How ' E Sopranos' Realistically Portrays Alzheimer's Disease

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Sopranos Episode Guide Imdb

The sopranos episode guide imdb Continue Season: 1 2 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 2002 2004 2006 2007 Season: 1 2 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 200102 200204 2006 2007 Season: 1 2 3 3 4 5 6 OR Year: 1999 2000 2001 2002 2004 2006 2007 Edit It's time for the annual ecclera and, as usual, Pauley is responsible for the 5 day affair. It's always been a money maker for Pauley - Tony's father, Johnny Soprano, had control over him before him - but a new parish priest believes that the $10,000 Poly contributes as the church's share is too low and believes $50,000 would be more appropriate. Pauley shies away from that figure, at least in part, he says, because his own spending is rising. One thing he does to save money to hire a second course of carnival rides, something that comes back to haunt him when one of the rides breaks down and people get injured. Pauley is also under a lot of stress after his doctor dislikes the results of his PSA test and is planning a biopsy. When Christopher's girlfriend Kelly tells him he is pregnant, he asks her to marry him. He is still struggling with his addiction however and falls off the wagon. Written by GaryKmkd Plot Summary: Add a Summary Certificate: See All The Certificates of the Parents' Guide: Add Content Advisory for Parents Edit Vic Noto plays one of the bikies from the Vipers group that Tony and Chris steal wine from. -

Sagawkit Acceptancespeechtran

Screen Actors Guild Awards Acceptance Speech Transcripts TABLE OF CONTENTS INAUGURAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...........................................................................................2 2ND ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .........................................................................................6 3RD ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ...................................................................................... 11 4TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 15 5TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 20 6TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 24 7TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 28 8TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 32 9TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ....................................................................................... 36 10TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 42 11TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS ..................................................................................... 48 12TH ANNUAL SCREEN ACTORS GUILD AWARDS .................................................................................... -

A Midsummer Nights Dream 11 'T} S , O(;;)-2 by Wilham Shakespeare

A Midsummer NightS Dream 11 't} s , o(;;)-2 by WilHam Shakespeare ~ BAm~ Tiieater BRooKLYN AcADEMY oF Music Compa11y ~~~~~~~~~ \.. ~ , •' II I II Q ,\.~ I II 1 \ } ( "' '" \ . • • !I II'" r )DO I \ ., : \ I ~\ } .. \ ;; .; 'I' ... .. _:..,... 1t ; rJ ,.I •\ y v \ YOUR MONEY GROWS LIKE MAGIC AT THE THE DIME SAVINGS BANK DF NEW YORK -..1-..ett•O•C MANHATTAN • DOWNTOWN BROOKLYN • BENSONHURST • FLATBUSH CONEY ISLAND • KINGS PLAZA • VALLEY STREAM • MASSAPEQUA HUNTINGTON STATION TABLE OF Old CONTENTS Hungary "An authentic ~ ounpany~~~~~~~ Hungarian restaurant right here in Brooklyn" Beef Goulash, Ch1cken Papnka, St uffed Cabbage, Palacsinta and other traditional dishes " Live Piano Music Nightly" The Actors 5-8 PRE-T HEATRE AND AFTER THEATRE DINNER 142 Montague St., Bklyn . Hghts. Notes on the Play 9-14 625· 1649 Production Team 15 § The Staff 16 'R(!tauranb The Actors 17-19 tel: 855-4830 Contributors 20-21 UL8-2000 Board of Directors 22 open daily for lunch and dinner till 9 P. M. Italian and A m erican Cuisine special orders upon request Flowers, plants and fruit baskets for all occasions (212) 768-6770 25th Street & 768-0800 5th Avenue Deluxe coach service following DIRECTORY BAM Theater Company Directory of Facilities a nd Services Box Office: Monday 10 00 to &.00 Tue.day throu~h ~tur performances day 10 00 to Y 00 Sunday Performance limes only Lost ond ~o und : Telephone &36-4 150 Restroom: Operu We pick you up and take you back llouse Women .ond Men. Mezzanme level. HandKapp<.·d Or c h c~t r a level Ployh ou,e: Women Orchestra l~vcl ,\.1cn .'Ae1 (to Manhattan) 1.anme lt•vel llandocapped Orchestra level Lepercq Spucc: The BAMBus Express will pick-up BAM Theater Company Wom en ,,nd Men Tht•c.H e r level Public T ele phon es. -

The Evening Will Kick-Off with an Exclusive Performance by Dominic

The evening will kick-off with an exclusive performance by Dominic Chianese, Emmy-Nominated actor, singer and musician best known for his role as Junior on The Sopranos. The concert, which will benefit the 175th Anniversary Annual Fund and the Prep’s Fine Arts Programs, will be held on Saturday, March 11, 2017 in the Leonard Theatre. Ronan Tynan has performed for Presidents and Popes and at major concert halls, sports venues and historic locations around the world. His versatile range of repertoire includes the operatic, oratorio, concert and popular music genres. His song selection for the concert at Fordham Prep will highlight music stretching back over the Prep’s 175-year history. Here is an example of his amazing talent. Three levels of tickets will be offered – Orchestra at EACH TICKET INCLUDES: $175, Mezzanine at $125 and Balcony at $75. • A cocktail party with passed hors d’oeuvres, For those not familiar with the Leonard Theatre, crudités, beer, wine and soda plus socializing with please click here to see the diagram. members of the Prep community; The Prep is soliciting Sponsors & Event Underwriters • Coffee, pastries and beer, wine and soda after who will be featured prominently in four special ways: the concert; highlighted on our webpage through June, 2017, in the Event Program distributed at the concert, • Free parking and shuttle service from the University in our Summer 2017 Ramview and in the 2017 parking garage. Annual Report. Plus, Sponsors will be invited to a If you have any questions about tickets or Sponsor/ cocktail reception with Fr. Devron in the spring. -

The Museum of Modern Art Presents a Discussion of the HBO Series the Sopranos with the Series Writer/Director David Chase and No

MoMA | press | Releases | 2001 | Discussion on The Sopranos Page 1 of 3 For Immediate Release February 2001 THE MUSEUM OF MODERN ART HOSTS DISCUSSION ON THE SOPRANOS Discussion with David Chase and media writer Ken Auletta February 12, 2001 The Sopranos February 3-13, 2001 The Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1 The Museum of Modern Art presents a discussion of the HBO series The Sopranos with the series writer/director David Chase and noted media writer and author Ken Auletta, February 12, 2001 at 6:00 p.m. at the Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1. Recording the domestic dramas and business anxieties of family living the bourgeois life in a pleasant New Jersey suburb, The Sopranos is a saga of middle-class life in America at the turn of the century. Chronicled in twenty-six hour-long episodes, the first two seasons from the series will be shown in two four-day sequences at The Museum of Modern Art, from February 3-13 at the Roy and Niuta Titus Theatre 1. "The Sopranos is a cynical yet deeply felt look at this particular family man," remarks Laurence Kardish, Senior Curator, Department of Film and Video, who organized the program. "David Chase and his team have created a series distinguished by its bone-dry humor and understated, quirky, and stinging perspective - not usually seen on television." Renowned for his savvy profiles of power players in the media, Ken Auletta will join David Chase for a discussion of The Sopranos at The Museum on February 12. The Department of Film and Video gratefully acknowledges HBO for making the series available for public viewing. -

CONGRESSIONAL RECORD— Extensions of Remarks E1641 HON

September 15, 2010 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1641 mud on them yet. We lost a lot of men PERSONAL EXPLANATION IN HONOR OF FIRE CHIEF there.’’ TIMOTHY A. POTTS ‘‘Then as soon as the war ended in Oki- HON. JOSEPH CROWLEY nawa, they loaded us on LST’s and they took OF NEW YORK HON. DENNIS J. KUCINICH us to Korea. We went in on the west side at OF OHIO a place called Inchon. They loaded us on a IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES narrow-gage railway train, and every little Wednesday, September 15, 2010 hill that we’d go up, we’d have to get out and Wednesday, September 15, 2010 Mr. CROWLEY. Madam Speaker, on Sep- help push the train,’’ Harrison said. tember 14, 2010 I was absent for two rollcall Mr. KUCINICH. Madam Speaker, I rise His unit, now the 42nd Engineering Con- votes. If I had been here, I would have voted: today in honor of Fire Chief Timothy A. Potts struction Battalion, was deployed near ‘‘yea’’ on rollcall vote 519 and ‘‘yea’’ on rollcall on the occasion of his retirement from the Seoul, Korea, in late August, 1945, to help vote 520. Olmsted Falls Fire Department. He honorably build the Temple Airfield. served the people of Olmsted Falls with un- ‘‘I remember the first time I went up the f wavering dedication for 35 years as a para- streets of Seoul, you could go across the Han PERSONAL EXPLANATION medic, firefighter and fire chief. river and look straight ahead to the capitol Chief Potts joined the Olmsted Falls Fire and it looked like a beautiful city, and from Department on April 14, 1975, and two years the front side of the street it did, but you’d HON. -

Intersection of Gender and Italian/Americaness

THE INTERSECTION OF GENDER AND ITALIAN/AMERICANESS: HEGEMONY IN THE SOPRANOS by Niki Caputo Wilson A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of The Dorothy F. Schmidt College of Arts and Letters in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Florida Atlantic University Boca Raton, FL December 2010 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have completed this dissertation without the guidance of my committee members, the help from my friends and colleagues, and the support of my family. I extend my deepest gratitude to my committee chair Dr. Jane Caputi for her patience, guidance, and encouragement. You are truly an inspiration. I would like to thank my committee members as well. Dr. Christine Scodari has been tireless in her willingness to read and comment on my writing, each time providing me with insightful recommendations. I am indebted to Dr Art Evans, whose vast knowledge of both The Sopranos and ethnicity provided an invaluable resource. Friends, family members, and UCEW staff have provided much needed motivation, as well as critiques of my work; in particular, I thank Marc Fedderman, Rebecca Kuhn, my Aunt Nancy Mitchell, and my mom, Janie Caputo. I want to thank my dad, Randy Caputo, and brother, Sean Caputo, who are always there to offer their help and support. My tennis friends Kathy Fernandes, Lise Orr, Rachel Kuncman, and Nicola Snoep were instrumental in giving me an escape from my writing. Mike Orr of Minuteman Press and Stefanie Gapinski of WriteRight helped me immensely—thank you! Above all, I thank my husband, Mike Wilson, and my children, Madi and Cole Wilson, who have provided me with unconditional love and support throughout this process. -

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative

Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative Carmela Coccimiglio Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate and Postdoctoral Studies in partial fulfilment of the requirements for a doctoral degree in English Literature Department of English Faculty of Arts University of Ottawa © Carmela Coccimiglio, Ottawa, Canada, 2013 TABLE OF CONTENTS Abstract iii Acknowledgements v Introduction 1 Chapter One 27 “Senza Mamma”: Mothers, Stereotypes, and Self-Empowerment Chapter Two 57 “Three Corners Road”: Molls and Triangular Relationship Structures Chapter Three 90 “[M]arriage and our thing don’t jive”: Wives and the Precarious Balance of the Marital Union Chapter Four 126 “[Y]ou have to fucking deal with me”: Female Gangsters and Textual Outcomes Chapter Five 159 “I’m a bitch with a gun”: African-American Female Gangsters and the Intersection of Race, Sexual Orientation, and Gender Conclusion 186 Works Cited 193 iii ABSTRACT Absent Presence: Women in American Gangster Narrative investigates women characters in American gangster narratives through the principal roles accorded to them. It argues that women in these texts function as an “absent presence,” by which I mean that they are a convention of the patriarchal gangster landscape and often with little import while at the same time they cultivate resistant strategies from within this backgrounded positioning. Whereas previous scholarly work on gangster texts has identified how women are characterized as stereotypes, this dissertation argues that women characters frequently employ the marginal positions to which they are relegated for empowering effect. This dissertation begins by surveying existing gangster scholarship. There is a preoccupation with male characters in this work, as is the case in most gangster texts themselves. -

Crossings a Newsletter of the Foundation for Alzheimer's and Cultural Memory

Memory Bridge Newsletter Page 1 of 9 Crossings A Newsletter of the Foundation for Alzheimer's and Cultural Memory June 10, 2008 Hello from Memory Bridge I hope this edition of Crossings finds you in good spirits, deeply connected with friends and loved ones. Last year Memory Bridge launched our new Memory Bridge website (www.memorybridge.org), began to disseminate our Memory Bridge school program across the United States, and debuted our PBS documentary There Is a Bridge . We have received overwhelmingly supportive feedback about There Is a Bridge from around the world. Here is a sample of what folks are saying: "I watched the clip with Mrs. Wilson and I saw Love in action. I cried. This was so beautiful, like something lifted out of time and space; proving that connectedness, regardless of outward differences or appearances, is the truth of us all. We are one." Trudy · Santa Cruz, California "Last night, Monday the 8th of October, I saw your program and it absolutely renewed my faith in compassion for people. The only time I had seen this was in the 80s and 90s during the AIDS devastation. Unfortunately it rarely exists anymore. But you certainly hit my heart and mind last night. Thank you." Maurice Pacini · Los Angeles, California "I watched the film last night. I thought it was fabulous! I teach nursing and am currently in a long term care facility with my students. I would love to make this a required viewing opportunity for them." Laura Herbert · Ohio "Amazing!" A Young Person · Central California If you have not seen There Is a Bridge and would like to know why the documentary is touching so many people in such a poignant way, you can see it when it airs on the PBS station in your area, or you can order a DVD of There Is a Bridge at www.memorybridge.org . -

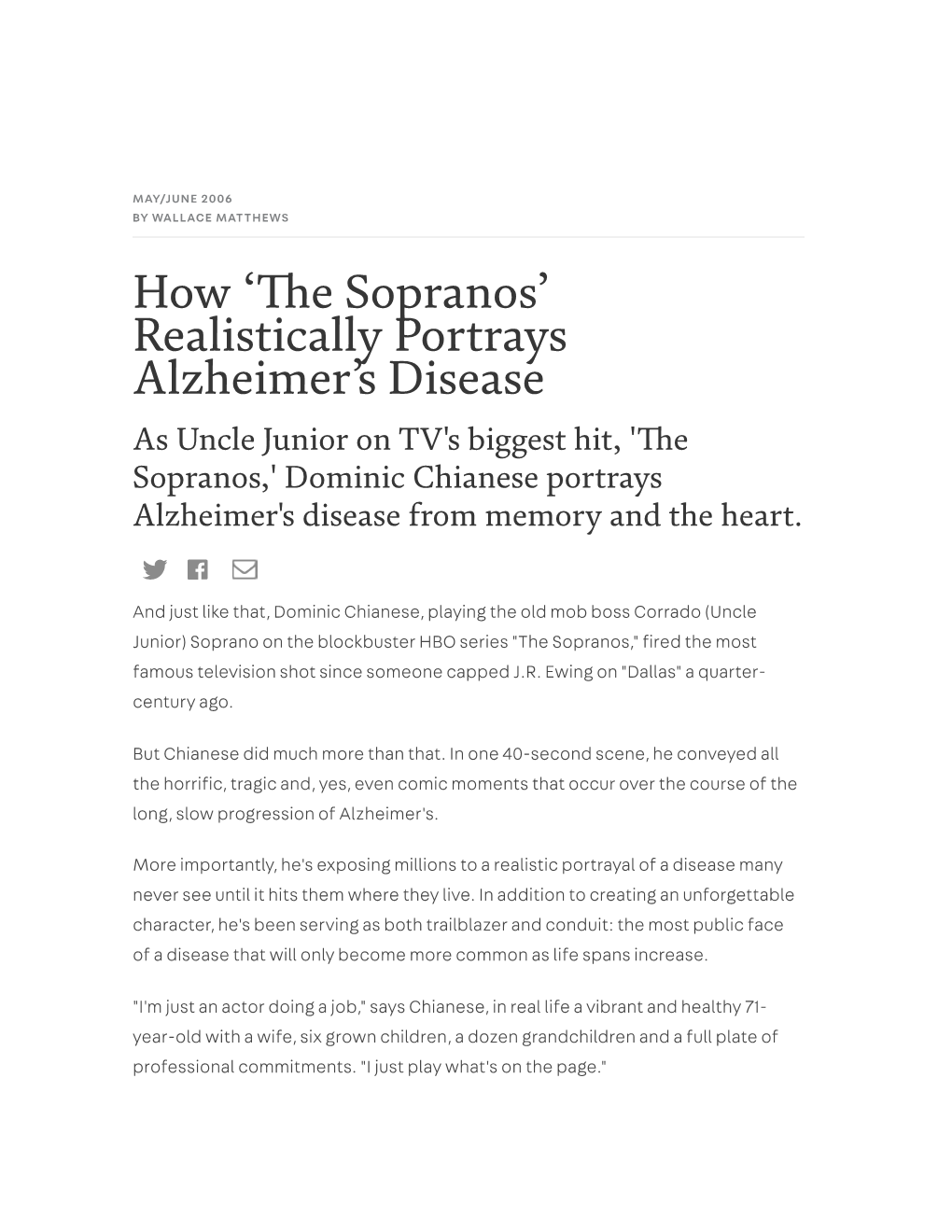

How ' E Sopranos' Realistically Portrays Alzheimer's Disease

MAY/JUNE 2006 BY WALLACE MATTHEWS How ‘~e Sopranos’ Realistically Portrays Alzheimer’s Disease As Uncle Junior on TV's biggest hit, '~e Sopranos,' Dominic Chianese portrays Alzheimer's disease from memory and the heart. And just like that, Dominic Chianese, playing the old mob boss Corrado (Uncle Junior) Soprano on the blockbuster HBO series "The Sopranos," fired the most famous television shot since someone capped J.R. Ewing on "Dallas" a quarter- century ago. But Chianese did much more than that. In one 40-second scene, he conveyed all the horrific, tragic and, yes, even comic moments that occur over the course of the long, slow progression of Alzheimer's. More importantly, he's exposing millions to a realistic portrayal of a disease many never see until it hits them where they live. In addition to creating an unforgettable character, he's been serving as both trailblazer and conduit: the most public face of a disease that will only become more common as life spans increase. "I'm just an actor doing a job," says Chianese, in real life a vibrant and healthy 71- year-old with a wife, six grown children, a dozen grandchildren and a full plate of professional commitments. "I just play what's on the page." Dominic Chianese is also playing what's in his heart and in his memory. His knowledge of dementia and his empathy for Alzheimer's patients come firsthand. For more than 20 years, he has volunteered as a recreational worker at St. Cabrini Nursing Home in Dobbs Ferry, N.Y., singing and playing guitar for its 300 residents, more than half of whom have Alzheimer's. -

Commendatori

Commendatori "Commendatori" is the seventeenth episode of the HBO original series The Sopranos and the fourth of the show's second season. It was written by David Chase and directed by Tim Van Patten, and originally aired on February 6, 2000. James Gandolfini as Tony Soprano. Lorraine Bracco as Dr. Jennifer Melfi *. Edie Falco as Carmela Soprano. Michael Imperioli as Christopher Moltisanti. Dominic Chianese as Corrado Soprano, Jr. Vincent Pastore as Pussy Bonpensiero. Steven Van Zandt as Silvio Dante. Commendatore ┠Det italienske ord commendatore betegner oprindelig en standsperson som forvalter en ridderordens jordegods. Senere er ordet gået over til at være en ren ærestitel. Titlen svarer til tysk Komthur. Den nærmeste danske oversættelse er kommandør . I ⦠Danske encyklopædi. English examples for "Commendatore" - She was the recipient of many major awards including Commendatore of the Italian Republic. He was named Commendatore of the Order of the Crown of Italy. "How the devil can I guess who she is?" said the Commendatore. Commander (Italian: Commendatore, French: Commandeur, German: Komtur, Spanish: Comandante, Portuguese: Comendador), or Knight Commander, is a title of honor prevalent in chivalric order and fraternal orders. The title of Commander occurred in the medieval military orders, such as the Knights Hospitaller, for a member senior to a Knight. Variations include Knight Commander, notably in English, sometimes used to denote an even higher rank than Commander. In some orders of chivalry, Commander ranks above Commendatore definition is - a member of an Italian honorary order of chivalry who ranks next above an officer and next below a grand officer. : a member of an Italian honorary order of chivalry who ranks next above an officer and next below a grand officer. -

THE Minority Decision Causes Diverse Reactions

THE O b s e r v e r The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Marys VOLUME 40 : ISSUE 117 WEDNESDAY, APRIL 5, 2006 NDSMCOBSERVER.COM Minority decision causes diverse reactions Last week's Student Senate vote against making ad-hoc MAC a recognized part of student government angers, prompts action “The number one issue is Boyd said she was angered The committee was formed in MAC chair Destinee DeLemos By KAREN LANGLEY that MAC represents 20 per by the amendment’s defeat — a April 2005 with the goal of giv met to compose the amend Associate News Editor cent of the student body,” said vote she said she had not ing a voice in student govern ment, which would have estab Rhea Boyd, who chaired MAC expected. ment to racially underrepre lished the committee perma The Student Senate’s defeat this past year. “To have that But the issue will soon resur sented groups. Before that nently as a “means of expres last Wednesday of an amend h u g e of a face. Student body president time, issues of race had been sion for racially and ethnically ment to make the ad-hoc constituency Lizzi Shappell said Friday she addressed by the permanent marginalized students.” Minority Affairs committee w ith o u t a expects a new resolution to be Senate Diversity committee. Last Tuesday — the night (MAC) a constitutionally-recpg- voice in stu ready within a few weeks after That committee now under before the Senate meeting — nized part of student govern dent govern review by a newly established takes issues related to religious Baron, Shappell and Liu met ment has angered some stu ment is un task force.