11 Sorbian Lower) (Upper

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Standard Languages and Language Standards

Standard Languages and Language Standards Gramley, WS 2008-09 Yiddish Divisions of Jewry Sephardim: Spanish-Portugese Jews (and exiled Jews from there) As(h)kinazim: German (or northern European) Jews Mizrhim: Northern African and Arabian Jews "Jewish" languages Commonly formed from the vernacular languages of the larger communities in which Jews lived. Ghettoization and self-segregation led to differences between the local vernaculars and Jews varieties of these languages. Linguistically different because of the addition of Hebrew words, such as meshuga, makhazor (prayer book for the High Holy Days), or beis hakneses (synagogue) Among the best known such languages are Yiddish and Ladino (the Balkans, esp. Bulgaria, Greece, Turkey, the Maghreb – Sephardic Jews expelled from Spain and Portugal in 1492). In biblical times the Jews spoke Hebrew, then Aramaic, later Greek (and so on). Today Hebrew has been revived in the form of Ivrit (= Modern Hebrew). We will be looking at Yiddish. ( ייִדיש) Yiddish The focus on Yiddish is concerned chiefly with the period prior to the Second World War and the Holocaust. Yiddish existed as a language with a wide spread of dialects: Western Yiddish • Northwestern: Northern Germany and the Netherlands • Midwestern: Central Germany • Southwestern: Southern Germany, France (including Judea-Alsatian), Northern Italy Eastern Yiddish This was the larger of the two branches, and without further explanation is what is most often meant when referring to Yiddish. • Northeastern or Litvish: the Baltic states, Belarus • Mideastern or Poylish: Poland and Central Europe • Southeastern or Ukrainish: Ukraine and the Balkans • Hungarian: Austro-Hungarian Empire Standardization The move towards standardization was concentrated most importantly in the first half of the twentieth century. -

Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate

Freistaat Sachsen State Chancellery Message and Greeting ................................................................................................................................................. 2 State and People Delightful Saxony: Landscapes/Rivers and Lakes/Climate ......................................................................................... 5 The Saxons – A people unto themselves: Spatial distribution/Population structure/Religion .......................... 7 The Sorbs – Much more than folklore ............................................................................................................ 11 Then and Now Saxony makes history: From early days to the modern era ..................................................................................... 13 Tabular Overview ........................................................................................................................................................ 17 Constitution and Legislature Saxony in fine constitutional shape: Saxony as Free State/Constitution/Coat of arms/Flag/Anthem ....................... 21 Saxony’s strong forces: State assembly/Political parties/Associations/Civic commitment ..................................... 23 Administrations and Politics Saxony’s lean administration: Prime minister, ministries/State administration/ State budget/Local government/E-government/Simplification of the law ............................................................................... 29 Saxony in Europe and in the world: Federalism/Europe/International -

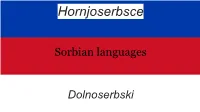

Sorbian Languages

Hornjoserbsce Sorbian languages Dolnoserbski Lusatia Sorbian: Location: Germany - Lusatia Users: 20 – 30 thousand Lower Sorbian: Upper Sorbian: Location:Niederlausitz - Location: Upper Saxony Lower Lusatia (Dolna state, Bautzen (Budysin), Luzica), Cottbus (Chósebuz) and Kamenz main town Population: around 18 Population: around 7 thousand thousand Gramma ● Dual for nouns, pronouns, Case Upper Sorb. Lower Sorb. ajdectives and verbs. Nom. žona žeńska Hand - Ruka (one) - Ruce Gen. žony žeńske (two) - Ruki (more than two) Dat. žonje žeńskej ● Upper Sorbian - seven Acc. žonu žeńsku cases Instr. ze žonu ze žeńskeju ● Lower Sorbian - six cases (no Vocativus) Loc. wo žonje wó žeńskej Voc. žono Sounds in comparison to Polish Polish sounds ć and dź in To be - Być - Biś Lower Sorbian change to ś Children - Dzieci - Źisi and ź. Group of polish sounds tr and Right - Prawy – Pšawy, pr change into tš, pś and pš. Scary - Straszny – Tšašny Pronunciation Sorbian Polish 1. č 1. cz 2. dź 2. soft version of dz 3. ě 3. beetwen polish e and i 4. h 4. mute before I and in the end of a word (bahnity) 5. kh 5. ch 6. mute in the end of the word (niósł) 6. ł 7. beetwen polish o and u 7. ó 8. rz (křidło) 8. ř 9. sz 9. š 10. before a consonant is mute (wzdać co - wyrzec 10. w się), otherwise we read it as u ( Serbow) 11. ž 11. z Status Sorbian languages are recognize by the German goverment. They have a minority language status. In the home areas of the Sorbs, both languages are officially equal to German. -

African Swine Fever in Germany

African swine fever in Germany Update on ASF situation in Brandenburg and Saxony PAFF-committee in November 2020 ASF in wild boar in Brandenburg As of November 17th 2020 → since first confirmation of ASF in September 153 positive ASF cases in wild boar have been confirmed in the eastern part of Brandenburg → On October 30th 2020 postitive carcasses have been found outside the first core area but within the infected area off the first site (districts Oder-Spree and Spree-Neisse) → Third core area was established (230 km²) → White zone around it is beeing established with wire fencing closing the gap to the already existing wire fence → Infected areas submitted as Part II areas (1649 km²) ASF in wild boar in Brandenburg Infected areas and buffer zone As of November 17th 2020 Submitted as: Part I – green Part II –light blue Seite 3 Core areas and white zones Within infected areas of Brandenburg Bleyen Neuzelle/ Sembten Core areas and white zones in Brandenburg Bleyen Friedland and Neuzelle/Sembten Epidemiological results in Brandenburg Presumably seperate disease spot in Bleyen Presumably introduction via migrating wild boar crossing the river/border in Bleyen Human introduction in Neuzelle/Sembten cannot be excluded Spread by vehicles neglectable Interviewing of residents and hunters helpfull Surveillance ASF in wild boar in Brandenburg September 10st – November 17th 2020 ASF in wild boar in Saxony As of November 17th 2020 → On October 31st 2020 one healthy shot wild boar was confirmed positive of ASF in Saxony, district of Görlitz 170 m -

The Shared Lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic

THE SHARED LEXICON OF BALTIC, SLAVIC AND GERMANIC VINCENT F. VAN DER HEIJDEN ******** Thesis for the Master Comparative Indo-European Linguistics under supervision of prof.dr. A.M. Lubotsky Universiteit Leiden, 2018 Table of contents 1. Introduction 2 2. Background topics 3 2.1. Non-lexical similarities between Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2. The Prehistory of Balto-Slavic and Germanic 3 2.2.1. Northwestern Indo-European 3 2.2.2. The Origins of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 4 2.3. Possible substrates in Balto-Slavic and Germanic 6 2.3.1. Hunter-gatherer languages 6 2.3.2. Neolithic languages 7 2.3.3. The Corded Ware culture 7 2.3.4. Temematic 7 2.3.5. Uralic 9 2.4. Recapitulation 9 3. The shared lexicon of Baltic, Slavic and Germanic 11 3.1. Forms that belong to the shared lexicon 11 3.1.1. Baltic-Slavic-Germanic forms 11 3.1.2. Baltic-Germanic forms 19 3.1.3. Slavic-Germanic forms 24 3.2. Forms that do not belong to the shared lexicon 27 3.2.1. Indo-European forms 27 3.2.2. Forms restricted to Europe 32 3.2.3. Possible Germanic borrowings into Baltic and Slavic 40 3.2.4. Uncertain forms and invalid comparisons 42 4. Analysis 48 4.1. Morphology of the forms 49 4.2. Semantics of the forms 49 4.2.1. Natural terms 49 4.2.2. Cultural terms 50 4.3. Origin of the forms 52 5. Conclusion 54 Abbreviations 56 Bibliography 57 1 1. -

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri Scholarworks User Guide August, 2020

German Dialects in Kansas and Missouri ScholarWorks User Guide August, 2020 Table of Contents INTERVIEW METHODOLOGY ................................................................................................................................. 1 THE RECORDINGS ................................................................................................................................................. 2 THE SPEAKERS ...................................................................................................................................................... 2 KANSAS ....................................................................................................................................................................... 3 MISSOURI .................................................................................................................................................................... 4 THE QUESTIONNAIRES ......................................................................................................................................... 5 WENKER SENTENCES ..................................................................................................................................................... 5 KU QUESTIONNAIRE ..................................................................................................................................................... 6 REFERENCE MAPS FOR LOCATING POTENTIAL SPEAKERS ..................................................................................... -

Text and Audio Corpus of Native Lower Sorbian Tekstowy a Zukowy Korpus Maminorěcneje Dolnoserbšćiny

Lower Sorbian Text and audio corpus of native Lower Sorbian Tekstowy a zukowy korpus maminorěcneje dolnoserbšćiny Name of language: Lower Sorbian Generic affiliation: Indo‐European, Slavic, West Slavic, Sorbian Country and region: Germany, Brandenburg, Lower Lusatia Number of speakers of native Lower Sorbi‐ an: a few hundred History Sorbian tribes were first mentioned in 631 AD and the ancestors of today’s Sorbs have settled in the region to become known as ‘Lusatia’ as early as the 6th century AD. The first written document in (Eastern) Lower Sorbian is the New Testament (in the version of Martin Luther) translated by Mikławš Jaku‐ bica in 1548. Sorbian (used as a generic term 10 years Witaj Kindergarten Sielow/Žylow, 2008; by courtesy of W. Meschkank for both Sorbian languages, Lower Sorbian and Upper Sorbian) comprises a large number of dialects. Since the 16th century, in the wake Permanent project team Challenges and importance of the of the Reformation, both languages began to Sorbian Institute (Germany) project develop a literary variety. Because of natural and forced assimilation, the language area of Dr. Hauke Bartels The biggest challenge for the Lower Sorbian Sorbian has shrunk considerably over the project head DoBeS project is the small and very fast de‐ course of the centuries. creasing number of native speakers. The con‐ Kamil Thorquindt‐Stumpf tinuity of spoken Lower Sorbian dialects is Although many dialects are already extinct or project coordinator most likely to end soon, when the few still almost extinct, today’s native dialect‐based existing native speakers have passed away. Lower Sorbian shows significant differences to Jan Meschkank With all native speakers being of the oldest the literary language taught in a few schools generation, gaining access to them or even in Lower Lusatia. -

Lusatia) and Its Role in Fe Fluxes, Precipitation and Coating of the River Bed

EGU2020-4975 https://doi.org/10.5194/egusphere-egu2020-4975 EGU General Assembly 2020 © Author(s) 2021. This work is distributed under the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 License. Mapping and quantifying groundwater inflow to the Spree River (Lusatia) and its role in Fe fluxes, precipitation and coating of the river bed. Benjamin Gilfedder1,2, Fabian Wismeth1, and Sven Frei2 1Limnologische Forschungsstation Universität Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Deutschland 2Lehrstuhl für Hydrologie Universität Bayreuth, Bayreuth, Deutschland The spatial distribution and temporal dynamics of groundwater inflow to rivers is often poorly defined but central to understanding water and matter fluxes. This is especially true for the Spree River which drains the Lusatia mining district, Brandenburg Germany. In the Spree catchment iron and sulphate fluxes to the river stem from the pyrite rich groundwater system, and the area’s history of open-pit lignite mining and re-flooding of many of these mines at the end of their lifetime. This iron flux threatens the river ecosystem, tourism in downstream communities (Spreewald) and the drinking water of Berlin. Iron is often observed as precipitates along the river bed, as well as colouring the river water yellow-brown, indicating the presence of iron (oxy)hydroxides such as ferrihydrite and goethite. In this work we have used radon as a natural groundwater tracer to delimited areas of active groundwater discharge to both the main Spree River and the Kleine Spree River to better understand the spatial destitution of groundwater input to the system. This was combined with mass-balance modelling to quantify the groundwater flux along the river using the FINIFLUX model. -

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 Weeks Program A1 to B2

Academic Plan - Flamingo Spanish School 4 weeks program A1 to B2 Basic Spanish Level A1: Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture Introduce yourself ● ● Greetings Greetings ● ● Subjects Pronouns ● Farewells ● The alphabet Unit 1 Spelling names ● Countries in South America ● ● Verb “llamarse” ● Useful expressions ● The vowels The Class Ask and give personal ● Numbers information ● ● Subject Pronouns ● Introduce someone ● Verb “ser” simple present Unit 2 (identification, origen and ● Countries ● Ask and say the nationality nationality) Identify people Demonyms The accent Cognates ● Decir que idioma(s) habla ● Demonyms ● ● ● Languages ● Say what language you ● Verb “estar” (Place) ● speak ● Verb “hablar” ● Verb “ser” (occupation or profession) ● Ask and say the occupation or profession ● The questions ● Places where people work ● Ask and answer where a ● Indefinite article Unit 3 Parts of the day Intonation in questions The occupations better person work Number and gender of the ● ● ● ● paid in Latinoamerica Occupations ● Ask and answer where a noun ● Numbers person lives ● Regular verbs * occupation or profession ● Ask and answer the time ● Present of indicative ● Interrogative pronouns ● Identify kinship ● Article determined: gender Unit 4 relationships and number Identify the gender of Verb ser. Present of ● ● Relationships Sound /r/ Do not be confused The family objects indicative (possession, ● ● ● destination, purpose) ● Express destiny, purpose and possession ● Prepositions (de, para) Week 1 Objective Grammar Vocabulary Orthography Culture ● Adjectives: gender and number Unit 5 ● Make physical and ● Adverbs of quantity (muy, personality descriptions bastante, un poco, nothing) Description of ● Adjectives ● The letter “hache” ● The Latin American family ● Express possession ● Verb “tener”. Present of people indicative ● Possessive adjectives ● Determined article ● The impersonal form “hay” ● Hay / está ● Express existence ● Interrogative pronouns (cuánto / s, cuánta / s) ● Foods Unit 6 Interact in a restaurant ● Intonation ● ● Verb “estar”. -

The Regularization of Old English Weak Verbs

Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas Vol. 10 año 2015, 78-89 EISSN 1886-6298 http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/rlyla.2015.3583 THE REGULARIZATION OF OLD ENGLISH WEAK VERBS Marta Tío Sáenz University of La Rioja Abstract: This article deals with the regularization of non-standard spellings of the verbal forms extracted from a corpus. It addresses the question of what the limits of regularization are when lemmatizing Old English weak verbs. The purpose of such regularization, also known as normalization, is to carry out lexicological analysis or lexicographical work. The analysis concentrates on weak verbs from the second class and draws on the lexical database of Old English Nerthus, which has incorporated the texts of the Dictionary of Old English Corpus. As regards the question of the limits of normalization, the solutions adopted are, in the first place, that when it is necessary to regularize, normalization is restricted to correspondences based on dialectal and diachronic variation and, secondly, that normalization has to be unidirectional. Keywords: Old English, regularization, normalization, lemmatization, weak verbs, lexical database Nerthus. 1. AIMS OF RESEARCH The aim of this research is to propose criteria that limit the process of normalization necessary to regularize the lemmata of Old English weak verbs from the second class. In general, lemmatization based on the textual forms provided by a corpus is a necessary step in lexicological analysis or lexicographical work. In the specific area of Old English studies, there are several reasons why it is important to compile a list of verbal lemmata. To begin with, the standard dictionaries of Old English, including An Anglo-Saxon Dictionary, A Concise Anglo-Saxon Dictionary and The student’s Dictionary of Anglo-Saxon are complete although they are not based on an extensive corpus of the language but on the partial list of sources given in the prefaces or introductions to these dictionaries. -

A Penn-Style Treebank of Middle Low German

A Penn-style Treebank of Middle Low German Hannah Booth Joint work with Anne Breitbarth, Aaron Ecay & Melissa Farasyn Ghent University 12th December, 2019 1 / 47 Context I Diachronic parsed corpora now exist for a range of languages: I English (Taylor et al., 2003; Kroch & Taylor, 2000) I Icelandic (Wallenberg et al., 2011) I French (Martineau et al., 2010) I Portuguese (Galves et al., 2017) I Irish (Lash, 2014) I Have greatly enhanced our understanding of syntactic change: I Quantitative studies of syntactic phenomena over time I Findings which have a strong empirical basis and are (somewhat) reproducible 2 / 47 Context I Corpus of Historical Low German (‘CHLG’) I Anne Breitbarth (Gent) I Sheila Watts (Cambridge) I George Walkden (Konstanz) I Parsed corpus spanning: I Old Low German/Old Saxon (c.800-1050) I Middle Low German (c.1250-1600) I OLG component already available: HeliPaD (Walkden, 2016) I 46,067 words I Heliand text I MLG component currently under development 3 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I MLG = West Germanic scribal dialects in Northern Germany and North-Eastern Netherlands 4 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I The rise and fall of (written) Low German I Pre-800: pre-historical I c.800-1050: Old Low German/Old Saxon I c.1050-1250 Attestation gap (Latin) I c.1250-1370: Early MLG I c.1370-1520: ‘Classical MLG’ (Golden Age) I c.1520-1850: transition to HG as in written domain I c.1850-today: transition to HG in spoken domain 5 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I Hanseatic League: alliance between North German towns and trade outposts abroad to promote economic and diplomatic interests (13th-15th centuries) 6 / 47 What is Middle Low German? I LG served as lingua franca for supraregional communication I High prestige across North Sea and Baltic regions I Associated with trade and economic prosperity I Linguistic legacy I Huge amounts of linguistic borrowings in e.g. -

Old Frisian, an Introduction To

An Introduction to Old Frisian An Introduction to Old Frisian History, Grammar, Reader, Glossary Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. University of Leiden John Benjamins Publishing Company Amsterdam / Philadelphia TM The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of 8 American National Standard for Information Sciences — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Bremmer, Rolf H. (Rolf Hendrik), 1950- An introduction to Old Frisian : history, grammar, reader, glossary / Rolf H. Bremmer, Jr. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references and index. 1. Frisian language--To 1500--Grammar. 2. Frisian language--To 1500--History. 3. Frisian language--To 1550--Texts. I. Title. PF1421.B74 2009 439’.2--dc22 2008045390 isbn 978 90 272 3255 7 (Hb; alk. paper) isbn 978 90 272 3256 4 (Pb; alk. paper) © 2009 – John Benjamins B.V. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, photoprint, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publisher. John Benjamins Publishing Co. · P.O. Box 36224 · 1020 me Amsterdam · The Netherlands John Benjamins North America · P.O. Box 27519 · Philadelphia pa 19118-0519 · usa Table of contents Preface ix chapter i History: The when, where and what of Old Frisian 1 The Frisians. A short history (§§1–8); Texts and manuscripts (§§9–14); Language (§§15–18); The scope of Old Frisian studies (§§19–21) chapter ii Phonology: The sounds of Old Frisian 21 A. Introductory remarks (§§22–27): Spelling and pronunciation (§§22–23); Axioms and method (§§24–25); West Germanic vowel inventory (§26); A common West Germanic sound-change: gemination (§27) B.