Read Ebook {PDF EPUB} Big Mad on Campus by Al Feldstein Al Feldstein

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS American Comics SETH KUSHNER Pictures

LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS LEAPING TALL From the minds behind the acclaimed comics website Graphic NYC comes Leaping Tall Buildings, revealing the history of American comics through the stories of comics’ most important and influential creators—and tracing the medium’s journey all the way from its beginnings as junk culture for kids to its current status as legitimate literature and pop culture. Using interview-based essays, stunning portrait photography, and original art through various stages of development, this book delivers an in-depth, personal, behind-the-scenes account of the history of the American comic book. Subjects include: WILL EISNER (The Spirit, A Contract with God) STAN LEE (Marvel Comics) JULES FEIFFER (The Village Voice) Art SPIEGELMAN (Maus, In the Shadow of No Towers) American Comics Origins of The American Comics Origins of The JIM LEE (DC Comics Co-Publisher, Justice League) GRANT MORRISON (Supergods, All-Star Superman) NEIL GAIMAN (American Gods, Sandman) CHRIS WARE SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER SETH KUSHNER IRVING CHRISTOPHER (Jimmy Corrigan, Acme Novelty Library) PAUL POPE (Batman: Year 100, Battling Boy) And many more, from the earliest cartoonists pictures pictures to the latest graphic novelists! words words This PDF is NOT the entire book LEAPING TALL BUILDINGS: The Origins of American Comics Photographs by Seth Kushner Text and interviews by Christopher Irving Published by To be released: May 2012 This PDF of Leaping Tall Buildings is only a preview and an uncorrected proof . Lifting -

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore

Copyright 2013 Shawn Patrick Gilmore THE INVENTION OF THE GRAPHIC NOVEL: UNDERGROUND COMIX AND CORPORATE AESTHETICS BY SHAWN PATRICK GILMORE DISSERTATION Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in English in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 2013 Urbana, Illinois Doctoral Committee: Professor Michael Rothberg, Chair Professor Cary Nelson Associate Professor James Hansen Associate Professor Stephanie Foote ii Abstract This dissertation explores what I term the invention of the graphic novel, or more specifically, the process by which stories told in comics (or graphic narratives) form became longer, more complex, concerned with deeper themes and symbolism, and formally more coherent, ultimately requiring a new publication format, which came to be known as the graphic novel. This format was invented in fits and starts throughout the twentieth century, and I argue throughout this dissertation that only by examining the nuances of the publishing history of twentieth-century comics can we fully understand the process by which the graphic novel emerged. In particular, I show that previous studies of the history of comics tend to focus on one of two broad genealogies: 1) corporate, commercially-oriented, typically superhero-focused comic books, produced by teams of artists; 2) individually-produced, counter-cultural, typically autobiographical underground comix and their subsequent progeny. In this dissertation, I bring these two genealogies together, demonstrating that we can only truly understand the evolution of comics toward the graphic novel format by considering the movement of artists between these two camps and the works that they produced along the way. -

We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust

W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS W E SPOKE OUT COMIC BOOKS AND THE HOLOCAUST AND NEAL ADAMS RAFAEL MEDOFF CRAIG YOE INTRODUCTION AND THE HOLOCAUST AFTERWORD BY STAN LEE NEAL ADAMS MEDOFF RAFAEL CRAIG YOE LEE STAN “RIVETING!” —Prof. Walter Reich, Former Director, United States Holocaust Memorial Museum Long before the Holocaust was widely taught in schools or dramatized in films such asSchindler’s List, America’s youth was learning about the Nazi genocide from Batman, X-Men, and Captain America. Join iconic artist Neal Adams, the legend- ary Stan Lee, Holocaust scholar Dr. Rafael Medoff, and Eisner-winning comics historian Craig Yoe as they take you on an extraordinary journey in We Spoke Out: Comic Books and the Holocaust. We Spoke Out showcases classic comic book stories about the Holocaust and includes commentaries by some of their pres- tigious creators. Writers whose work is featured include Chris Claremont, Archie Goodwin, Al Feldstein, Robert Kanigher, Harvey Kurtzman, and Roy Thomas. Along with Neal Adams (who also drew the cover of this remarkable volume), artists in- clude Gene Colan, Jack Davis, Carmine Infantino, Gil Kane, Bernie Krigstein, Frank Miller, John Severin, and Wally Wood. In We Spoke Out, you’ll see how these amazing comics creators helped introduce an entire generation to a compelling and important subject—a topic as relevant today as ever. ® Visit ISBN: 978-1-63140-888-5 YoeBooks.com idwpublishing.com $49.99 US/ $65.99 CAN ® ACKNOWLEDGMENTS The authors are grateful to friends and colleagues who assisted with various aspects of this project: Kris Stone and Peter Stone, of Continuity Studios; Gregory Pan, of Marvel Comics; Thomas Wood, Jay Kogan, and Mandy Noack-Barr, of DC Comics; Dan Braun, of New Comic Company (Warren Publications); Corey Mifsud, Cathy Gaines-Mifsud, and Dorothy Crouch of EC Comics; Robert Carter, Jon Gotthold, Michelle Nolan, Thomas Martin, Steve Fears, Rich Arndt, Kevin Reddy, Steve Bergson, and Jeff Reid, who provided information or scans; Jon B. -

Zatanna and the House of Secrets Graphic Novels for Kids & Teens 741.5 Dc’S New Youth Movement Spring 2020 - No

MEANWHILE ZATANNA AND THE HOUSE OF SECRETS GRAPHIC NOVELS FOR KIDS & TEENS 741.5 DC’S NEW YOUTH MOVEMENT SPRING 2020 - NO. 40 PLUS...KIRBY AND KURTZMAN Moa Romanova Romanova Caspar Wijngaard’s Mary Saf- ro’s Ben Pass- more’s Pass- more David Lapham Masters Rick Marron Burchett Greg Rucka. Pat Morisi Morisi Kieron Gillen The Comics & Graphic Novel Bulletin of satirical than the romantic visions of DC Comics is in peril. Again. The ever- Williamson and Wood. Harvey’s sci-fi struggling publisher has put its eggs in so stories often centered on an ordinary many baskets, from Grant Morrison to the shmoe caught up in extraordinary circum- “New 52” to the recent attempts to get hip with stances, from the titular tale of a science Brian Michael Bendis, there’s hardly a one left nerd and his musclehead brother to “The uncracked. The first time DC tried to hitch its Man Who Raced Time” to William of “The wagon to someone else’s star was the early Dimension Translator” (below). Other 1970s. Jack “the King” Kirby was largely re- tales involved arrogant know-it-alls who sponsible for the success of hated rival Marvel. learn they ain’t so smart after all. The star He was lured to join DC with promises of great- of “Television Terror”, the vicious despot er freedom and authority. Kirby was tired of in “The Radioactive Child” and the title being treated like a hired hand. He wanted to character of “Atom Bomb Thief” (right)— be the idea man, the boss who would come up with characters and concepts, then pass them all pay the price for their hubris. -

2019-05-06 Catalog P

Pulp-related books and periodicals available from Mike Chomko for May and June 2019 Dianne and I had a wonderful time in Chicago, attending the Windy City Pulp & Paper Convention in April. It’s a fine show that you should try to attend. Upcoming conventions include Robert E. Howard Days in Cross Plains, Texas on June 7 – 8, and the Edgar Rice Burroughs Chain of Friendship, planned for the weekend of June 13 – 15. It will take place in Oakbrook, Illinois. Unfortunately, it doesn’t look like there will be a spring edition of Ray Walsh’s Classicon. Currently, William Patrick Maynard and I are writing about the programming that will be featured at PulpFest 2019. We’ll be posting about the panels and presentations through June 10. On June 17, we’ll write about this year’s author signings, something new we’re planning for the convention. Check things out at www.pulpfest.com. Laurie Powers biography of LOVE STORY MAGAZINE editor Daisy Bacon is currently scheduled for release around the end of 2019. I will be carrying this book. It’s entitled QUEEN OF THE PULPS. Please reserve your copy today. Recently, I was contacted about carrying the Armchair Fiction line of books. I’ve contacted the publisher and will certainly be able to stock their books. Founded in 2011, they are dedicated to the restoration of classic genre fiction. Their forté is early science fiction, but they also publish mystery, horror, and westerns. They have a strong line of lost race novels. Their books are illustrated with art from the pulps and such. -

History of Comic Art Course Number: AH 3657 01 Class Meets: R, 6:30 PM - 9:00 PM, 01/17/17 - 05/09/17 Classroom Location: 432

Course Name: History of Comic Art Course Number: AH 3657 01 Class Meets: R, 6:30 PM - 9:00 PM, 01/17/17 - 05/09/17 Classroom Location: 432 Faculty Name: Pistelli, John MCAD Email Address: [email protected] MCAD Telephone Number, Academic Affairs: 612-874-3694 Office Hours: R, 5:30-6:30 Office Location: 306 Faculty Biography: John Pistelli holds a PhD in English literature from the University of Minnesota. His academic interests include modern and contemporary fiction, literary modernism, literary theory and aesthetics, comics, and creative writing. His fiction, criticism, and poetry have appeared in Rain Taxi, The Millions, Revolver, The Stockholm Review of Literature, Atomic, Five2One, The Amaranth Review, and elsewhere. He is also the author of The Ecstasy of Michaela: a novella (Valhalla Press). Course Description: Although comics now include a vast collection of different articulations of image and text, their shared history reflects the movement from strictly pulp publications on cheap paper created by assembly-line artists to complex stories with provocative images. This course follows the history of comic art from The Yellow Kid to global manifestations of the art form, such as Japanese manga and French BD. The development and range of image and textual forms, styles, and structures that differentiate the vast compendium of such work inform the discourse in class. Classes are primarily lecture with some discussion. Prerequisite: Introduction to Art and Design History 2 (may be taken concurrently) or instructor permission Outcomes: Demonstrate a familiarity with key styles, themes, and trends in the history of comic art. Identify the role historical, technical, cultural, and social change played in the development of comic art. -

|||GET||| Superheroes and American Self Image 1St Edition

SUPERHEROES AND AMERICAN SELF IMAGE 1ST EDITION DOWNLOAD FREE Michael Goodrum | 9781317048404 | | | | | Art Spiegelman: golden age superheroes were shaped by the rise of fascism International fascism again looms large how quickly we humans forget — study these golden age Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition hard, boys and girls! Retrieved June 20, Justice Society of America vol. Wonder Comics 1. One of the ways they showed their disdain was through mass comic burnings, which Hajdu discusses Alysia Yeoha supporting character created by writer Gail Simone for the Batgirl ongoing series published by DC Comics, received substantial media attention in for being the first major transgender character written in a contemporary context in a mainstream American comic book. These sound effects, on page and screen alike, are unmistakable: splash art of brightly-colored, enormous block letters that practically shout to the audience for attention. World's Fair Comics 1. For example, Black Panther, first introduced inspent years as a recurring hero in Fantastic Four Goodrum ; Howe Achilles Warkiller. The dark Skull Man manga would later get a television adaptation and underwent drastic changes. The Senate committee had comic writers panicking. Howe, Marvel Comics Kurt BusiekMark Bagley. During this era DC introduced the Superheroes and American Self Image 1st edition of Batwoman inSupergirlMiss Arrowetteand Bat-Girl ; all female derivatives of established male superheroes. By format Comic books Comic strips Manga magazines Webcomics. The Greatest American Hero. Seme and uke. Len StrazewskiMike Parobeck. This era saw the debut of one of the earliest female superheroes, writer-artist Fletcher Hanks 's character Fantomahan ageless ancient Egyptian woman in the modern day who could transform into a skull-faced creature with superpowers to fight evil; she debuted in Fiction House 's Jungle Comic 2 Feb. -

Sfrareview in This Issue 312 Spring 2015

312 Spring 2015 Editor Chris Pak SFRA University of Lancaster, Bailrigg, Lan- A publicationRe of the Scienceview Fiction Research Association caster LA1 4YW. [email protected] Managing Editor In this issue Lars Schmeink Universität Hamburg, Institut für Anglis- SFRA Review Business tik und Amerikanistik, Von Melle Park 6 Gearing Up ............................................................................................................2 20146 Hamburg. W. [email protected] SFRA Business Nonfiction Editor #SFRA2015 ............................................................................................................2 Dominick Grace Live Long and Prosper .........................................................................................3 Brescia University College, 1285 Western Sideways in Time [conference report] ..............................................................3 Rd, London ON, N6G 3R4, Canada phone: 519-432-8353 ext. 28244. BSLS: British Society for Literature and Science [conference report] ..........5 [email protected] Feature 101 Assistant Nonfiction Editor Teaching Science Fiction .....................................................................................7 Kevin Pinkham College of Arts and Sciences, Nyack To Bottom Out: An Incomplete Guide to the New Venezuelan SF ............14 College, 1 South Boulevard, Nyack, NY 10960, phone: 845-675-4526845-675- 4526. Nonfiction Reviews [email protected] The American Shore: Meditations on a Tale of Science Fiction by Thomas M. Disch -

Copy of Graphic Novel Title List MASTER.Xlsx

Graphic Novels Title Author Artist Call No. Year 300 Miller, Frank Miller, Frank OVERSIZE PN6727.M55 T57 1999 1999 9/11 report: a graphic adaptation Jacobson, Colon HV6432. 7. J33 2006 2006 A Mad look at old movies DeBartolo, Dick PN6727.D422 M68 1973 1973 Abandon the old in Tokyo Tatsumi, Yoshihiro PN6790. J34 T27713 2006 2006 Absolute sandman. Volume one Gaiman, Neil Keith, Sam [et al.] PR6057. A319 A27 v.1 2006 2006 Absolutely no U.S. personnel permitted beyond this point DS557.A61 L4 1972 1972 Achewood Onstad, Chris Onstad, Chris PN6728. A25 O57 2004 2004 Acme Novelty Library Ware, Chris Ware, Chris OVERSIZE. PN6727. W285 A6 2005 2005 Adventures of Super Diaper Baby: the first graphic novel Beard, George Hutchins, Harold CURRLIB. 813 P639as 2002 Alex Kalesniko, Mark Kalesniko, Mark PN6727. K2437 A43 2006 2006 Alias the cat! Deitch, Kim Dietch, Kim PN6727. D383 A45 2007 2007 Alice in Sunderland Talbot, Bryan Talbot, Bryan PN6727. T3426 A44 2007 2007 Aliens Omnibus Vol. 4 Various Various PN6728.A463 O46 v. 4 2008 2008 All‐new, all‐different X‐men Pop‐up Ed. By Repchuck, Caroline PN6728.X536 A55 2007 2007 All‐star Superman Morrison, Grant Quitely, Frank PN6728. S9 M677 2007 American Presidency in political cartoons 1776‐1976 Various E176.1 .A655 1976b 1976 Anime encyclopedia: a guide to Japanesee animation since 1917 Clements, Jonathan REF. NC1766. J3 C53 2006 2006 Arkham Asylum: A Serious Place on a Serious Earth Morrison, Grant McKean, Dave PN6728.B36 A74 2004 2004 Arrival Tan, Shaun CURRLIB. 823 T161ar 2007 2007 Assassin's road Koike, Kazuo Miller, Frank PN6790. -

Free Catalog

Featured New Items DC COLLECTING THE MULTIVERSE On our Cover The Art of Sideshow By Andrew Farago. Recommended. MASTERPIECES OF FANTASY ART Delve into DC Comics figures and Our Highest Recom- sculptures with this deluxe book, mendation. By Dian which features insights from legendary Hanson. Art by Frazetta, artists and eye-popping photography. Boris, Whelan, Jones, Sideshow is world famous for bringing Hildebrandt, Giger, DC Comics characters to life through Whelan, Matthews et remarkably realistic figures and highly al. This monster-sized expressive sculptures. From Batman and Wonder Woman to The tome features original Joker and Harley Quinn...key artists tell the story behind each paintings, contextualized extraordinary piece, revealing the design decisions and expert by preparatory sketches, sculpting required to make the DC multiverse--from comics, film, sculptures, calen- television, video games, and beyond--into a reality. dars, magazines, and Insight Editions, 2020. paperback books for an DCCOLMSH. HC, 10x12, 296pg, FC $75.00 $65.00 immersive dive into this SIDESHOW FINE ART PRINTS Vol 1 dynamic, fanciful genre. Highly Recommened. By Matthew K. Insightful bios go beyond Manning. Afterword by Tom Gilliland. Wikipedia to give a more Working with top artists such as Alex Ross, accurate and eye-opening Olivia, Paolo Rivera, Adi Granov, Stanley look into the life of each “Artgerm” Lau, and four others, Sideshow artist. Complete with fold- has developed a series of beautifully crafted outs and tipped-in chapter prints based on films, comics, TV, and ani- openers, this collection will mation. These officially licensed illustrations reign as the most exquisite are inspired by countless fan-favorite prop- and informative guide to erties, including everything from Marvel and this popular subject for DC heroes and heroines and Star Wars, to iconic classics like years to come. -

JUDGE of BEAUTY Estate of the Honorable Paul H

STEPHEN GEPPI DIXIE CARTER SANDY KOUFAX MAGAZINE FOR THE INTELLIGENT COLLECTOR SPRing 2009 $9.95 JUDGE OF BEAUTY Estate of the Honorable Paul H. Buchanan Jr. includes works by landmark figures in the canon of American Art CONTENTS HIGHLIGHTS JUDGE OF BEAUTY Estate of the Honorable Paul H. 30 Buchanan Jr. includes works by landmark figures in the canon of American art SUPER COLLectoR A relentless passion for classic American 42 pop culture has turned Stephen Geppi into one of the world’s top collectors IT’S A Mad, Mad, Mad, Mad (MagaZINE) WORLD 50 Demand for original cover art reflects iconic status of humor magazine SIX THINgs I LeaRNed FRom WARREN Buffett 56 Using the legendary investor’s secrets of success in today’s rare-coins market IN EVERY ISSUE 4 Staff & Contributors 6 Auction Calendar 8 Looking Back … 1934 10 News 62 Receptions 63 Events Calendar 64 Experts 65 Consignment Deadlines On the cover: McGregor Paxton’s Rose and Blue from the Paul H. Buchanan Jr. Collection (page 30) Movie poster for the Mickey Mouse short The Mad Doctor, considered one of the rarest of all Disney posters, from the Stephen Geppi collection (page 42) HERITAGE MAGAZINE — SPRING 2009 1 CONTENTS TREAsures 12 MOVIE POSTER: One sheet for 1933’s Flying Down to Rio, which introduced Fred Astaire and Ginger Rogers to the world 14 COI N S: New Orleans issued 1854-O Double Eagle among rarest in Liberty series 16 FINE ART: Julian Onderdonk considered the father of Texas painting Batman #1 DC, 1940 CGC FN/VF 7.0, off-white to white pages Estimate: $50,000+ From the Chicorel Collection Vintage Comics & Comic Art Signature® Auction #7007 (page 35) Sandy Koufax Game-Worn Fielder’s Glove, 1966 Estimate: $60,000+ Sports Memorabilia Signature® Auction #714 (page 26) 2 HERITAGE MAGAZINE — SPRING 2009 CONTENTS AUCTION PrevieWS 18 ENTERTAINMENT: Ernie Kovacs and Edie Adams left their mark on the entertainment industry 23 CURRENCY: Legendary Deadwood sheriff Seth Bullock signed note as bank officer 24 MILITARIA: Franklin Pierce went from battlefields of war to the U.S. -

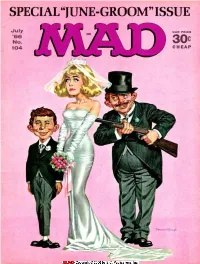

ISSUE for a WILD NEW SOUND • • • Listen to ALFRED E

SPECIAL"JUNE-GROOM" ISSUE FOR A WILD NEW SOUND • • • Listen to ALFRED E. NEUMAN VOCALIZE IT'S A GAS!" on this real 1 33 /3R.P.M RECORD You get it as a FREE BONUS in this latest MAD ANNUAL Which also contains articles, ad satires and other garbage — the best from past issues! PLUS A SPECIAL FREE BONUS WITH A WILD NEW SOUND: ON SALE NOW! Rush out and buy a copy! ON A REAL 33/3RPM RECORD It's a "Sound Investment"! N UMBER 104 JULY 1966 VITAL FEATURES ADVERTISING CAMPAIGNS 'There's one thing we know for sure about the speed of light: WITH ULTERIOR It gets here too early in the morning!"—Alfred E. Neuman MOTIVES PG.4 WILLIAM M. GAINES publisher ALBERT B. FELDSTEIN editor JOHN PUTNAM art director LEONARD BRENNER production JERRY DE FUCCIO, NICK MECLIN associate editors MARTIN J. SCHEIMAN lawsuits RICHARD BERNSTEIN publicity GLORIA ORLANDO, CELIA MORELLI, RICHARD GRILLO Subscriptions CONTRIBUTING ARTISTS AND WRITERS the usual gang of idiots FUTURE WIT AND WISDOM DEPARTMENTS BOOKS PG. 10 BERGS-EYE VIEW DEPARTMENT The Lighter Side Of High School 28 DON MARTIN DEPARTMENT In The Hospital 13 Later On In The Hospital 25 Still Later On In The Hospital 42 FUNNY-BONE-HEADS DEPARTMENT MAD VISITS THE AMERICAN Future Wit And Wisdom Books •. 10 MEDIOCRITY HIGHWAY RIBBERY DEPARTMENT ACADEMY Road Signs We'd Really Like To See 32 PG. 21 INSTITUTION FOR THE CRIMINALLY INANE DEPARTMENT MAD Visits The American Mediocrity Academy 21 LETTERS DEPARTMENT Random Samplings Of Reader Mail 2 LICKING THE PROBLEM DEPARTMENT Postage Stamp Advertising 34 MIXING MARGINAL THINKING DEPARTMENT POLITICS Drawn-Out Dramas ** WITH MICROFOLK DEPARTMENT CAREERS Another MAD Peek Through The Microscope 8 PG.