A Brief History of the Future

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Engineering of Computer Networking Protocols : an Historical Perspective Gregor V

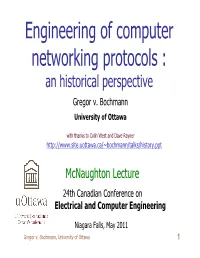

Engineering of computer networking protocols : an historical perspective Gregor v. Bochmann University of Ottawa with thanks to Colin West and Dave Rayner http://www.site.uottawa.ca/~bochmann/talks/history.ppt McNaughton Lecture 24th Canadian Conference on Electrical and Computer Engineering Niagara Falls, May 2011 Gregor v. Bochmann, University of Ottawa 1 Approximate time line 1960: first high-level programming languages 1965: time sharing operating systems and interactive terminals 1970: first experimental computer networks 1975: X.25 networking standard, proprietary networking architectures, e.g. IBM’s SNA 1980: experimental Internet, OSI standardization started, Teletex (a kind of Web service, Telidon in Canada) 1985: Formal Description Techniques (FDTs) developed, experimental tools 1990: commercial SDL tools, beginning of public use of the Internet and Web 1995: Java released, wide use of the Internet, digital wireless telephony spreads – UML (universal modeling language) 2000: XML and Web Services 2005: beginning integration of wireless services with the Internet 2011: there we are . Gregor v. Bochmann, University of Ottawa 2 Computer communications in the 1970ies Remote access to servers User terminals Batch entry terminals Line multiplexing line speed: 300 bps Link protocols (with sequence numbering) Alternating bit protocol (1969) Bisync, SDLC (IBM) Gregor v. Bochmann, University of Ottawa 3 Computer communications in the 1970ies Computer networks ARPANET (USA): first long distance computer network – first trial in 1969 NPL network (UK): first LAN Cyclade (France): introduced IP service at the network layer – around 1972 Donald Davies, NPL Leonard Kleinrock, UCLA Louis Pouzin with ARPAnet node INRIA (France) Gregor v. Bochmann, University of Ottawa 4 Computer communications in the 1970ies Protocol standards First network protocol standard: X.25 Vendor networking architectures IBM (SNA), DEC, Honeywell, etc. -

Growth of the Internet

Growth of the Internet K. G. Coffman and A. M. Odlyzko AT&T Labs - Research [email protected], [email protected] Preliminary version, July 6, 2001 Abstract The Internet is the main cause of the recent explosion of activity in optical fiber telecommunica- tions. The high growth rates observed on the Internet, and the popular perception that growth rates were even higher, led to an upsurge in research, development, and investment in telecommunications. The telecom crash of 2000 occurred when investors realized that transmission capacity in place and under construction greatly exceeded actual traffic demand. This chapter discusses the growth of the Internet and compares it with that of other communication services. Internet traffic is growing, approximately doubling each year. There are reasonable arguments that it will continue to grow at this rate for the rest of this decade. If this happens, then in a few years, we may have a rough balance between supply and demand. Growth of the Internet K. G. Coffman and A. M. Odlyzko AT&T Labs - Research [email protected], [email protected] 1. Introduction Optical fiber communications was initially developed for the voice phone system. The feverish level of activity that we have experienced since the late 1990s, though, was caused primarily by the rapidly rising demand for Internet connectivity. The Internet has been growing at unprecedented rates. Moreover, because it is versatile and penetrates deeply into the economy, it is affecting all of society, and therefore has attracted inordinate amounts of public attention. The aim of this chapter is to summarize the current state of knowledge about the growth rates of the Internet, with special attention paid to the implications for fiber optic transmission. -

Sunday Morning Grid 6/22/14 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 6/22/14 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Morning (N) Å Face the Nation (N) Paid Program High School Basketball PGA Tour Golf 4 NBC News Å Meet the Press (N) Å Conference Justin Time Tree Fu LazyTown Auto Racing Golf 5 CW News (N) Å In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News (N) Wildlife Exped. Wild 2014 FIFA World Cup Group H Belgium vs. Russia. (N) SportCtr 2014 FIFA World Cup: Group H 9 KCAL News (N) Joel Osteen Mike Webb Paid Woodlands Paid Program 11 FOX Paid Joel Osteen Fox News Sunday Midday Paid Program 13 MyNet Paid Program Crazy Enough (2012) 18 KSCI Paid Program Church Faith Paid Program 22 KWHY Como Paid Program RescueBot RescueBot 24 KVCR Painting Wild Places Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Oil Painting Kitchen Mexican Cooking Cooking Kitchen Lidia 28 KCET Hi-5 Space Travel-Kids Biz Kid$ News LinkAsia Healthy Hormones Ed Slott’s Retirement Rescue for 2014! (TVG) Å 30 ION Jeremiah Youssef In Touch Hour of Power Paid Program Into the Blue ›› (2005) Paul Walker. (PG-13) 34 KMEX Conexión En contacto Backyard 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA Grupo H Bélgica contra Rusia. (N) República 2014 Copa Mundial de FIFA: Grupo H 40 KTBN Walk in the Win Walk Prince Redemption Harvest In Touch PowerPoint It Is Written B. Conley Super Christ Jesse 46 KFTR Paid Fórmula 1 Fórmula 1 Gran Premio Austria. -

OECD Observer Celebrates 50 Meeting the Global Water Challenge

Norway’s gender experience Euro area: Why solidarity matters Israel’s progress report Special focus: Policymaking and the information revolution No 293 Q4 2012 www.oecdobserver.org OECD Observer celebrates 50 Meeting the global water challenge Nestlé’s Aman Bajaj Sood (left) and farmer Harinder Kaur take part in a Farmer Water Awareness Programme provided near the Nestlé factory in Moga, India. Through our Creating Shared Alongside our other CSV key > Public policy Value reporting, we aim to share focus areas of nutrition and > Collective action information about our long-term rural development, this year’s > Direct operations impact on society and how this report summarises Nestlé’s > Supply chain is linked to the creation of our response to the water challenge > Community engagement long-term business success. in five key areas: Visit the CSV Section of our website for a complete report of our progress, challenges and performance in 2011 www.nestle.com /csv CONTENTS No 293 Q4 2012 Meeting the global water challenge READERS’ VIEWS 20 Combating terrorist fi nancing in the 2 Corporate tax responsibility; Labour advice information age Rick McDonell, Executive Secretary, EDITORIAL Financial Action Task Force 3 From the information revolution to 21 Africa.radio a knowledge-based world Roman Rollnick, Chief Editor, Advocacy, Angel Gurría Outreach and Communications, UN-Habitat 22 Is evidence evident? NEWS BRIEF Anne Glover, Chief Scientifi c Adviser to the 4 Crisis drives up social spending–as tax President of the European Commission revenues -

Five Celebrity Chefs Immortalized on Limited Edition Forever Stamps

Sept. 26, 2014 Chicago Contact: Mark V. Reynolds [email protected] 312-351-5868 National: Mark Saunders 202-268-6524 [email protected] usps.com/news Five Celebrity Chefs Immortalized On Limited Edition Forever Stamps To obtain high-resolution stamp images for media use only, email: [email protected] CHICAGO — The Postal Service cooked up a feast of 20 million Limited Edition Celebrity Chefs Forever stamps today. The sugar-free, fat-free, zero-calorie stamps will be on the menu of the nation’s Post Offices beginning today. The five chefs honored on the stamps — James Beard, Julia Child, Joyce Chen, Edna Lewis and Edward (Felipe) Rojas-Lombardi — revolutionized the nation’s understanding of food. By integrating international ingredients and recipes with American cooking techniques and influence, these chefs introduced new foods and flavors to the American culture. “These chefs invited us to feast on regional and international flavors and were early — and ardent — champions of trends that many foodies now take for granted,” said U.S. Postal Service Entry Mail and Payment Technology Vice President Pritha Mehra in dedicating the stamps. Mehra is the owner of the Mystic Kitchen cooking school where she teaches the art of Indian cooking to students throughout the Washington, D.C. metropolitan area. “As they shared their know-how, they encouraged us to undertake our own culinary adventures, and American kitchens have never been the same since. That is why today, we are celebrating not only five celebrity chefs, but also the unique flavors and dishes that — thanks to them — have become American staples,” she added. -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT 2013 Archive Name ATAS14_Corp_140003273 MECH SIZE 100% PRINT SIZE Description ATAS Annual Report 2014 Bleed: 8.625” x 11.1875” Bleed: 8.625” x 11.1875” Posting Date May 2014 Trim: 8.375” x 10.875” Trim: 8.375” x 10.875” Unit # Live: 7.5” x 10” LIve: 7.5” x 10” message from THE CHAIRMAN AND CHIEF EXECUTIVE OFFICER At the end of 2013, as I reflected on my first term as Television Academy chairman and prepared to begin my second, it was hard to believe that two years had passed. It seemed more like two months. At times, even two weeks. Why? Because even though I have worked in TV for more than three decades, I have never seen our industry undergo such extraordinary — and extraordinarily exciting — changes as it has in recent years. Everywhere you turn, the vanguard is disrupting the old guard with an astonishing new technology, an amazing new show, an inspired new way to structure a business deal. This is not to imply that the more established segments of our industry have been pushed aside. On the contrary, the broadcast and cable networks continue to produce terrific work that is heralded by critics and rewarded each year at the Emmys. And broadcast networks still command the largest viewing audience across all of their platforms. With our medium thriving as never before, this is a great time to work in television, and a great time to be part of the Television Academy. Consider the 65th Emmy Awards. The CBS telecast, hosted by the always-entertaining Neil Patrick Harris, drew our largest audience since 2005. -

The Evolution of Internet Evidence 1

Name: Sam Kavande Rocha Enrollment: 2777582 Nombre del curso: Name of professor: Information technologies Tania Zertuche Module: Activity: 1 Evidence 1 Date: 8 / September / 2015 References: The evolution of Internet Evidence 1 1 Table of contents: Introduction Page 2 Topic explanation Page 2 to 3 Conclusions Page 4 Bibliography Page 5 references 2 Introduction: The Internet is evolving. The majority of end-users perceive this evolution in the form of changes and updates to the software and networked applications that they are familiar with, or with the arrival of entirely new applications that change the way they communicate, do business, entertain themselves, and so on. Evolution is a constant feature throughout the network Topic explanation: The history of the Internet begins with the development of electronic computers in the 1950s. Initial concepts of packet networking originated in several computer science laboratories in the United States, Great Britain, and France. The US Department of Defense awarded contracts as early as the 1960s for packet network systems, including the development of the ARPANET (which would become the first network to use the Internet Protocol.) The first message was sent over the ARPANET from computer science Professor Leonard Kleinrock's laboratory at University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA) to the second network node at Stanford Research Institute (SRI). Packet switching networks such as ARPANET, NPL network, CYCLADES, Merit Network, Tymnet, and Telnet, were developed in the late 1960s and early 1970s using a variety of communications protocols. Donald Davies was the first to put theory into practice by 3 designing a packet-switched network at the National Physics Laboratory in the UK, the first of its kind in the world and the cornerstone for UK research for almost two decades. -

I Love to Eat by James Still in Performance: April 15 - June 27, 2021

Commonweal Theatre Company presents I Love To Eat by James Still In performance: April 15 - June 27, 2021 products and markets. Beard nurtured a genera- tion of American chefs and cookbook authors who have changed the way we eat. James Andrew Beard was born on May 5, 1903, in Portland, Oregon, to Elizabeth and John Beard. His mother, an independent English woman passionate about food, ran a boarding house. His father worked at Portland’s Customs House. The family spent summers at the beach at Gearhart, Oregon, fishing, gathering shellfish and wild berries, and cooking meals with whatever was caught. He studied briefly at Reed College in Portland in 1923, but was expelled. Reed claimed it was due to poor scholastic performance, but Beard maintained it was due to his homosexuality. Beard then went on the road with a theatrical troupe. He lived abroad for several years study- ing voice and theater but returned to the United States for good in 1927. Although he kept trying to break into the theater and movies, by 1935 he needed to supplement what was a very non-lucra- Biography tive career and began a catering business. With From the website of the James Beard Founda- the opening of a small food shop called Hors tion: jamesbeard.org/about d’Oeuvre, Inc., in 1937, Beard finally realized that his future lay in the world of food and cooking. nointed the “Dean of American cookery” by In 1940, Beard penned what was then the first Athe New York Times in 1954, James Beard major cookbook devoted exclusively to cock- laid the groundwork for the food revolution that tail food, Hors d’Oeuvre & Canapés. -

Hoping for a Return on Investment in the Cowlitz Pete Caster / [email protected] Judy C

Celebrating the Swedes Large Crowds Flock to Rochester to Let Their Inner Viking Out / Main 3 Hiker Found Dead / Main 5 $1 Early-Week Edition Tuesday, June 24, 2014 Reaching 110,000 Readers in Print and Online — www.chronline.com Hoping for a Return on Investment in the Cowlitz Pete Caster / [email protected] Judy C. Chain sits with her attorney, Sam Experimental Run of Salmon, Net Pens to Yield Better Harvest Groberg, during the irst day of her trial in Lewis County Superior Court on Monday. Trial for ‘Rising Son’ Head Starts ACCUSED: Judy Chafin Faces 30 Felony Charges for Allegedly Collecting $90,000 From Labor and Industries While Running the Controversial Group of Halfway Houses By Stephanie Schendel [email protected] At the peak of the House of the Rising Son organization, Judy Cha- fin ran numerous halfway houses for recently released convicts throughout Pete Caster / [email protected] Lewis County. Mossyrock Fish Hatchery Supervisor Tim Summers feeds fall chinook on Monday morning at the Mayield Net Pen Project at Silver Creek. The Washington De- She collected rent, went grocery partment of Fish and Wildlife is raising nearly 2 million fall chinook in these pins. The ish will eventually be released in the lower Cowlitz River near the salmon shopping for the tenants, enforced hatchery. house rules and dealt with all finan- cial transactions of the business. All FISH STORY: Money Secured in Part by Sen. John the while, she was allegedly collect- Braun Put to Use on Mayfield Lake ing disability checks from the De- partment of Labor and Industries, By Dameon Pesanti claiming she was unable to work. -

The Semantic Web … Sounds Logical!

Rochester Institute of Technology RIT Scholar Works Theses 2004 The Semantic Web … Sounds Logical! Anthony J. Radogna Jr Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.rit.edu/theses Recommended Citation Radogna Jr, Anthony J., "The Semantic Web … Sounds Logical!" (2004). Thesis. Rochester Institute of Technology. Accessed from This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by RIT Scholar Works. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses by an authorized administrator of RIT Scholar Works. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The Semantic Web ... Sounds Logical! By Anthony J. Radogna Jr. Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Thesis Approval Form Student Name: Anthony J. Radogna Thesis Title: Semantic Web, The Future is Upon Us Thesis Committee Name Signature Date Prof. Daniel Kennedy Chair Prof. Michael Axelrod Committee Member Prof. Dianne Bills Committee Member I ( Thesis Reproduction Permission Form Rochester Institute of Technology B. Thomas Golisano College of Computing and Information Sciences Master of Science in Information Technology Semantic Web, The Future is Upon Us I, Anthony J. Radogna, hereby grant permission to the Wallace Library of the Rochester Institute of Technology to reproduce my thesis in whole or in part. Any reproduction must not be for commercial use or profit. Date: ~}:)o loy Signature of Author: I I Table of Contents ABSTRACT 2 INTRODUCTION 4 THE INTERNET PAST AND PRESENT 7 THE SEMANTIC WEB EXPLAINED 10 UNIVERSAL RESOURCE IDENTIFIERS 13 EXTENSIBLE MARKUP LANGUAGE 15 RESOURCE DESCRIPTION FRAMEWORK 19 ONTOLOGIES 24 TRUST AND SECURITY ON THE SEMANTIC WEB 28 CONTENT MANAGEMENT 31 GOALS OF THE SEMANTIC WEB 33 CURRENT STATE 35 CONCLUSION 37 REFERENCES 42 APPENDIX 46 The Semantic Web .. -

Introduction to Bioinformatics (Elective) – SBB1609

SCHOOL OF BIO AND CHEMICAL ENGINEERING DEPARTMENT OF BIOTECHNOLOGY Unit 1 – Introduction to Bioinformatics (Elective) – SBB1609 1 I HISTORY OF BIOINFORMATICS Bioinformatics is an interdisciplinary field that develops methods and software tools for understanding biologicaldata. As an interdisciplinary field of science, bioinformatics combines computer science, statistics, mathematics, and engineering to analyze and interpret biological data. Bioinformatics has been used for in silico analyses of biological queries using mathematical and statistical techniques. Bioinformatics derives knowledge from computer analysis of biological data. These can consist of the information stored in the genetic code, but also experimental results from various sources, patient statistics, and scientific literature. Research in bioinformatics includes method development for storage, retrieval, and analysis of the data. Bioinformatics is a rapidly developing branch of biology and is highly interdisciplinary, using techniques and concepts from informatics, statistics, mathematics, chemistry, biochemistry, physics, and linguistics. It has many practical applications in different areas of biology and medicine. Bioinformatics: Research, development, or application of computational tools and approaches for expanding the use of biological, medical, behavioral or health data, including those to acquire, store, organize, archive, analyze, or visualize such data. Computational Biology: The development and application of data-analytical and theoretical methods, mathematical modeling and computational simulation techniques to the study of biological, behavioral, and social systems. "Classical" bioinformatics: "The mathematical, statistical and computing methods that aim to solve biological problems using DNA and amino acid sequences and related information.” The National Center for Biotechnology Information (NCBI 2001) defines bioinformatics as: "Bioinformatics is the field of science in which biology, computer science, and information technology merge into a single discipline. -

HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007

1 HBO: Brand Management and Subscriber Aggregation: 1972-2007 Submitted by Gareth Andrew James to the University of Exeter as a thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English, January 2011. This thesis is available for Library use on the understanding that it is copyright material and that no quotation from the thesis may be published without proper acknowledgement. I certify that all material in this thesis which is not my own work has been identified and that no material has previously been submitted and approved for the award of a degree by this or any other University. ........................................ 2 Abstract The thesis offers a revised institutional history of US cable network Home Box Office that expands on its under-examined identity as a monthly subscriber service from 1972 to 1994. This is used to better explain extensive discussions of HBO‟s rebranding from 1995 to 2007 around high-quality original content and experimentation with new media platforms. The first half of the thesis particularly expands on HBO‟s origins and early identity as part of publisher Time Inc. from 1972 to 1988, before examining how this affected the network‟s programming strategies as part of global conglomerate Time Warner from 1989 to 1994. Within this, evidence of ongoing processes for aggregating subscribers, or packaging multiple entertainment attractions around stable production cycles, are identified as defining HBO‟s promotion of general monthly value over rivals. Arguing that these specific exhibition and production strategies are glossed over in existing HBO scholarship as a result of an over-valuing of post-1995 examples of „quality‟ television, their ongoing importance to the network‟s contemporary management of its brand across media platforms is mapped over distinctions from rivals to 2007.