OWL MLA Formatting Exemplar

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

August 2015 Find Your Revolutionary War Park

Subscribe Share Past Issues Translate RSS WashingtonRochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historical Trail View this email in your browser August 2015 Like us on Facebook! Check out our Website! This Month's Issue Find Your Revolutionary War On August 25, 2015, we celebrated the 99th birthday of Park the National Park Service! Look for ways to find your Connecticut Bike park as we gear up to celebrate the centennial. Ride on the NHT New York Wayside Exhibits Find Your Revolutionary War Park Maryland Trails Coordination Each month we will be highlighting one of the many Delaware Trail National Parks that share the story of the Washington Coordination Rochambeau Revolutionary Route NHT. See the Treaty of Paris Places to Go section of the website to find your festival in Annapolis, Revolutionary War park. MD 7th Annual W3R® Celebration and Free Valley Forge National Historical Park Ice Cream Social Marcus Hook, PA Located about twenty miles northwest of Philadelphia, Valley Forge National Historical Park preserves the 6th Annual grounds of the Continental Army's most legendary Revolutionary War winter encampment of 17771778. The park Weekend at Fishkill Supply Depot in NY commemorates the army's perseverance to overcome the hardships of that winter and their transformation into October 18, 2015 a professional fighting force. On May 6th, 1778 the W3RUS Board army celebrated the French Alliance on the Grand Meeting in Yorktown Parade grounds of the encampment. This alliance brought General Rochambeau and his French army to the United States two years later. More than 20,000 National Park Service employees help care for America’s National Parks, Heritage Areas, Trails, Wild & Scenic Rivers, and other affiliated, related areas and programs. -

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown

Citizens and Soldiers in the Siege of Yorktown Introduction During the summer of 1781, British general Lord Cornwallis occupied Yorktown, Virginia, the seat of York County and Williamsburg’s closest port. Cornwallis’s commander, General Sir Henry Clinton, ordered him to establish a naval base for resupplying his troops, just after a hard campaign through South and North Carolina. Yorktown seemed the perfect choice, as at that point, the river narrowed and was overlooked by high bluffs from which British cannons could control the river. Cornwallis stationed British soldiers at Gloucester Point, directly opposite Yorktown. A British fleet of more than fifty vessels was moored along the York River shore. However, in the first week of September, a French fleet cut off British access to the Chesapeake Bay, and the mouth of the York River. When American and French troops under the overall command of General George Washington arrived at Yorktown, Cornwallis pulled his soldiers out of the outermost defensive works surrounding the town, hoping to consolidate his forces. The American and French troops took possession of the outer works, and laid siege to the town. Cornwallis’s army was trapped—unless General Clinton could send a fleet to “punch through” the defenses of the French fleet and resupply Yorktown’s garrison. Legend has it that Cornwallis took refuge in a cave under the bluffs by the river as he sent urgent dispatches to New York. Though Clinton, in New York, promised to send aid, he delayed too long. During the siege, the French and Americans bombarded Yorktown, flattening virtually every building and several ships on the river. -

FISHKILLISHKILL Mmilitaryilitary Ssupplyupply Hubhub Ooff Thethe Aamericanmerican Rrevolutionevolution

Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 1234 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 This material is based upon work assisted by a grant from the Department of Interior, National Park Service. Any opinions, fi ndings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily refl ect the views of the Department of the Interior. FFISHKILLISHKILL MMilitaryilitary SSupplyupply HHubub ooff tthehe AAmericanmerican RRevolutionevolution 11776-1783776-1783 “...the principal depot of Washington’s army, where there are magazines, hospitals, workshops, etc., which form a town of themselves...” -Thomas Anburey 1778 Friends of the Fishkill Supply Depot A Historical Overview www.fi shkillsupplydepot.org Cover Image: Spencer Collection, New York Public Library. Designed and Written by Hunter Research, Inc., 2016 “View from Fishkill looking to West Point.” Funded by the American Battlefi eld Protection Program Th e New York Public Library Digital Collections. 1820. Staples® Print Solutions HUNRES_1518351_BRO01 QA6 5678 CYANMAGENTAYELLOWBLACK 06/6/2016 Fishkill Military Supply Hub of the American Revolution In 1777, the British hatched a scheme to capture not only Fishkill but the vital Fishkill Hudson Valley, which, if successful, would sever New England from the Mid- Atlantic and paralyze the American cause. The main invasion force, under Gen- eral John Burgoyne, would push south down the Lake Champlain corridor from Distribution Hub on the Hudson Canada while General Howe’s troops in New York advanced up the Hudson. In a series of missteps, Burgoyne overestimated the progress his army could make On July 9, 1776, New York’s Provincial Congress met at White Plains creating through the forests of northern New York, and Howe deliberately embarked the State of New York and accepting the Declaration of Independence. -

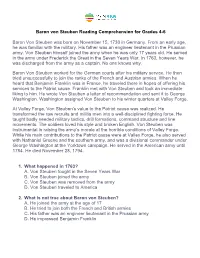

Baron Von Steuben Reading Comprehension for Grades 4-6

Baron von Steuben Reading Comprehension for Grades 4-6 Baron Von Steuben was born on November 15, 1730 in Germany. From an early age, he was familiar with the military. His father was an engineer lieutenant in the Prussian army. Von Steuben himself joineD the army when he was only 17 years old. He serveD in the army unDer FreDerick the Great in the Seven Years War. In 1763, however, he was DischargeD from the army as a captain. No one knows why. Baron Von Steuben workeD for the German courts after his military service. He then trieD unsuccessfully to join the ranks of the French anD Austrian armies. When he heard that Benjamin Franklin was in France, he traveled there in hopes of offering his services to the Patriot cause. Franklin met with Von Steuben and took an immediate liking to him. He wrote Von Steuben a letter of recommenDation anD sent it to George Washington. Washington assigneD Von Steuben to his winter quarters at Valley Forge. At Valley Forge, Von Steuben’s value to the Patriot cause was realizeD. He transformeD the raw recruits anD militia men into a well-disciplined fighting force. He taught baDly neeDeD military tactics, drill formations, commanD structure anD line movements. The solDiers loveD his style anD broken English. Von Steuben was instrumental in raising the army’s morale at the horrible conDitions of Valley Forge. While his main contributions to the Patriot cause were at Valley Forge, he also serveD with Nathaniel Greene anD the southern army, anD was a Divisional commanDer under George Washington at the Yorktown campaign. -

The British Surrender Their Armies to General Washington After Their Defeat at Your Town in Virginia, Octorber 1781

Library of Congress Figure 1: The British surrender their Armies to General Washington after their defeat at Your Town in Virginia, Octorber 1781. 48 ARLINGTON 1-IISTORICA L MAGAZINE The Arlington House Engravings of the British Surrender at Yorktown: Too Often Overlooked? BY DEAN A. DEROSA In the morning room and in the second-floor hall ofArlington House, The Robert E. Lee Memorial (the US National Park Service historical site on the grounds ofArlington National Cemetery), hang two framed engravings, entitled "The British Surrendering their Arms to Gen. Washington after their Defeat at Yorktown in Virginia, October 1781." The two art pieces, first published in 1819, are drawn by John Francis Renault and engraved by Tanner, Vallance, Kearny & Co. The morning room engraving is in color, while the second floor engraving is inscribed in black ink (Figure 1). The caption at the base of the two engravings reads, "To the defenders of American independence, this print is most respectfully inscribed by their fellow citizen, Jn. Fcis. Renault, assistant secretary to the Count de Grass, and engineer to the French Army, at the siege of York." Thus, the twin engravings are drawn by a participant in the Siege of Yorktown, if not also a witness to the historic British surrender and subsequent surrender ceremony, which for all intents and purposes ended major hostilities during the American Revolution. The allegorical background of the engravings depicts not only the field upon which the British, Continental, and French armies stood during the sur render ceremony, but also a number of classical images and symbols of human discord, victory, and liberty, described in an 1804 prospectus apparently in reference to an early, circa 1810-1815 version of the Renault drawing (Figure 2) upon which the published engraving would eventually be based, that are largely lost upon us today. -

FALL 2015 DISPATCH Newsletter of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, an Educational Institution of the Commonwealth of Virginia

FALL 2015 DISPATCH Newsletter of the Jamestown-Yorktown Foundation, an educational institution of the Commonwealth of Virginia American Revolution Museum at Yorktown Three-Month ‘Botanical Galleries and Film Previewed in New Virginia’ Exhibit Exhibit at Yorktown Victory Center Opens December 5 A new exhibit at the The artifact exhibit at Jamestown Settlement Yorktown Victory Center includes portraits of The beauty and variety of Virginia plant provides a multimedia, American Loyalist life is showcased in a three-month exhibit interactive encounter with and noted scientist opening December 5 at Jamestown Settlement. the permanent exhibition Benjamin Thompson “Clayton & Catesby: Botanical Virginia” ex- galleries and introductory and British Admiral plores documentation of native plants by natu- film that will premiere Richard Howe, a paint- ralist Mark Catesby and botanist John Clayton in conjunction with the ing of the 1782 naval in the 18th century and the Flora of Virginia museum’s transition to Battle of the Saintes, Project in the 21st century. American Revolution British and American On loan from the Garden Club of Virginia, Museum at Yorktown in swords and firearms, 17 period hand-colored engravings created from late 2016. objects bearing slogans A selection of 18th-century artifacts that will be Catesby’s watercolor paintings of American The future galleries and symbols of the exhibited in the American Revolution Museum flora and are under construction at Yorktown galleries is on exhibit in “Creating Revolutionary era, and fauna, will Our New Museum.” in a 22,000-square- American-made furni- be exhibited foot space within an ture and silver objects. alongside a 80,000-square-foot building that opened in “Creating Our New Museum” also 1762 edition March, representing a midpoint milestone in engages visitors in the making of Liberty of Flora Vir- the transformation of the Yorktown Victory Fever, the introductory film to be shown in ginica, based Center into American Revolution Museum at the 170-seat museum theater, with interactive on Clayton’s Yorktown. -

Lesson Title: Hamilton's

Lesson Title: Hamilton’s War Grade Levels : 9-12 Time Allotment: Three 45-minute class periods Overview: This high school lesson plan uses video clips from REDISCOVERING ALEXANDER HAMILTON and a website featuring interactive animations of Revolutionary War battles to explore Alexander Hamilton’s military career in three different engagements: The Battle for New York The Battle of Princeton, and the Siege of Yorktown. The Introductory Activity dispels the common misconception that the Revolution was primarily fought by “minutemen” militiamen using guerilla tactics against the British, and establishes the primary role of the Continental Army in the American war effort. The Learning Activities uses student organizers to focus students’ online exploration of the battles of New York, Princeton, and Yorktown, focusing on Alexander Hamilton’s role. The Culminating Activity challenges students to create their own organizer for a different Revolutionary War battle. This lesson is best used during a unit on the American Revolution, after the key causes for the conflict have been established. Subject Matter: History Learning Objectives: Students will be able to: • Distinguish between “irregular” and “regular” military forces in the 18 th century and outline their relative merits • Explain the context and consequences for the battles of New York, Princeton, and Yorktown • Describe the general course of events in each of these actions, noting key turning points • Discuss how historical fact can sometimes be distorted or embellished for effect • Outline -

Maryland in the American Revolution

382-MD BKLT COVER fin:382-MD BKLT COVER 2/13/09 2:55 PM Page c-4 Maryland in the Ame rican Re volution An Exhibition by The Society of the Cincinnati Maryland in the Ame rican Re volution An Exhibition by The Society of the Cincinnati Anderson House Wash ingt on, D .C. February 27 – September 5, 2009 his catalogue has been produced in conjunction with the exhibition Maryland in the American Revolution on display fTrom February 27 to September 5, 2009, at Anderson House, the headquarters, library, and museum of The Society of the Cincinnati in Washington, D.C. The exhibition is the eleventh in a series focusing on the contributions to the e do most Solemnly pledge American Revolution made by the original thirteen states ourselves to Each Other and France. W & to our Country, and Engage Generous support for this exhibition and catalogue was provided by the Society of the Cincinnati of Maryland. ourselves by Every Thing held Sacred among Mankind to Also available: Massachusetts in the American Revolution: perform the Same at the Risque “Let It Begin Here” (1997) of our Lives and fortunes. New York in the American Revolution (1998) New Jersey in the American Revolution (1999) — Bush River Declaration Rhode Island in the American Revolution (2000) by the Committee of Observation, Connecticut in the American Revolution (2001) Delaware in the American Revolution (2002) Harford County, Maryland Georgia in the American Revolution (2003) March 22, 1775 South Carolina in the American Revolution (2004) Pennsylvania in the American Revolution (2005) North Carolina in the American Revolution (2006) Text by Emily L. -

Lafayette's Visit to Fort Monroe in 1824 As Guest Of

Lafayette’s visit to Fort Monroe in 1824 as Guest of the Nation Marie-Joseph Paul Yves Roch Gilbert du Motier (6 September 1757 – 20 May 1834) By W. Robert Kelly, Historian Casemate Museum Fort Monroe Authority 20 Bernard Road Fort Monroe, Virginia 23651 [email protected] 757-690-8064 In 1824 President James Monroe, the last of the founding-father Presidents, invited Marquis de Lafayette, the last surviving general of the Revolutionary War, to visit the United States, as an official “Guest of the Nation.” Forty-eight years had passed since the signing of the Declaration of Independence and forty-three since the British surrender at Yorktown. As the generation of Revolutionary War veterans passed away, fewer and fewer Americans remembered the bloody struggle for liberty and freedom from England. President Monroe recognized that it was a crucial time in the country’s history. He felt it was important for the younger generation to recognize that freedom and democracy had come at a great cost. The President looked to Lafayette, the hero of both France and America to return and remind Americans of the sacrifices and heroism of the time. In the summer of 1777 wealthy French aristocrat Marquis de Lafayette, captivated with the ongoing American struggle for independence, used his personal wealth to purchase a ship and sail to America. Volunteering in the Continental Army, the nineteen-year-old Lafayette soon earned the command of a division and the high respect of his American soldiers. He was wounded at the Battle of Brandywine in 1777, accompanied General Washington at Valley Forge that winter, escaped capture by Lord Cornwallis at Richmond and was with Washington during the decisive Yorktown campaign in 1781. -

The War Is Won

The War Is Won : How did the Battle of : Yorktown lead to American Dlar!J :.................. American independence?..... At the Battle of Yorktown, a Pennsylvania Reading Guide soldier named Ebenezer Denny saw a Content Vocabulary drummer boy on the British side beat a ratify (p. 177) ambush (p. 178) Academic Vocabulary signal for a meeting The cannon fire strategy (p. 175) pursue (p. 177) immediately stopped. From the British lines Key People and Events came an officer. Then an officer from the Comte de Rochambeau (p. 175) Fran(:ois de Grasse (p. 175) American side ran to meet him. Denny Battle of Yorktown (p. 176) wrote in his journal, "Firing ceased Benjamin Franklin (p. 177) John Adams (p. 177) totally . ... I never heard a drum equal to John Jay (p. 177) it-the most delightful music to us all." Treaty of Paris (p. 177) -from Record of Upland, and Reading Strategy Denny's Military Journal Taking Notes As you read, use a diagram like the one below to list the forces that met Cornwallis at Yorktown. qp Victory at Yorktown close eye on the British army based in New York that General Clinton commanded. IMMIQ@i Washington's complicated battle plan Washington planned to attack Clinton's army led to the important American victory at Yorktown. as soon as the second French fleet arrived. He History and You How important is planning to the had to wait a year to put this plan into action. successful outcome of a project? Read to learn how The French fleet did not set sail for America Washington's planning helped the Americans win an until the summer of 1781. -

Find Your Revolutionary War Park

Subscribe Share Past Issues Translate RSS WashingtonRochambeau Revolutionary Route National Historical Trail View this email in your browser December 2015 Like our newsletter? Pass this on to your Find Your Revolutionary War Park family and friends and ask them to subscribe! Each month we will be highlighting one of the many Subscribe Revolutionary War parks that share the story of the WashingtonRochambeau Revolutionary Route NHT. See the Places to Go section of the website to find your Revolutionary Like us on War park. Facebook! Check out our Website! Old Barracks Museum The Old Barracks was build in 1758 to house British soldiers during the French and Indian War. At the outbreak of the American Revolution, American soldiers used it until the fall of This 1776 when the British Army occupied much of northern New Month's Jersey. In December, 1776, Hessian troops occupying Issue Trenton used the barracks until they were attacked by the Continental Army at first Battle of Trenton on December 26, Find Your 1776. Washington's victory forced the surrender of most of Revolutionary War Park Hessian garrison. After the Battle of Trenton, the Barracks became an army hospital as many soldiers and supplies Old Barracks passed through Trenton until the end of the war. The last Highlights of soldiers in the Barracks may have been sick and wounded the Month soldiers from the siege of Yorktown in 1781. New York: 2016 Heritage Development Grants Maryland Trails Coordination Delaware Trail Coordination New Jersey Trail Coordination Pennsylvania Trail Coordination The Old Barracks in Trenton, New Jersey Additional NPS photo Information Gloucester County, Virginia The Museum of the American Highlights of the Month Revolution The American Revolution Institute of the Society of the Washington's Crossing Cincinnati Plan Ahead for the 250th Anniversary of the American Revolution Read about the Revolution George Washington’s daring 1776 Christmas Day crossing of the Delaware River and defeat of the Hessians in Trenton is considered a turning point in the Revolutionary War. -

When Freedom Wore a Red Coat

1 2014 Harmon Memorial Lecture “Abandoned to the Arts & Arms of the Enemy”: Placing the 1781 Virginia Campaign in Its Racial and Political Context by Gregory J. W. Urwin Professor of History Temple University Research for this lecture was funded in part by an Earhart Foundation Fellowship on American History from the William L. Clements Library, University of Michigan; a Tyree-Lamb Fellowship, Society of the Cincinnati; a Mellon Research Fellowship from the Virginia Historical Society; and two Summer Research Awards from Temple University. 1 2 On October 25, 1781 – just six days after Gen. George Washington attained the apex of his military career by forcing the surrender of a British army at Yorktown, Virginia – he issued an order to his troops that has been scrupulously ignored by historians of the American Revolution. Washington directed his officers and “persons of every denomination concerned” to apprehend the “many Negroes and Mulattoes” found in and around Yorktown and consign them to guard posts on either side of the York River. There free blacks would be separated from runaway slaves who had sought freedom with the British, and steps taken to return the latter to their masters. In other words, Washington chose the moment he achieved the victory that guaranteed American independence to convert his faithful Continentals into an army of slave catchers.1 This is not the way Americans like to remember Yorktown. We prefer the vision President Ronald Reagan expressed during the festivities marking the bicentennial of that celebrated turning point thirty-three years ago. Reagan described Yorktown to a crowd of 60,000 as “a victory for the right of self-determination.