University. A warm and loving thanks to all the members of Movie Nite: Allan Ides, David Leonard, and Victor Gold, who all helped usher this article to publication. I also benefited from the generous and brilliant help of Francisco Valdes and Angela Harris, two wonderful colleagues in legal education. Thank you. See, e.g., CAROL GILLIGAN, IN A DIFFERENT VOICE: PSYCHOLOGICAL THEORY AND WOMEN'S DEVELOPMENT 167-68 (1982). -

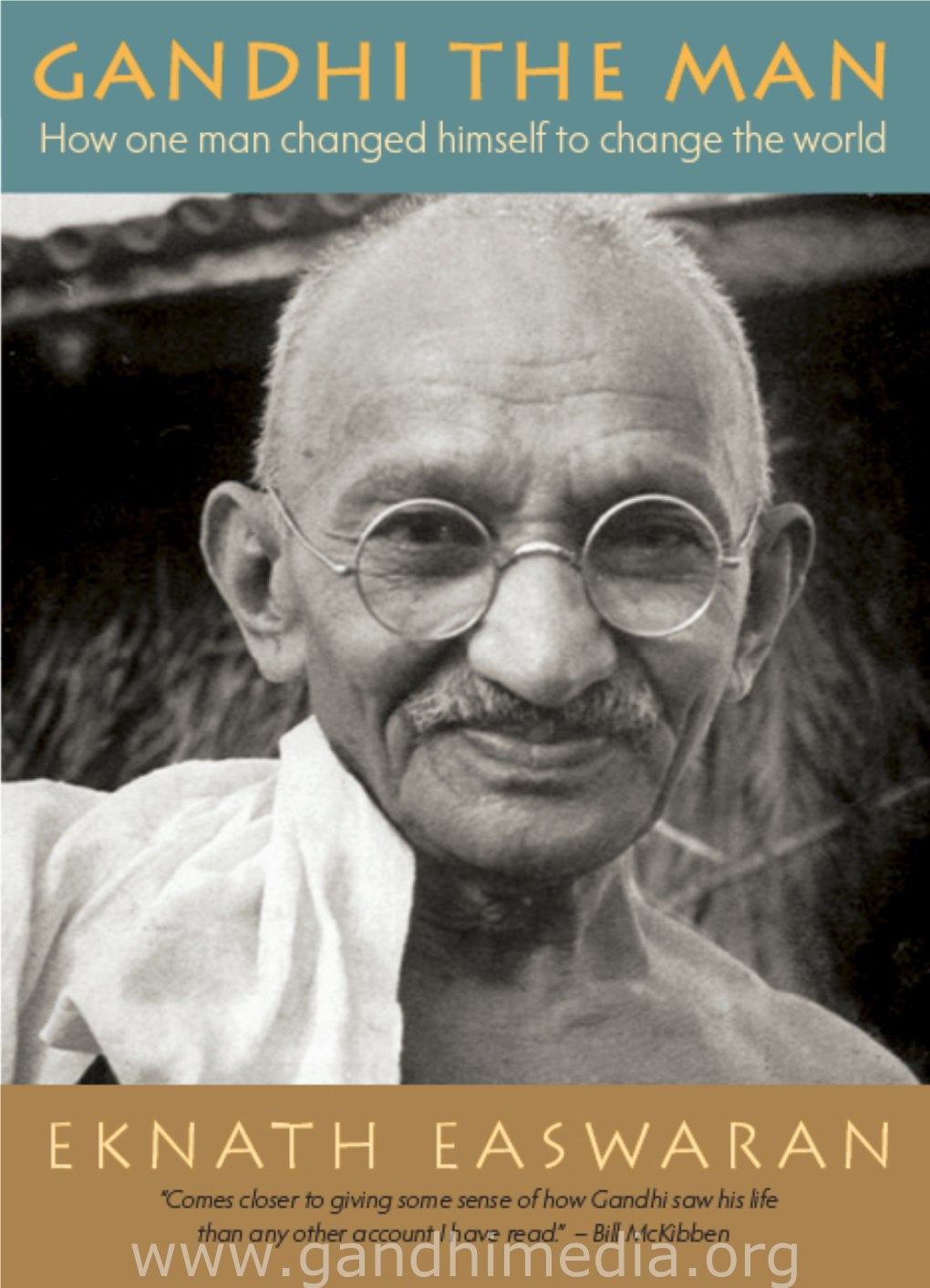

Eknath Easwaran Classics of Indian Spirituality Special Birth Centenary Editions Forthcoming

24 Eknath Easwaran Classics of Indian Spirituality Special Birth Centenary Editions Forthcoming Bhagavad Gita Upanishads Includes Includes This book places the Gita in its historical setting In this ancient wisdom text the illumined and brings out the universality and timelessness of sages share insight, the results of their its teachings. investigation into consciousness itself. J-1989 DVD Rs.350 296p ISBN 978-81-8495-071-7 J-1990 DVD Rs.350 384p ISBN 978-81-8495-072-4 Eknath Easwaran, Founder and Director of the Blue Mountain Center of Meditation and the Nilgiri Press, taught the classics of world mysticism and meditation from 1960 till his death in 1999. His method of meditation has a practical appeal which enables ordinary people to translate lofty ideals into daily living within the context of any religious tradition. Religion & Philosophy 25 These timeless, universal classics from traditional Indian wisdom address the fundamental questions of life. Speaking to us directly, spiritual teachers assure us that if we make wise choices, everything that matters in life is within human reach. Dhammapada ALSO AVAILABLE 7 Dialogue with Death Includes 1 The Bhagavad J-959 Rs.225 240p ISBN 81-7224-757-5 Gita for Daily Living 8 Your Life is Your Message 3 Volumes J-1121 Rs.125 126p JH-257 HB Rs.1,800 ISBN 81-7224-986-1 ISBN 81-7224-616-1 J-1000 PB Rs.795 9 ISBN 81-7224-818-0 Love is God J-1220 Rs.175 234p ISBN 81-7992-154-9 10 God Makes the Rivers to Flow J-1361 Rs.250 336p ISBN 81-7992-330-4 11 The Constant Companion J-1485 Rs.295 296p ISBN 81-7992-507-2 12 Words to Live By J-1539 Rs.295 400p ISBN 81-7992-570-6 2 Living Thoughts of 13 Great People Strength in the Storm The Dhammapada, a collection of the Buddha’s J-763 Rs.250 384p teachings, means “the path of dharma,” the path of ISBN 81-7224-427-4 J-1552 Rs.225 184p ISBN 81-7992-583-8 truth, harmony, and righteousness that anyone can 3 Gandhi the Man 14 follow to reach the highest good.