At First Glance It May Appear That the Denver Mountain Parks Are Unrelated Parcels Scattered Across Four Counties. but the Reali

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

National Register of Historic Places Registration Form

NPS Form 10-900 B No. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JAN 2 3 I995 National Register of Historic Places Registration Form INTERAGENCY RESOURCES DIVISION NATIONAL PARK SERVICE This form is for use in nominating or requesting determination for individual instruction in How to Complete (National Register Bulletin lete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering, the information requested."If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter N/A" for "not applicable." Tor functions, architectural classification, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NFS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name ____ ECHO LAKE PARK other names/site number _________________5CC646 2. Location street & number ALONG STATE HIGHWAYS 103 AND 5 __________ [N/A] not for publication city or town IDAHO SPRINGS __________________ [ X ] vicinity state Colorado code CO county CLEARCREEK code 019 zip code 80452 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act. as amended, I hereby certify that this &O nomination T ] request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR Part 60. In my opinion, the property 1$ meets [ ] does not meet the National Register criteria. I recommend that this property be "ppektered significant [ ] nationally [ ] statewide [X locally. -

Copyrighted Material

20_574310 bindex.qxd 1/28/05 12:00 AM Page 460 Index Arapahoe Basin, 68, 292 Auto racing A AA (American Automo- Arapaho National Forest, Colorado Springs, 175 bile Association), 54 286 Denver, 122 Accommodations, 27, 38–40 Arapaho National Fort Morgan, 237 best, 9–10 Recreation Area, 286 Pueblo, 437 Active sports and recre- Arapaho-Roosevelt National Avery House, 217 ational activities, 60–71 Forest and Pawnee Adams State College–Luther Grasslands, 220, 221, 224 E. Bean Museum, 429 Arcade Amusements, Inc., B aby Doe Tabor Museum, Adventure Golf, 111 172 318 Aerial sports (glider flying Argo Gold Mine, Mill, and Bachelor Historic Tour, 432 and soaring). See also Museum, 138 Bachelor-Syracuse Mine Ballooning A. R. Mitchell Memorial Tour, 403 Boulder, 205 Museum of Western Art, Backcountry ski tours, Colorado Springs, 173 443 Vail, 307 Durango, 374 Art Castings of Colorado, Backcountry yurt system, Airfares, 26–27, 32–33, 53 230 State Forest State Park, Air Force Academy Falcons, Art Center of Estes Park, 222–223 175 246 Backpacking. See Hiking Airlines, 31, 36, 52–53 Art on the Corner, 346 and backpacking Airport security, 32 Aspen, 321–334 Balcony House, 389 Alamosa, 3, 426–430 accommodations, Ballooning, 62, 117–118, Alamosa–Monte Vista 329–333 173, 204 National Wildlife museums, art centers, and Banana Fun Park, 346 Refuges, 430 historic sites, 327–329 Bandimere Speedway, 122 Alpine Slide music festivals, 328 Barr Lake, 66 Durango Mountain Resort, nightlife, 334 Barr Lake State Park, 374 restaurants, 333–334 118, 121 Winter Park, 286 -

1920S Small Homes Survey Report

Discover Denver Know It. Love It. One Building at a Time. Survey Report Pilot Area #2 1920s Small Homes Park Hill, Harkness Heights, Grand View Prepared By: Jessica Aurora Ugarte and Beth Glandon Historic Denver, Inc. 1420 Ogden Street, #202 Denver, CO 80218 Rev. May 4, 2015 With Support From: 1 Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................................... 4 Funding Acknowledgement ............................................................................................................................... 4 Project Areas .............................................................................................................................................................. 5 Research Design & Methods ...................................................................................................................................... 7 Historic Context ....................................................................................................................................................... 10 Context, Theme and Property Type ......................................................................................................................... 18 Results ...................................................................................................................................................................... 19 Data ..................................................................................................................................................................... -

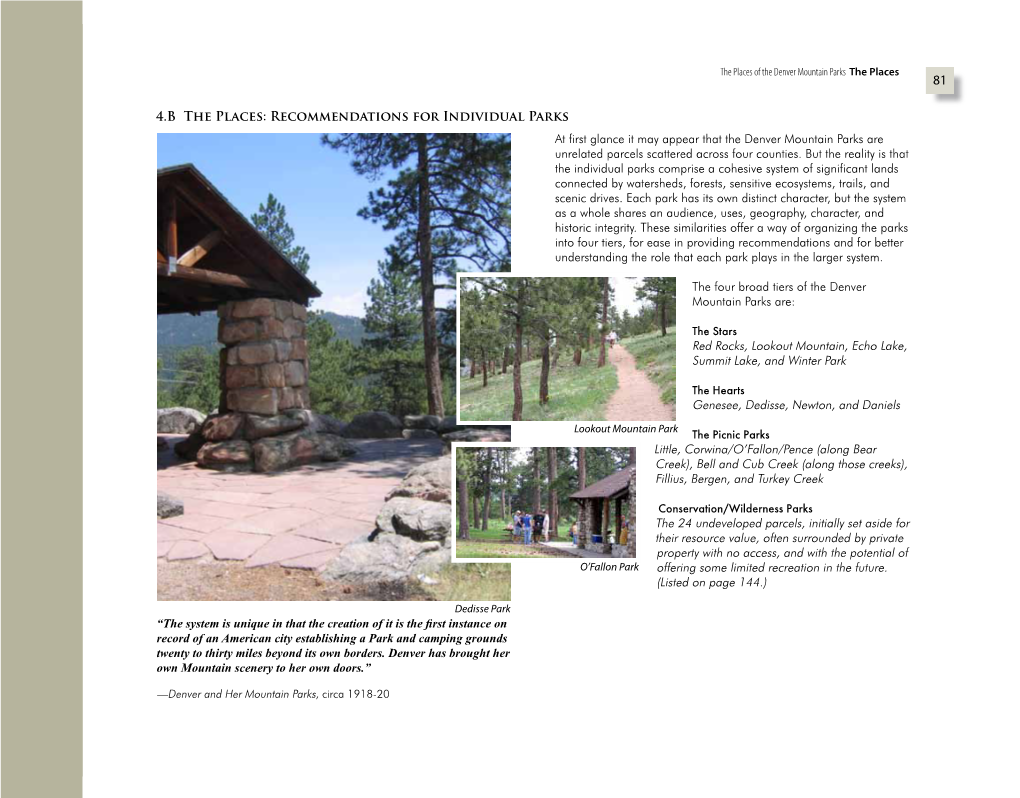

Chapter 4 the Denver Mountain Parks System 56

Chapter 4 The Denver Mountain Parks System 56 The Denver Mountain Parks System The Denver Mountain Parks The System 57 Chapter 4 The Denver Mountain Parks System 4.A. Systemwide Recommendations Recreation Recommendations Background Today, those who visit the Denver Mountain Parks (DMP) represent a broad cross section of people in demographics, where they reside, and how far they travel to enjoy these mountain lands. Visitors to the Mountain Parks are cosmopolitan – a true mix of cultures and languages. With the exception of African-Americans being under- represented, the Mountain Parks reflect the same diversity of age and ethnicity as occurs at Denver’s urban parks. Although visitors to the Mountain Parks represent the spectrum, many come from low to middle income households. Typically one third of those who visit either a Denver Mountain Park or another county open space park are Denver residents. Another third reside in the county in which the park is located. The last third are visitors from other counties along the Front Range, visitors from other parts of the state and nation, and international visitors. Together, mountain open space lands owned by Denver, Jefferson County, Douglas County, and Clear Creek County are used recipro- cally. Together, they are a regional Front Range open space sys- tem where each county provides its own lands and facilities for the enjoyment of its own residents, recognizing that these lands are also enjoyed by all visitors. The goal for Denver Mountain Parks is to provide the amenities and programs that take advantage of but do not diminish the valu- Red Rocks Park able natural and cultural resources and that meet today’s recre- ation needs and desire to connect kids with nature. -

Denver Mountain Parks: Echo Lake Park 2

1.Title / Content Area: Denver Mountain Parks: Echo Lake Park 2. Historic Site: Echo Lake Park 3. Developed by: Century Middle School Educators rd th 4. Grade Level and Grade Level: 3 – 5 Standards: Colorado Social Studies Standards 1-4 Standards: Prepared Graduate Competencies: Content in this Document Based Question ( DBQ ) link to Prepared Graduate Competencies in the Colorado Academic Standards rd 3 : PGC 1-5, 7 t h 4 : PGC 1-5, 7 t h 5 : PGC 1-5, 7 5. Assessment Question: Why is the lodge at Echo Lake significant historically and architecturally, and why is it important today? 6. Contextual Paragraph Echo Lake Park was established in 1921 but the idea for the park was first coined in 1901 as the National Park and Wilderness movements were just beginning in the United States. The park was designed as part of an extension of the Denver Mountain Parks project which followed the Olmsted plan already in place for the parks. In 1916, trails in the wilderness area were developed by the National Park Service to allow public access and recreation. In 1921, as a result of a Supreme Court decision that allowed cities to condemn property outside of their normal jurisdiction, Denver acquired 600 acres in the area which included the lake. In 1926, Jules Jacques Benoit Benedict designed a lodge in the Mountain Rustic Style which incorporated local stone and wood, and reflected the mountain landscape and setting. An ice house was also built in the same style in 1926, and later the Civilian Conservation Corps constructed both a stone pavilion and a rectangular shaped stone concession stand as part of the park complex. -

Denver's Mountain Parks Foundation Kicks Off Capital Campaign

Est. 1970 + Vol ume 45 + Number 4 + fall 2016 The picnic shelter in Filius Park is an excellent example of the Denver Mountain Parks rustic architectural style. Many of these shelters have been neglected and are now in severe disrepair. Photo courtesy: Denver Public Library, Western History Collection Denver’s Mountain Parks Foundation Kicks Off Capital Campaign By Becca Dierschow, Preservation and Research Coordinator was a bold move, but one that the voters of Denver heartily supported. In 1912, In 1916, Denver released a series of tourism booklets promoting the newly the citizens of Denver passed a mill levy that funded the purchase and maintenance formed Denver Mountain Parks system. These 18 page, full color pamphlets of the parks system until 1955. illustrate many features of the Mountain Parks system that are well-known today To create a master plan for the proposed system, Denver tapped the most – Bergen Park, the winding Lariat Loop leading up to Lookout Mountain, and the prominent landscape architecture firm in the country – the Olmsted Brothers. The buffalo herd grazing in Genesee Park. All of these amenities, the pamphlets boast- sons of renowned landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, John and Frederick ed, were an easy car ride from Denver. Picnic shelters, fire pits, and well houses Jr carried on their father’s legacy and vastly expanded the firm’s reputation in their welcomed visitors and provided a place of respite from city living. own right. Frederick Olmsted Jr came to Denver in 1912 to oversee the planning The Denver Mountain Parks system was first proposed as early as 1901, as of the Denver Zoo, Civic Center, and City Park, along with the city-wide parkways part of a state-wide trend of preserving natural landscapes for the benefit of urban system. -

Municipal Parks Parkways

MMuunniicciippaall PPaarrkkss aanndd PPaarrkkwwaayyss IN THE CCOOLLOORRAADDOO SSTTAATTEE RREEGGIISSTTEERR OF HHIISSTTOORRIICC PPRROOPPEERRTTIIEESS Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Colorado Historical Society DIRECTORY OF MMuunniicciippaall PPaarrkkss aanndd PPaarrkkwwaayyss IN THE CCOOLLOORRAADDOO SSTTAATTEE RREEGGIISSTTEERR OOFF HHIISSTTOORRIICC PPRROOPPEERRTTIIEESS Includes Colorado properties listed in the National Register of Historic Places and the State Register of Historic Properties Updated Through December 2006 Prepared By Lisa Werdel © 2006 Office of Archaeology and Historic Preservation Colorado Historical Society 1300 Broadway Denver, Colorado 80203-2137 www.coloradohistory-oahp.org The Colorado State Register of Historic Properties is a program of the Colorado Historical Society. Founded in 1879, the Colorado Historical Society brings the unique character of Colorado's past to more than a million people each year through historical museums and highway markers, exhibitions, manuscript and photograph collections, popular and scholarly publications, historical and archaeological preservation services, and educational programs for children and adults. The Society collects, preserves, and interprets the history of Colorado for present and future generations. A nonprofit agency with its own membership, the Society is also a state institution located within Colorado's Department of Higher Education The Colorado Historical Society operates twelve historic sites and museums at ten locations around the state, including -

Central Mountains Area Plan 1 Introduction This Area Plan Is an Update to the 1994 Central Mountains Community Plan

Jefferson County Comprehensive Master Plan Table of Contents 2 Introduction 2 History 10 Demographics 10 Land Use Recommendations 16 General Policies 30 Maps Jefferson County Comprehensive Master Plan - Central Mountains Area Plan 1 Introduction This Area Plan is an update to the 1994 Central Mountains Community Plan. The creation of the Central Mountains Community Plan started in June of 1989, and involved rigorous participation from a Community Advisory Group comprised of 13 people, chosen by the Board of County Commissioners as representatives of the community. The update of this Plan was started by Jefferson County Planning and Zoning Staff in the spring of 2012 with the intent of incorporating the Community Plan into the Comprehensive Master Plan. Seven public meetings were held throughout the update process to gather comments on the Plan. The goal of the update was to re-evaluate the existing conditions related to land use and then create a land use recommendation map and policies that are specific to the Central Mountains area. The recommendations in this Central Mountains Area Plan supersede the recommendations in the Central Mountains Community Plan. This Plan is shorter than the 1994 plan because any goals or policies that were duplicated in the Comprehensive Master Plan have been removed. This Plan now only contains information, land use recommendations, and policies specific to the Central Mountains Area. History The history of the Central Mountain community with its three canyons Mt. Vernon, Bear Creek and Clear Creek is rich with memories of Colorado’s early mining days. That these canyons are the “Gateways to the Rockies” is a statement just as true today as it was in 1859 when miners began haul- ing their equipment up the old Ute Indian trails to the gold mining near Idaho Springs, Central City, Leadville and Breckenridge. -

C Lear Creek GIS C Ounty

Creek G ilpin C o unty D D D 12147 D Jefferson County G ty Gilpin County rand Coun ICE LAKE D OHMAN LAKE STEUART LAKE D D REYNOLDS LAKE D D 13391 LAKE CAROLINELOCH LOMAND ST MARYS GLACIER Fox Mountain ST MARYS DLAKE FALL RIVER SILVER LAKE D D LAKE QUIVIRA 11239 13130 FALL RIVER RESERVOIR SLATER LAKE D SILVER CREEK SHERWIN LAKECHINNS LAKE Witter Peak D D 12884 D D James Peak Wilderness MEXICAN GULCH D ETHEL LAKEBYRON LAKE D D BILL MOORE LAKE HAMLIN GULCH D D 13132 CUMBERLAND GULCH D MILL CREEK D D Russell Peak Breckinridge Peak Berthoud Pass D D 12889 G D D ilp D in D C D ou n ty D Grand C D D ounty D MAD CREEK LION CREEK D Stanley Mountain YORK GULCH D D FALL RIVER 12521 BLUE CREEK Cone Mountain D D HOOP CREEK 12244 SPRING GULCH Red Elephant Hill D 10316 D ¤£US 40 D CLEAR CREEK This map is visual representation only, do not use Bellevue Mountain URAD RESERVOIR (LOWER) for legal purposes. Map is not survey accurate and ¨¦§I 70 D WEST FORK CLEAR CREEK 9863 Seaton Mountain may not comply with National Mapping Accuracy Red Mountain D D GUANELLA RESERVOIR 9105 12315 EMPIRE n County Standards. Map is based on best available data as Gilpi RUBY CREEK Ball Mountain Douglas Mountain of October, 2018 . BUTLER GULCH CENTRAL CITY D D VIRGINIA CANYON Lincoln Mountain GEORGIA GULCH 12529 9550 OHIO GULCH WOODS CREEK D GILSON GULCH Engelmann Peak 10363 TURKEY GULCH D IDAHO HASSELL LAKEURAD RESERVOIR (UPPER) 13362 BARD CREEK LAKE SILVER CREEK TRAIL CREEK J e US 6 f f ¤£ e r s o BARD CREEK SPRINGS n Flirtation Peak C Robeson Peak Columbia Mountain o ty -

Botrychium Echo WH Wagner

Botrychium echo W.H. Wagner (reflected grapefern): A Technical Conservation Assessment Prepared for the USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region, Species Conservation Project July 22, 2004 David G. Anderson and Daniel Cariveau Colorado Natural Heritage Program 8002 Campus Delivery — Colorado State University Fort Collins, CO 80523 Peer Review Administered by Center for Plant Conservation Anderson, D.G. and D. Cariveau (2004, July 22). Botrychium echo W.H. Wagner (reflected grapefern): a technical conservation assessment. [Online]. USDA Forest Service, Rocky Mountain Region. Available: http:// www.fs.fed.us/r2/projects/scp/assessments/botrychiumecho.pdf [date of access]. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was greatly facilitated by the helpfulness and generosity of many experts, particularly Don Farrar, Cindy Johnson-Groh, Warren Hauk, Peter Root, Dave Steinmann, Florence Wagner, and Loraine Yeatts. Their interest in the project and time spent answering our questions were extremely valuable. Dr. Kathleen Ahlenslager provided valuable assistance and literature. The Natural Heritage Program/Natural Heritage Inventory/Natural Diversity Database Botanists we consulted (Ben Franklin, Bonnie Heidel) were also extremely helpful. Greg Hayward, Gary Patton, Jim Maxwell, Andy Kratz, Beth Burkhart, and Joy Bartlett assisted with questions and project management. Jane Nusbaum, Carmen Morales, Betty Eckert, Candyce Jeffery, and Barbara Brayfield provided crucial financial oversight. Others who provided information and assistance include Annette Miller, Dave Steinmann, Janet Wingate, and Loraine Yeatts. Loraine Yeatts provided the excellent photograph of Botrychium echo for use in this document. Janet Wingate granted permission to use the illustration of B. echo, and Dave Steinmann provided the photograph of Botrychium habitat. We are grateful to the Colorado Natural Heritage Program staff (Fagan Johnson, Jim Gionfriddo, Jill Handwerk, and Susan Spackman) who reviewed the first draft of this document, and to the two anonymous peer reviewers for their excellent suggestions. -

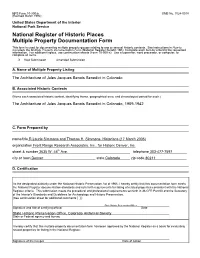

National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form

NPS Form 10-900-b OMB No. 1024-0018 (Revised March 1992) United States Department of the Interior National Park Service National Register of Historic Places Multiple Property Documentation Form This form is used for documenting multiple property groups relating to one or several historic contexts. See instructions in How to Complete the Multiple Property Documentation Form (National Register Bulletin 16B). Complete each item by entering the requested information. For additional space, use continuation sheets (Form 10-900-a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. X New Submission Amended Submission A. Name of Multiple Property Listing The Architecture of Jules Jacques Benois Benedict in Colorado B. Associated Historic Contexts (Name each associated historic context, identifying theme, geographical area, and chronological period for each.) The Architecture of Jules Jacques Benois Benedict in Colorado, 1909-1942 C. Form Prepared by name/title R.Laurie Simmons and Thomas H. Simmons, Historians (17 March 2005) organization Front Range Research Associates, Inc., for Historic Denver, Inc. street & number 3635 W. 46th Ave. telephone 303-477-7597 city or town Denver state Colorado zip code 80211 D. Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966, I hereby certify that this documentation form meets the National Register documentation standards and sets forth requirements for listing of related properties consistent with the National Register criteria. This submission -

M a S T E R P L

MASTER PLAN 2008 2 Acknowledgments Mayor John W. Hickenlooper Kevin Patterson, Manager of Denver Parks and Recreation Bart Berger, President of the Denver Mountain Parks Foundation Gary Walter, Douglas County Public Works Primary authors: Bert Weaver, Clear Creek County Susan Baird, Tina Bishop Denver City Council Members: Dave Webster, President, Inter-Neighborhood Cooperation Carol Boigan Tom Wooten, Ross Consulting Charlie Brown Melanie Worley, Douglas County Commissioner Editors: Jeanne Faatz Dick Wulf, Director, Evergreen Park & Recreation District Sally White, Susan Baird Rick Garcia Frank Young, Clear Creek Open Space Michael Hancock Marcia Johnson Contributing authors and editors: Peggy Lehmann Roundtable Experts: Bart Berger, Jude O’Connor, A.J. Tripp-Addison Doug Linkhart Anne Baker-Easley, Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado Paul D. López Deanne Buck, Access Fund Thanks to: Curt Carlson, Colorado Parks & Recreation Association Carla Madison Barnhart Communications, Denver Mountain Parks Judy Montero Erik Dyce, Theatres and Arenas Foundation, and The Parks People. Chris Nevitt Colleen Gadd, Jefferson County Open Space Jeanne Robb Mark Guebert-Stewart, Recreational Equipment, Inc. Karen Hardesty, Colorado Division of Wildlife Photos: Fabby Hillyard, LODO District Historic photos courtesy of the Denver Public Library Western History Master Plan Advisory Group: Diane Hitchings, USDA Forest Service Collection (DPL-WHC), Barbara Teyssier Forrest Collection, and Denver Mountain Parks file photos. Co-chair Peggy Lehmann, Denver City Councilwoman Gerhard Holtzendorf, Recreational Equipment, Inc. Co-chair Landri Taylor Tim Hutchens, Denver Parks & Recreation, Outdoor Rec Other photos contributed by Susan Baird, Bart Berger, Tina Bishop, Cheryl Armstrong, CEO, Beckwourth Mt. Club Michelle Madrid-Montoya, Denver Parks & Recreation Michael Encinias, Micah Klaver, Bill Mangel, Jessica Miller, Pat Mundus, Tad Bowman, Theatres and Arenas Bryan Martin, Colorado Mountain Club Jude O’Connor, Glen Richardson, Ken Sherbenou, Mike Strunk, A.J.