Preaching to the Choir 1-23.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pat Adams Selected Solo Exhibitions

PAT ADAMS Born: Stockton, California, July 8, 1928 Resides: Bennington, Vermont Education: 1949 University of California, Berkeley, BA, Painting, Phi Beta Kappa, Delta Epsilon 1945 California College of Arts and Crafts, summer session (Otis Oldfield and Lewis Miljarik) 1946 College of Pacific, summer session (Chiura Obata) 1948 Art Institute of Chicago, summer session (John Fabian and Elizabeth McKinnon) 1950 Brooklyn Museum Art School, summer session (Max Beckmann, Reuben Tam, John Ferren) SELECTED SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2017 Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont 2011 National Association of Women Artists, New York 2008 Zabriskie Gallery, New York 2005 Zabriskie Gallery, New York, 50th Anniversary Exhibition: 1954-2004 2004 Bennington Museum, Bennington, Vermont 2003 Zabriskie Gallery, New York, exhibited biennially since 1956 2001 Zabriskie Gallery, New York, Monotypes, exhibited in 1999, 1994, 1993 1999 Amy E. Tarrant Gallery, Flyn Performing Arts Center, Burlington, Vermont 1994 Jaffe/Friede/Strauss Gallery, Dartmouth College, Hanover, New Hampshire 1989 Anne Weber Gallery, Georgetown, Maine 1988 Berkshire Museum, Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Retrospective: 1968-1988 1988 Addison/Ripley Gallery, Washington, D.C. 1988 New York Academy of Sciences, New York 1988 American Association for the Advancement of Science, Washington, D.C. 1986 Haggin Museum, Stockton, California 1986 University of Virginia, Charlottesville, Virginia 1983 Image Gallery, Stockbridge, Massachusetts 1982 Columbia Museum of Art, University of South Carolina, Columbia, -

SYLLABUS Printmaking III ARTS 4355-01 Lamar University, SPRING

SYLLABUS Printmaking III ARTS 4355-01 Lamar University, SPRING 2018 TR 2:20-5:15PM , Room # 101 Associate Professor Xenia Fedorchenko Office hours by appointment and: TR 10AM-11AM Office Room # 101A; Ext. 8914 e-mail: [email protected] COURSE DESCRIPTION This course is a continuation of Printmaking II with a focus in combining new and previously learnt techniques with individually selected content. COURSE CONTENT Students will continue to learn about Printmaking through assigned readings, demonstrations of techniques, hands-on experience, and self-directed research. Students will work on plates or stones incorporating both hand-drawn and basic photographic imagery. This course is designed to encourage experimentation with the processes covered. Understanding of presenting ones work to a group, writing a statement, safe studio practices, press characteristics and operation, various ink traits (water-based, intaglio and lithographic inks), comparative qualities of diverse papers and studio equipment (rollers, brayers, etc) as they relate to ones oeuvre will be gained. Further study will occur through a series of incrementally challenging projects outside of class. Students should allow for customization of the semester’s assignments to their own artistic inquiries. Further study will also occur in the form of time spent in the library or through gallery visits. At the end of the semester, students will have the skills and visual vocabulary necessary to create unique and editioned prints that coherently combine technique and content. STUDENT LEARNING OUTCOMES At the end of this course students should be able to: −Understand and utilize various intaglio, monoprinting and planographic matrix-producing techniques. −Gain an in-depth understanding of a chosen process within printmaking −Understand color mixing and color interactions in printmaking and apply these to various printing processes. -

Woodcuts to Wrapping Paper: Concepts of Originality in Contemporary Prints Alison Buinicky Dickinson College

Dickinson College Dickinson Scholar Student Scholarship & Creative Works By Year Student Scholarship & Creative Works 1-28-2005 Woodcuts to Wrapping Paper: Concepts of Originality in Contemporary Prints Alison Buinicky Dickinson College Sarah Rachel Burger Dickinson College Blair Hetherington Douglas Dickinson College Michelle Erika Garman Dickinson College Danielle Marie Gower Dickinson College See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_work Part of the Contemporary Art Commons Recommended Citation Hirsh, Sharon, et al. Woodcuts to Wrapping Paper: Concepts of Originality in Contemporary Prints. Carlisle, Pa.: The rT out Gallery, Dickinson College, 2005. This Exhibition Catalog is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship & Creative Works at Dickinson Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in Student Scholarship & Creative Works By Year by an authorized administrator of Dickinson Scholar. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Authors Alison Buinicky, Sarah Rachel Burger, Blair Hetherington Douglas, Michelle Erika Garman, Danielle Marie Gower, Blair Lesley Harris, Laura Delong Heffelfinger, Saman Mohammad Khan, Ryan McNally, Erin Elizabeth Mounts, Nora Marisa Mueller, Alexandra Thayer, Heather Jean Tilton, Sharon L. Hirsh, and Trout Gallery This exhibition catalog is available at Dickinson Scholar: http://scholar.dickinson.edu/student_work/9 WOODCUTS TO Concepts of Originality in Contemporary Wrapping Paper Prints WOODCUTS TO Concepts of Originality in Contemporary Wrapping Paper Prints January 28 – March 5, 2005 Curated by: Alison Buinicky Sarah Burger Blair H. Douglas Michelle E. Garman Danielle M. Gower Blair L. Harris Laura D. Heffelfinger Saman Khan Ryan McNally Erin E. Mounts Nora M. -

Karin Broker

KARIN BROKER 1950 Born in Penn, Pennsylvania EDUCATION 1972 BFA, University of Iowa 1973 Atelier 17, Paris, France (Fall) 1980 MFA, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1980 Professor at Rice University 2003 Chair of Department of Visual Arts HONORS, AWARDS AND GRANTS 2010 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University 2008 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University 2003 Who’s Who in American Art. 25th. Edition 2002 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University Jerome J. Segal Grant. Rice University 1997 Brown Teaching Grant. Rice University 1996 Julia Mile Chance Teaching Prize. Rice University 1994 Texas Artist of the Year. Art League of Houston 1993 Cultural Arts Council of Houston Grant 1992 Best Local Artist. Houston Press. 1989 Mellon Fellowship Dewar's Texas Doers (50 Texans) 1985 National Endowment for the Arts Grant 1987 National Endowment for the Arts Grant SOLO EXHIBITIONS 2018 love me, love me not, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2014 more damn girls, UT Tyler Meadows Gallery, Tyler, Texas Karin Broker: wired, drawn and nailed, Art Museum of Southeast Texas, Beaumont, Texas damn girls, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2013 Trouble in Paradise, Kirk Hopper Fine Arts Gallery, Dallas, Texas 2012 Karin Broker: Wired, Nailed, Drawn and Printed, Galveston Arts Center, Galveston, Texas 2010 Oddities and Other Opinions, McClain Gallery, Houston, Texas 2006 Mad Girl. McClain Gallery. Houston, Texas 2005 A Mad Girl’s Small Notes. McClain Gallery. Houston, Texas 2003 Dark Talk. McClain Gallery. Houston, Texas 2000 Domestic Melancholia. Merwin and Wakeley Galleries. Illinois Wesleyan University. Bloomington, Illinois Karin Broker….Drawing in sanguine. Gerhard Wurzer Gallery. Houston, Texas 1997 Etchings. Augen Gallery. Portland, Oregon 1996 Notes of a mad girl. -

In the Studio

Wendell H. Black 17. Picasso at Mougins: The Etchings, 2002 Erik Desmazières 29. With Aldo Behind Me, 2008 62. Copyists at the Metropolitan Museum, 1908 CHECKLIST (American, 1919–1972) Soft-ground etching, aquatint, sugar-lift (French, born 1948) Aquatint, etching, drypoint, and mechanical Etching; unnumbered edition of 100 1 Dimensions are in inches; 6. Artist and Model—Spring II, 1958 aquatint, with à la poupée inking and relief 25. Atelier René Tazé IV, 1992 abrasion; edition 12/15 plate: 7 /2 x 9 IN THE STUDIO 1 1 1 Woodcut; edition 11/25 rolls through stencils; edition 91/200 Etching, aquatint and roulette; plate: 46 /2 x 38 /2 sheet: 11 x 13 /8 1 5 7 5 3 height precedes width. image: 23 /8 x 38 plate: 17 /8 x 23 /8 edition 16/75 sheet: 54 /8 x 46 /8 Courtesy of Davidson Galleries, Seattle, and 5 7 7 sheet: 28 x 41 sheet: 23 /8 x 30 plate: 25 /8 x 19 /8 Courtesy of Augen Gallery Kraushaar Galleries, New York Reflections on Artistic Life 1 Museum Purchase The Carol and Seymour Haber Collection sheet: 30 x 22 /4 Edward Ardizzone 30. Snips, Pliers, and Hammers, 2011 Raphael Soyer (British, 1900–1979) 92.217.44 2004.33.5 Museum Purchase: Hank and Judy Hummelt Fund Woodcut and etching; edition 12/15 (American, 1899–1987) 1. The Model, 1953 1 FEBRUARy 2 – MAy 19, 2013 Frank Boyden Charles‑François Daubigny 1995.18.1 plate: 48 x 38 /4 63. Young Model, 1940 5 1 Lithograph; edition 29/30 (American, born 1942) (French, 1817–1878) sheet: 50 /8 x 40 /8 Lithograph; unnumbered edition of 250 1 5 8 8 3 image: 8 / x 10 / 7. -

On Collecting (Part One) • Prints and Posters in the Fin

US $25 The Global Journal of Prints and Ideas May – June 2017 Volume 7, Number 1 On Collecting (Part One) • Prints and Posters in the Fin de Siècle • An Artist Collects • eBay as Archive Norman Ackroyd • Collecting for the Common Good • Hercules Segers • Prix de Print • Directory 2017 • News Art_in_Print_8.25x10.75_ExpoChicago 4/24/17 12:55 PM Page 1 13–17 SEPTEMBER 2017 CHICAGO | NAVY PIER Presenting Sponsor Opening EXPO ART WEEK by Lincoln Schatz Lincoln by Series Lake (Lake Michigan) (Lake Off-site Exhibition 16 Sept – 7 Jan 2018 12 Sept – 29 Oct 2017 expochicago.com May – June 2017 In This Issue Volume 7, Number 1 Editor-in-Chief Susan Tallman 2 Susan Tallman On Collecting (Part One) Associate Publisher Fleur Roos Rosa de Carvalho 3 Julie Bernatz Interviewed by Catherine Bindman Small Apartments and Big Dreams: Managing Editor Print Collecting in the Fin de Siècle Isabella Kendrick Jillian Kruse 7 Associate Editor Postermania: Advertising, Domesticated Julie Warchol Brian D. Cohen 11 An Artist Collects Manuscript Editor Prudence Crowther Jennifer S. Pride 14 Secrets of the Real Thing: Building a Editor-at-Large Collection as a Graduate Student Catherine Bindman Kay Wilson and Lesley Wright 18 Design Director Speak with Sarah Kirk Hanley Skip Langer To Serve the Common Good: The Grinnell College Art Collection Roslyn Bakst Goldman and 24 John L. Goldman A Socially Acceptable Form of Addiction Kit Smyth Basquin 26 Collecting a Life Patricia Emison 28 Norman Ackroyd’s Collectors Stephen Snoddy Speaks 32 with Harry Laughland Collecting in the Midlands: the New Art Gallery Walsall Prix de Print, No. -

Acrylic on Canvas Colescott Was Born in Oakland, California in 1925. This Painting Celebrates the Pioneering Spirit of Colescott

1919, 1980 Acrylic on canvas Courtesy of the Estate and Blum & Poe, Los Angeles/New York/ Tokyo, L2019.104.3 Colescott was born in Oakland, California in 1925. This painting celebrates the pioneering spirit of Colescott’s parents, Lydia Hutton Colescott and Warrington Colescott, Sr. Following the famous exhortation of John Babsone Lane Soule (widely attributed to publisher Horace Greeley) in the mid-nineteenth century to “Go West,” Colescott’s parents moved from New Orleans to Oakland in 1919. Colescott evokes nineteenth-century silhouette traditions in the bust-length profile depictions of his parents, who are nestled in pink clouds facing each other across the composition. He has dispersed various elements—a tipi, a moose, a house, spotted mustang, a cowboy, an oil well, a goat, and mountain ranges—throughout a multicolored map of the United States. In the center, a large tree in a cut away space supports the nest of two birds, representing Colescott’s parents, who tend to two chicks, which represent the artist and his older brother Warrington, Jr. The garbage that litters the clouds represents what Colescott described in 1981 as the “used underwear, popular trash, studio sweepings…that didn’t pass art history.” Untitled, 1949 Oil on canvas Collection of Lauren McIntosh, Berkeley, CA, L2019.104.46 This work—never before exhibited in public—is in the collection of Colescott’s cousin Lauren McIntosh, who was given it by the artist. It indicates his style of painting when he was working on his graduate degree at Berkeley. What is striking is the interplay of rectangular and trapezoidal planes, which predicate how he organized his compositions later in his career despite their more figurative orientation. -

PDF Released for Review Purposes Only Not for Publication Or Wide

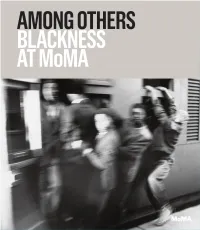

only purposes distribution reviewwide for or released publication PDF for Not only purposes distribution reviewwide for or released publication PDF for Not AMONG OTHERS Darby English and Charlotte Barat BLACKNESS AT MoMA The Museum of Modern Art, New York CONTENTS BLACKNESS AT MoMA: A LEGACY OF DEFICIT Foreword Glenn D. Lowry onlyCharlotte Barat and Darby English 9 14 → 99 Acknowledgments 11 purposes distribution WHITE reviewwide BY DESIGN for Mabel O. Wilson or 100 → 109 released publication AMONG OTHERS PDF Plates for 111 → 475 Not Contributors 476 Trustees of The Museum of Modern Art 480 Plates Terry Adkins Marcel Broodthaers Melvin Edwards Leslie Hewitt Man Ray John Outterbridge Raymond Saunders James Van Der Zee A Akili Tommasino 112 Christophe Cherix 154 Paulina Pobocha 194 Roxana Marcoci 246 M Quentin Bajac 296 Nomaduma Rosa Masilela 340 Richard J. Powell 394 Kristen Gaylord 438 John Akomfrah Charles Burnett William Eggleston Richard Hunt Robert Mapplethorpe Euzhan Palcy Lasar Segall Melvin Van Peebles Kobena Mercer 114 Dessane Lopez Cassell 156 Matthew Jesse Jackson 196 Samuel R. Delany 248 Tavia Nyong’o 298 P Anne Morra 342 Edith Wolfe 396 Anne Morra 440 Njideka Akunyili Crosby Elizabeth Catlett Minnie Evans Hector Hyppolite Kerry James Marshall Gordon Parks Ousmane Sembène Kara Walker Christian Rattemeyer 116 C Anne Umland 158 Samantha Friedman 198 J. Michael Dash 250 Laura Hoptman 300 Dawoud Bey 344 Samba Gadjigo 398 W Yasmil Raymond 442 Emma Amos Nick Cave Fred Eversley Arthur Jafa Rodney McMillian Benjamin Patterson Richard Serra Jeff Wall Christina Sharpe 118 Margaret Aldredge-Diamond 160 Cara Manes 200 J Claudrena N. -

Celebrating New Work, New Artists, New Processes and New Collectors

Celebrating new work, new artists, new processes and new collectors Founded in 1915 The Print Center supports printmaking and photography as vital contemporary arts and encourages the appreciation of the printed image in all its forms. September 8 - November 9, 2005 Gala and Tour by John Ittmann, Curator of Prints Philadelphia Museum of Art Thursday, September 8, 2005 5:00 - 7:00 p.m. Introduction Reflectingt over The Print Center’s 90 years history I feel very grateful for the many thousands of members and supporters, who have secured not only the longevity of the organization but it’s ongoing vitality. We are grateful for the support of the many artists, collectors and enthusiasts who have helped to make The Print Center what it is today, a national and international nexus for primakers, photographers and collectors which pur- sues work at the cutting edges of technique and at the highest level of the art form. At 90, The Print Center is a dynamic institution supporting prints and photographs and encouraging the appreciation of the printed image in all its forms. Encouraging new artists, new work, new processes and new collectors this visionary mission crossing two disciplines has provided a platform to showcase and educate in the latest developments in both of these media. But we never forget our roots and support all the traditional and older processes in conjunction with these modern advances. With the current rise in digital tools for both media, it has stimulated a renaissance in both older methods, and the mixing of these with the latest computer tools. -

Winter 2005 President’S Greeting Recent Club Events Julian Hyman

The Print Club of New York Inc Winter 2005 President’s Greeting Recent Club Events Julian Hyman ur Print Club began 2005 with an exceptional event at The New-York Historical Society. The O show consisted of a display of prints of New York City from the seventeenth century up through and including prints from the year 2004. It was satisfying to see a number of artists represented who have participated over the years in our Artists Showcase. The exhibit will remain at the Historical Society through March. I have had exceptionally good feedback about our recent Presentation Print by Ed Colker. The difficult deci- sion of choosing the artist for the annual Presentation Print remains with the Print Selection Committee. Each year, the composition of the committee changes with the addition of at least two new members. In addition, the Chairperson — chosen from the committee — rotates PHOTO BY GILLIAN HANNUM annually. We are updating our method of distribution of Charlotte Yudis and Bill Murphy the print and hope to eliminate a problem that has delayed the mailing to some of our members. I am pleased to say that we have added a number of Eleventh Annual Artists’ Showcase younger members recently and feel that this is very good news for the Club, which is in its thirteenth year of opera- Gillian Greenhill Hannum tion. The prestigious Fogg Museum at Harvard University has indicated a desire to add a number of our n October 19, 2004, Print Club members and their Presentation Prints to its collection. Prints published by guests assembled at the National Arts Club on The Print Club of New York are now in many museums O Gramercy Square for the Eleventh Annual in the United States, Great Britain and Scotland. -

2010 Annual Report

10 annual report 2010 annual report 2010 annual report 6 Board of Trustees 9 President and Chairman’s Report 10 Director’s Report 12 2010 Breakdown 14 Curatorial Report 17 Exhibitions 20 Publications 23 Loans 27 Acquisitions 3 5 Education and Public Programs 36 Development 40 Donors 54 Docents and Volunteers 57 Staff 60 Financial Report cover Ted Croner, Times Square Montage, 1947 (detail). Purchase, Leonard and Bebe LeVine Art Acquisition Fund. Full credit listing on p. 30. left David Lenz, Sam and the Perfect World, 2005 (detail). Purchase, with funds from the Linda and Daniel Bader Foundation, Suzanne and Richard Pieper, and Barbara Stein. Full credit listing on p. 27. Unless otherwise noted, all photographs of works in the Collection are by John R. Glembin. 6 | board of trustees Through August 31, 2010 BOARD OF TRUSTEES Mary M. Strohmaier Anthony J. Petullo Photography Committee W. Kent Velde Christine Symchych Richard R. Pieper Kevin Miyazaki Chairman Stacy G. Terris Sandra Robinson Chair Raymond R. Krueger Frederick Vogel IV Reva Shovers Carol Lewensohn Beth R. Wnuk Christine Symchych President Vice Chair Jeffery W. Yabuki Frederick Vogel III Betty Ewens Quadracci Andrew A. Ziegler Robert A. Wagner Warren Blumenthal Secretary Barbara Ciurej Danny L. Cunningham COMMITTEES OF THE ACQuisitioNS AND George A. Evans, Jr. BOARD OF TRUSTEES CollectioNS Committee Treasurer F. William Haberman Subcommittees Lindsay Lochman Frederic G. Friedman EXecutiVE Committee Decorative Arts Madeleine Lubar Assistant Secretary and Raymond R. Krueger Committee Marianne Lubar Chair Legal Counsel Constance Godfrey Cardi Smith Christopher S. Abele Members at LarGE Chair Christine Symchych Donald W. -

Frances Myers Department of Art University of Wisconsin-Madison [email protected]

Frances Myers Department of Art University of Wisconsin-Madison [email protected] http://www.francesmyers.com BIOGRAPHY: Born, Racine, Wisconsin BS, MS, MFA, University of Wisconsin-Madison (printmaking and painting) Studied, San Francisco Art Institute TEACHING: 1996- Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1990-96 Associate Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1988-89 Assistant Professor, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1986-88 1983-84, 1980-82, Lecturer, University of Wisconsin-Madison 1982 Lecturer, University of California-Berkeley 1979 Distinguished Professor of Art, Lucie Stern Chair, Mills College, Oakland, California 1974-75 St. Martin’s School of Art, London, England 1974-75 Birmingham College of Art and Design, Birmingham. England HONORS AND GRANTS: 2007 Research Grant, UW Graduate School, Research Assistant 2006 Graduate School Grant for Travel Abroad 2006 Sabbatical (semester research Leave) 2000 Research Grant, Univ. of Wisconsin Graduate School (semester research leave) 1999 Kellett Mid-Career Award, Univ. of Wisconsin Graduate School 1999 Sabbatical (semester research leave) 1998 Professional Dimensions, Milwaukee, Wisconsin, the Sacajawea Award Commission Artist 1997-98 Vilas Associates Fellow, Graduate School Award, Univ. of Wisconsin/Madison 1995 Faculty Development Grant, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Semester I 1995 Graduate School Research Grant, University of Wisconsin-Madison, summer salary/equipment 1994 Elected Full Member (Academician): National Academy ofArt, New York City 1994 Graduate School Research Grant, University of Wisconsin-Madison, summer research 1994 Invited to apply for the Dodd Chaired Professorship, University of Georgia-Athens 1993 Elected Associate Member: National Academy of Design, New York City 1993 Graduate School Research Grant, University of Wisconsin-Madison (travel, equipment) 1991 H.I.