Family Law: Husband and Wife

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Understanding Marriage and Families Across Time and Place M01 ESHL8740 12 SE C01.QXD 9/14/09 5:28 PM Page 3

M01_ESHL8740_12_SE_C01.QXD 9/14/09 5:28 PM Page 2 part I Understanding Marriage and Families across Time and Place M01_ESHL8740_12_SE_C01.QXD 9/14/09 5:28 PM Page 3 chapter 1 Defining the Family Institutional and Disciplinary Concerns Case Example What Is a Family? Is There a Universal Standard? What Do Contemporary Families Look Like? Ross and Janet have been married more than forty-seven years. They have two chil- dren, a daughter-in-law and a son-in-law, and four grandsons. Few would dispute the notion that all these members are part of a common kinship group because all are related by birth or marriage. The three couples involved each got engaged, made a public announcement of their wedding plans, got married in a religious ceremony, and moved to separate residences, and each female accepted her husband’s last name. Few would question that each of these groups of couples with their children constitutes a family, although a question remains as to whether they are a single family unit or multiple family units. More difficult to classify are the families of Vernon and Jeanne and their chil- dren. Married for more than twenty years, Vernon and Jeanne had four children whom have had vastly different family experiences. Their oldest son, John, moved into a new addition to his parents’ house when he was married and continues to live there with his wife and three children. Are John, his wife, and his children a separate family unit, or are they part of Vernon and Jeanne’s family unit? The second child, Sonia, pursued a career in marketing and never married. -

Psychoanalytic Conceptions of Marriage and Marital Relationships 381 Been Discussing, Since These Figures Are Able to Reanimate Pictures of Their Mother Or Father

UNIVERSITY OF NIŠ The scientific journal FACTA UNIVERSITATIS Series: Philosophy and Sociology Vol.2, No 7, 2000 pp. 379 - 389 Editor of series: Gligorije Zaječaranović Address: Univerzitetski trg 2, 18000 Niš, YU Tel: +381 18 547-095, Fax: +381 18 547-950 PSYCHOANALYTIC CONCEPTIONS OF MARRIAGE AND MARITAL RELATIONSHIPS UDC 159.964.28+173.1+340.61 Zorica Marković University of Niš, Faculty of Philosophy, Niš, Yugoslavia Abstract. This work disclusses marital types and merital relationships as by several psychoanalysts: Sigmund Freud, Annie Reich, Helene Deutch, Knight Aldrich and Bela Mittelman. It analyzes kinds of relations hips, dynamics of interaction and inner mechanisms of interaction.Comparing marital types of the mentioned authors it can be seen that there is agreement among them and that they mainly represent further elaboration and "topic variation" of the basic marital types which are discussed by Sigmund Freud: anaclictic and narcissistic.Also, it can be concluded that all analysed marital types possess several common characteristics: 1. they are defined by relationships in childhood with parents or other important persons with whom a child was in touch; 2. dynamics of partner relationships is defined by unconscious motives; 3. same kinds of relationships and same type of partner selection a person repeats in all further attempts in spite of the fact that it does not give satisfactory results. Key words: psychoanalysis, marriage, partner, choice, relationships According to Si gmund Fr e ud , the founder of psychoanalysis, marital partner choice, as well as marital relationships, are defined much before marriage was concluded. Relationship with marital partner is determined by relationships with parents and important persons in one's childhood. -

Outline of the Book I. the Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A

EPHESIANS.43 P a g e | 1 Outline of the Book I. The Glorious Position of the Body of Christ (1:1-3:21) A. Greetings (1:1-2) B. The Believer’s “Astounding Station” in Christ, to the praise of His glory (1:3-14) --- The Grace of the Father (1:3-6) --- The Grace of the Son (1:7-12) --- The Grace of the Spirit (1:13-14) C. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 1 (1:15-23) D. The Believer’s Collective Transport (2:1-10) --- Dead in Trespasses (2:1-3) --- Made Alive with Christ (2:4-10) E. Unified in Christ (2:11-22) --- Brought Near by the Blood (2:11-13) --- The Cross Creates One New Man (2:14-18) a. By Abolishing the Law (2:14-15) b. By Reconciling Us to the Father (2:16-18) --- Fellow Citizens in the Household of God (2:19-22) F. The Mystery of the Gospel (3:1-3:13) --- Prayer Interrupted (3:1) --- The Dispensation of God’s Grace (3:2-5) --- The Gentiles are Fellow Heirs (3:6-13) G. Paul’s Motivated Prayer & Praise 2 (3:14-21) II. The Glorious Practice of the Body of Christ (4:1-6:24) A. A Worthy Walk that Promotes Unity (4:1-6) B. Measures of Grace for Equipping the Body (4:7-16) C. Exhortation to Put on the New Self (4:17-24) D. Conduct that Benefits the Body (4:25-32) E. Serious Calling/Serious Consequences (5:1-21) F. Serious Calling Explained (5:22-6:20) --- The Example of Marriage (5:22-33) --- Parental Relationships (6:1-4) --- Occupational Relationships (6:5-9) --- Spiritual Opposition (6:10-20) G. -

Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage

Utah Code Title 30. Husband and Wife Chapter 1 Marriage 30-1-1 Incestuous marriages void. (1) The following marriages are incestuous and void from the beginning, whether the relationship is legitimate or illegitimate: (a) marriages between parents and children; (b) marriages between ancestors and descendants of every degree; (c) marriages between siblings of the half as well as the whole blood; (d) marriages between: (i) uncles and nieces or nephews; or (ii) aunts and nieces or nephews; (e) marriages between first cousins, except as provided in Subsection (2); or (f) marriages between any individuals related to each other within and not including the fifth degree of consanguinity computed according to the rules of the civil law, except as provided in Subsection (2). (2) First cousins may marry under the following circumstances: (a) both parties are 65 years of age or older; or (b) if both parties are 55 years of age or older, upon a finding by the district court, located in the district in which either party resides, that either party is unable to reproduce. Amended by Chapter 317, 2019 General Session 30-1-2 Marriages prohibited and void. (1) The following marriages are prohibited and declared void: (a) when there is a spouse living, from whom the individual marrying has not been divorced; (b) except as provided in Subsection (2), when an applicant is under 18 years old; and (c) between a divorced individual and any individual other than the one from whom the divorce was secured until the divorce decree becomes absolute, and, if an appeal is taken, until after the affirmance of the decree. -

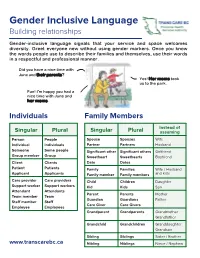

Gender Inclusive Language Building Relationships

Gender Inclusive Language Building relationships Gender-inclusive language signals that your service and space welcomes diversity. Greet everyone new without using gender markers. Once you know the words people use to describe their families and themselves, use their words in a respectful and professional manner. Did you have a nice time with June and their parents? Yes! Her moms took us to the park. Fun! I'm happy you had a nice time with June and her moms. Individuals Family Members Instead of Singular Plural Singular Plural assuming Person People Spouse Spouses Wife Individual Individuals Partner Partners Husband Someone Some people Significant other Significant others Girlfriend Group member Group Sweetheart Sweethearts Boyfriend Client Clients Date Dates Patient Patients Family Families Wife / Husband Applicant Applicants Family member Family members and kids Care provider Care providers Child Children Daughter Support worker Support workers Kid Kids Son Attendant Attendants Parent Parents Mother Team member Team Guardian Guardians Father Staff member Staff Care Giver Care Givers Employee Employees Grandparent Grandparents Grandmother Grandfather Grandchild Grandchildren Granddaughter Grandson Sibling Siblings Sister / Brother www.transcarebc.ca Nibling Niblings Niece / Nephew ii Pronouns (using they in the singular) If you are in a setting where your interactions with people are brief, you may not have time to get to know the person. Using the singular they in these situations can help to avoid pronoun mistakes. subject They They are waiting at the door. object Them The form is for them. possessive Their Their parents will pick them up at 3pm. adjective possessive Theirs They said the wheelchair is not theirs. -

Code of Ethics of the Family

Code of Ethics of the Family WANGO Copyright ©2010 by World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (WANGO) Code of Ethics of the Family Preface The family is the core unit of society. The Universal Declaration of Human Rights, enacted without dissent by the United Nations in 1948, notes this in stating that “the family is the natural and Stresses of urbanization and modernity have placed strains on the family and on marriage. This Code fundamental group unit of society and is entitled to protection by society and the State.” If society is designed to provide a frame of reference of those common features that help make successful were to be compared to an organism, families would be the cells. It is in the state’s interest to protect families. the family because, as the cornerstone of society, healthy families lead to a healthy society, analogous to healthy cells being necessary for a healthy organism. Developed under the auspices of the World Association of Non-Governmental Organizations (WANGO), in partnership with many organizations, the Code of Ethics of the Family was formulated Essentially, the family is the training ground of the heart and a textbook in which the husband by an international committee representing the broad spectrum of societies from all regions of the and wife are joint authors. It is in the family where we learn to care for others beyond ourselves, world. The original founding vision was provided by H.E. Dr. Abdelaziz Hegazy, former Prime to sacrifice ourselves for others, to love others. The most natural environment for a child to grow Minister of Egypt, and the Pennsylvania Family Coalition was the original founding partner providing mentally and spiritually from a state of selfishness and selfish behavior to unselfishness is the family practical assistance with the development of the Code. -

Antigone's Line

Bulletin de la Société Américaine de Philosophie de Langue Française Volume 14, Number 2, Fall 2005 Antigone’s Line Mary Beth Mader “Leader: What is your lineage, stranger? Tell us—who was your father? Oedipus: God help me! Dear girl, what must I suffer now? Antigone: Say it. You’re driven right to the edge.”1 Sophocles’ Antigone has solicited many superlatives. Hölderlin considered the play to be the most difficult, the most enigmatic and the most essentially Greek of plays. This paper treats a matter of enigma in the play, one that is crucial to understanding the central stakes of the drama. Its main purpose is to propose a novel account of this enigma and briefly to contrast this account with two other readings of the play. One passage in particular has prompted the view that the play is extremely enigmatic; it is a passage that has been read with astonishment by many commentators and taken to demand explanation. This is Antigone’s defense speech at lines 905-914. Here, she famously provides what appear to her to be reasons for her burying her brother Polynices against the explicit command of her king and uncle, Creon. Her claim is that she would not have deliberately violated Creon’s command, would not have ANTIGONE’S LINE intentionally broken his law or edict, had this edict barred her from burying a child or a husband of hers. She states that if her husband or child had died “there might have been another.” But since both her mother and father are dead, she reasons, “no brother could ever spring to light again.”2 Reasoning of this sort has a precedent in a tale found in Herodotus’ Histories, and Aristotle cites it in Rhetoric as an example of giving an explanation for something that one’s auditors may at first find incredible.3 To Aristotle, then, Antigone’s defense speech appears to have been “rhetorically satisfactory,” as Bernard Knox says.4 However, such a reception is rare among commentators.5 1. -

An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies

11 Close–Distant: An Essential Dichotomy in Australian Kinship Tony Jefferies Abstract This chapter looks at the evidence for the close–distant dichotomy in the kinship systems of Australian Aboriginal societies. The close– distant dichotomy operates on two levels. It is the distinction familiar to Westerners from their own culture between close and distant relatives: those we have frequent contact with as opposed to those we know about but rarely, or never, see. In Aboriginal societies, there is a further distinction: those with whom we share our quotidian existence, and those who live at some physical distance, with whom we feel a social and cultural commonality, but also a decided sense of difference. This chapter gathers a substantial body of evidence to indicate that distance, both physical and genealogical, is a conception intrinsic to the Indigenous understanding of the function and purpose of kinship systems. Having done so, it explores the implications of the close–distant dichotomy for the understanding of pre-European Aboriginal societies in general—in other words: if the dichotomy is a key factor in how Indigenes structure their society, what does it say about the limits and integrity of the societies that employ that kinship system? 363 SKIN, KIN AND CLAN Introduction Kinship is synonymous with anthropology. Morgan’s (1871) Systems of Consanguinity and Affinity of the Human Family is one of the founding documents of the discipline. It also has an immediate connection to Australia: one of the first fieldworkers to assist Morgan in gathering his data was Lorimer Fison, who, later joined by A. -

Levinas Between Agape and Eros

Levinas Between Agape and Eros CLAIRE KATZ, Texas A&M University Anders Nygren's Agape and Eros, first published in the 1930s, was a landmark treatment of the radical distinction between eros and agape.! Realizing that the Christian Bible makes large use of agape and little use of eros, Nygren seeks to understand why this is the case. Eros, Nygren tells us, is largely associated with Plato while agape is largely associated with Paul. Where eros is the desire to behold and participate in divine attributes, to make them part of oneself, agape is God's love freely bestowed on us. Although the most colloquial usage of eros does not point to a religious connotation, eros, like agape, is deeply religious in its original meaning, even as the two terms differ in significant ways. We can see remnants of this same discussion in the ethical project of Emmanuel Levinas, which became the subject of terrific criticism, pre cisely because he separated the ethical relation from the erotic experi ence. As a result, Levinas's commentators frequently compare Levinas's ethics to Christian agape. 2 Using the same distinction between agape and eros, even if implicitly, these commentators conclude that if Levinas distances the ethical relation from eros, his ethics must be like agape. Conversely, other commentators, for example, Luce Irigaray, prefer to bring together Levinas's ethics and eros while still maintaining some of the structure of Levinasian ethics. 3 That is, they are not satisfied with this separation, yet they are persuaded by some of the structure that identifies Levinas's ethical relation. -

The Evolution of Marital Agency and the Meaning of Marriage

Penn State Law eLibrary Journal Articles Faculty Works 2008 In Good Times and in Debt: The volutE ion of Marital Agency and the Meaning of Marriage Marie T. Reilly Penn State Law Follow this and additional works at: http://elibrary.law.psu.edu/fac_works Part of the Family Law Commons, and the Property Law and Real Estate Commons Recommended Citation Source:https://works.bepress.com/marie_reilly/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Faculty Works at Penn State Law eLibrary. It has been accepted for inclusion in Journal Articles by an authorized administrator of Penn State Law eLibrary. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Marie T. Reilly* In Good Times and in Debt: The Evolution of Marital Agency and the Meaning of Marriage TABLE OF CONTENTS I. Introduction .......................................... 373 II. The Effect of Married Women's Property Reform on Creditor's Rights Against Married People .............. 376 III. Spouses' Responsibility for Each Other Under Modern M arriage ............................................. 397 A. Status-Based Shared Liability ..................... 399 B. Im puted Liability ................................. 403 IV. The Effect of Change in Marriage on Marital Agency: Som e Observations .................................... 413 V . Conclusion ............................................ 419 I. INTRODUCTION A person's liability for the debts his or her spouse was once an in- variable attribute of marital status. Two individual persons merged into one legal persona. The husband managed the legal persona and acted as the exclusive agent for both spouses., Today, marriage is © Copyright held by the NEBRASKA LAW REVIEW. * Professor of Law, The Pennsylvania State University Dickinson School of Law, University Park, Pennsylvania, [email protected]. -

Sample Wedding Ceremony

Sample Wedding Ceremony Notary states, "Dearly beloved, we are gathered here today (tonight) to join this man and this woman in (holy) matrimony." Exchange of Vows Notary asks the man, "(his name), do you take this woman to be your wife, to live together in (holy) matrimony, to love her, to honor her, to comfort her, and to keep her in sickness and in health, forsaking all others, for as long as you both shall live?" Man answers, "I do." Notary asks the woman, "(her name), do you take this man to be your husband, to live together in (holy) matrimony, to love him, to honor him, to comfort him, and to keep him in sickness and in health, forsaking all others, for as long as you both shall live?" Woman answers, "I do." Notary states, "Repeat after me." To the man: "I, (his name), take you (her name ), to be my wife, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, till death do us part." To the woman: "I, (her name), take you (his name ), to be my husband, to have and to hold from this day forward, for better, for worse, for richer, for poorer, in sickness and in health, to love and to cherish, till death do us part." Exchange of Rings Notary asks the man to place the ring on the woman's finger and to repeat the following, "I give you this ring as a token and pledge of our constant faith and abiding love." (Repeat the same for the woman). -

Family Law: Husband and Wife Joseph W

SMU Law Review Volume 40 Article 3 Issue 1 Annual Survey of Texas Law 1986 Family Law: Husband and Wife Joseph W. McKnight Follow this and additional works at: https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr Recommended Citation Joseph W. McKnight, Family Law: Husband and Wife, 40 Sw L.J. 1 (1986) https://scholar.smu.edu/smulr/vol40/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law Journals at SMU Scholar. It has been accepted for inclusion in SMU Law Review by an authorized administrator of SMU Scholar. For more information, please visit http://digitalrepository.smu.edu. FAMILY LAW: HUSBAND AND WIFE by Joseph W. McKnight* I. STATUS M ARRIAGE LICENSE. Section 1.51 of the Family Code, with some exceptions, forbids the county clerk from issuing a marriage license to an applicant under eighteen years of age.1 The Code also provides, however, that a person who has been married has "the power and capacity of an adult."' 2 The Attorney General has given an opinion that the clerk may not issue a license to a person under eighteen, regardless of that person's prior marital status.3 A person who has acquired adulthood through marriage should not lose that status on divorce, particularly with respect to contracting another marriage. Section 1.51 should, therefore, be amended to rectify this oversight. Informal Marriage. A federal court sitting in another jurisdiction consid- ered the validity of a Texas informal marriage. 4 The parties as husband and wife executed a deed to a house, in which conveyance they waived all their homestead rights.