Tobacco Industry Political Influence and Tobacco Control Policy in Virginia, 1977-2009

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the United States District Court for the District Of

Case 1:16-cv-00296-JB-LF Document 132 Filed 12/21/17 Page 1 of 249 IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT FOR THE DISTRICT OF NEW MEXICO IN RE: SANTA FE NATURAL TOBACCO COMPANY MARKETING & SALES PRACTICES AND PRODUCTS LIABILITY LITIGATION No. MD 16-2695 JB/LF MEMORANDUM OPINION AND ORDER THIS MATTER comes before the Court on: (i) the Defendants’ Request for Judicial Notice in Support of Motion to Dismiss, filed November 18, 2016 (Doc. 71)(“First JN Motion”); (ii) Defendants’ Second Motion for Judicial Notice in Support of the Motion to Dismiss the Consolidated Amended Complaint, filed February 23, 2017 (Doc. 91)(“Second JN Motion”); (iii) Defendants’ Third Motion for Judicial Notice in Support of the Motion to Dismiss the Consolidated Amended Complaint, filed May 30, 2017 (Doc. 109)(“Third JN Motion”); and (iv) the Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the Consolidated Amended Complaint and Incorporated Memorandum of Law, filed February 23, 2017 (Doc. 90)(“MTD”). The Court held hearings on June 16, 2017 and July 20, 2017. The primary issues are: (i) whether the Court may consider the items presented in the First JN Motion, the Second JN Motion, and the Third JN Motion without converting the MTD into one for summary judgment; (ii) whether the Court may exercise personal jurisdiction over Reynolds American, Inc. for claims that were not brought in a North Carolina forum; (iii) whether the Federal Trade Commission’s Decision and Order, In re Santa Fe Nat. Tobacco Co., No. C-3952 (FTC June 12, 2000), filed November 18, 2016 (Doc. 71)(“Consent Order”), requiring Defendant Santa Fe Natural Tobacco Company, Inc. -

State Officials

JOURNAL OF THE SENATE -1- APPENDIX STATE OFFICIALS EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT GOVERNOR. James S. Gilmore III LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR. John H. Hager ATTORNEY GENERAL . .Mark L. Earley CHIEF OF STAFF. .M. Boyd Marcus, Jr. ADMINISTRATION, SECRETARY OF . G. Bryan Slater COMMERCE AND TRADE, SECRETARY OF . Barry E. DuVal COMMONWEALTH, SECRETARY OF . Anne P. Petera COUNSELOR TO THE GOVERNOR. Walter S. Felton, Jr. EDUCATION, SECRETARY OF . Wilbert Bryant FINANCE, SECRETARY OF. .Ronald L. Tillett HEALTH AND HUMAN RESOURCES, SECRETARY OF. Claude A. Allen NATURAL RESOURCES, SECRETARY OF . John Paul Woodley, Jr. PUBLIC SAFETY, SECRETARY OF . Gary K. Aronhalt TECHNOLOGY, SECRETARY OF . .Donald W. Upson TRANSPORTATION, SECRETARY OF . Shirley J. Ybarra LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT SENATE PRESIDENT . John H. Hager PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE. John H. Chichester CLERK . Susan Clarke Schaar HOUSE OF DELEGATES SPEAKER. .S. Vance Wilkins, Jr. CLERK . .Bruce F. Jamerson AUDITOR OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS . Walter J. Kucharski JOINT LEGISLATIVE AUDIT REVIEW COMMISSION, DIRECTOR. Philip A. Leone LEGISLATIVE AUTOMATED SYSTEMS, DIVISION OF, DIRECTOR . William E. Wilson LEGISLATIVE SERVICES, DIVISION OF, DIRECTOR. E. M. Miller, Jr. JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT SUPREME COURT OF VIRGINIA CHIEF JUSTICE. Harry L. Carrico ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. .Elizabeth B. Lacy ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. Leroy Rountree Hassell, Sr. ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. Barbara Milano Keenan ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. .Lawrence L. Koontz, Jr. ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. Cynthia D. Kinser ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. .Donald W. Lemons COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA CHIEF JUDGE . .Johanna L. Fitzpatrick JUDGE . James W. Benton, Jr. JUDGE . .Sam W. Coleman III JUDGE . Jere M. H. Willis, Jr. JUDGE . Larry G. Elder JUDGE . Richard S. Bray JUDGE . .Rosemarie Annunziata JUDGE . .Rudolph Bumgardner, III JUDGE . Robert P. Frank JUDGE . Robert J. -

Prayer Vigil at ICE Office Use-Of-Force Cases in Which an In- the Closed-Door Meeting

Pet Gazette Pages 10-11 Mount Vernon’s Hometown Newspaper • A Connection Newspaper February 23, 2017 County Names Police Auditor ichard G. Schott, a 27- Another was Ryear veteran of the FBI, creation of a was appointed by the civilian review Board of Supervisors to be Fairfax panel. The su- County’s first-ever independent pervisors ap- Photo contributed Photo police auditor. proved that The announcement of Schott’s body as well, hiring came at the board’s Feb. 14 Schott set to be a meeting. As auditor, Schott will re- nine-member port directly to the board and have group of volunteers who will re- numerous oversight responsibili- view complaints of police miscon- ties. Among them, Fairfax County duct or abuse of power. On Feb. 17, Rising Hope pastor Keary Kincannon and other religious leaders held said: During closed session Feb. 14, a prayer vigil and demonstration at the ICE field office on Prosperity Avenue in ❖ Monitoring and reviewing in- the board was scheduled to review Fairfax. ternal investigations of Police De- applications and nominees for partment officer-involved those positions. However no an- shootings, in-custody deaths and nouncement was made following Prayer Vigil at ICE Office use-of-force cases in which an in- the closed-door meeting. dividual is killed or seriously in- Board of Supervisors chairman jured. Sharon Bulova said she was Rising Hope pastor surges of searches, “targeted enforcement ac- ❖ Requesting further investiga- pleased to welcome Schott as the tions,” for undocumented immigrant criminals tions if he determines that an in- first auditor. speaks about arrests that followed executive order from President ternal investigation was deficient “In this newly established posi- Donald Trump, this action in Mount Vernon has or conclusions were not supported tion, Mr. -

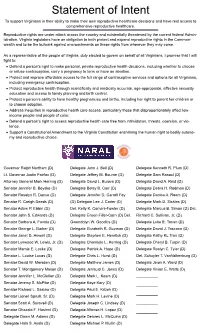

To Support Virginians in Their Ability to Make Their Own Reproductive Healthcare Decisions and Have Real Access to Comprehensive Reproductive Healthcare

Statement of Intent To support Virginians in their ability to make their own reproductive healthcare decisions and have real access to comprehensive reproductive healthcare. Reproductive rights are under attack across the country and existentially threatened by the current federal Admin- istration. Virginia legislators have an obligation to both protect and expand reproductive rights in the Common- wealth and to be the bulwark against encroachments on these rights from wherever they may come. As a representative of the people of Virginia, duly elected to govern on behalf of all Virginians, I promise that I will fight to: • Defend a person's right to make personal, private reproductive health decisions, including whether to choose or refuse contraception, carry a pregnancy to term or have an abortion. • Protect and improve affordable access to the full range of contraceptive services and options for all Virginians, including emergency contraception. • Protect reproductive health through scientifically and medically accurate, age-appropriate, effective sexuality education and access to family planning and birth control. • Protect a person’s ability to have healthy pregnancies and births, including her right to parent her children or to choose adoption. • Address inequities in reproductive health care access, particularly those that disproportionately affect low- income people and people of color. • Defend a person’s right to access reproductive health care free from intimidation, threats, coercion, or vio- lence. • Support a Constitutional Amendment to the Virginia Constitution enshrining the human right to bodily autono- my and reproductive choice. Governor Ralph Northam (D) Delegate John J. Bell (D) Delegate Kenneth R. Plum (D) Lt. Governor Justin Fairfax (D) Delegate Jeffrey M. -

2020 Virginia Capitol Connections

Virginia Capitol Connections 2020 ai157531556721_2020 Lobbyist Directory Ad 12022019 V3.pdf 1 12/2/2019 2:39:32 PM The HamptonLiveUniver Yoursity Life.Proto n Therapy Institute Let UsEasing FightHuman YourMisery Cancer.and Saving Lives You’ve heard the phrases before: as comfortable as possible; • Treatment delivery takes about two minutes or less, with as normal as possible; as effective as possible. At Hampton each appointment being 20 to 30 minutes per day for one to University Proton The“OFrapy In ALLstitute THE(HUPTI), FORMSwe don’t wa OFnt INEQUALITY,nine weeks. you to live a good life considering you have cancer; we want you INJUSTICE IN HEALTH IS THEThe me MOSTn and wome n whose lives were saved by this lifesaving to live a good life, period, and be free of what others define as technology are as passionate about the treatment as those who possible. SHOCKING AND THE MOSTwo INHUMANrk at the facility ea ch and every day. Cancer is killing people at an alBECAUSEarming rate all acr osITs ouOFTENr country. RESULTSDr. William R. Harvey, a true humanitarian, led the efforts of It is now the leading cause of death in 22 states, behind heart HUPTI becoming the world’s largest, free-standing proton disease. Those states are Alaska, ArizoINna ,PHYSICALCalifornia, Colorado DEATH.”, therapy institute which has been treating patients since August Delaware, Idaho, Kansas, Kentucky, Maine, Massachusetts, 2010. Minnesota, Montana, Nebraska, NewREVERENDHampshir DR.e, Ne MARTINw Me LUTHERxico, KING, JR. North Carolina, Oregon, Vermont, Virginia, Washington, West “A s a patient treatment facility as well as a research and education Virginia, and Wisconsin. -

<< HOPE in CRISIS 2020 ALUMNI

ALUMNI MAGAZINE • WINTER 2020 << HOPE IN CRISIS 2020 ALUMNI MEDALLION THE GREATEST SHOWMEN “ William & Mary has given me so much, I want to pass it down the line. It’s important for the future of the university.” — Betsy Calvo Anderson ’70, HON J.D. ’15, P ’00 YOUR LEGACY FOR ALL TIME COMING. “ Why do I give? I feel lucky to have a unique perspective on William & Mary. As a Muscarelle Museum of Art Foundation board member, an emeritus member of the William & Mary Law School Foundation board and a past president of the Alumni Association, I’ve seen first-hand the resources and commitment it takes to keep William & Mary on the leading edge of higher education — and how diligently the university puts our contributions to work. My late husband, Alvin ’70, J.D. ’72, would be happy to know that in addition to continuing our more than 40-year legacy of annual giving, I’ve included our alma mater in my estate plans. Although I never could have imagined when I arrived on campus at age 18 what an enormous impact William & Mary would have on my life, I also couldn’t have imagined the opportunity I would have to positively influence the lives of others.” WILLIAM & MARY For assistance with your charitable gift plans, contact OFFICE OF GIFT PLANNING Kirsten A. Kellogg ’91, Ph.D., Executive Director of Principal Gifts and Gift Planning, at (757) 221-1004 or [email protected]. giving.wm.edu/giftplanning BOLD MOMENTS DEFINE US. For Omiyẹmi, that moment was when she stopped waiting for approval to create art and started devising her own opportunities. -

State Officials

JOURNAL OF THE SENATE -1- APPENDIX STATE OFFICIALS EXECUTIVE DEPARTMENT GOVERNOR. Timothy M. Kaine LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR. .William T. “Bill” Bolling ATTORNEY GENERAL . Bill Mims CHIEF OF STAFF. .Wayne M. Turnage ADMINISTRATION, SECRETARY OF . .Viola O. Baskerville AGRICULTURE AND FORESTRY, SECRETARY OF . .Robert S. Bloxom ASSISTANT TO THE GOVERNOR FOR COMMONWEALTH PREPAREDNESS . Robert P. Crouch COMMERCE AND TRADE, SECRETARY OF . Patrick O. Gottschalk COMMONWEALTH, SECRETARY OF . Katherine K. Hanley COUNSELOR TO THE GOVERNOR. Mark Rubin EDUCATION, SECRETARY OF . Dr. Thomas R. Morris FINANCE, SECRETARY OF. Richard D. Brown HEALTH AND HUMAN RESOURCES, SECRETARY OF. Marilyn B. Tavenner NATURAL RESOURCES, SECRETARY OF . .L. Preston Bryant, Jr. PUBLIC SAFETY, SECRETARY OF . John William Marshall SENIOR ADVISOR TO THE GOVERNOR FOR WORKFORCE. Daniel G. LeBlanc TECHNOLOGY, SECRETARY OF . .Leonard M. Pomata TRANSPORTATION, SECRETARY OF . Pierce R. Homer LEGISLATIVE DEPARTMENT SENATE PRESIDENT . .William T. “Bill” Bolling PRESIDENT PRO TEMPORE. Charles J. Colgan CLERK . Susan Clarke Schaar HOUSE OF DELEGATES SPEAKER. William J. Howell CLERK AND KEEPER OF THE ROLLS OF THE COMMONWEALTH . .Bruce F. Jamerson AUDITOR OF PUBLIC ACCOUNTS . Walter J. Kucharski JOINT LEGISLATIVE AUDIT AND REVIEW COMMISSION, DIRECTOR . Philip A. Leone LEGISLATIVE AUTOMATED SYSTEMS, DIVISION OF, DIRECTOR . R. Jay Landis LEGISLATIVE SERVICES, DIVISION OF, DIRECTOR. E. M. Miller, Jr. JUDICIAL DEPARTMENT SUPREME COURT OF VIRGINIA CHIEF JUSTICE. Leroy Rountree Hassell, Sr. ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. Barbara Milano Keenan ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. .Lawrence L. Koontz, Jr. ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. Cynthia D. Kinser ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. .Donald W. Lemons ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. S. Bernard Goodwyn ASSOCIATE JUSTICE. LeRoy F. Millette, Jr. COURT OF APPEALS OF VIRGINIA CHIEF JUDGE . Walter S. Felton, Jr. -

Negativliste. Tobaksselskaber. Oktober 2016

Negativliste. Tobaksselskaber. Oktober 2016 Læsevejledning: Indrykket til venstre med fed tekst fremgår koncernen. Nedenunder, med almindelig tekst, fremgår de underliggende selskaber, som der ikke må investeres i. Alimentation Couche Tard Inc Alimentation Couche-Tard Inc Couche-Tard Inc Alliance One International Inc Alliance One International Inc Altria Group Inc Altria Client Services Inc Altria Consumer Engagement Services Inc Altria Corporate Services Inc Altria Corporate Services International Inc Altria Enterprises II LLC Altria Enterprises LLC Altria Finance Cayman Islands Ltd Altria Finance Europe AG Altria Group Distribution Co Altria Group Inc Altria Import Export Services LLC Altria Insurance Ireland Ltd Altria International Sales Inc Altria Reinsurance Ireland Ltd Altria Sales & Distribution Inc Altria Ventures Inc Altria Ventures International Holdings BV Batavia Trading Corp CA Tabacalera Nacional Fabrica de Cigarrillos El Progreso SA Industria de Tabaco Leon Jimenes SA Industrias Del Tabaco Alimentos Y Bebidas SA International Smokeless Tobacco Co Inc National Smokeless Tobacco Co Ltd Philip Morris AB Philip Morris Albania Sh pk Philip Morris ApS Philip Morris Asia Ltd Philip Morris Baltic UAB Philip Morris Belgium BVBA Philip Morris Belgium Holdings BVBA Philip Morris Belgrade doo Philip Morris BH doo Philip Morris Brasil SA Philip Morris Bulgaria EEOD Philip Morris Capital Corp Philip Morris Capital Corp /Rye Brook Philip Morris Chile Comercializadora Ltda Philip Morris China Holdings SARL Philip Morris China Management -

Extensions of Remarks Section

November 12, 2014 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks E1509 EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS HONORING MAYOR MARIAN serve so unassumingly and carry on the fine IN MEMORY OF DEPUTY DANNY DELEON GUERRERO TUDELA tradition not only of her predecessor but of the OLIVER mayors of all our islands should serve as an HON. GREGORIO KILILI CAMACHO inspiration for women, but more, should serve HON. TOM McCLINTOCK as a model for all people who aspire to serve OF CALIFORNIA SABLAN their communities. OF THE NORTHERN MARIANA ISLANDS IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Wednesday, November 12, 2014 f Wednesday, November 12, 2014 Mr. MCCLINTOCK. Mr. Speaker, I rise today Mr. SABLAN. Mr. Speaker, June 8, 2014 A TRIBUTE TO BRIGADIER along with Representative AMI BERA, Rep- marked a pivotal moment in the history of the GENERAL JAMES DEREK HILL resentative DORIS MATSUI, and Representative Northern Mariana Islands, when Marian DOUG LAMALFA, in honor of the service and Deleon Guerrero Tudela was sworn in not only HON. TOM LATHAM sacrifice of Sacramento County, California, Sheriff Deputy Danny Oliver. as the first female mayor of Saipan, but the OF IOWA first female mayor of any of our municipalities. Danny Oliver grew up in the Del Paso IN THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES Mayor Tudela assumed this position by oper- Heights neighborhood of Sacramento, where ation of law upon the untimely death of Mayor Wednesday, November 12, 2014 he graduated from Grant High School. During his youth, Danny experienced parts of the Donald Glenn Flores. Though residing at the Mr. LATHAM. Mr. Speaker, I rise today to time in the mainland United States, she honor- community that he was determined to im- recognize the retirement of Brigadier General prove. -

Actblue Virginia (PAC-12-00545) Reporting Period: 07/01/2012 Through: 09/30/2012 Page: 1 of 110

ActBlue Virginia (PAC-12-00545) Reporting Period: 07/01/2012 Through: 09/30/2012 Page: 1 of 110 Donor Information Schedule A: Direct Contributions Over $100 1. Employer or Business (If Corporate/Company Donor: N/A) 2. Type of Business(If Corporate Donor Type of Business) Date Contribution Aggregate Full Name of Contributor 3. Business Location Received This Period To Date Mailing Address of Contributor ABBOTT, DIANA 1.SELF 3606 MILLINGTON RD 2.NOT EMPLOYED 08/30/2012 $25.00 $25.00 FREE UNION, VA 22940 3.FREE UNION VA ACKERMAN, PETER 1.ST. CHRISTOPHER'S EPISCOPAL CHURCH 101 N. QUAKER LN. 2.PRIEST 09/29/2012 $25.00 $25.00 ALEXANDRIA, VA 22304 3.SPRINGFIELD VA ACUFF, KATHERINE 1.SELF 2210 CAMARGO DRIVE 2.HEALTH POLICY CONSULTANT 09/11/2012 $25.00 $25.00 CHARLOTTESVILLE, VA 22901 3.CHARLOTTESVILLE VA ADAMSON, ROBERT 1.MCENEARNEY ASSOCIATES; INC 2615 N JOHN MARSHALL DR 2.REALTOR 09/11/2012 $75.00 $75.00 ARLINGTON, VA 22207 3.ARLINGTON VA ADOFO, ADJOA 1.U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES 5408 9TH ST NW 2.COMMUNICATIONS 08/09/2012 $20.00 $20.00 WASHINGTON, DC 20011 3.WASHINGTON DC AGUILA, CESAR DEL 1.SALESFORCE.COM 126 FORTNIGHTLY BLVD 2.SALES 07/06/2012 $100.00 $200.00 HERNDON, VA 20170 3.SAN FRANCISCO CA AGUILA, CESAR DEL 1.SALESFORCE.COM 126 FORTNIGHTLY BLVD 2.SALES 07/06/2012 $100.00 $200.00 HERNDON, VA 20170 3.SAN FRANCISCO CA AGUILA, CESAR DEL 1.SALESFORCE.COM 126 FORTNIGHTLY BLVD 2.SALES 07/08/2012 $150.00 $350.00 HERNDON, VA 20170 3.SAN FRANCISCO CA AGUILAR, ESTEBAN A. -

Printmgr File

UNITED STATES SECURITIES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION Washington, D.C. 20549 FORM 6-K REPORT OF FOREIGN PRIVATE ISSUER Pursuant to Rule 13a-16 or 15d-16 under the Securities and Exchange Act of 1934 October 2, 2018 Commission File Number: 001-38159 BRITISH AMERICAN TOBACCO P.L.C. (Translation of registrant’s name into English) Globe House 4 Temple Place London WC2R 2PG United Kingdom (Address of principal executive office) Indicate by check mark whether the registrant files or will file annual reports under cover of Form 20-F or Form 40-F. Form 20-F ☒ Form 40-F ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(1): ☐ Indicate by check mark if the registrant is submitting the Form 6-K in paper as permitted by Regulation S-T Rule 101(b)(7): ☐ The information contained in this Form 6-K is incorporated by reference into the Company’s Form S-8 Registration Statements File Nos. 333-223678 and 333-219440 and related Prospectuses, as such Registration Statements and Prospectuses may be amended from time to time. British American Tobacco p.l.c. (the “Company” or “BAT”) is furnishing herewith revised financial statements in their entirety and other affected financial information which supersede the equivalent information included in the Company’s Annual Report on Form 20-F for the fiscal year ended December 31, 2017, as filed with the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (“SEC”) on March 15, 2018 (the “Form 20-F”). -

Immigration Law Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Supreme Court Preview Conferences, Events, and Lectures 2016 Section 7: Immigration Law Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Institute of Bill of Rights Law at the William & Mary Law School, "Section 7: Immigration Law" (2016). Supreme Court Preview. 260. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview/260 Copyright c 2016 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/preview VII. Election Law In This Section: New Case: 15-680 Bethune-Hill v. Virginia State Board of Elections p. 377 Synopsis and Questions Presented p. 377 “SUPREME COURT WILL WEIGH IN ON WHETHER VA. DISTRICTS ARE RACIALLY p. 435. GERRYMANDERED” Robert Barnes & Laura Vozzella “HOW RACIAL GERRYMANDERING DEPRIVES BLACK PEOPLE OF POLITICAL POWER” p. 438p Kim Soffen . “COURT REOPENS RACE AND DEATH PENALTY ISSUES” p. 441p. Lyle Denniston “VIRGINIA HOUSE DISTRICTS UPHELD” p. 443p. Travis Fain New Case: 15-1262 McCrory v. Harris p. 446 Synopsis and Questions Presented p. 447 “SUPREME COURT TO REVIEW WHETHER NORTH CAROLINA RELIED TOO p. 478 HEAVILY ON RACE IN REDISTRICTING” Jonathan Drew “NORTH CAROLINA REDISTRICTING DELAY DENIED” p. 480 Lyle Denniston “NORTH CAROLINA'S CONGRESSIONAL PRIMARIES ARE A MESS BECAUSE p. 482 OF THESE MAPS” Tom Bullock Looking Ahead: Voter Identification p. 484 “SUPREME COURT BLOCKS NORTH CAROLINA FROM RESTORING STRICT p. 485 VOTING LAW” Adam Liptak “ELECTION LITIGATION 2016: WHERE THINGS STAND” p. 488 Rick Hasen “AS NOVEMBER APPROACHES, COURTS DEAL SERIES OF BLOWS TO VOTER p.