Unemployment (Fears) and Deflationary

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mankiw Coursebook

e Forward Guidance Forward Guidance Forward guidance is the practice of communicating the future path of monetary Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars policy instruments. Such guidance, it is argued, will help sustain the gradual recovery that now seems to be taking place while central banks unwind their massive and Market Participants balance sheets. This eBook brings together a collection of contributions from central Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market Participants bank officials, researchers at universities and central banks, and financial market practitioners. The contributions aim to discuss what economic theory says about Edited by Wouter den Haan forward guidance and to clarify what central banks hope to achieve with it. With contributions from: Peter Praet, Spencer Dale and James Talbot, John C. Williams, Sayuri Shirai, David Miles, Tilman Bletzinger and Volker Wieland, Jeffrey R Campbell, Marco Del Negro, Marc Giannoni and Christina Patterson, Francesco Bianchi and Leonardo Melosi, Richard Barwell and Jagjit S. Chadha, Hans Gersbach and Volker Hahn, David Cobham, Charles Goodhart, Paul Sheard, Kazuo Ueda. CEPR 77 Bastwick Street, London EC1V 3PZ Tel: +44 (0)20 7183 8801 A VoxEU.org eBook Email: [email protected] www.cepr.org Forward Guidance Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market Participants A VoxEU.org eBook Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) Centre for Economic Policy Research 3rd Floor 77 Bastwick Street London, EC1V 3PZ UK Tel: +44 (0)20 7183 8801 Email: [email protected] Web: www.cepr.org © 2013 Centre for Economic Policy Research Forward Guidance Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market Participants A VoxEU.org eBook Edited by Wouter den Haan a Centre for Economic Policy Research (CEPR) The Centre for Economic Policy Research is a network of over 800 Research Fellows and Affiliates, based primarily in European Universities. -

Unemployment Crises

Unemployment Crises Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau∗ Lu Zhang† Carnegie Mellon University The Ohio State University and NBER December 2013‡ Abstract A search and matching model, when calibrated to the mean and volatility of unemployment in the postwar sample, can potentially explain the unemployment crisis in the Great Depression. The limited responses of wages from credible bargaining to labor market conditions, along with the congestion externality from matching frictions, cause the unemployment rate to rise sharply in recessions but decline gradually in booms. The frequency, severity, and persistence of unem- ployment crises in the model are quantitatively consistent with U.S. historical time series. The welfare gain from eliminating business cycle fluctuations is large. JEL Classification: E24, E32, J63, J64. Keywords: Search and matching frictions, unemployment crises, the Great Depression, the un- employment volatility puzzle, nonlinear impulse response functions ∗Tepper School of Business, Carnegie Mellon University, 5000 Forbes Avenue, Pittsburgh PA 15213. Tel: (412) 268-4198 and e-mail: [email protected]. †Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 760A Fisher Hall, 2100 Neil Avenue, Columbus OH 43210; and NBER. Tel: (614) 292-8644 and e-mail: zhanglu@fisher.osu.edu. ‡We are grateful to Hang Bai, Andrew Chen, Daniele Coen-Pirani, Steven Davis, Paul Evans, Wouter Den Haan, Bob Hall, Dale Mortensen, Paulina Restrepo-Echavarria, Etienne Wasmer, Randall Wright, and other seminar participants at Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, Northwestern University, the Ohio State University, the 19th International Conference on Computing in Economics and Finance hosted by the Society for Computational Eco- nomics, the 2013 North American Summer Meeting of the Econometric Society, the Southwest Search and Matching workshop at University of Colorado at Boulder, University of California at Berkeley, University of California at Santa Cruz, and University of Southern California for helpful comments. -

ALBERT MARCET Curriculum Vitae September 2010 Personal Data

ALBERT MARCET Curriculum Vitae September 2010 Personal Data Address Department of Economics London School of Economics Houghton Street London WC2A 2AE United Kingdom [email protected] Age: 50 Fields of Specialization Macroeconomics Time Series Financial Economics Economic Dynamic Theory Education -Ph. D. in Economics, University of Minnesota, 1987 -Llicenciat in Economics, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona, 1982. Professional Experience Full time appointments: 2009- Professor of Economics, Department of Economics, London School of Economics 2004-2009 Research Professor, Institut d'Analisi Economica (CSIC). 1990-2003 Catedratic (Fulll professor), Universitat Pompeu Fabra 1 1986-90 Assistant Profesor, G.S.I.A., Carnegie Mellon University. 1984-86 Research Assistant, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. 1982-84 Teaching Assistant, Department of Economics, University of Minnesota. Other appointments 2006-2009 Adjunct Professor, IDEA doctoral program, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. 2006 Visiting Researcher (Wim Duisemberg Fellowship) European Cen- tral Bank. 2004-2006 Adjunct Professor, Universitat Pompeu Fabra 2001 Visiting Scholar, European Central Bank (July and December). 1997-2008 Visiting Professor, London Business School (three weeks a year). 1995-2006 Associate Researcher, CREI. 1996-97 Visiting Professor, CEMFI (Madrid). 1994 Outside Consultant, Research Department, Federal Reserve Bank of Minneapolis. 1990-92 Associate Profesor, G.S.I.A., Carnegie Mellon University, (on leave). 1989-90 Visiting Professor, Universitat Autonoma de Barcelona. Honors and Awards Plenary Session, SWIM conference, Auckland, New Zealand, 2009 Plenary Session CEF conference, Sydney, 2009 2 Plenary Session, Simposio AnalisisEconomico, Granada, 2007. President of the Spanish Economic Association, 2007. Wim Duisenberg Fellowship, European Central Bank, 2006. Plenary Session, European Symposium of Economic of Economic The- ory, ESSET, CEPR, 2002, Gerzensee. -

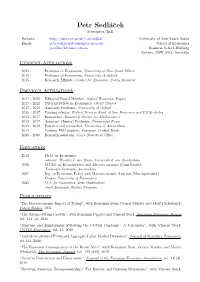

Petr Sedlácek

Petr Sedl´aˇcek November, 2020 Website: http://users.ox.ac.uk/∼econ0506 University of Oxford Email: [email protected] Department of Economics Manor Road Oxford OX1 3UQ, UK Current Position 2019 - Professor of Economics University of Oxford and Christ Church Other Appointments 2017 - Editorial Board Member Oxford Economic Papers 2015 - Research Affiliate Center for Economic Policy Research Previous Positions 2017 - 2019 Associate Professor University of Oxford 2016 - 2017 Visiting scholar Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and UC Berkeley 2014 - 2017 Researcher Hausdorff Center for Mathematics 2012 - 2017 Assistant (Junior) Professor Universit¨atBonn, Department of Economics 2011 - 2012 Postdoctoral researcher University of Amsterdam, Faculty of Economics and Business 2011 Visiting PhD student European Central Bank, Directorate General Research, Monetary Policy 2005 - 2006 Research assistant Czech Statistical Office, Department of Macroeconomic Analysis Education 2008 - 2011 Ph.D. in Economics advisor: Wouter J. den Haan Universiteit van Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2006 - 2008 M.Phil. in Econometrics and Macroeconomics (Cum Laude) Tinbergen Institute, Amsterdam, The Netherlands 2004 - 2005 M.A. in Economics (with Distinction) Joint European Studies Program Prague University of Economics, Staffordshire University, University of Antwerp 2002 - 2007 Ing. in Economic Policy and Macroeconomic Analysis (Msc equivalent) Prague University of Economics, Czech Republic Publications "The Nature of Firm Growth", 2020, with Benjamin Pugsley and Vincent Sterk, forthcoming at the American Economic Review. "Startups and Employment Following the COVID Pandemic: A Calculator", 2020, with Vincent Sterk, COVID Economics, 13. "The Economic Consequences of the Brexit Vote", 2017, with Benjamin Born, Gernot Mueller and Moritz Schularick, accepted at The Economic Journal. -

Anticipated Growth and Business Cycles in Matching Models

Anticipated Growth and Business Cycles in Matching Models Wouter J. DEN HAAN and Georg KALTENBRUNNER February 14, 2009 Abstract In a business cycle model that incorporates a standard matching framework, em- ployment increases in response to news shocks, even though the wealth e¤ect asso- ciated with the increase in expected productivity reduces labor force participation. The reason is that the matching friction induces entrepreneurs to increase investment in new projects and vacancies early. If there is underinvestment in new projects in the competitive equilibrium, then the e¢ ciency gains associated with an increase in employment make it possible that consumption, employment, output, as well as the investment in new and existing projects jointly increase before the actual increase in productivity materializes. If there is no underinvestment then investment in existing projects decreases, but total investment, consumption, employment, and output still jointly increase. Keywords: Pigou Cycles, Labor Force Participation, Productivity Growth JEL Classi…cation: E24, E32, J41 Den Haan: Department of Economics, University of Amsterdam, Roetersstraat 11, 1018 WB Amsterdam, The Netherlands and CEPR, London, United Kingdom. Email: [email protected]. Kaltenbrunner: McKinsey & Company, Inc., Magnusstraße 11, 50672 Köln, Germany. Email: [email protected]. The authors are grateful to an anonymous referee, Nir Jaimovitch, Franck Portier, and Sergio Rebelo for insightful comments. 1 1 Introduction 2 Economists have long recognized the importance of expectations in explaining economic 3 ‡uctuations. As early as 1927, Pigou postulated that ‘the varying expectations of business 4 men ... constitute the immediate cause and direct causes or antecedents of industrial ‡uc- 1 5 tuations.’ A recent episode where many academic and non-academic observers attribute 6 a key role to expectations is the economic expansion of the 1990s. -

TI Magazine Nr.14.Indd

tinbergen magazine 14, fall 2006 I n d e p t h Macroeconomic equilibrium models without the Walrasian auctioneer l Wouter den Haan Macroeconomics has changed Modifi cations to fi rst-generation considerably in the last few decades. Modern DSGE models l Wouter den Haan is macro is based on neoclassical economics DSGE models are more diffi cult to since July professor and microeconomic foundations. It started analyse than their predecessors, i.e., large of economics at the in the 1970s, and is constructed on two Keynesian computer models. If agents are University of Amsterdam important building blocks. The fi rst is the forward looking, and current economic and VICI scholar. rational expectations approach of Nobel behaviour depends on expectations about Previously, he was a Prize winner Robert Lucas. The second is the uncertain future, then solving the model professor of economics at the dynamic stochastic general equilibrium requires solving for agents’ decisions for all the University of California (DSGE) model. Although DSGE models are possible realisations, not just the ones that at San Diego and the often referred to as Real Business Cycle (RBC) are realised. Instead of solving for a time London Business School. models, because in earlier versions aggregate path, one must therefore fi nd a solution in a productivity was the sole exogenous random function space. variable, many other shocks have since been As computational and mathematical considered. Finn Kydland and Ed Prescott challenges were met, the models were received their Nobel Prize for developing modifi ed in many diff erent ways. For this type of model. -

Mortgages and Monetary Policy∗

Mortgages and Monetary Policy∗ Carlos Garriga†‡,FinnE.Kydland§ and Roman Sustekˇ ¶ September 4, 2016 Abstract Mortgages are long-term loans with nominal payments. Consequently, under incomplete asset markets, monetary policy can affect housing investment and the economy through the cost of new mortgage borrowing and real payments on outstanding debt. These channels, distinct from traditional real rate channels, are embedded in a general equilibrium model. The transmission mechanism is found to be stronger under adjustable- than fixed-rate mort- gages. Further, monetary policy shocks affecting the level of the nominal yield curve have larger real effects than transitory shocks, affecting its slope. Persistently higher inflation gradually benefits homeowners under FRMs, but hurts them immediately under ARMs. JEL Classification Codes: E32, E52, G21, R21. Keywords: Mortgage contracts, monetary policy, housing investment, redistribution, general equilibrium. ∗We thank John Campbell, Joao Cocco, Morris Davis, Wouter den Haan, Martin Schneider, Javier Villar Burke, Eric Young, and Stan Zin for helpful suggestions and Dean Corbae, Andra Ghent, Matteo Iacoviello, Amir Kermani, Bryan Routledge, and Arlene Wong for insightful conference discussions. We have also benefited from comments by seminar participants at the Bank of England, Birmingham, Carnegie Mellon, CERGE-EI, Essex, Glasgow, IHS Vienna, Indiana, Norwegian School of Economics, Ohio State, Riksbank, Royal Holloway, San Francisco Fed, Southampton, St. Louis Fed, Surrey, and Tsinghua University and par- ticipants at the Bundesbank Workshop on Credit Frictions and the Macroeconomy, LAEF Business CYCLES Conference, LSE Macro Workshop, SAET Meetings (Paris), Sheffield Macro Workshop, NIESR/ESRC The Future of Housing Finance Conference, UBC Summer Finance Conference, the Bank of Canada Monetary Policy and Financial Stability Conference, Housing and the Economy Conference in Berlin, SED (Warsaw), the 2015 MOVE Barcelona Macro Workshop, Monetary Policy and the Distribution of Income and Wealth Conference in St. -

Petr Sedlácek

Petr Sedl´aˇcek September, 2021 Website: http://users.ox.ac.uk/∼econ0506 University of New South Wales Email: [email protected] School of Economics [email protected] Business School Building Sydney, NSW 2052, Australia Current Affiliations 2021 - Professor of Economics, University of New South Wales 2019 - Professor of Economics, University of Oxford 2015 - Research Affiliate, Center for Economic Policy Research Previous Affiliations 2017 - 2021 Editorial Board Member, Oxford Economic Papers 2017 - 2021 Tutorial Fellow in Economics, Christ Church 2017 - 2019 Associate Professor, University of Oxford 2016 - 2017 Visiting scholar, Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco and UC Berkeley 2014 - 2017 Researcher, Hausdorff Center for Mathematics 2012 - 2017 Assistant (Junior) Professor, Universit¨atBonn 2011 - 2012 Postdoctoral researcher, University of Amsterdam 2011 Visiting PhD student, European Central Bank 2005 - 2006 Research assistant, Czech Statistical Office Education 2011 Ph.D. in Economics advisor: Wouter J. den Haan, Universiteit van Amsterdam 2008 M.Phil. in Econometrics and Macroeconomics (Cum Laude) Tinbergen Institute, Amsterdam 2007 Ing. in Economic Policy and Macroeconomic Analysis (Msc equivalent) Prague University of Economics 2005 M.A. in Economics (with Distinction) Joint European Studies Program Publications "The Macroeconomic Impact of Trump", with Benjamin Born, Gernot Mueller and Moritz Schularick, Policy Studies, 2021. "The Nature of Firm Growth", with Benjamin Pugsley and Vincent Sterk, American Economic Review, vol. 111 (2), 2021. "Startups and Employment Following the COVID Pandemic: A Calculator", with Vincent Sterk, COVID Economics, vol. 13, 2020. "Lost Generations of Firms and Aggregate Labor Market Dynamics", Journal of Monetary Economics, vol 111, 2020. "The Economic Consequences of the Brexit Vote", with Benjamin Born, Gernot Mueller and Moritz Schularick, The Economic Journal, vol. -

Vincent Sterk May, 2021 Contact Information

Vincent Sterk May, 2021 Contact Information University College London Department of Economics Drayton House, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, United Kingdom phone: +44 207 679 5877 e-mail: [email protected] personal website: www.homepages.ucl.ac.uk/~uctpvst/ Employment and academic affiliations 2020– Review of Economic Dynamics, associate editor 2018- University College London, associate professor of economics (since October) 2018– Review of Economic Studies, editorial board member 2018– Journal of the European Economic Association, associate editor 2017– Economic Journal, associate editor 2016– Centre for Economic Policy Research, research affiliate 2012 – Centre for Macroeconomics, member 2011 – 2018 University College London, lecturer in Economics 2007 – 2011 De Nederlandsche Bank, economist Policy consultancy 2018– Bank of England, academic consultant 2020– European Commission, consultancy project on startups and Covid-19. Education 2007 – 2011 University of Amsterdam PhD in Economics (cum laude) Thesis title: “The Role of Mortgages and Consumer Credit in the Business Cycle” 2000 - 2005 Tilburg University BSc and MSc in Econometrics and Operations Research Research Interests Business Cycles, Monetary Policy, Firm Dynamics, Startups, Labor Markets, Inequality Publications Refereed articles: “Quantitative Easing with Heterogeneous Agents”, with Wei Cui (2018). CEPR DP13322. Forthcoming, Journal of Monetary Economics. “The Nature of Firm Growth”, with ® Petr Sedlacek (2021) ® Ben Pugsley American Economic Review. Vol 111 (2), 547-579. “Macroeconomic Fluctuations with HANK and SAM: an Analytical Approach”, with Morten O. Ravn (2020). Forthcoming in the Journal of the European Economic Association. Available 1 as CEPR DP 11696. “Reviving American Entrepreneurship? Tax Reform and Business Dynamism (2019)”, with Petr Sedlacek, Journal of Monetary Economics, Volume 105, Pp. -

Unemployment Crises

Unemployment Crises Nicolas Petrosky-Nadeau∗ Lu Zhang† FRB San Franciso Ohio State and NBER December 2018‡ Abstract A search model of equilibrium unemployment, calibrated to the postwar sample, poten- tially explains the unemployment crisis in the Great Depression. The limited responses of wages from credible bargaining to aggregate conditions, along with matching frictions, cause the unemployment rates to rise sharply in recessions but to decline only gradu- ally in booms. The frequency and severity of the crises in the model are quantitatively consistent with U.S. historical data. However, when we feed the measured labor produc- tivity into the model, its unemployment crisis is less persistent than that in the 1930s. JEL Classification: E24, E32, J63, J64. Keywords: Search and matching, unemployment crises, the Great Depression, the un- employment volatility, nonlinear impulse response functions ∗Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, 101 Market Street, San Francisco CA 94105. Tel: (415) 974-2740. E-mail: [email protected]. †Fisher College of Business, The Ohio State University, 760A Fisher Hall, 2100 Neil Avenue, Columbus OH 43210; and NBER. Tel: (614) 292-8644. E-mail: zhanglu@fisher.osu.edu. ‡We are grateful to Hang Bai, Andrew Chen, Daniele Coen-Pirani, Steven Davis, Mariacristina De Nardi, Paul Evans, Wouter Den Haan, Bob Hall, Dale Mortensen, Morten Ravn, Paulina Restrepo-Echavarria, Robert Shimer, Etienne Wasmer, Randall Wright, Rafael Lopez de Melo, and other seminar participants at Federal Reserve Bank of San -

Tarik Sezgin Ocaktan

TARIK SEZGIN OCAKTAN ÙÖÖÒØ ÈÓ×ØÓÒ • PhD candidate at the Université Panthéon-Sorbonne and Paris School of Economics, since September 2006. Research Topic: Unemployment Persistence over the Business Cycles and the Impact of Nonlinearities (Supervisor: Professor Michel Juillard). • Visiting PhD student at the Universiteit van Amsterdam under the supervision of Pro- fessor Wouter den Haan: September 2008 – February 2009 and May 2009. • Fellow of the Institute on Computational Economics 2008 at the University of Chicago: 27 July – 9 August 2008. • Université Catholique de Louvain, Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium – Master of Arts in Eco- nomics (2006). Master thesis: "Decomposing Real GDP into Stochastic Trend and Transi- tory Components using State Space models" – 2006. Supervisor: Professor L. Bauwens. • Université Louis Pasteur, Strasbourg, France – Maitrise et licence en Econométrie (2001). Master thesis: "Relation between Expenditures in R&D and Productivity - An Economet- ric Analysis with Panel Data" (in french) – 2001. Supervisor: Professor J. El Ouardighi (member of the jury: Professor M. Sidiropoulos). • "Méthodes de simulation des modèles stochastiques d’équilibre général" (with Michel Juillard). Economie et Prévision (Numéro Spécial). 2008/2-3. ÏÓÖÒ ÈÔ Ö • "Solving Dynamic Models with Heterogeneous Agents and Aggregate Uncertainty with Dynare or Dynare++" (with Wouter den Haan). in preparation Ó ÓÑÑ • "Solving Dynamic Models with Heterogeneous Agents and Aggregate Uncertainty with Dynare or Dynare++" – 64th European Meeting of the Econometric Society – Barcelona, August 2009 (paper accepted) • 15th international Conference of Computing in Economics and Finance – Sydney, July 2009 (paper accepted) • Annual Meeting of the Society for Economic Dynamics – Istanbul, July 2009 (paper ac- cepted) • "Unemployment Persistence in a DSGE Model with Search and Matching Theory: The Impact of the Accuracy of Numerical Approximation on Estimation" – May 2007. -

Odyssean Forward Guidance in Monetary Policy: a Primer

Odyssean forward guidance in monetary policy: A primer Jeffrey R. Campbell Introduction and summary with making its internal decision-making process The Federal Open Market Committee’s (FOMC) more transparent and therefore more forecastable. In monetary policy statement from its September 2013 this, they followed several foreign central banks that meeting reads in part: had already adopted explicit inflation targets. (See Bernanke and Woodford, 2005, for a review of inflation In particular, the Committee decided to keep targeting and its implementation outside the United the target range for the federal funds rate at 0 to States.) The financial crisis dramatically accelerated 1/4 percent and currently anticipates that this ex- the transition to greater openness, and the FOMC’s ceptionally low range for the federal funds rate will be appropriate at least as long as the unem- ployment rate remains above 6-1/2 percent, infla- Jeffrey R. Campbell is a senior economist and research advisor tion between one and two years ahead is projected in the Economic Research Department at the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago and an external fellow at CentER, Tilburg to be no more than a half percentage point above University. The author is grateful to Marco Bassetto, Charlie the Committee’s 2 percent longer-run goal, and Evans, Jonas Fisher, Alejandro Justiniano, and Spencer Krane for many stimulating discussions on forward guidance and to longer-term inflation expectations continue to be Wouter den Haan, Alejandro Justiniano, and Dick Porter for well anchored.1 helpful editorial feedback. This article is being concurrently published in Wouter den Haan (ed.), 2013, Forward Guidance— This extended reference to the conditions deter- Perspectives from Central Bankers, Scholars and Market mining the FOMC’s future interest rate decisions is Participants, Centre for Economic Policy Research, VoxEU.org.