Polynesia and Micronesia

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uncharted Seas: European-Polynesian Encounters in the Age of Discoveries

Uncharted Seas: European-Polynesian Encounters in the Age of Discoveries Antony Adler y the mid 18th century, Europeans had explored many of the world's oceans. Only the vast expanse of the Pacific, covering a third of the globe, remained largely uncharted. With the end of the Seven Years' War in 1763, England and France once again devoted their efforts to territorial expansion and exploration. Government funded expeditions set off for the South Pacific, in misguided belief that the continents of the northern hemisphere were balanced by a large land mass in the southern hemisphere. Instead of finding the sought after southern continent, however, these expeditions came into contact with what 20th-century ethnologist Douglas Oliver has identified as a society "of surprising richness, complexity, vital- ity, and sophistication."! These encounters would lead Europeans and Polynesians to develop new interpretations of the "Other:' and change their understandings of themselves. Too often in the post-colonial world, historical accounts of first contacts have glossed them as simple matters of domination and subjugation of native peoples carried out in the course of European expansion. Yet, as the historian Charles H. Long writes in his critical overview of the commonly-used term transcu!turation: It is clear that since the fifteenth century, the entire globe has become the site of hundreds of contact zones. These zones were the loci of new forms of language and knowledge, new understandings of the nature of human rela- Published by Maney Publishing (c) The Soceity for the History of Discoveries tions, and the creation and production of new forms of human community. -

The Samoan Aidscape: Situated Knowledge and Multiple Realities of Japan’S Foreign Aid to Sāmoa

THE SAMOAN AIDSCAPE: SITUATED KNOWLEDGE AND MULTIPLE REALITIES OF JAPAN’S FOREIGN AID TO SĀMOA A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI‘I AT MĀNOA IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY IN GEOGRAPHY DECEMBER 2012 By Masami Tsujita Dissertation Committee: Mary G. McDonald, Chairperson Krisnawati Suryanata Murray Chapman John F. Mayer Terence Wesley-Smith © Copyright 2012 By Masami Tsujita ii I would like to dedicate this dissertation to all who work at the forefront of the battle called “development,” believing genuinely that foreign aid can possibly bring better opportunities to people with fewer choices to achieve their life goals and dreams. iii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This dissertation is an accumulation of wisdom and support from the people I encountered along the way. My deepest and most humble gratitude extends to my chair and academic advisor of 11 years, Mary G. McDonald. Her patience and consideration, generously given time for intellectual guidance, words of encouragement, and numerous letters of support have sustained me during this long journey. Without Mary as my advisor, I would not have been able to complete this dissertation. I would like to extend my deep appreciation to the rest of my dissertation committee members, Krisnawati Suryanata, Terence Wesley-Smith, Lasei Fepulea‘i John F. Mayer, and Murray Chapman. Thank you, Krisna, for your thought-provoking seminars and insightful comments on my papers. The ways in which you frame the world have greatly helped improved my naïve view of development; Terence, your tangible instructions, constructive critiques, and passion for issues around the development of the Pacific Islands inspired me to study further; John, your openness and reverence for fa‘aSāmoa have been an indispensable source of encouragement for me to continue studying the people and place other than my own; Murray, thank you for your mentoring with detailed instructions to clear confusions and obstacles in becoming a geographer. -

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania

The Political, Security, and Climate Landscape in Oceania Prepared for the US Department of Defense’s Center for Excellence in Disaster Management and Humanitarian Assistance May 2020 Written by: Jonah Bhide Grace Frazor Charlotte Gorman Claire Huitt Christopher Zimmer Under the supervision of Dr. Joshua Busby 2 Table of Contents Executive Summary 3 United States 8 Oceania 22 China 30 Australia 41 New Zealand 48 France 53 Japan 61 Policy Recommendations for US Government 66 3 Executive Summary Research Question The current strategic landscape in Oceania comprises a variety of complex and cross-cutting themes. The most salient of which is climate change and its impact on multilateral political networks, the security and resilience of governments, sustainable development, and geopolitical competition. These challenges pose both opportunities and threats to each regionally-invested government, including the United States — a power present in the region since the Second World War. This report sets out to answer the following questions: what are the current state of international affairs, complexities, risks, and potential opportunities regarding climate security issues and geostrategic competition in Oceania? And, what policy recommendations and approaches should the US government explore to improve its regional standing and secure its national interests? The report serves as a primer to explain and analyze the region’s state of affairs, and to discuss possible ways forward for the US government. Given that we conducted research from August 2019 through May 2020, the global health crisis caused by the novel coronavirus added additional challenges like cancelling fieldwork travel. However, the pandemic has factored into some of the analysis in this report to offer a first look at what new opportunities and perils the United States will face in this space. -

Origins of Sweet Potato and Bottle Gourd in Polynesia: Pre-European Contacts with South America?

Seminar Origins of sweet potato and bottle gourd in Polynesia: pre-European contacts with South America? Dr. Andrew Clarke Allan Wilson Centre for Molecular Ecology and Evolution, Department of Anthropology, University of Auckland, New Zealand Wednesday, April 15th – 3:00 pm. Phureja Room This presentation will be delivered in English, but the slides will be in Spanish. Abstract: It has been suggested that both the sweetpotato (camote) and bottle gourd (calabaza) were introduced into the Pacific by Polynesian voyagers who sailed to South America around AD 1100, collected both species, and returned to Eastern Polynesia. For the sweetpotato, this hypothesis is well supported by archaeological, linguistic and biological evidence, but using molecular genetic techniques we are able to address more specific questions: Where in South America did Polynesians make landfall? What were the dispersal routes of the sweetpotato within Polynesia? What was the influence of the Spanish and Portuguese sweetpotato introductions to the western Pacific in the 16th century? By analysing over 300 varieties of sweet potato from the Yen Sweet Potato Collection in Tsukuba, Japan using high-resolution DNA fingerprinting techniques we are beginning to elucidate specific patterns of sweetpotato dispersal. This presentation will also include discussion of the Polynesian bottle gourd, and our efforts to determine whether it is of South American or Asian origin. Understanding dispersal patterns of both the sweetpotato and bottle gourd is adding to our knowledge of human movement in the Pacific. It also shows how germplasm collections such as those maintained by the International Potato Center can be used to answer important anthropological questions. -

Disability, Activism, and Education in Samoa, 1970-1980

Syracuse University SURFACE Dissertations - ALL SURFACE December 2015 Trying Times: Disability, Activism, and Education in Samoa, 1970-1980 Juliann Anesi Syracuse University Follow this and additional works at: https://surface.syr.edu/etd Part of the Education Commons Recommended Citation Anesi, Juliann, "Trying Times: Disability, Activism, and Education in Samoa, 1970-1980" (2015). Dissertations - ALL. 418. https://surface.syr.edu/etd/418 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the SURFACE at SURFACE. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations - ALL by an authorized administrator of SURFACE. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Abstract In the 1970s and 1980s, Samoan women organizers established Aoga Fiamalamalama and Loto Taumafai, which were educational institutions in Samoa, an island in the Pacific. Establishing these schools for students with intellectual and physical disabilities, excluded from attending formal schools based on the misconception that they were "uneducable". In this project, I seek to understand how parent advocates, allies, teachers, women organizers, women with disabilities, and former students of these schools understood disability, illness, inclusive education, and community organizing. Through interviews and analysis of archival documents, stories, cultural myths, legends related to people with disabilities, pamphlets, and newspaper media, I examine how disability advocates and people with disabilities interact with educational and cultural discourses to shape programs for the empowerment of people with disabilities. I argue that the notions of ma’i (sickness), activism, and disability inform the Samoan context, and by understanding, their influence on human rights and educational policies can inform our biased attitudes on ableism and normalcy. -

Chapter 5. Social and Economic Environment 5.1 Cultural Resources

Rose Atoll National Wildlife Refuge Comprehensive Conservation Plan Chapter 5. Social and Economic Environment 5.1 Cultural Resources Archaeological and other cultural resources are important components of our nation’s heritage. The Service is committed to protecting valuable evidence of plant, animal, and human interactions with each other and the landscape over time. These may include previously recorded or yet undocumented historic, cultural, archaeological, and paleontological resources as well as traditional cultural properties and the historic built environment. Protection of cultural resources is legally mandated under numerous Federal laws and regulations. Foremost among these are the NHPA, as amended, the Antiquities Act, Historic Sites Act, Archaeological Resources Protection Act, as amended, and Native American Graves Protection and Repatriation Act. Additionally, the Refuge seeks to maintain a working relationship and consult on a regular basis with villages that are or were traditionally tied to Rose Atoll. 5.1.1 Historical Background The seafaring Polynesians settled the Samoan Archipelago about 3,000 years ago. They are thought to have been from Southeast Asia, making their way through Melanesia and Fiji to Samoa and Tonga. They brought with them plants, pigs, dogs, chickens, and likely the Polynesian rat. Most settlement occurred in coastal areas and other islands, resulting in archaeological sites lost to ocean waters. Early archaeological sites housed pottery, basalt flakes and tools, volcanic glass, shell fishhooks and ornaments, and faunal remains. Stone quarries (used for tools such as adzes) have also been discovered on Tutuila and basalt from Tutuila has been found on the Manu’a Islands. Grinding stones have also been found in the Manu’a Islands. -

Granting Samoans American Citizenship While Protecting Samoan Land and Culture

MCCLOSKEY, 10 DREXEL L. REV. 497.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 5/14/18 2:11 PM GRANTING SAMOANS AMERICAN CITIZENSHIP WHILE PROTECTING SAMOAN LAND AND CULTURE Brendan McCloskey* ABSTRACT American Samoa is the only inhabited U.S. territory that does not have birthright American citizenship. Having birthright American citizenship is an important privilege because it bestows upon individ- uals the full protections of the U.S. Constitution, as well as many other benefits to which U.S. citizens are entitled. Despite the fact that American Samoa has been part of the United States for approximately 118 years, and the fact that American citizenship is granted automat- ically at birth in every other inhabited U.S. territory, American Sa- moans are designated the inferior quasi-status of U.S. National. In 2013, several native Samoans brought suit in federal court argu- ing for official recognition of birthright American citizenship in American Samoa. In Tuaua v. United States, the U.S. Court of Ap- peals for the D.C. Circuit affirmed a district court decision that denied Samoans recognition as American citizens. In its opinion, the court cited the Territorial Incorporation Doctrine from the Insular Cases and held that implementation of citizenship status in Samoa would be “impractical and anomalous” based on the lack of consensus among the Samoan people and the democratically elected government. In its reasoning, the court also cited the possible threat that citizenship sta- tus could pose to Samoan culture, specifically the territory’s commu- nal land system. In June 2016, the Supreme Court denied certiorari, thereby allowing the D.C. -

In the Supreme Court of the United States

No. 15-981 In the Supreme Court of the United States LENEUOTI FIAFIA TUAUA, ET AL., PETITIONERS v. UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, ET AL. ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT BRIEF FOR THE FEDERAL RESPONDENTS IN OPPOSITION DONALD B. VERRILLI, JR. Solicitor General Counsel of Record BENJAMIN C. MIZER Principal Deputy Assistant Attorney General MARK B. STERN PATRICK G. NEMEROFF Attorneys Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 [email protected] (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether the Fourteenth Amendment’s Citizenship Clause, which provides that “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States, and subject to the jurisdiction thereof, are citizens of the United States,” U.S. Const. Amend. XIV, § 1, Cl. 1, confers United States citizenship on individuals born in American Samoa. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below .............................................................................. 1 Jurisdiction .................................................................................... 1 Statement ...................................................................................... 2 Argument ....................................................................................... 8 Conclusion ................................................................................... 22 TABLE OF AUTHORITIES Cases: Afroyim v. Rusk, 387 U.S. 253 (1967) ................................. 20 Armstrong v. United States, 182 U.S. 243 (1901) ............. -

THE LIMITS of SELF-DETERMINATION in OCEANIA Author(S): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol

THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Author(s): Terence Wesley-Smith Source: Social and Economic Studies, Vol. 56, No. 1/2, The Caribbean and Pacific in a New World Order (March/June 2007), pp. 182-208 Published by: Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies, University of the West Indies Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/27866500 . Accessed: 11/10/2013 20:07 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of the West Indies and Sir Arthur Lewis Institute of Social and Economic Studies are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to Social and Economic Studies. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 133.30.14.128 on Fri, 11 Oct 2013 20:07:57 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions Social and Economic Studies 56:1&2 (2007): 182-208 ISSN:0037-7651 THE LIMITS OF SELF-DETERMINATION IN OCEANIA Terence Wesley-Smith* ABSTRACT This article surveys processes of decolonization and political development inOceania in recent decades and examines why the optimism of the early a years of self government has given way to persistent discourse of crisis, state failure and collapse in some parts of the region. -

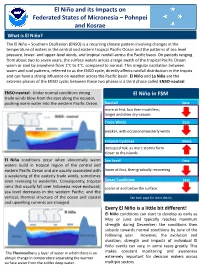

El Niño and Its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei And

El Niño and its Impacts on Federated States of Micronesia – Pohnpei and Kosrae What is El Niño? The El Niño – Southern Oscillation (ENSO) is a recurring climate pattern involving changes in the temperature of waters in the central and eastern tropical Pacific Ocean and the patterns of sea level pressure, lower- and upper-level winds, and tropical rainfall across the Pacific basin. On periods ranging from about two to seven years, the surface waters across a large swath of the tropical Pacific Ocean warm or cool by anywhere from 1°C to 3°C, compared to normal. This irregular oscillation between warm and cool patterns, referred to as the ENSO cycle, directly affects rainfall distribution in the tropics and can have a strong influence on weather across the Pacific basin. El Niño and La Niña are the extreme phases of the ENSO cycle; between these two phases is a third phase called ENSO-neutral. ENSO-neutral: Under normal conditions strong El Niño in FSM trade winds blow from the east along the equator, pushing warm water into the western Pacific Ocean. Rainfall Less more at first, but then much less; longer and drier dry-season Trade Winds Less weaker, with occasional westerly winds Tropical Cyclones More increased risk, as more storms form closer to the islands El Niño conditions occur when abnormally warm Sea Level Less waters build in tropical region of the central and eastern Pacific Ocean and are usually associated with lower at first, then gradually recovering a weakening of the easterly trade winds, sometimes even reversing to westerlies. -

A Failed Relationship: Micronesia and the United States of America Eddie Iosinto Yeichy*

A Failed Relationship: Micronesia and the United States of America Eddie Iosinto Yeichy* I. INTRODUCTION ................................................................................. 172 II. THE RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN MIRCORONESIA AND THE UNITED STATES .............................................................................................. 175 A. Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands ........................................ 175 B. Compact of Free Association.................................................... 177 III. UNITED STATES FAILURE TO FULFILL ITS LEGAL DUTIES .................. 178 A. Historical Failures ................................................................... 178 B. Modern Failures ....................................................................... 184 C. Proposed Truths for United States Failure ............................... 186 IV. PROPOSED SOLUTION: SOCIAL HEALING THROUGH JUSTICE FRAMEWORK .................................................................................... 186 A. Earlier Efforts of Reparation: Courts Tort Law Monetary Model ........................................................................................ 187 B. Professor Yamamoto’s Social Healing Through Justice Framework ............................................................................... 188 C. Application: Social Healing Through Justice Framework ....... 191 D. Clarifying COFA Legal Status .................................................. 193 V. CONCLUSION ................................................................................... -

Jesuitvolunteers.Org CHUUK, MICRONESIA Volunteer

CHUUK, MICRONESIA MAU PIAILUG HOUSE JV Presence in Microneisa since 1985 Mailing Address Jesuit Volunteers [JV’s Name] Xavier High School PO Box 220 Chuuk, FSM 96942 Ph: 011-691-330-4266 Volunteer Accompaniment JVC Coordinator Emily Ferron (FJV Chuuk, 2010-12) [email protected] Local Formation Team Fr. Tom Benz, SJ Fr. Dennis Baker, SJ In-Country Coordinator Support Person [email protected] [email protected] Overview The term Micronesia is short for the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM), and refers more accurately to geographic/cultural region (not dissimilar to terms such as Central America or the Caribbean). Micronesia contains four main countries (and a few little ones but we’ll focus on the main four): Republic of the Marshall Islands, Federated States of Micronesia, Republic of Palau, and Republic of Kiribati. Within Micronesia, there are many different cultural groups. For instance in FSM, there are four states, each uniquely different (culturally). Within one of those states, one can find different cultural groups as well (outer islands vs lagoon or main island). In some placements JVs have the opportunity to interact with many of these different culture groups from outside of the host island. For example, Xavier High School (in Chuuk), the student and staff/teacher population is truly international and representative of many of these cultural groups. The FSM consists of some 600 islands grouped into four states: Kosrae, Pohnpei, Chuuk (Truk) and Yap. Occupying a very small total land mass, it is scattered over an ocean expanse five times the size of France. With a population of 110,000, each cultural group has its own language, with English as the common language.