Vulpes Macrotis, Kit

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes Macrotis)

Author's Personal Copy J. Comp. Path. 2019, Vol. 167, 60e72 Available online at www.sciencedirect.com ScienceDirect www.elsevier.com/locate/jcpa DISEASE IN WILDLIFE OR EXOTIC SPECIES Dental and Temporomandibular Joint Pathology of the Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis) N. Yanagisawa*, R. E. Wilson*, P. H. Kass† and F. J. M. Verstraete* *Department of Surgical and Radiological Sciences and † Department of Population Health and Reproduction, School of Veterinary Medicine, University of California, Davis, California, USA Summary Skull specimens from 836 kit foxes (Vulpes macrotis) were examined macroscopically according to predefined criteria; 559 specimens were included in this study. The study group consisted of 248 (44.4%) females, 267 (47.8%) males and 44 (7.9%) specimens of unknown sex; 128 (22.9%) skulls were from young adults and 431 (77.1%) were from adults. Of the 23,478 possible teeth, 21,883 teeth (93.2%) were present for examina- tion, 45 (1.9%) were absent congenitally, 405 (1.7%) were acquired losses and 1,145 (4.9%) were missing ar- tefactually. No persistent deciduous teeth were observed. Eight (0.04%) supernumerary teeth were found in seven (1.3%) specimens and 13 (0.06%) teeth from 12 (2.1%) specimens were malformed. Root number vari- ation was present in 20.3% (403/1,984) of the present maxillary and mandibular first premolar teeth. Eleven (2.0%) foxes had lesions consistent with enamel hypoplasia and 77 (13.8%) had fenestrations in the maxillary alveolar bone. Periodontitis and attrition/abrasion affected the majority of foxes (71.6% and 90.5%, respec- tively). -

San Joaquin Kit Fox Habitat Use in Urban Bakersfield

SAN JOAQUIN KIT FOX HOME RANGE, HABITAT USE, AND MOVEMENTS IN URBAN BAKERSFIELD by Nancy Frost A Thesis Presented to The Faculty of Humboldt State University In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Science In Natural Resources: Wildlife December 2005 ABSTRACT San Joaquin kit fox home range, habitat use, and movements in urban Bakersfield Nancy Frost Habitat destruction and fragmentation has led to the decline of the federally endangered and state threatened San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotis mutica). Kit foxes in the San Joaquin Valley occur in and adjacent to several urban areas. The urban kit fox population in Bakersfield has the potential to contribute to recovery efforts, however, little is known about habitat use in the urban environment. Habitat use in the urban landscape was examined in 28 radiocollared adult kit foxes between 1 May 1997 and 15 January 1998. The area of the urban environment needed to meet kit foxes’ ecological requirements varied among the sexes and fluctuated throughout the year. Mean home range size was 1.72 km2 (100% minimum convex polygon estimate) and mean concentrated use area (core area; 50% fixed kernel estimate) size was 0.16 km2. Females had a greater median number of core areas than did males, but core area size did not differ between the sexes. Mean home range size was significantly larger during the dispersal season than during the pair formation and breeding seasons. Home range size was greater for males than females during the breeding season. To assess the extent to which kit foxes were concentrated around limited resources, the percentage of overlap between adjacent kit foxes’ home ranges and core areas was determined. -

Reintroducing San Joaquin Kit Fox to Vacant Or Restored Lands: Identifying Optimal Source Populations and Candidate Foxes

REINTRODUCING SAN JOAQUIN KIT FOX TO VACANT OR RESTORED LANDS: IDENTIFYING OPTIMAL SOURCE POPULATIONS AND CANDIDATE FOXES PREPARED FOR THE U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT CONSERVATION PROGRAM 2800 COTTAGE WAY, SACRAMENTO, CA 95825 Prepared by: Samantha Bremner-Harrison1 & Brian L. Cypher California State University, Stanislaus Endangered Species Recovery Program P.O. Box 9622 Bakersfield, CA 93389 1Current address: School of Animal, Rural and Environmental Sciences Nottingham Trent University, Brackenhurst Campus Southwell NG25 0QF 2011 Kit fox relocation report_ESRP.doc REINTRODUCING SAN JOAQUIN KIT FOX TO VACANT OR RESTORED LANDS: IDENTIFYING OPTIMAL SOURCE POPULATIONS AND CANDIDATE FOXES TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ............................................................................................................... i Introduction ....................................................................................................................... 6 Behavioral variation and suitability ........................................................................................................... 6 Objectives .................................................................................................................................................. 8 Methods .............................................................................................................................. 9 Study sites ................................................................................................................................................. -

San Joaquin Kit Fox (Vulpes Macrotus Mutica)

Mammals San Joaquin Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotus mutica) San Joaquin Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotus mutica) Status State: Threatened Federal: Endangered Population Trend Global: Declining State: Declining Within Inventory Area: Unknown Data Characterization The location database for the San Joaquin kit fox (Vulpes macrotus mutica) within its known range in California includes 22 data records from 1975 to 1999. Of these records, none of the 7 documented within the past 10 years were of sufficient precision to be accurately located within the survey areas. Three of these 7 records are located within the ECCC HCP/NCCP inventory area. These records represent sighting within non-native grassland, grazed, and agricultural habitat. This database includes records of individual sightings and locations of occupied, vacant, and natal dens. A moderate amount of literature is available for the San Joaquin kit fox because of its endangered status. Long-term studies have been conducted on the ecology and population dynamics of this species in core population centers at the Elk Hills and Buena Vista Naval Petroleum Reserves in Kern County and on the Carrizo Plain Natural Area in San Luis Obispo County. Numerous surveys have been conducted in the northern portion of the range, including Contra Costa County. Quantitative data are available on population size, reproductive capacity, mortality, dispersal, home-range movement patterns, and habitat characteristics and requirements. A number of models have been developed to describe the species’ population dynamics. A recovery plan for the San Joaquin kit fox has been published. Range The San Joaquin kit fox is found only in the Central Valley area of California. -

World Wildlife Fund Swift Fox Report

SWIFT FOX CONSERVATION TEAM Swift Fox in Valley County, Montana. Photo courtesy of Ryan Rauscher REPORT FOR 2009-2010 SWIFT FOX CONSERVATION TEAM: REPORT FOR 2009-2010 COMPILED AND EDITED BY: Kristy Bly World Wildlife Fund May 2011 Preferred Citation: Bly, K., editor. 2011. Swift Fox Conservation Team: Report for 2009-2010. World Wildlife Fund, Bozeman, Montana and Montana Department of Fish, Wildlife and Parks, Helena 2 TABLE OF CONTENTS Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 5 Swift Fox Conservation Team Members ............................................................................................. 6 Swift Fox Conservation Team Participating Cooperators .................................................................... 7 Swift Fox Conservation Team Interested Parties ................................................................................. 8 STATE AGENCIES Colorado Status of Swift Fox Activities in Colorado, 2009-2010 Jerry Apker ............................................................................................................................. 10 Kansas Swift Fox Investigations in Kansas, 2009-2010 Matt Peek ................................................................................................................................ 11 Montana Montana 2009 and 2010 Swift Fox Report Brian Giddings ...................................................................................................................... -

Influence of Water Temperature and Beaver Ponds on Lahontan Cutthroat Trout in a High-Desert Stream, Southeastern Oregon

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF Andrew G. Talabere for the degree of Master of Science in Fisheries Science presented on November 21. 2002. Title: Influence of Water Temperature and Beaver Ponds on Lahontan Cutthroat Trout in a High-Desert Stream, Southeastern Oregon Abstract approved Redacted for Privacy Redacted for Privacy The distribution of Lahontan cutthroat trout Oncorhynchus clarki henshawi was assessed in a high-desert stream in southeastern Oregon where beaver Castor canadensis are abundant. Longitudinal patterns of beaver ponds, habitat, temperature, and Lahontan cutthroat trout age group distribution were identified throughout Willow Creek. Three distinct stream segments were classified based on geomorphological characteristics. Four beaver-pond and four free-flowing sample sections were randomly located in each of the three stream segments. Beavers substantially altered the physical habitat of Willow Creek increasing the depth and width of available habitat. In contrast, there was no measurable effect on water temperature. The total number of Lahontan cutthroat trout per meter was significantly higher in beaver ponds than free-flowing sections. Although density (fish! m2) showed no statistically significant (P < 0.05) increase, values in beaver pondswere two-fold those of free-flowing sections. Age- 1 and young-of-the-year trout were absent or in very low numbers in lower Willow Creek because of elevated temperatures, but high numbers of age-2 and 3 (adults) Lahontan cutthroat trout were found in beaver ponds where water temperatures reached lethal levels (>24°C). Apparently survival is greater in beaver ponds than free-flowing sections as temperatures approach lethal limits. Influence of Water Temperature and Beaver Ponds on Lahontan Cutthroat Trout in a High- Desert Stream, Southeastern Oregon by Andrew G. -

Plant Communities of the Steens Mountain Subalpine Grassland and Their Relationship to Certain En

AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF John William Mairs for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Geography presented on April 29, 1977 Title: PLANT COMMUNITIES OF THE STEENS MOUNTAIN SUBALPINE GRASSLAND AND THEIR RELATIONSHIP TO CERTAIN EN- VIRONMENTAL ELEMENTS Abstract approved: Redacted for Privacy Robert E. Frenkel Plant communities in a 3.5 km2area along the summit ridge of Steens Mountain, Harney County in southeastern Oregon are identified. The character of winter snow deposi- tion and spring melt in this subalpine zone is a major fac- tor in producing the vegetation pattern.Past domestic grazing, topography, wind pattern, climate, soil depth and soil moisture availability are related to the present vege- tation mosaic. Computer-assisted vegetation ordination of 278 tran- sect-located sample units using SIMORD and tabular plant association analysis of 346 areally-located releves using PHYTO were applied complementarily. Aided by the interpre- tation of true-color aerial photography (1:5000), this analysis revealed and mapped 12 plant communities and one additional combination community named after dominant species. After comparison of four selected similarity indexes commonly used in vegetation ordination analysis, Sorensen's modified similarity index was chosen as best for interpretation of stand groupings in the study data. The general vernal snow cover recession pattern was verified with LANDSAT-1 digital data representations. Plant communities associated with snow deflation, or crest, areas are Erigeron compositus-Astragalus whitneyi, -

KIT FOX Vulpes Macrotis

A-28 KIT FOX Vulpes macrotis Description The small-bodied kit fox closely resembles the swift fox (Vulpes velox) but has larger ears and a more angular appearance. The skull is long and delicate, and The kit fox is the broader at the eyes and more slender at the nose than other North American daintiest of three Vulpes. The ears are set close to the midline of the skull (McGrew 1979, species of Vulpes in Sheldon 1992). The kit fox measures 730 to 840 mm in total length; including a North America 260 to 323 mm tail, 78 to 94 mm ears, and 113 to 137 mm hindfeet. Adult (Fitzgerald et al. weight ranges from 1.5 to 2.5 kg. Females are 15 percent lighter on average 1994). than males (Fitzgerald et al. 1994), but there is no other obvious sexual dimorphism. Tail length averages about 40 percent of total body length—a distinguishing trait, along with the large ears, from swift foxes (Sheldon 1992). The kit fox has a light-colored pelage, variable between grizzled-gray, yellow- gray and buff-gray. The shoulders, flanks and chest range from buff to orange. Guard hairs are tipped black or banded. The underfur is lighter buff or white, and relatively heavy and coarse. The legs are slender and thickly furred. The sides of the muzzle are blackish or brownish, and the tip of the tail is black. The soles of the feet are protected by stiff tufts of hair. Because of its relative coarseness, a kit fox pelt has little market value (O'Farrell 1987). -

Feasibility and Strategies for Translocating San Joaquin Kit Foxes to Vacant Or Restored Habitats

FEASIBILITY AND STRATEGIES FOR TRANSLOCATING SAN JOAQUIN KIT FOXES TO VACANT OR RESTORED HABITATS PREPARED FOR THE CENTRAL VALLEY PROJECT CONSERVATION PROGRAM U.S. BUREAU OF RECLAMATION AND U.S. FISH AND WILDLIFE SERVICE SACRAMENTO, CA 95825 Prepared by: Samantha Bremner-Harrison and Brian L. Cypher California State University, Stanislaus Endangered Species Recovery Program 1900 N. Gateway #101 Fresno, CA 93727 November 2007 FEASIBILITY AND STRATEGIES FOR REINTRODUCING SAN JOAQUIN KIT FOXES TO VACANT OR RESTORED HABITATS Samantha Bremner-Harrison and Brian L. Cypher California State University, Stanislaus Endangered Species Recovery Program TABLE OF CONTENTS Table of Contents ...............................................................................................................i 1. Introduction................................................................................................................... 1 2. Literature review of animal reintroductions and translocations ............................. 2 2.1. Introduction and definitions ............................................................................................. 2 2.2. Common issues associated with reintroduction programs............................................. 3 2.2.1. Expense....................................................................................................................................... 3 2.2.2. Available habitat ........................................................................................................................ -

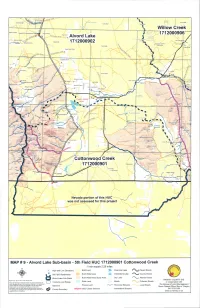

Alvord Lake Toerswnq Ihitk-Ul,.N Itj:Lnir

RtflOP' nt T37S Rt3F T37SR36E T37S R3275E 137S R34E TITStSE BloW Pour Willow Creek Babes Canyor Relds BIM Adrnirtistrative SiteFjel NeSs Airstrip / 41 171 2000906 Alvord Lake tOerswnq ihiTk-ul,.n itj:Lnir. Inokoul hluutte\ McDade Ranch 1712000902 I cvwr Twin Hot Spn Os Wilhlants Canyon , ,AEyy.4N seiralNo WARM APRI '738SR37E rIBS R3BE R38E Lower Roux Place err hlomo * / Oaterkirk Rartch - S., Rabbit HOe Mine 7,g.hit 0 Ptace '0 Arstnp 0 0 Ainord Vafley Lavy1ronrb P -o Rriaia .....c I herbbrrr RarrCh C _: 9S R34E Trout Creek CAhn '5- T39S R36E N Oleacireen Place T395 R37F Cruallu Canyon -1 Oleachea Pass T39S R38E \ Stergett Cabot Trout Creek Ranch ty Silvey Adrian Place' Wee Pole Canyon C SPRiNG, WHITEHORSE RANCH LN Pueblo Valley 4040 S Center Ridg Will, reek Pt cLean Cabin orgejadowo Gob 0810 WEIi Reynolds Ranch Owens Randr / I p labor Mocntai /1 °ueblo Mountain A'ir.STWLL Neil Pei S 'i-nWt Mahogany Ri.ge ,haaesot, uSGi, Pee: enn;s *i;i train ' 6868 4 n*a.asay Holloway T4OS R34E T4OS R35E I 1405 6E T405 R37E 'I 14'R38E / i.l:irintoi "Van Hone Basin' Colony Ranch 0 U Lithe Windy Pass z SChrERRYSPR1N. 0 I 1* RO4 - - 'r Denio Basin A' tuitdIhSPIhlNn% ()Conne eme Cottonwood Creek ie;. r' Gller Cabin T4IS R37E L,aticw P ',ik 1712000901 Grassy Basin BLAiRO tih'dlM P4 IS R34E Ago 141S R36E Lung Canyon Ii Middle Canyon Oecio Cemetery East B. ring Corral Canyon ento Nevada portion of this HUC was not assessed for this project MAP # 9 - Alvord Lake Sub-basin - 5th Field HUC 1712000901 Cottonwood Creek 1 inch equals 2.25 miles High and Low Elevations BLM Land Perennial Lake Paved Roads 5th Field Watersheds BLM Wilderness - Intermittent Lake County Roads S Alvord Lake Sub-Basin BLM Wilderness Study Area Dry Lake Arterial Roads HARNEY COUNTY GIS Prnpaeod by: Bryca Mcrnz Dare: Momlu 2006 State Land Marsh "_. -

Endangered Species Facts San Joaquin Kit

Endangered SpecU.S. Environmental iesFacts Protection Agency San Joaquin Kit Fox Vulpes macrot is mutica Description and Ecology Status Endangered, listed March 11, 1967. Critical Habitat Not designated. current distribution records include the Antioch area of Contra Costa County. Appearance The average male San Joaquin kit fox measures about 32 inches in length (of which 12 inches is the Habitat Because the San Joaquin kit fox requires dens length of its tail). It stands 12 inches high at the shoulder, for shelter, protection and reproduction, a habitat’s soil and weighs about 5 pounds. The female is a little smaller. type is important. Loose-textured soils are preferable, but The San Joaquin kit fox is the smallest canid species in North modification of the burrows of other animals facilitates America (but the largest kit fox subspecies). Its foot pads denning in other soil types. The historical native vegetation of are also small and distinct from other canids in its range, the Valley was largely annual grassland (“California Prairie”) averaging 1.2 inches long and 1 inch wide. The legs are long, and various scrub and subshrub communities. Vernal pool, the body slim, and the large ears are set close together. The alkali meadows and playas still provide support habitat, but B. Moose Pet erson, U.S. Fish Serviceand Wildlife B. Moose Pet nose is slim and pointed. The tail, typically carried low and have wet soils unsuitable for denning. Some of the habitat has been converted to an agricultural patchwork of row The San Joaquin kit fox is straight, tapers slightly toward its distinct black tip. -

Desert Kit Fox CESA Petition 3-10-13

BEFORE THE CALIFORNIA FISH AND GAME COMMISSION A Petition to List the Desert Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis arsipus) as Threatened under the California Endangered Species Act Photo © CDFG 2012 CENTER FOR BIOLOGICAL DIVERSITY, PETITIONER March 10, 2013 Citation: Kadaba, Dipika, Ileene Anderson, Curt Bradley and Shaye Wolf 2013. A Petition to List the Desert Kit Fox (Vulpes macrotis arsipus) as Threatened under the California Endangered Species Act. Submitted to the California Department of Fish and Wildlife – March 2013. Pgs. 58. Table of Contents Executive Summary..............................................................................................................................4 I. Population Trends.......................................................................................................................5 II. Range and Distribution ...............................................................................................................5 III. Abundance ...................................................................................................................................8 IV. Life History..................................................................................................................................8 A. Species Description ...................................................................................................................8 B. Taxonomy...................................................................................................................................9 C. Reproduction