Full Issue 6.1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

5816 Hon. Irving M. Ives

5816 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD- HOUSE May 5 By Mr. POWELL: PETITIONS, ETC. teet the rights of States to prevent advertis H. R. 6085. A bill for the relief of Klaus ing withi:J?. their borders; to the Committee Under clause 1 of rule XXII, petitions on Interstate and Foreign Commerce. Samuli Gunnar Romppanen; to the Com and papers were laid on the Clerk's desk mittee on the Judiciary. 238. By Mr. McDOWELL: Petition pre· and referred as follows: sented by a group from the Woman's Chris By Mr. WALTER: tian Temperance Union of Delaware and H. R. 6086. A b111 for the relief of certain 237. By Mr. HORAN: Petition of 114 resi dents of the State of Washington to help residents of Wilmington, Del., protesting relatives of United States citizens or lawfully bring up mentally and morally sound chil the advertising of alcoholic beverages over resident aliens; to the Committee on the dren and to conquer the juvenile delin the radio and television and in magazines Judiciary. quency now in our midst by exercising the and newspapers, and urging support of Sen H. R. 6087. A bill for the relief of Salva powers of Congress to get alcoholic beverage ate bill 923, introduced by Senator LANGER tore Emmanuel Maltese; to the Committee advertising off the air and out of the chan in the 84th Congress; to the Committee on on the Judiciary. nels of interstate commerce, and thus pro- Interstate and Foreign Commerce. EXTENSIONS OF REMARKS Commemoration of the Inauguration of Liberty, and to assert my strong support of of Commerce, the Sons of the American Rev pending legislation directed at adding to olution, the Downtown Manhattan Associa George Washington as First Presi their usefulness. -

The Forgotten Fronts the First World War Battlefield Guide: World War Battlefield First the the Forgotten Fronts Forgotten The

Ed 1 Nov 2016 1 Nov Ed The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The Forgotten Fronts The First Battlefield War World Guide: The Forgotten Fronts Creative Media Design ADR005472 Edition 1 November 2016 THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | i The First World War Battlefield Guide: Volume 2 The British Army Campaign Guide to the Forgotten Fronts of the First World War 1st Edition November 2016 Acknowledgement The publisher wishes to acknowledge the assistance of the following organisations in providing text, images, multimedia links and sketch maps for this volume: Defence Geographic Centre, Imperial War Museum, Army Historical Branch, Air Historical Branch, Army Records Society,National Portrait Gallery, Tank Museum, National Army Museum, Royal Green Jackets Museum,Shepard Trust, Royal Australian Navy, Australian Defence, Royal Artillery Historical Trust, National Archive, Canadian War Museum, National Archives of Canada, The Times, RAF Museum, Wikimedia Commons, USAF, US Library of Congress. The Cover Images Front Cover: (1) Wounded soldier of the 10th Battalion, Black Watch being carried out of a communication trench on the ‘Birdcage’ Line near Salonika, February 1916 © IWM; (2) The advance through Palestine and the Battle of Megiddo: A sergeant directs orders whilst standing on one of the wooden saddles of the Camel Transport Corps © IWM (3) Soldiers of the Royal Army Service Corps outside a Field Ambulance Station. © IWM Inside Front Cover: Helles Memorial, Gallipoli © Barbara Taylor Back Cover: ‘Blood Swept Lands and Seas of Red’ at the Tower of London © Julia Gavin ii | THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS THE FORGOTTEN FRONTS | iii ISBN: 978-1-874346-46-3 First published in November 2016 by Creative Media Designs, Army Headquarters, Andover. -

1••I Haras São Miguel

r L 1 :1 .4 1••I HARAS SÃO MIGUEL CAMPINAS - S. P. Proprietário: SR. ANTONIO ALVES DE MORAES 5/ 1 Pharos Nearo N.,ara Nasrulla h Blenhes m Mumtaz Begun Mumtaz Mahal [ CAMPANHA Truculentr Flag of Truce Respite I Conco dia A campanha dos 2 anos de Capitain Kidd foi bastante D,ophon expressiva, tendo vencido o "Stechworth Stakes" e o importante 1 Orama Cantelupe "National Breeders Procluce Stakes" (lb. 6.623) e colocando-se em 2.0 no "Gimcrack Stakes". CAPITUN KI1)D II Alazão - Inglaterra 1956 Aos 3 anos correu os "2.000 Guineus", tendo se colocado em Phalaris lugar, sendo depois vendido para os U.S.A. Prosseguindo sua Falrway Scapa Flow 5.0 campanha nesse Pais, ganhou 7 corridas, entre elas o "Fort Lau- Stephan the Great Blue Peter derdale Handicap" (sôbre Polylad e Petare. 1 milha e 1/16 em Fancy Free Celiba 102 s. e o "Broaclway Handicap" (Aqueduct. 1 milha e 1/16 em Hurry On J Marcovil 102. 8 a.) e colocando-se no "I{ollywood Premiere Handicap" Jy 1 Tout Suíte (Hollywood Park, ganho por Fleet Nasrullah) e no "Coronado Juniata í Junior Handicap" (Hollywood Park), totalizando USS 44.190. Samphre ALGUMAS REPRODUTORAS IMPORTADAS Branding IÂLY IRON LA PAT'l'I Enchanted Forest V.T(HF/R SuperlorI1 Solonaway BI( BÂMB()() CANI)ELl1'.' (.-1RN()R\I [ (IRCÊ 1 Selim Hassan 1)rPI'ElI Grie FIRF CHO' 4 Tucior Castle Citronade Desajiada 1 Foolish Falrel Propriedade de Revista Turf e Fomento Ltda. órgão Oficial das Comissões de Fomento e Turf do Jockey Club de São Paulo IniCliatíva ) Redator Responsável ANTERO DE CASTRO Já se disse que o Posto de Fomento Agropecuário do Jockey Club de São Paulo teria o seu lado negativo, repre- sentado pelo arrefecimento da iniciativa particular no setor das importações, çue provocaria como conseqüência de ofe- recer aos criadores os serviços de garanhões de primeira categoria. -

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory

Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory Edited by William E. Cain Professor of English Wellesley College A Routledge Series 94992-Humphries 1_24.indd 1 1/25/2006 4:42:08 PM Literary Criticism and Cultural Theory William E. Cain, General Editor Vital Contact Negotiating Copyright Downclassing Journeys in American Literature Authorship and the Discourse of from Herman Melville to Richard Wright Literary Property Rights in Patrick Chura Nineteenth-Century America Martin T. Buinicki Cosmopolitan Fictions Ethics, Politics, and Global Change in the “Foreign Bodies” Works of Kazuo Ishiguro, Michael Ondaatje, Trauma, Corporeality, and Textuality in Jamaica Kincaid, and J. M. Coetzee Contemporary American Culture Katherine Stanton Laura Di Prete Outsider Citizens Overheard Voices The Remaking of Postwar Identity in Wright, Address and Subjectivity in Postmodern Beauvoir, and Baldwin American Poetry Sarah Relyea Ann Keniston An Ethics of Becoming Museum Mediations Configurations of Feminine Subjectivity in Jane Reframing Ekphrasis in Contemporary Austen, Charlotte Brontë, and George Eliot American Poetry Sonjeong Cho Barbara K. Fischer Narrative Desire and Historical The Politics of Melancholy from Reparations Spenser to Milton A. S. Byatt, Ian McEwan, Salman Rushdie Adam H. Kitzes Tim S. Gauthier Urban Revelations Nihilism and the Sublime Postmodern Images of Ruin in the American City, The (Hi)Story of a Difficult Relationship from 1790–1860 Romanticism to Postmodernism Donald J. McNutt Will Slocombe Postmodernism and Its Others Depression Glass The Fiction of Ishmael Reed, Kathy Acker, Documentary Photography and the Medium and Don DeLillo of the Camera Eye in Charles Reznikoff, Jeffrey Ebbesen George Oppen, and William Carlos Williams Monique Claire Vescia Different Dispatches Journalism in American Modernist Prose Fatal News David T. -

NP 2013.Docx

LISTE INTERNATIONALE DES NOMS PROTÉGÉS (également disponible sur notre Site Internet : www.IFHAonline.org) INTERNATIONAL LIST OF PROTECTED NAMES (also available on our Web site : www.IFHAonline.org) Fédération Internationale des Autorités Hippiques de Courses au Galop International Federation of Horseracing Authorities 15/04/13 46 place Abel Gance, 92100 Boulogne, France Tel : + 33 1 49 10 20 15 ; Fax : + 33 1 47 61 93 32 E-mail : [email protected] Internet : www.IFHAonline.org La liste des Noms Protégés comprend les noms : The list of Protected Names includes the names of : F Avant 1996, des chevaux qui ont une renommée F Prior 1996, the horses who are internationally internationale, soit comme principaux renowned, either as main stallions and reproducteurs ou comme champions en courses broodmares or as champions in racing (flat or (en plat et en obstacles), jump) F de 1996 à 2004, des gagnants des neuf grandes F from 1996 to 2004, the winners of the nine épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Japan Cup, Melbourne Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Queen Elizabeth II Stakes (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F à partir de 2005, des gagnants des onze grandes F since 2005, the winners of the eleven famous épreuves internationales suivantes : following international races : Gran Premio Carlos Pellegrini, Grande Premio Brazil (Amérique du Sud/South America) Cox Plate (2005), Melbourne Cup (à partir de 2006 / from 2006 onwards), Dubai World Cup, Hong Kong Cup, Japan Cup (Asie/Asia) Prix de l’Arc de Triomphe, King George VI and Queen Elizabeth Stakes, Irish Champion (Europe/Europa) Breeders’ Cup Classic, Breeders’ Cup Turf (Amérique du Nord/North America) F des principaux reproducteurs, inscrits à la F the main stallions and broodmares, registered demande du Comité International des Stud on request of the International Stud Book Books. -

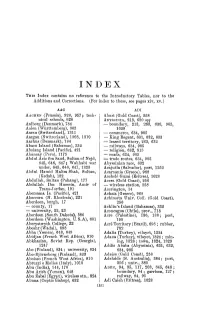

For Index to These, See Pages Xiv, Xv.)

INDEX THis Index contains no reference to the Introductory Tables, nor to the Additions and Corrections. (For index to these, see pages xiv, xv.) AAC ADI AAcHEN (Prussia), 926, 957; tech- Aburi (Gold Coast), 258 nical schools, 928 ABYSSINIA, 213, 630 sqq Aalborg (Denmark), 784 - boundary, 213, 263, 630, 905, Aalen (Wiirttemberg), 965 1029 Aarau (Switzerland), 1311 - commerce, 634, 905 Aargau (Switzerland), 1308, 1310 - King Regent, 631, 632, 633 Aarhus (Denmark), 784 - leased territory, 263, 632 Abaco Island (Bahamas), 332 - railways, 634, 905 Abaiaug !Rland (Pacific), 421 - religion, 632, 815 Abancay (Peru), 1175 - roads, 634, 905 Abdul Aziz ibn Saud, Sultan of N ejd, -trade routes, 634, 905 645, 646, 647; Wahhabi war Abyssinian race, 632 under, 645, 646, 647, 1323 Acajutla (Salvador), port, 1252 Abdul Hamid Halim Shah, Sultan, Acarnania (Greece), 968 (Kedah), 182 Acchele Guzai (Eritrea), 1028 Abdullah, Sultan (Pahang), 177 Accra (Gold Coast), 256 Abdullah Ibn Hussein, Amir of - wireless station, 258 Trans-J orrlan, 191 Accrington, 14 Abemama Is. (Pacific), 421 Acha!a (Greece), 968 Abercorn (N. Rhodesia), 221 Achirnota Univ. Col!. (Gold Coast), Aberdeen, burgh, 17 256 - county, 17 Acklin's Island (Bahamas), 332 -university, 22, 23 Aconcagua (Chile), prov., 718 Aberdeen (South Dakota), 586 Acre (Palestine), 186, 188; port, Aberdeen (Washington, U.S.A), 601 190 Aberystwyth College, 22 Acre Territory (Brazil), 698 ; rubber, Abeshr (Wadai), 898 702 Abba (Yemen), 648, 649 Adalia (Turkey), vilayet, 1324 Abidjan (French West Africa), 910 Adana (Turkey), vilayet, 1324; min Abkhasian, Soviet Rep. (Georgia), ing, 1328; town, 1324, 1329 1247 Addis Ababa (Abyssinia), 631, 632, Abo (Finland), 834; university, 834 634, 905 Abo-Bjorneborg (Finland), 833 Adeiso (Gold Coast), 258 Aboisso (French West Africa), 910 Adelaide (S. -

DRAWING the COLOR LINE, by Howard Zinn

"Columbus, The Indians, and Human Progress" - Chapter 1 from Howard Zinn's A People's History of the United States : 1492 - Present, Revised and Updated Edition, (New York: HarperCollins, 1995) - by permission Arawak men and women, naked, tawny, and full of wonder, emerged from their villages onto the island's beaches and swam out to get a closer look at the strange big boat. When Columbus and his sailors came ashore, carrying swords, speaking oddly, the Arawaks ran to greet them, brought them food, water, gifts. He later wrote of this in his log: They...brought us parrots and balls of cotton and spears and many other things, which they exchanged for the glass beads and hawks' bells. They willingly traded everything they owned...They were well-built, with good bodies and handsome features....They do not bear arms, and do not know them, for I showed them a sword, they took it by the edge and cut themselves out of ignorance. They have no iron. Their spears are made of cane...They would make fine servants....With fifty men we could subjugate them all and make them do whatever we want. These Arawaks of the Bahama Islands were much like Indians on the mainland, who were remarkable (European observers were to say again and again) for their hospitality, their belief in sharing. These traits did not stand out in the Europe of the Renaissance, dominated as it was by the religion of popes, the government of kings, the frenzy for money that maked Western civilization and its first messenger to the Americas, Christopher Columbus. -

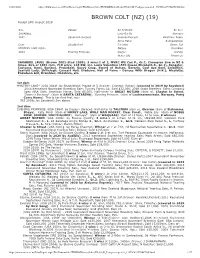

BROWN COLT (NZ) (19) Foaled 24Th August 2019

16/01/2021 https://www.arion.co.nz/PrintReport.aspx?FileName=/files/TDN/00MysteryLake(USA)190_Pedigreesreport-0_132552621578887298.html BROWN COLT (NZ) (19) Foaled 24th August 2019 Sire Zabeel Sir Tristram Sir Ivor SAVABEEL Lady Giselle Nureyev 2001 Savannah Success Success Express Hold Your Peace Alma Mater Semipalatinsk Dam Shackleford Forestry Storm Cat MYSTERY LAKE (USA) Oatsee Unbridled 2014 Evening Primrose Dayjur Danzig Water Lily Riverman SAVABEEL (AUS) (Brown 2001-Stud 2005). 3 wins-1 at 2, MVRC WS Cox P., Gr.1. Champion Sire in NZ 6 times. Sire of 1001 rnrs, 710 wnrs, 110 SW, inc. Lucia Valentina (ATC Queen Elizabeth S., Gr.1), Sangster, Costume, Kawi, Soriano, Probabeel, Savvy Coup, Sword of Osman, Savaria, Cool Aza Beel, Embellish, Scarlett Lady, Shillelagh, Concert Hall, Diademe, Hall of Fame - Dances With Dragon (H.K.), Nicoletta, Pasadena Girl, Brambles, Hasahalo, etc. 1st dam MYSTERY LAKE* (USA 2014f. by Shackleford) Placed at 3 (trainer: Crichton, Rohan).(covered in 2019 by Savabeel) .2014 Keeneland November Breeding Sale; Turnley Farms LA; Sold $32,000. 2016 Ocala Breeders' Sales Company Open HRA Sale; American Horse; Sold $5,000. Half-sister to GREAT NOTION (dam o), Chester le Street, Discreet Evening* (dam of SANTA CATARINA), Evening Princess (dam of Lookinatamiracle, Norquay, Patty Come Home). This is her first foal, inc:- (NZ 2019c. by Savabeel) See above. 2nd dam EVENING PRIMROSE (USA 1994f. by Dayjur) Unraced. Half-sister to TALINUM (dam o), Gharam (dam of Elshamms, Shaya), Kelly Pond (dam of HONEY LAKE, WOLF MAN ROCKET, Clear Pond), Noble Lily (dam of NOBLE ROSE, SIMEON, NOCTILUCENT), Hamaya* (dam of WAQUAAS). -

![An Atlas of Antient [I.E. Ancient] Geography](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8605/an-atlas-of-antient-i-e-ancient-geography-1938605.webp)

An Atlas of Antient [I.E. Ancient] Geography

'V»V\ 'X/'N^X^fX -V JV^V-V JV or A?/rfn!JyJ &EO&!AElcr K T \ ^JSlS LIBRARY OF WELLES LEY COLLEGE PRESENTED BY Ruth Campbell '27 V Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2011 with funding from Boston Library Consortium Member Libraries http://www.archive.org/details/atlasofantientieOObutl AN ATLAS OP ANTIENT GEOGRAPHY BY SAMUEL BUTLER, D.D. AUTHOR OF MODERN AND ANTJENT GEOGRAPHY FOR THE USE OF SCHOOLS. STEREOTYPED BY J. HOWE. PHILADELPHIA: BLANQHARD AND LEA. 1851. G- PREFATORY NOTE INDEX OF DR. BUTLER'S ANTIENT ATLAS. It is to be observed in this Index, which is made for the sake of complete and easy refer- ence to the Maps, that the Latitude and Longitude of Rivers, and names of Countries, are given from the points where their names happen to be written in the Map, and not from any- remarkable point, such as their source or embouchure. The same River, Mountain, or City &c, occurs in different Maps, but is only mentioned once in the Index, except very large Rivers, the names of which are sometimes repeated in the Maps of the different countries to which they belong. The quantity of the places mentioned has been ascertained, as far as was in the Author's power, with great labor, by reference to the actual authorities, either Greek prose writers, (who often, by the help of a long vowel, a diphthong, or even an accent, afford a clue to this,) or to the Greek and Latin poets, without at all trusting to the attempts at marking the quantity in more recent works, experience having shown that they are extremely erroneous. -

A Critical Review of Jeremy Brecher's Strike!

Summary: The new expanded edition of Brecher’s Strike! is a monumental contribution to labor history. This review discusses the book’s revolutionary qualities, while also questioning its treatment of the IWW and most importantly, of the intersectionality of race and class - Editors A Critical Review of Jeremy Brecher’s Strike! Dale Heckerman May 28, 2016 In the field of radical labor history, Jeremy Brecher’s Strike! is held in high esteem by fellow leftists and labor historians and is considered one of the standard go-to reference books for anyone aspiring to learn labor history. I agree that this book is a must-read source of information on labor’s struggles in the United States during the period from 1877 to today. I believe that Jeremy Brecher genuinely cares about the plight of the working class as he painstakingly details numerous labor actions over the past, nearly one-hundred-forty years of labor history. I learned a lot from this book and it would be very difficult to sum up all the various strikes and labor actions he covers. I recommend that everyone read it for the wealth of information and insight this book contains. We learn a lot from Brecher concerning the creativity and co-operation between workers that has been hidden from “conventional” history. A critical examination of the history of unions and union leaders is taken up, as well, which ranges from the heroic, e.g., Mary Harris Jones (Mother Jones), to the development of parasitic business unionism. Brecher begins his book by briefly discussing the fact that strikes occurred during the building of the Great Pyramids of Egypt and that strikes had occurred International Marxist-Humanist Organization Email: [email protected] Web: www.internationalmarxisthumanist.org as early as 1636 in North America, where the strikers were prosecuted as illegal conspirators. -

Resisting Neoliberal Globalization: Coalition Building Between

RESISTING NEOLIBERAL GLOBALIZATION: COALITION BUILDING BETWEEN ANTI-GLOBALIZATION ACTIVISTS IN NORTHWEST OHIO Kendel A. Kissinger A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF ARTS December 2005 Committee: Rekha Mirchandani, Advisor Philip Terrie ii ABSTRACT Rekha Mirchandani, Advisor Few scholars have attempted to document the nature of coalition building within the antiglobalization movement, and this study is an attempt to analyze part of this complex and important social movement. This study is a synopsis of Northwest Ohio’s anti-globalization movement and concentrates on the nature of alliances across movements and the numerous dilemmas they encounter. The major assumption of this project is that neoliberalism dominates the globalization process through the policies and practices of various governance institutions and that the anti-globalization movement arose as a counter-movement in response to neoliberal changes. Based on thirteen interviews conducted within Northwest Ohio’s activist community, this study is a qualitative research project that explores the motivations of labor, peace, farm worker, environmental, and anarchist activists, their concerns about the nature of globalization, and their experiences with cross-movement alliance building. The objective of this study is, first, to provide some historical context on globalization, political and economic thought, coalition building, anti-globalization’s antecedent movements and the broader national and international movement; second, to explain how and why various social movements in Northwest Ohio became part of the anti-globalization movement and identify the problematic issues of cross-movement alliances. The study begins with a review of literature on coalitional movements, anti-globalization activism, and the antecedent movements of Northwest Ohio’s anti-globalization movement. -

Cyber-Marx.Pdf

iii Acknowledgements Brecht somewhere remarks that “the formation of intellectuals is a long and difficult process, and sorely tries the patience of the masses.” This book began as a doctoral dissertation, and its writing has thus been an integral part of my formation as an intellectual. The process has undoubtedly tried the patience of many individuals and collectives, who have, nevertheless, unstintingly contributed to it. Foremost amongst these is Rick Gruneau, who, as my doctoral supervisor, allowed me the latitude to follow my interests, offered insightful criticism, and had the generosity of spirit to support a dissertation some of whose specific arguments he disagreed with. Other faculty members at Simon Fraser University also strongly influenced the project, without bearing responsibility for its outcome. Chin Bannerjee’s course on Lukacs, interrupted as it was by a campus strike, set the political ball rolling a long time ago. Michael Lebowitz’s profound lectures on Capital and Grundrisse showed me what Marxism could, and should, be. Two great teachers now, alas, gone to glory, deeply marked my thinking about the issues discussed here. Margaret Benston introduced me to cyberspace, but, much more importantly, gave me an enduring example of warmth and intelligence on the left before her tragically early death. Dallas Smythe, whose writings I had long admired, did me the honour of reading a draft chapter and discussing it one memorable afternoon very shortly before he passed away. If these pages contain anything worthy of such mentors, scholars and revolutionaries both, then I regard the writing time as well spent. My friends and fellow doctoral students Dorothy Kidd and Santiago Valles played a very special role in the production of this book.