The Undersigned, Appointed by the Dean of the Graduate School, Have Examined the Dissertation Entitled

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Patterns of Behavior: Analyzing Modes of Social Interaction from Prehistory to the Present

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work 5-2010 Patterns of Behavior: Analyzing Modes of Social Interaction from Prehistory to the Present Whitney Nicole Hayden University of Tennessee - Knoxville, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Part of the Other Languages, Societies, and Cultures Commons Recommended Citation Hayden, Whitney Nicole, "Patterns of Behavior: Analyzing Modes of Social Interaction from Prehistory to the Present" (2010). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1374 This Dissertation/Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Patterns of BEHAVIOR APPROPRIATE INTERACTION IN SOCIETY: FROM PREHISTORY TO THE PRESENT Patterns of BEHAVIOR APPROPRIATE INTERACTION IN SOCIETY: FROM PREHISTORY TO THE PRESENT We are spending less time with physical people and the community and more time with objects. We are getting to the point where we don’t have to interact with people in the physical: e-mail, instant messaging, texting, tweeting, and social networking. Are we having real conversations? There is no intonation in an e-mail or text message. Doesn’t intonation, body language, and facial expressions make up half of the experience in a conversation? Merriam-Webster defines “conversation” as such: oral exchange of Western civilization has been captivated by the electronic sentiments, observations, opinions, or ideas. -

Beauties of the Gilded Age: Peter Marié's Miniatures of Society Women

BEAUTIES OF THE GILDED AGE: PETER MARIÉ'S MINIATURES OF SOCIETY WOMEN Clausen Coope (1876-after 1940), Miss Maude Adams (1872- 1953), 1902. New-York Historical Society, Gift of the Estate of Peter Marié, 1905.1 Legendary stage actress Maude Adams made her Broadway debut in 1888 and achieved greatest acclaim in the role of Peter Pan. As the “Boy Who Wouldn’t Grow Up,” she appeared in more than 1,500 performances and earned an astronomical $20,000 a month. Adams was rarely seen in public outside the theatre, and it is unlikely that Peter Marié knew her personally. He probably commissioned this miniature from a publicity photograph. Meave Thompson Gedney (1863-1905), Mrs. William Waldorf Astor (Mary Dahlgren Paul, 1856-1894), ca. 1890. New-York Historical Society, Gift of the Estate of Peter Marié, 1905.10 A native of Philadelphia, Mary Paul married New Yorker William Waldorf Astor in 1878. In 1882, the Astors moved to Rome after William was appointed American minister to Italy, and they established a residence in England in 1890. Mrs. Astor became a society leader in New York, Rome, and London. She shared her married name with her husband’s aunt and social rival, Mrs. William (Caroline) Astor, the undisputed queen of New York society. Caroline Astor boldly claimed the title of the Mrs. Astor. Fernand Paillet (1850-1918), Mrs. Grover Cleveland (Frances C. Folsom, 1864-1947), 1891. New-York Historical Society, Gift of the Estate of Peter Marié, 1905.44 Frances Folsom of Buffalo, New York, married President Grover Cleveland at the White House on June 2, 1886. -

Electronic Press Kit for Laura Claridge

Electronic press kit for Laura Claridge Contact Literary Agent Carol Mann Carol Mann Agency 55 Fifth Avenue New York, NY 10003 • Tel: 212 206-5635 • Fax: 212 675-4809 1 Personal Representation Dennis Oppenheimer • [email protected] • 917 650-4575 Speaking engagements / general contact • [email protected] Biography Laura Claridge has written books ranging from feminist theory to bi- ography and popular culture, most recently the story of an Ameri- can icon, Emily Post: Daughter of the Gilded Age, Mistress of Amer- ican Manners (Random House), for which she received a National Endowment for the Humanities grant. This project also received the J. Anthony Lukas Prize for a Work in Progress, administered by the Nieman Foundation for Journalism at Harvard and the Columbia University Graduate School of Journalism. Born in Clearwater, Florida, Laura Claridge received her Ph.D. in British Romanticism and Literary Theory from the University of Mary- land in 1986. She taught in the English departments at Converse and Wofford colleges in Spartanburg, SC, and was a tenured professor of English at the U.S. Naval Academy in Annapolis until 1997. She has been a frequent writer and reviewer for the national press, appearing in such newspapers and magazines as The Wall Street Journal, Vogue, The Boston Globe, Los Angeles Times, and the Christian Science Monitor. Her books have been translated into Spanish, German, and Polish. She has appeared frequently in the national media, including NBC, CNN, BBC, CSPAN, and NPR and such widely watched programs as the Today Show. Laura Claridge’s biography of iconic publisher Blanche Knopf, The Lady with the Borzoi, will be published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux in April, 2016. -

Lesson Seven: Cyberbullying Background Discussion Questions

Lesson Seven: Cyberbullying Background Cyberbullying is a new dimension to the age-old bullying issue complicated by access to Internet communication by all ages. Experts agree, the methods of cyberbullying are limited only by the child's imagination and access to technology. And the cyberbully one moment may become the victim the next. The kids often change roles, going from victim to bully and back again. Experts also acknowledge that cyberbullying can take place off-campus and outside of school hours, often limiting school involvement, which makes education, awareness and self- responsibility particularly important. Discussion Questions 1. In your opinion, how do most kids your age hurt each other? 2. Is bullying common in your school? Explain your answer. 3. Alison Goller says, “People at the school feel…everybody gets made fun of.” Is that your experience? Explain. 4. Have you experienced cyberbullying? Describe the experience. 5. If you have experienced cyberbullying, did you tell your parents? Why or why not? Do you think this is typical for kids your age? Why? 6. Mr. Halligan says, “The middle school environment…is very toxic.” Think about your middle school years. Do you agree or disagree? Why? Vocabulary Builders Term Definition Bullying A term used to describe the act of using threats or fear (e.g., physical harm) to get another person to do something against their will. When a child, preteen or teen is tormented, threatened, harassed, Cyberbullying humiliated, embarrassed or otherwise targeted by another child, preteen or teen using the Internet, interactive and digital technologies or mobile phones. Refers to a suicide attributable to the victim having been bullied either in Bullycide person or via social media. -

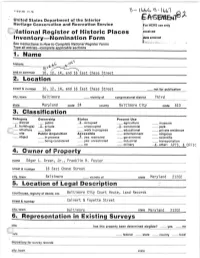

National Register of Historic Places Inventory—Nomination Form 1

B-1666 & B-1667 F"B-*-300 (11-78) I- United. States Department of the Interior Heritage Conservation and Recreation Service For HCRS use only I National Register of Historic Places received Inventory—Nomination Form date entered See instructions in How to Complete National Register Forms Type all entries—complete applicable sections 1. Name historic , feC ^ and or common io, 12, 14, and 16 East Chase Street 2. Location street & number 10, 12, 14, and 16 East Chase Street _ not for publication city, town Baltimore vicinity of congressional district Third state Maryland code 24 county Baltimore City code 510 3. Classification Category Ownership Status Present Use district public X occupied agriculture museum X building(s) X private unoccupied X commercial park — structure both work in progress educational private residence site Public Acquisition Accessible entertainment religious object in process X yes: restricted government scientific being considered yes: unrestricted industrial transportation no . military other: APTS. & OFFIC 4. Owner of Property name Edgar L. Green, Jr., Franklin R. Foster street & number 16 East Chase Street city, town Baltimore vicinity of state Maryland 21202 5. Location of Legal Description courthouse, registry of deeds, etc. Baltimore City Court House, Land Records street & number Calvert & Fayette Street city, town Baltimore state Maryland 21202 6. Representation in Existing Surveys title has this property been determined elegible? yes no Jate federal state county local depository for survey records city, town state 7. Description B-1666 & B-1667 Condition Check one Check one excellent deteriorated unaltered X original site x good ruins x altered moved date fair unexposed (interior only) Describe the present and original (if known) physical appearance 10 East Chase Street This 3%-story brick townhouse, laid in common bond, has a three-bay front facade and is fitted with marble facing from ground to first floor level. -

![Jgukx.Ebook] Etiquette Pdf Free](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/3022/jgukx-ebook-etiquette-pdf-free-4733022.webp)

Jgukx.Ebook] Etiquette Pdf Free

JgUkx (Ebook pdf) Etiquette Online [JgUkx.ebook] Etiquette Pdf Free Emily Post ePub | *DOC | audiobook | ebooks | Download PDF Download Now Free Download Here Download eBook #5470208 in Books 2015-05-08Original language:EnglishPDF # 1 11.00 x .52 x 8.50l, 1.20 #File Name: 1512111082228 pages | File size: 78.Mb Emily Post : Etiquette before purchasing it in order to gage whether or not it would be worth my time, and all praised Etiquette: 0 of 0 people found the following review helpful. Promotes Kindness, Politeness, and Appropriateness as a LifestyleBy Jennifer CalderoneThis book promotes kindness, politeness, and appropriateness as a lifestyle. The situations, of course, are entirely outmoded -- almost 100 years old -- but an intelligent reader can read between the lines to discern the appropriate, polite, and kind way to behave in contemporary situations. Simply because of my own interests, I particularly like Mrs. Post's observations on style and dress; her comments about fashion are spot-on, even for the 21st century. Because of changes in dress over the course of the 20th century, her list of clothing appropriate for a well-bred man can be used even for a contemporary woman to build her own wardrobe -- with reading between the lines and discernment, of course.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. Some kind of joke? Selling a book with blank pages?By CustomerNo stars. This book sold to me has blank pages throughout. Buyer beware. It's too late for me to return it unfortunately, and I am stuck with a book full of blank pages.1 of 1 people found the following review helpful. -

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions by Ned Hémard

NEW ORLEANS NOSTALGIA Remembering New Orleans History, Culture and Traditions By Ned Hémard When to Wear White So many inquiring readers wish to know the history and psychology of when it is appropriate to wear white, especially in New Orleans. The presumably hard-and-fast rule (although it has been broken by some noteworthy characters) is from Easter until Labor Day. Now, this refers to white suits and white bucks on men, as well as white outfits, pumps and dress shoes on women. Exempt are tennis shoes and any gown or shoes worn by a winter bride. That’s the consensus in the Crescent City and most of the South. But some etiquette authorities say the traditional guideline of when to wear white is only between Memorial Day and Labor Day. David A. Bagwell, a lawyer and former U.S. magistrate from Mobile, has written his view on this, stating, “My answer to them is that they have gradually become – apparently unknowingly, I’ll charitably grant them that – the pawns and tools of the general Yankee-fication of America.” His research confirms that in general, over the South, Easter weekend – and not Memorial Day - was the beginning” since “Easter was the day on which boys got a new white linen coat, if their parents could afford one”. For “white shoes” it was the same. “They didn’t wait until Memorial Day,” he asserted. Also, Memorial Day (formerly known as Decoration Day) was first enacted to honor Union soldiers of the American Civil War. Celebrated on the last Monday of May, it wasn’t until after World War I that it was extended to honor those Americans who have died in all wars. -

Tuxedo Park Library to Harvard Business School, the Artists’ Retreat Yaddo, the Juilliard School, Dartmouth Library, and More

T uxedo PARK Lives, Legacies, Legends Chiu Yin Hempel Foreword by Francis Morrone Book Description COPYRIGHTED MATERIAL Tuxedo park Lives, Legacies, Legends Tuxedo Park, one of America’s first planned communities, was for decades synonymous with upper-class living. An exclusive gentleman’s club founded here in 1886 had among its early members the Vanderbilts, Astors, and Morgans. The tuxedo jacket had its debut in America in this Hudson Valley enclave. Well known for the period houses that were designed by the most renowned architects of the late 19th and early 20th centuries, it is a historical community deemed worthy of preservation by the National Register of Historic Places. But more importantly, Tuxedo was home to generations of immigrants – both rich and poor – whose deeds shaped America’s culture, society, and economy at the turn of the 20th century. Indeed, it was the extraordinary legacies of these early residents that earned Tuxedo approbation in history. Women’s rights in America were first asserted here by courageous pioneers such as Cora Urquhart, Maude Lorillard, Eloise Breese, Susan Tuckerman, and Adele Colgate; proper manners were encoded by Emily Post; and the look of a century was defined by Dorothy Draper. It was here that a farm boy, whose father worked as an undertaker, founded Orange & Rockland Utilities, while two well-born men came to financial ruin by pursuing a lifestyle of Gilded Age excess. It was a Tuxedo resident who funded Thomas Edison’s inventions, and another who donated antique furniture that formed the cornerstone of the American Wing collection in the Metropolitan Museum of Art. -

ON SAFARI with Sara Exploring Tanzania

August & September 2018 No. 76 H V N N J ON SAFARI with Sara Exploring Tanzania Teddy Roosevelt • 1939 World’s Fair • Emily Post Hudson Valley’s Underground Railroad GARY GOLDBERG FINANCIAL SERVICES MONEY MANAGEMENT FOR REAL PEOPLE www.ggfs.com • 800-433-0323 • 75 Montebello Road, Suffern, NY 10901 ABOUT GARY GOLDBERG FINANCIAL SERVICES Founded in 1972, Gary Goldberg Financial Services has been serving individual investors for four generations. We bring a unique blend of knowledge, experience, and resources to every client relationship that we serve, offering the highest caliber of service from a team of nationally recognized experts. At Gary Goldberg Financial Services, we believe managing clients’ assets is a long- term proposition. In fact, many of our client relationships span generations. We’ll work diligently to develop a customized wealth and investment strategy for you that incorporates investment management & legacy planning designed to help you achieve all of your investment and life goals. We have helped thousands of investors achieve their retirement goals. Our investment process is designed and implemented by our Strategic Investment Committee, whose members have over 137 years of combined experience amongst GARY M. GOLDBERG is the founder and CEO of Gary Goldberg Financial them. Services which he started in 1972. He has built Gary Goldberg Financial Services into one of the premier full-service For more information about Gary Goldberg Financial Services visit investment management firms providing www.ggfs.com or call 1-800-433-0323. Money Management for Real People and helping thousands of investors achieve their retirement goals. You’ve worked hard to save for your retirement. -

Emily Post’ S Etiquette (1922 – 2011)

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by University of Hertfordshire Research Archive 1 0 Small Change? Emily Post ’ s Etiquette (1922 – 2011) Dr Grace Lees-Maffei In the contemporary book market, nonfiction genres such as biography and self-help command considerable sales, 1 yet “ bestseller ” is still a term primarily associated with fiction (the nature of that fiction is explored in this book). 2 This chapter examines a nonfiction text which has been a bestseller for nine decades, and the pre-eminent example of American advice literature, Emily Post ’ s Etiquette . In catering to the social needs and aspirations of its readers, Etiquette has described as well as prescribed US social interaction and is, therefore, a useful tool in calibrating the changing nature of the American dream. Succeeding members of the Post family have renewed the book ’ s content and thereby ensured its continued popularity. By examining these processes of change — of authorship and content — this chapter shows how nonfiction bestsellers maintain and rejuvenate their markets in a manner quite distinct from the majority of bestsellers which are relatively unchanging works of fiction, bound up with their original authors. Etiquette , self-help, and America Collectively, the successive editions of Etiquette 3 form perhaps the best-known American example of the group of etiquette and MMustust RRead.indbead.indb 221717 55/17/2012/17/2012 11:03:27:03:27 PPMM 218 MUST READ: REDISCOVERING AMERICAN BESTSELLERS manners guides, which can be understood as a small sub-section of a larger cultural category, self-help, which is in turn a highly commercially successful strand of the nonfiction market, along with lifestyle genres including cookbooks, biography and reference titles, and textbooks on a range of subjects. -

“If Music Be the Food of Love, Play On

When to Wear White So many inquiring readers wish to know the history and psychology of when it is appropriate to wear white, especially in New Orleans. The presumably hard-and-fast rule (although it has been broken by some noteworthy characters) is from Easter until Labor Day. Now, this refers to white suits and white bucks on men, as well as white outfits, pumps and dress shoes on women. Exempt are tennis shoes and any gown or shoes worn by a winter bride. That’s the consensus in the Crescent City and most of the South. But some etiquette authorities say the traditional guideline of when to wear white is only between Memorial Day and Labor Day. Throngs turn out in August for Whitney White Linen Night. David A. Bagwell, a lawyer and former U.S. magistrate from Mobile, has written his view on this, stating, “My answer to them is that they have gradually become – apparently unknowingly, I’ll charitably grant them that – the pawns and tools of the general Yankee-fication of America.” His research confirms that in general, over the South, Easter weekend – and not Memorial Day - was the beginning” since “Easter was the day on which boys got a new white linen coat, if their parents could afford one”. For “white shoes” it was the same. “They didn’t wait until Memorial Day,” he asserted. Also, Memorial Day (formerly known as Decoration Day) was first enacted to honor Union soldiers of the American Civil War. Celebrated on the last Monday of May, it wasn’t until after World War I that it was extended to honor those Americans who have died in all wars.