Volume VIII, No. 2 Spring 1980 PMS 30 in THIS ISSUE

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Download the Digital Booklet

1 MAIN TITLE 2 THE SMOKING FROG 3 BEDTIME AT BLYE HOUSE 4 NEW CLOTHES FOR QUINT 5 THE CHILDREN'S HOUR 6 PAS DE DEUX 7 LIKE A CHICKEN ON A SPIT 8 ALL THAT PAIN 9 SUMMER ROWING 10 QUINT HAS A KITE 11 PUB PIANO 12 ACT TWO PRELUDE: MYLES IN THE AIR 13 UPSIDE DOWN TURTLE 14 AN ARROW FOR MRS. GROSE 15 FLORA AND MISS JESSEL 16 TEA IN THE TREE 17 THE FLOWER BATH 18 PIG STY 19 MOVING DAY 20 THE BIG SWIM 21 THROUGH THE LOOKING GLASS 22 BURNING DOLLS 23 EXIT PETER QUINT, ENTER THE NEW GOVERNESS; RECAPITULATION AND POSTLUDE MUSIC COMPOSED AND CONDUCTED BY JERRY FIELDING WE DISCOVER WHAT When Marlon Brando arrived in THE NIGHTCOMERS had allegedly come HAPPENED TO THE Cambridgeshire, England, during January into being because Michael Winner wanted to of 1971, his career literally hung in the direct “an art film.” Michael Hastings, a well- GARDENER PETER QUINT balance. Deemed uninsurable, too troubled known London playwright, had constructed a and difficult to work with, the actor had run kind of “prequel” to Henry James’ famous novel, AND THE GOVERNESS out of pictures, steam, and advocates. A The Turn of the Screw, which had been filmed couple of months earlier he had informed in 1961, splendidly, as THE INNOCENTS. MARGARET JESSEL author Mario Puzo in a phone conversation In Hastings’ new story, we discover what that he was all washed up, that no one was happened to the gardener Peter Quint and going to hire him again, least of all to play the governess Margaret Jessel: specifically Don Corleone in the upcoming film version how they influenced the two evil children, of Puzo’s runaway best-seller, The Godfather. -

Indian and Polish Film Festivals

Indian and Polish film festivals articles.latimes.com /2009/apr/16/entertainment/et-screening16 New films from India and Poland are highlighted in the seventh annual Indian Film Festival of Los Angeles and the 10th Polish Film Festival. The Indian Film Festival, which runs Tuesday through April 26, includes five feature films making their world premiere, five making their U.S. premiere and another five making their L.A. debut. The festivities begin with the world premiere of Anand Surapar's "The Fakir of Venice" at the ArcLight Hollywood Cinemas. Ani Kapoor of "Slumdog Millionaire" will also be saluted during the festival with screenings of two of his classic films and the premiere of the English-language version of 2007's "Gandhi, My Father," which he produced. www.indianfilmfestival.org The Polish Film Festival has its gala opening Wednesday at the Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood with a screening of "Perfect Guy for My Girl." It continues through May 3 at Laemmle's Sunset 5 Theatre and other venues in Los Angeles and Orange counties. www .polishfilmla.org -- French composers Two of the late Maurice Jarre's great scores -- for 1985's "Witness" and 1986's "The Mosquito Coast" -- are featured in the American Cinemathque's weekend retrospective "The French Music Composers Go to Hollywood" at the Aero Theatre in Santa Monica. The beautiful music begins tonight with a double bill of 1981's "Woman Next Door," composed by Georges Delerue, and 2001's "Read My Lips," scored by Alexandre Desplat. Michel Legrand supplied the score for 1968's "The Thomas Crown Affair," screening Friday with Michel Colombier's score for 1984's "Against All Odds." The Jarre double feature is scheduled for Saturday. -

RASSEGNA STAMPA DAL 01/04/13 AL 06/06/13 Rassegna Stampa

RASSEGNA STAMPA DAL 01/04/13 AL 06/06/13 Rassegna Stampa Cliente: Romarchè Periodo: dal 01/04/13 al 06/06/13 N° Data Testata Titolo Media Lettori Dimensione Valore Articolo 1 01/04/13 Archeo L'archeologia guarda al futuro stampa 42.900,00 1,00 13.500,00 2 12/04/13 archeologiaviva.it Romarchè: l'archeologia guarda al futuro web 3 22/04/13 professionearcheologo.it Blog News web 4 24/04/13 turismoculturale.it L'archeologia guarda al futuro web 5 29/04/13 archeologiaviva.it Convegni ed eventi web 6 30/04/13 economiadellacultura.it Romarchè l'archeologia guarda il futuro web 7 01/05/13 Archeologia Viva Romarchè stampa 35.000,00 0,13 884,00 8 01/05/13 Plein Air Archeologia, teoria e pratica stampa 87.000,00 0,25 800,00 9 01/05/13 Il Giornale dell'Arte Non solo libri al Salone di Romarchè stampa 22.000,00 0,13 968,50 10 05/05/13 arborsapientiae.com Romarchè 2013 IV Salone dell'editoria archeologica web 11 06/05/13 leggeretutti.net Romarchè l'archeologia guarda il futuro web 12 07/05/13 pbmstoria.it Romarchè web 13 07/05/13 247.libero.it Romarchè l'archeologia guarda il futuro web 14 08/05/13 sotterraneidiroma.it Conferenza stampa di presentazione Romarchè 2013 web 15 08/05/13 archeo.forumfree.it Romarchè: l'archeologia guarda al futuro web 16 08/05/13 blogstreetwire.it Romarchè: l'archeologia guarda al futuro web 17 08/05/13 247.libero.it Romarchè: l'archeologia guarda al futuro web 18 08/05/13 roma‐o‐matic.com Romarchè 2013. -

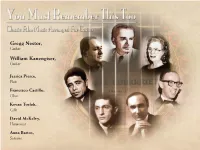

Gregg Nestor, William Kanengiser

Gregg Nestor, Guitar William Kanengiser, Guitar Jessica Pierce, Flute Francisco Castillo, Oboe Kevan Torfeh, Cello David McKelvy, Harmonica Anna Bartos, Soprano Executive Album Producers for BSX Records: Ford A. Thaxton and Mark Banning Album Produced by Gregg Nestor Guitar Arrangements by Gregg Nestor Tracks 1-5 and 12-16 Recorded at Penguin Recording, Eagle Rock, CA Engineer: John Strother Tracks 6-11 Recorded at Villa di Fontani, Lake View Terrace, CA Engineers: Jonathan Marcus, Benjamin Maas Digitally Edited and Mastered by Jonathan Marcus, Orpharian Recordings Album Art Direction: Mark Banning Mr. Nestor’s Guitars by Martin Fleeson, 1981 José Ramirez, 1984 & Sérgio Abreu, 1993 Mr. Kanengiser’s Guitar by Miguel Rodriguez, 1977 Special Thanks to the composer’s estates for access to the original scores for this project. BSX Records wishes to thank Gregg Nestor, Jon Burlingame, Mike Joffe and Frank K. DeWald for his invaluable contribution and oversight to the accuracy of the CD booklet. For Ilaine Pollack well-tempered instrument - cannot be tuned for all keys assuredness of its melody foreshadow the seriousness simultaneously, each key change was recorded by the with which this “concert composer” would approach duo sectionally, then combined. Virtuosic glissando and film. pizzicato effects complement Gold's main theme, a jaunty, kaleidoscopic waltz whose suggestion of a Like Korngold, Miklós Rózsa found inspiration in later merry-go-round is purely intentional. years by uniting both sides of his “Double Life” – the title of his autobiography – in a concert work inspired by his The fanfare-like opening of Alfred Newman’s ALL film music. Just as Korngold had incorporated themes ABOUT EVE (1950), adapted from the main title, pulls us from Warner Bros. -

ARSC Journal

LEONARD BERNSTEIN, A COMPOSER DISCOGRAPHY" Compiled by J. F. Weber Sonata for clarinet and piano (1941-42; first performed 4-21-42) David Oppenheim, Leonard Bernstein (recorded 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, 3ss.) Herbert Tichman, Ruth Budnevich (rec. c.1953} Concert Hall Limited Editions H 18 William Willett, James Staples (timing, 9:35) Mark MRS 32638 (released 12-70, Schwann) Stanley Drucker, Leonid Hambro (rec. 4-70) (10:54) Odyssey Y 30492 (rel. 5-71) (7) Anniversaries (for piano) (1942-43) (2,5,7) Leonard Bernstein (o.v.) (rec. 1945) (78: Hargail set MW 501, ls.) (1,2,3) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (4:57) (78: RCA Victor 12 0683 in set DM 1278, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58) (4,5) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (3:32) (78: RCA Victor 12 0228 in set DM 1209, ls.) (vinyl 78: RCA Victor 18 0114 in set DV 15, ls.) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 (6,7) Leonard Bernstein (rec. c.1949) (2:18) Camden CAL 214 (rel. 5-55, del. 2-58); CAL 351 Jeremiah symphony (1941-44; f.p. 1-28-44) Nan Merriman, St. Louis SO--Leonard Bernstein (rec. 12-1-45) ( 23: 30) (78: RCA Victor 11 8971-3 in set DM 1026, 6ss.) Camden CAL 196 (rel. 2-55, del. 6-60) "Single songs from tpe Broadway shows and arrangements for band, piano, etc., are omitted. Thanks to Jane Friedmann, CBS; Peter Dellheim, RCA; Paul de Rueck, Amberson Productions; George Sponhaltz, Capitol; James Smart, Library of Congress; Richard Warren, Jr., Yael Historical Sound Recordings; Derek Lewis, BBC. -

Lister); an American Folk Rhapsody Deutschmeister Kapelle/JULIUS HERRMANN; Band of the Welsh Guards/Cap

Guild GmbH Guild -Light Catalogue Bärenholzstrasse 8, 8537 Nussbaumen, Switzerland Tel: +41 52 742 85 00 - e-mail: [email protected] CD-No. Title Track/Composer Artists GLCD 5101 An Introduction Gateway To The West (Farnon); Going For A Ride (Torch); With A Song In My Heart QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT FARNON; SIDNEY TORCH AND (Rodgers, Hart); Heykens' Serenade (Heykens, arr. Goodwin); Martinique (Warren); HIS ORCHESTRA; ANDRE KOSTELANETZ & HIS ORCHESTRA; RON GOODWIN Skyscraper Fantasy (Phillips); Dance Of The Spanish Onion (Rose); Out Of This & HIS ORCHESTRA; RAY MARTIN & HIS ORCHESTRA; CHARLES WILLIAMS & World - theme from the film (Arlen, Mercer); Paris To Piccadilly (Busby, Hurran); HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; DAVID ROSE & HIS ORCHESTRA; MANTOVANI & Festive Days (Ancliffe); Ha'penny Breeze - theme from the film (Green); Tropical HIS ORCHESTRA; L'ORCHESTRE DEVEREAUX/GEORGES DEVEREAUX; (Gould); Puffin' Billy (White); First Rhapsody (Melachrino); Fantasie Impromptu in C LONDON PROMENADE ORCHESTRA/ WALTER COLLINS; PHILIP GREEN & HIS Sharp Minor (Chopin, arr. Farnon); London Bridge March (Coates); Mock Turtles ORCHESTRA; MORTON GOULD & HIS ORCHESTRA; DANISH STATE RADIO (Morley); To A Wild Rose (MacDowell, arr. Peter Yorke); Plink, Plank, Plunk! ORCHESTRA/HUBERT CLIFFORD; MELACHRINO ORCHESTRA/GEORGE (Anderson); Jamaican Rhumba (Benjamin, arr. Percy Faith); Vision in Velvet MELACHRINO; KINGSWAY SO/CAMARATA; NEW LIGHT SYMPHONY (Duncan); Grand Canyon (van der Linden); Dancing Princess (Hart, Layman, arr. ORCHESTRA/JOSEPH LEWIS; QUEEN'S HALL LIGHT ORCHESTRA/ROBERT Young); Dainty Lady (Peter); Bandstand ('Frescoes' Suite) (Haydn Wood) FARNON; PETER YORKE & HIS CONCERT ORCHESTRA; LEROY ANDERSON & HIS 'POPS' CONCERT ORCHESTRA; PERCY FAITH & HIS ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/JACK LEON; DOLF VAN DER LINDEN & HIS METROPOLE ORCHESTRA; FRANK CHACKSFIELD & HIS ORCHESTRA; REGINALD KING & HIS LIGHT ORCHESTRA; NEW CONCERT ORCHESTRA/SERGE KRISH GLCD 5102 1940's Music In The Air (Lloyd, arr. -

Click to Download

v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c1 Volume 8, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies & Television Action Back In Bond!? pg. 18 MeetTHE Folks GUFFMAN Arrives! WIND Howls! SPINAL’s Tapped! Names Dropped! PLUS The Blue Planet GEORGE FENTON Babes & Brits ED SHEARMUR Celebrity Studded Interviews! The Way It Was Harry Shearer, Michael McKean, MARVIN HAMLISCH Annette O’Toole, Christopher Guest, Eugene Levy, Parker Posey, David L. Lander, Bob Balaban, Rob Reiner, JaneJane Lynch,Lynch, JohnJohn MichaelMichael Higgins,Higgins, 04> Catherine O’Hara, Martin Short, Steve Martin, Tom Hanks, Barbra Streisand, Diane Keaton, Anthony Newley, Woody Allen, Robert Redford, Jamie Lee Curtis, 7225274 93704 Tony Curtis, Janet Leigh, Wolfman Jack, $4.95 U.S. • $5.95 Canada JoeJoe DiMaggio,DiMaggio, OliverOliver North,North, Fawn Hall, Nick Nolte, Nastassja Kinski all mentioned inside! v8n4 covers.qxd 5/13/03 1:58 PM Page c2 On August 19th, all of Hollywood will be reading music. spotting editing composing orchestration contracting dubbing sync licensing music marketing publishing re-scoring prepping clearance music supervising musicians recording studios Summer Film & TV Music Special Issue. August 19, 2003 Music adds emotional resonance to moving pictures. And music creation is a vital part of Hollywood’s economy. Our Summer Film & TV Music Issue is the definitive guide to the music of movies and TV. It’s part 3 of our 4 part series, featuring “Who Scores Primetime,” “Calling Emmy,” upcoming fall films by distributor, director, music credits and much more. It’s the place to advertise your talent, product or service to the people who create the moving pictures. -

A Study of Musical Affect in Howard Shore's Soundtrack to Lord of the Rings

PROJECTING TOLKIEN'S MUSICAL WORLDS: A STUDY OF MUSICAL AFFECT IN HOWARD SHORE'S SOUNDTRACK TO LORD OF THE RINGS Matthew David Young A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF MUSIC IN MUSIC THEORY May 2007 Committee: Per F. Broman, Advisor Nora A. Engebretsen © 2007 Matthew David Young All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Per F. Broman, Advisor In their book Ten Little Title Tunes: Towards a Musicology of the Mass Media, Philip Tagg and Bob Clarida build on Tagg’s previous efforts to define the musical affect of popular music. By breaking down a musical example into minimal units of musical meaning (called musemes), and comparing those units to other musical examples possessing sociomusical connotations, Tagg demonstrated a transfer of musical affect from the music possessing sociomusical connotations to the object of analysis. While Tagg’s studies have focused mostly on television music, this document expands his techniques in an attempt to analyze the musical affect of Howard Shore’s score to Peter Jackson’s film adaptation of The Lord of the Rings Trilogy. This thesis studies the ability of Shore’s film score not only to accompany the events occurring on-screen, but also to provide the audience with cultural and emotional information pertinent to character and story development. After a brief discussion of J.R.R. Tolkien’s description of the cultures, poetry, and music traits of the inhabitants found in Middle-earth, this document dissects the thematic material of Shore’s film score. -

Scarica Programma

Nel moltiplicarsi dei mondi e delle nuove genti risuona dalle antiche profondità di un tempo pur sempre giovane il richiamo del Bello, dell’Intelligenza e dell’Arte. Che è anche comandamento a non vacillare nella loro difesa. Giorgio Ferrara con il patrocinio di Presidenza del Consiglio dei Ministri Ministero degli Affari Esteri e della Cooperazione Internazionale Camera di Commercio di Perugia promosso da official sponsor main supporter official car main partner project sponsor sponsor & supplier premium partner sponsor project partner partner sponsor tecnici main media supporter HOTEL DEI DUCHI SPOLETO Viale G. Matteotti, 4 - 06049 - Spoleto (PG) - Italy Tel. +39 0743 44541 - Fax +39 0743 44543 www.hoteldeiduchi.com - [email protected] DEL GALLO EDITORI D.G.E. srl Z.I. Loc. S. Chiodo | Via dei Tornitori, 7 | 06049 Spoleto-Umbria main media partner Tel. 0743 778383 Fax 0743 778384 | [email protected] con la partecipazione di Ucio culturale Ambasciata di Israele - Roma si ringrazia media partner I MECENATI DEL FESTIVAL DEI 2MONDI ACCADEMIA NAZIONALE DI SANTA CECILIA | CON SPOLETO | CONFCOMMERCIO SPOLETO CONFINDUSTRIA UMBRIA | TRENITALIA SPA | NPS-CONVITTO SPOLETO SISTEMA MUSEO | INTERNATIONAL INNER WHEEL | ROTARY DI SPOLETO PIANOFORTI ANGELO FABBRINI | E.T.C. ITALIA | S.I.C.A.F. SPOLETO PROGRAMMA GIORNALIERO GIUGNO GIUGNO GIUGNO 24 VENERDÌ 25 SABATO 26 DOMENICA 10.00 Palazzo Tordelli 9.30-19.30 Rocca Albornoziana 12.00 / 16.00 9.30-19.30 Rocca Albornoziana p. 259 AMEDEO MODIGLIANI, p. 263 IN-VISIBILE Museo Diocesano Salone dei Vescovi p. 263 IN-VISIBILE LES FEMMES p. 224 GLI INCONTRI inaugurazione 10.00 Cantiere Oberdan DI PAOLO MIELI 10.00-13.00/16.00-20.00 p. -

Dead Zone Back to the Beach I Scored! the 250 Greatest

Volume 10, Number 4 Original Music Soundtracks for Movies and Television FAN MADE MONSTER! Elfman Goes Wonky Exclusive interview on Charlie and Corpse Bride, too! Dead Zone Klimek and Heil meet Romero Back to the Beach John Williams’ Jaws at 30 I Scored! Confessions of a fi rst-time fi lm composer The 250 Greatest AFI’s Film Score Nominees New Feature: Composer’s Corner PLUS: Dozens of CD & DVD Reviews $7.95 U.S. • $8.95 Canada �������������������������������������������� ����������������������� ���������������������� contents ���������������������� �������� ����� ��������� �������� ������ ���� ���������������������������� ������������������������� ��������������� �������������������������������������������������� ����� ��� ��������� ����������� ���� ������������ ������������������������������������������������� ����������������������������������������������� ��������������������� �������������������� ���������������������������������������������� ����������� ����������� ���������� �������� ������������������������������� ���������������������������������� ������������������������������������������ ������������������������������������� ����� ������������������������������������������ ��������������������������������������� ������������������������������� �������������������������� ���������� ���������������������������� ��������������������������������� �������������� ��������������������������������������������� ������������������������� �������������������������������������������� ������������������������������ �������������������������� -

Catalogo IV Fronteirafestival.Pdf

Título: Moça típica da região de Goiás (GO) Acervo: Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE Série: Acervo dos trabalhos geográficos de campo Autor: Desconhecido Local: Goiânia Ano: [195-] Este festival é dedicado a João Henrique Pacheco 21 de março de 1991 † 22 de setembro de 2017 “Não adianta tentar acabar com as minhas ideias, elas já estão pairando no ar. Quando eu parar de sonhar, eu sonharei pela cabeça de vocês. Não pararei porque não sou mais um ser humano, eu sou uma ideia. A morte de um combatente não para uma revolução”. Luís Inácio Lula da Silva São Bernardo do Campo - 7 de abril de 2018 SUMÁRIO: 15 APRESENTAÇÃO 17 RADICALIDADE E RISCO | Camilla Margarida 23 E NÓS? | Camilla Margarida, Henrique Borela, Marcela Borela e Rafael Parrode 29 SESSÃO DE ABERTURA 35 UM INCÔMODO FESTIM SOBRE O OLHAR | Lúcia Monteiro e Patrícia Mourão 43 COMPETITIVA INTERNACIONAL DE LONGAS-METRAGENS 47 TIERRA SOLA E AS HISTÓRIAS DA ILHA DE PÁSCOA | Marcelo Ribeiro 53 EUFORIA | Dalila Camargo Martins 61 O TRAUMA DA HISTÓRIA E O CONTRAFOGO DO CINEMA | Marcelo Ribeiro 67 NENHUMA LUZ NO FIM DO TÚNEL | Rafael Parrode 75 OS MIL OLHOS DA LIBÉLULA | Rafael Parrode 85 QUEM SOU EU, PRA ONDE VOU, DE ONDE VIM? | Ricardo Roqueto 91 A TERRA É INAVEGÁVEL | Dalila Camargo Martins 97 OUROBOROS E O HORIZONTE DA BARBÁRIE| Marcelo Ribeiro 101 COMPETITIVA INTERNACIONAL DE CURTAS-METRAGENS 103 ESTADOS DE EMERGÊNCIA | Rafael Parrode 115 O MUNDO QUE FALTA | Camilla Margarida 131 PAISAGENS DA MEMÓRIA | Ricardo Roqueto 143 ATUALIDADE ROSSELLINI 145 APRESENTAÇÃO -

If the Stones Were the Bohemian Bad Boys of the British R&B Scene, The

anEHEl s If the Stones were the bohemian bad boys of the British R&B scene, the Animals were its working-class heroes. rom the somber opening chords of the than many of his English R&B contemporaries. The Animals’ first big hit “House of the Rising Animals’ best records had such great resonance because Sun,” the world could tell that this band Burdon drew not only on his enthusiasm, respect and was up to something different than their empathy for the blues and the people who created it, but British Invasion peers. When the record also on his own English working class sensibilities. hitP #1 in England and America in the summer and fall of If the Stones were the decadent, bohemian bad boys 1964, the Beatles and their Mersey-beat fellow travellers of the British R&B scene, the Animals were its working- dominated the charts with songs like “I Want to Hold Your class heroes. “We Gotta Get Out of This Place” and “It’s My Hand” and “Glad All Over.” “House of the Rising Sun,” a tra Life,” two Brill Building-penned hits for the band, were ditional folk song then recently recorded by Bob Dylan on informed as much by working-class anger as by Burdons his debut album, was a tale of the hard life of prostitution, blues influences, and the bands anthemic background poverty and despair in New Orleans. In the Animals’ vocals underscored the point. recording it became a full-scale rock & roll drama, During the two-year period that the original scored by keyboardist Alan Price’s rumbling organ play Animals recorded together, their electrified reworkings of ing and narrated by Eric Burdons vocals, which, as on folk songs undoubtedly influenced the rise of folk-rock, many of the Animals’ best records, built from a foreboding and Burdons gritty vocals inspired a crop of British and bluesy lament to a frenetic howl of pain and protest.