Preface and Acknowledgments

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Shostakovich (1906-1975)

RUSSIAN, SOVIET & POST-SOVIET SYMPHONIES A Discography of CDs and LPs Prepared by Michael Herman Dmitri Shostakovich (1906-1975) Born in St. Petersburg. He entered the Petrograd Conservatory at age 13 and studied piano with Leonid Nikolayev and composition with Maximilian Steinberg. His graduation piece, the Symphony No. 1, gave him immediate fame and from there he went on to become the greatest composer during the Soviet Era of Russian history despite serious problems with the political and cultural authorities. He also concertized as a pianist and taught at the Moscow Conservatory. He was a prolific composer whose compositions covered almost all genres from operas, ballets and film scores to works for solo instruments and voice. Symphony No. 1 in F minor, Op. 10 (1923-5) Yuri Ahronovich/Moscow Radio Symphony Orchestra ( + Overture on Russian and Kirghiz Folk Themes) MELODIYA SM 02581-2/MELODIYA ANGEL SR-40192 (1972) (LP) Karel Ancerl/Czech Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphony No. 5) SUPRAPHON ANCERL EDITION SU 36992 (2005) (original LP release: SUPRAPHON SUAST 50576) (1964) Vladimir Ashkenazy/Royal Philharmonic Orchestra ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15, Festive Overture, October, The Song of the Forest, 5 Fragments, Funeral-Triumphal Prelude, Novorossiisk Chimes: Excerpts and Chamber Symphony, Op. 110a) DECCA 4758748-2 (12 CDs) (2007) (original CD release: DECCA 425609-2) (1990) Rudolf Barshai/Cologne West German Radio Symphony Orchestra (rec. 1994) ( + Symphonies Nos. 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14 and 15) BRILLIANT CLASSICS 6324 (11 CDs) (2003) Rudolf Barshai/Vancouver Symphony Orchestra ( + Symphony No. -

Link Shostakovich.Txt

FRAMMENTI DELL'OPERA "TESTIMONIANZA" DI VOLKOV: http://www.francescomariacolombo.com/index.php?option=com_content&view=article&i d=54&Itemid=65&lang=it LA BIOGRAFIA DEL MUSICISTA DA "SOSTAKOVIC" DI FRANCO PULCINI: http://books.google.it/books?id=2vim5XnmcDUC&pg=PA40&lpg=PA40&dq=testimonianza+v olkov&source=bl&ots=iq2gzJOa7_&sig=3Y_drOErxYxehd6cjNO7R6ThVFM&hl=it&sa=X&ei=yUi SUbVkzMQ9t9mA2A0&ved=0CDEQ6AEwAQ#v=onepage&q=testimonianza%20volkov&f=false LA PASSIONE PER IL CALCIO http://www.storiedicalcio.altervista.org/calcio_sostakovic.html CENNI SULLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.52composers.com/shostakovich.html PERSONALITA' DEL MUSICISTA NELL'APPOSITO PARAGRAFO "PERSONALITY" : http://www.classiccat.net/shostakovich_d/biography.php SCHEMA MOLTO SINTETICO DELLA BIOGRAFIA: http://www.thefamouspeople.com/profiles/dmitry-shostakovich-344.php La mia droga si chiama Caterina La mia droga si chiama Caterina “Io mi aggiro tra gli uomini come fossero frammenti di uomini” (Nietzsche) In un articolo del 1932 sulla rivista “Sovetskoe iskusstvo”, Sostakovic dichiarava il proprio amore per Katerina Lvovna Izmajlova, la protagonista dell’opera che egli stava scrivendo da oltre venti mesi, e che vedrà la luce al Teatro Malyi di Leningrado il 22 gennaio 1934. Katerina è una ragazza russa della stessa età del compositore, ventiquattro, venticinque anni (la maturazione artistica di Sostakovic fu, com’è noto, precocissima), “dotata, intelligente e superiore alla media, la quale rovina la propria vita a causa dell’opprimente posizione cui la Russia prerivoluzionaria la assoggetta”. E’ un’omicida, anzi un vero e proprio serial killer al femminile; e tuttavia Sostakovic denuncia quanta simpatia provi per lei. Nelle originarie intenzioni dell’autore, “Una Lady Macbeth del distretto di Mcensk” avrebbe inaugurato una trilogia dedicata alla donna russa, còlta nella sua essenza immutabile attraverso differenti epoche storiche. -

William Kentridge Brings 'Wozzeck' Into the Trenches

William Kentridge Brings ‘Wozzeck’ Into the Trenches The artist’s production of Berg’s brutal opera, updated to World War I, has come to the Metropolitan Opera. By Jason Farago (December 26, 2019) ”Credit...Devin Yalkin for The New York Times Three years ago, on a trip to Johannesburg, I had the chance to watch the artist William Kentridge working on a new production of Alban Berg’s knifelike opera “Wozzeck.” With a troupe of South African performers, Mr. Kentridge blocked out scenes from this bleak tale of a soldier driven to madness and murder — whose setting he was updating to the years around World War I, when it was written, through the hand-drawn animations and low-tech costumes that Metropolitan Opera audiences have seen in his stagings of Berg’s “Lulu” and Shostakovich’s “The Nose.” Some of what I saw in Mr. Kentridge’s studio has survived in “Wozzeck,” which opens at the Met on Friday. But he often works on multiple projects at once, and much of the material instead ended up in “The Head and the Load,” a historical pageant about the impact of World War I in Africa, which New York audiences saw last year at the Park Avenue Armory. Mr. Kentridge’s “Wozzeck” premiered at the Salzburg Festival in 2017. Zachary Woolfe of The New York Times called it “his most elegant and powerful operatic treatment yet.” At the Met, the Swedish baritone Peter Mattei will sing the title role for the first time; Elza van den Heever, like Mr. Kentridge from Johannesburg, plays his common-law wife, Marie; and Yannick Nézet- Séguin, the company’s music director, will conduct. -

Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician's Perspective

The View from an Open Window: Soviet Censorship Policy from a Musician’s Perspective By Danica Wong David Brodbeck, Ph.D. Departments of Music and European Studies Jayne Lewis, Ph.D. Department of English A Thesis Submitted in Partial Completion of the Certification Requirements for the Honors Program of the School of Humanities University of California, Irvine 24 May 2019 i Table of Contents Acknowledgments ii Abstract iii Introduction 1 The Music of Dmitri Shostakovich 9 Lady Macbeth of Mtsensk District 10 The Fifth Symphony 17 The Music of Sergei Prokofiev 23 Alexander Nevsky 24 Zdravitsa 30 Shostakovich, Prokofiev, and The Crisis of 1948 35 Vano Muradeli and The Great Fellowship 35 The Zhdanov Affair 38 Conclusion 41 Bibliography 44 ii Acknowledgements While this world has been marked across time by the silenced and the silencers, there have always been and continue to be the supporters who work to help others achieve their dreams and communicate what they believe to be vital in their own lives. I am fortunate enough have a background and live in a place where my voice can be heard without much opposition, but this thesis could not have been completed without the immeasurable support I received from a variety of individuals and groups. First, I must extend my utmost gratitude to my primary advisor, Dr. David Brodbeck. I did not think that I would be able to find a humanities faculty member so in tune with both history and music, but to my great surprise and delight, I found the perfect advisor for my project. -

The Theory of Eternal Life

THE THEORY OF ETERNAL LIFE by RODNEY COLLIN Life is a lyre, for its tune is death. LXVI Immortal mortals and mortal immortals—one living LXVII the other's death and dead the other's life. For it is death to the breath of life to become liquid, and death LXVIII to this liquid to become solid. But from such solid comes liquid and from such liquid the breath of life. The path up and the path down is one and the same. LXI Identical the beginning and the end... Living and dead LXX are the same, and so awake and asleep, young and old: LXXVIII the former shifted become the latter, and the latter shifted the former. For time is a child playing draughts, and that child's LXXIX is the move. HERACLEITUS: On the Universe To him who, purified, would break this vicious round And breathe once more the air of heaven—greeting! There in the courts of hades wilt thou find Leftward a beckoning cypress, tall and bright, From out whose root doth flow the water of Oblivion. Approach it not: guard thou thy thirst awhile. For on the other hand—and further—wells From bottomless pool the limpid stream of Memory, Cool, full of refreshment. To its guardians cry thus: ' I am the child of earth and starry sky: Know that I too am heavenly—but parched! I perish: give then and quickly that clear draught Of ice-cold Memory!' And from that fountainhead divine Straightway they'll give thee drink; quaffing the which Thou with the other heroes eternally shalt rule. -

Download Booklet

552129-30bk VBO Shostakovich 10/2/06 4:51 PM Page 8 CD1 1 Festive Overture in A, Op. 96 . 5:59 2 String Quartet No. 8 in C minor, Op. 110 III. Allegretto . 4:10 3 Piano Trio No. 2 in E minor, Op. 67 III. Largo . 5:35 4 Cello Concerto No. 1 in E flat, Op. 107 I. Allegretto . 6:15 5–6 24 Preludes and Fugues – piano, Op.87 Prelude and Fugue No. 1 in C major . 6:50 7 Symphony No. 5 in D minor, Op. 47 II. Allegretto . 5:08 8 Cello Sonata, Op. 40 IV. Allegro . 4:30 9 The Golden Age: Ballet Suite, Op. 22a Polka . 1:52 0 String Quartet No. 3 in F, Op. 73 IV. Adagio . 5:27 ! Symphony No. 9 in E flat, Op. 54 III. Presto . 2:48 @ 24 Preludes – piano, Op. 34 Prelude No. 10 in C sharp minor . 2:06 # Violin Concerto No. 1 in A minor, Op. 77 IV. Burlesque . 5:02 $ The Gadfly Suite, Op. 97a Romance . 5:52 % Symphony No. 10 in E minor, Op. 93 II. Allegro . 4:18 Total Timing . 66:43 CD2 1 Jazz Suite No. 2 VI. Waltz 2 . 3:15 2 Piano Concerto No. 1 in C minor, Op. 35 II. Lento . 8:31 3 Symphony No. 7 in C, Op. 60, ‘Leningrad’ II. Moderato . 11:20 4 3 Fantastic Dances, Op. 5 Polka . 1:07 5 Symphony No. 13 in B flat minor, Op. 113, ‘Babi Yar’ II. Humour . 7:36 6 Piano Quintet, Op. 57 III.Scherzo . -

Functional Anatomy of the Soft Palate Applied to Wind Playing

Review Functional Anatomy of the Soft Palate Applied to Wind Playing Alison Evans, MMus, Bronwen Ackermann, PhD, and Tim Driscoll, PhD Wind players must be able to sustain high intraoral pressures in dition occurs because of a structural deformity, such as with order to play their instruments. Prolonged exposure to these high cleft palate. It is also associated with some other speech dis- pressures may lead to the performance-related disorder velopharyn- orders. VPI occurs when the soft palate fails to completely geal insufficiency (VPI). This disorder occurs when the soft palate fails to completely close the air passage between the oral and nasal close the oronasal cavity while attempting to blow air through cavities in the upper respiratory cavity during blowing tasks, this clo- the mouth, resulting in air escaping from the nose.5 Without sure being necessary for optimum performance on a wind instru- a tight air seal, the air passes into the nasal cavity and can ment. VPI is potentially career threatening. Improving music teach- then escape out the nose. This has a disastrous effect on wind ers’ and students’ knowledge of the mechanism of velopharyngeal playing, as the power behind the wind musicians’ sound closure may assist in avoiding potentially catastrophic performance- related disorders arising from dysfunction of the soft palate. In the relies on enough controlled expired air through the mouth. functional anatomy of the soft palate as applied to wind playing, Understandably, this disorder may potentially end the musi- seven muscles of the soft palate involved in the velopharyngeal clo- cian’s career.6 sure mechanism are reviewed. -

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A

The Structure and Movement of Clarinet Playing D.M.A. DOCUMENT Presented in Partial Fulfilment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Musical Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2018 D.M.A. Document Committee: Dr. Caroline A. Hartig, Chair Dr. David Hedgecoth Professor Katherine Borst Jones Dr. Scott McCoy Copyrighted by Sheri Lynn Rolf, M.D. 2018 Abstract The clarinet is a complex instrument that blends wood, metal, and air to create some of the world’s most beautiful sounds. Its most intricate component, however, is the human who is playing it. While the clarinet has 24 tone holes and 17 or 18 keys, the human body has 205 bones, around 700 muscles, and nearly 45 miles of nerves. A seemingly endless number of exercises and etudes are available to improve technique, but almost no one comments on how to best use the body in order to utilize these studies to maximum effect while preventing injury. The purpose of this study is to elucidate the interactions of the clarinet with the body of the person playing it. Emphasis will be placed upon the musculoskeletal system, recognizing that playing the clarinet is an activity that ultimately involves the entire body. Aspects of the skeletal system as they relate to playing the clarinet will be described, beginning with the axial skeleton. The extremities and their musculoskeletal relationships to the clarinet will then be discussed. The muscles responsible for the fine coordinated movements required for successful performance on the clarinet will be described. -

The Man Who Found the Nose'

SPECIAL INTERVIEW The Man who found The Nose’ An Interview with Gennady Nikolayevich Rozhdestvensky By Alan Mercer Born in Moscow on 4 May 1931, (1974-1977 and 1992-1995), and Rozhdestvensky grew up with his the Vienna Symphony (1980-1982). spritely 85 years of age at conductor father Nikolai Anosov Also in the 1970s, Rozhdestvensky the time of our encounter at (1900-1962) and his singer mother worked as music director and con the Paris-based Shostakovich Natalia Rozhdestvenskaya (1900- ductor of the Moscow Chamber ACentre, Gennady Rozhdestvensky’s1997). After graduating from the Music Theatre, where together with demeanour has barely changed from Central Music School at the Mos director Boris Pokrovsky he revived that of the 1960s, when Western con- cow Conservatory as a pianist in Shostakovich’s 1920s opera The Nose. cert-goers were first treated to his the class of L.N. Oborin, he began Rozhdestvensky has focused individualistic podium style, not to studying what was to become his much of his career on music of mention his highly affable manner career vocation under the guidance the twentieth century, including with audiences and orchestras alike. of his father. In 1951, he trained at premieres of works by Shchedrin, As one of the few remaining artists the Bolshoi Theatre, and went on to Slonimsky, Eshpai, Tishchenko, to have worked closely with the 20th work at the famous venue at vari Kancheli, Schnittke, Gubaidulina, century’s music elite—Shostakovich ous periods between 1951 and 2001, and Denisov. included—the conductor’s career is when he became the establishment’s Prior to our conversation, the imbibed with both the traditions General Artistic Director. -

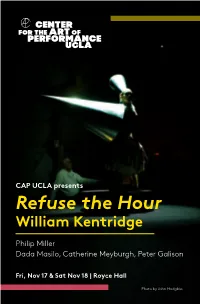

William Kentridge

CAP UCLA presents Refuse the Hour William Kentridge Philip Miller Dada Masilo, Catherine Meyburgh, Peter Galison Fri, Nov 17 & Sat Nov 18 | Royce Hall Photo by John Hodgkiss East Side, MESSAGE FROM THE DIRECTOR West Side, All Around LA Welcome to the Center for the Art of Performance The Center for the Art of Performance is not a place. It’s more of a state of mind that embraces experimentation, encourages Photo by Ian Maddox a culture of the curious, champions disruptors and dreamers and One would have to admit that the masterful work of William Kentridge leaves supports the commitment and courage of artists. We promote virtually no artistic discipline unexplored, untampered with, or under-excavated in rigor, craft and excellence in all facets of the performing arts. service to his vigilant engagement with the known world. He has done x, y z, p, d, q, (installations, exhibitions, theater works, prints, drawings, animations, innumerable collaborations, etc.) and then some, over the arc of his career and there is nothing on the horizon line of his trajectory that indicates any notion of relenting any time 2017–18 SEASON VENUES soon. Royce Hall, UCLA Freud Playhouse, UCLA Over the years I have been asked to offer explanations and descriptions of the The Theatre at Ace Hotel Little Theater, UCLA works of William Kentridge while encountering it in numerous occasions around the Will Rogers State Historic Park world. As a curator, one is expected to possess the necessary expertise to rapidly summarize dimensional artistry. But in a gesture of truth, my attempts fail in UCLA’s Center for the Art of Performance (CAP UCLA) is dedicated to the advancement juxtaposition to the vastly better reality of experiencing his utter artistic singularity, of the contemporary performing arts in all disciplines—dance, music, spoken word and the staggering dimension of thoughtful care he takes in finding form. -

Abstracts' Book

International Conference SOCIOCULTURAL CROSSINGS AND BORDERS: MUSICAL MICROHISTORIES 4–7 September 2013, Vilnius Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre & Competition INTERDISCIPLINARY STUDIES IN MUSIC. NEW APPROACHES, METHODS AND CONCEPTIONS ABSTRACTS’ BOOK Compilers Rūta Stanevičiūtė, Rima Povilionienė Vilnius, 2013 UDK 78.072(063) So-25 Abstracts’ book of the International Conference Sociocultural Crossings and Borders: Musical Microhistories and Competition Interdisciplinary Studies in Music. New Approaches, Methods and Conceptions Conference organizers: Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre Lithuanian Composers’ Union Conference partners: Estonian Academy of Music and Theatre Jāzeps Vītols Latvian Academy of Music IMS study group ‘Shostakovich and his Epoch: Contemporaries, Culture and the State’ IMS study group ‘Stravinsky between East and West’ IMS study group ‘Music and Cultural Studies’ IMS Regional Association for Eastern Slavic Countries Lithuanian Art Museum – Vytautas Kasiulis Art Museum National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania Competition organizer Art-parkING Center for New Technology in the Arts Competition general partner Lithuanian Academy of Music and Theatre Support: Lithuanian Research Council Culture Support Foundation International Musicological Society (IMS) Lithuanian Art Museum – Vytautas Kasiulis Art Museum National Museum – Palace of the Grand Dukes of Lithuania Saulius Karosas Charity and Support Foundation Vytautas Landsbergis Foundation Music shop Open World (St Petersburg) Publishing house -

Scores 384 SCORES

383 Scores 384 SCORES GEORGES AURIC ______50409370 Phedre SCORES Salabert SEAS15642......................................................$30.00 For orchestra unless otherwise specified. MILTON BABBITT ______50237950 All Set (1957) 8 instruments JOHN ADAMS AMP96417-48 ..............................................................$50.00 ______50480014 Chairman Dances, The ______50237880 Composition 12 instruments AMP7974.......................................................................$30.00 AMP96418-52 ..............................................................$30.00 ______50480554 Grand Pianola ______50236700 String Quartet No. 2 (1954) Mini-score AMP7995.......................................................................$60.00 AMP6716-45 ................................................................$30.00 ______50488949 Harmonielehre CARL PHILLIP EMANUEL BACH AMP7991.......................................................................$60.00 ______50480489 Concerto in G Major for Organ (Winter) ______50480015 Harmonium Chorus & orchestra Harpsichord, piano, strings & continuo AMP7924.......................................................................$60.00 Sikorski SIK638P ..........................................................$32.00 ______50488934 Shaker Loops (revision) String orchestra AMP7983.......................................................................$40.00 JOHANN SEBASTIAN BACH ISAAC ALBENIZ ______50086400 6 Brandenburg Concertos Study score Ricordi RPR733.............................................................$24.95