Christo Interview-Edited

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Art / Earthworks Robert Smithson (US, 1938-1973) Spiral Jetty, 1970, Great Salt Lake, Black Rocks, Salt Crystals, Dia Foundation Collection

Land Art / Earthworks Robert Smithson (US, 1938-1973) Spiral Jetty, 1970, Great Salt Lake, black rocks, salt crystals, Dia foundation collection Robert Smithson (left) and Donald Judd (right) at site of Spiral Jetty, 1970 Minimalism – Post-Minimalism Nancy Holt (US b. 1938, environmental artist) Sun Tunnels, exterior and interior view (Sunset on the Summer Solstice), 1973-76 Robert Smithson, Floating Island to Travel Around Manhattan Island (1970/2005) 30-x-90- foot barge landscaped with earth, rocks, and native trees and shrubs, towed by a tugboat around the island of Manhattan, produced by Minetta Brook in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art during Smithson’s 2005 retrospective. (right) Smithson, Study for Floating Island, 1970. pencil on paper. 19″ x 24″ Dénes Ágnes: Izometrikus föld Nils Udo Richard Schilling Walter de Maria (US, b. 1935) Walter de Maria, The Lightning Field, 1974-77, near Quemado, New Mexico, 400 stainless steel poles, average height 20' 7 ½" Overall dimensions: 5,280 x 3,300' Andy Goldsworthy (Scottish, b.1956) Stone River, stone wall, Stanford University, 2004 Andy Goldsworthy’s global Cairns Cairn with clay wall, London - temporary Roof of NYC Metropolitan MA - temporary La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art - permanent Andy Goldsworthy, Woven bamboo, windy..., Before the Mirror, 1987, photograph Goldsworthy’s photographs of art made on his walks in nature of stones, berries, leaves http://youtu.be/YkHRZQU6bjI Excerpt from a highly recommended film on Goldsworthy’s art: Rivers and Tides, DVD 000134 available in the Sac State library. You can get extra credit for watching it. Christo Javacheff, (Bulgarian-American, b.1935), (top left) Package on Wheelbarrow, 1963, Paris, New Realist Christo & Jeanne Claude (French, b. -

Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design Summer 8-12-2014 Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple Candice M. Greathouse Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Greathouse, Candice M., "Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/168 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER AND THE COLLABORATIVE ARTIST COUPLE by CANDICE GREATHOUSE Under the Direction of Dr. Susan Richmond ABSTRACT Through description and analysis of the balancing and intersection of gender in the col- laborative artist couples of Marina Abramović and Ulay, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, and Chris- to and Jeanne-Claude, I make evident the separation between their public lives and their pri- vate lives, an element that manifests itself in unique and contrasting ways for each couple. I study the link between gendered negotiations in these heterosexual artist couples and this divi- sion, and correlate this relationship to the evidence of problematic gender dynamics in the art- works and collaborations. INDEX WORDS: -

Presentation for Christo and Jeanne Claude

Presentation for Christo and Jeanne Claude I Slide 1 A fun idea: You may want to wrap an object or package before the presentation. You can wrap it in plain fabric, white paper or colored wrapping paper. Make a big show of it and put it in a conspicuous place when you walk into the room on the day of the presentation. Do not mention it or refer to it. Do the students seem curious? How long before someone asks about it? Is the fact that they do not know what is inside intriguing? Does it make the object more interesting? As most of you know, in Art in the Classroom we look at art and discuss works of art. What is art to you? Let the children give their ideas. Some definitions you might suggest: Expression of what is beautiful Use of skill and creative imagination Art is something out of the ordinary, always incorporating new ideas and techniques. If it wasn’t, wouldn’t it be boring? Slide 2 Show Mona Lisa, Monet’s Bridge at Argentueil and “Yellow Store Front” by Christo Which of these is art? Let the children voice their ideas. What if I told you that they are all art? Today we are going on a trip around the world to look at a pair of artists that do very creative work on a very large scale. They transform the ordinary into something that makes people stop and look at things in a different way. Slide 3 Show “Wrapped bottles and cans” and “wrapped object” Can anyone tell me what these objects are? Is this how you normally see them? What is your initial reaction to it? What could be in the package on the right? Does it make you think and wonder? Why would an artist want to express themselves by wrapping or covering something? What comment would they be making? When we look at art, some of the tools we use to talk about it are the Elements of Art: Color, light, line, shape, texture and space (composition). -

The Tom Golden Collection

The Tom Golden Collection 2001.51.1 “Running Fence‐‐Project for Sonoma and Marin Counties." Artist: Christo, 1974. Original drawing collage for Running Fence project. Signed: "CHRISTO, 1974", (lower left above title). L 28 x W 22. 2001.51.2 “Wrapped Walk Ways‐‐Project for Loose Park, Kansas City, Missouri." Artist: Christo, 1978. Original collages photograph by Wolfgang Volz. Signed: "CHRISTO, 1978" (Right 2001.51.3.1 “Surrounded Islands‐‐Project for Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida." Artist: Christo, 1983. Collage with fabric, pastel, charcoal, pencil, crayon, enamel paint, fabric sample, and aerial photograph. TWO PARTS (A‐B). Signed: "CHRISTO, 1983" (lower right 2001.51.3.2 “Surrounded Island Project for Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida." Artist: Christo, 1983. Collage with fabric, pastel, charcoal, pencil, crayon, enamel paint, fabric sample, and aerial photography. Two of two parts. Signed: "CHRISTO 1983" (lower right on sample fabric.) 2001.51.4 “The Pont Neuf, Wrapped‐‐Project for Paris." Artist: Christo, 1979. Collages photograph (pencil, enamel paint, crayon, charcoal, and photograph by Wolfgang Volz on paper). Signed: "CHRISTO, 1979" (Lower left). 2001.51.5 "For Tom Sept, 1985 Paris." Original instructional ink sketch is of a lamp post of Christo and Jeanne‐Claude, The Pont Neuf, Wrapped (Project for Paris). Artist: Christo, 1985. Signed across the bottom "For Tom Sept, 1985 Paris CHRISTO." 2001.51.6 "For Tom, With Love, Many Thanks." Artist: Christo, 1985. Original sketch was done to show how four barrel sculptures were to be reassembled in Basel, Switzerland and be photographed for documentation by Eeva‐Enkeri for Christo and Jeanne‐Claude. -

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Gabrovo, 1942 Christo (left) and his two brothers Stefan (center) and Anani (right) Photo: Vladimir Yavachev © 1942 Christo 1935 Christo: American, Bulgarian-born Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, June 13, 1935, Gabrovo, of a Bulgarian industrialist family. Jeanne-Claude: American, French-born Jeanne-Claude Marie Denat, June 13, 1935, Casablanca, of a French military family, educated in France and Switzerland. Died November 18, 2009, New York City. 1952 Jeanne-Claude: Baccalauréat in Latin and Philosophy, University of Tunis, Tunisia. 1953-56 Christo: Studies at the National Academy of Art, Sofia, Bulgaria. Gabrovo, 1949 Christo (left) during a drawing lesson Photo: Archive © 1949 Christo 1956 In fall, Christo leaves Bulgaria to go to Prague, Czechoslovakia. 1957 On January 10, Christo escapes to Vienna, Austria, where he studies one semester at the Academy of Fine Arts. In October, he moves to Geneva, Switzerland. 1958 In March, Christo arrives in Paris, where he meets Jeanne-Claude in early October. Packages and Wrapped Objects. 1960 Birth of their son, Cyril, May 11. 1961 Project for a Wrapped Public Building. Stacked Oil Barrels and Dockside Packages, Cologne Harbor, 1961. Rolls of paper, oil barrels, tarpaulin and rope. Duration: two weeks. Christo and Jeanne-Claude's first collaboration. Paris, 1961 Christo in his studio at 14 rue de Saint-Senoch Photo: Jean-Jacques Lévèque 1962 Wall of Oil Barrels – The Iron Curtain, Rue Visconti, Paris, 1961-62. 89 barrels. Height: 13.7 feet (4.2 meters). Width: 13.2 feet (4 meters). Depth: 2.7 feet (0.5 meters). Duration: eight hours. Stacked Oil Barrels, Gentilly, near Paris, France. -

Christo and Jeanne-Claude: the Tom Golden Collection to Be Presenented at Biggs Museum

For Immediate Release Media Contact July 11, 2017 Stephanie Adams 302.674.2111 ext. 105 [email protected] CHRISTO AND JEANNE-CLAUDE: THE TOM GOLDEN COLLECTION TO BE PRESENENTED AT BIGGS MUSEUM Opening Reception on Friday, August 4th Dover, DE (July 11, 2017) - A traveling exhibition of a unique, rare collection of works of art by renowned artists Christo and Jeanne-Claude will visit the Biggs Museum of American Art from August 4 - October 22, 2017. 1 This blockbuster exhibition chronicles the career of husband and wife artistic team, Christo and Jeanne-Claude, well known for projects such as The Gates (Central Park, NYC, 2005) and Running Fence (Pictured Above - Sonoma and Marin Counties, California, 1976). The exhibition features extremely rare artworks that commemorate and celebrate the large-scale environmental installations undertaken by Christo and Jeanne- Claude for more than forty years. The collection includes original drawings, sculptures, collages and photographs capturing the versatility, longevity and international scope of the duo's extensive career. Charlie Guerin, Executive Director of the Biggs Museum, was fortunate to work with the couple in 1977 and is responsible for bringing this exhibition to Dover. "I met them while installing the Valley Curtain installation in Colorado and worked with them several times as they traveled exhibitions to museums around the country. I'm thrilled to see this exhibition come to our community," shares Charles Guerin. "People in our region may best remember the artists from The Gates installation in Central Park but their work has spanned the globe and it's a true honor to have some of it chronicled here at the Biggs." The collection that will be on view is one of the largest collections of art by Christo and Jeanne-Claude in the United States, and was started by Tom Golden in the summer of 1974. -

PRESS RELEASE CHRISTO and JEANNE-CLAUDE Reveal

PRESS RELEASE CHRISTO and JEANNE-CLAUDE reveal Location: 23 Bruton Street, second floor, London W1J 6QF, UK Champagne reception: Thursday June 28th, from 6pm to 8pm Exhibition dates: 21st June - 7th September, 2018 Opening times: Monday – Friday, 10am – 6 pm, Saturday by appointment Reveal is a retrospective exhibition of some of the most representative projects realised in a period of about 40 years by Christo and Jeanne-Claude. From 21st June to 7th September 2018 we will show fifteen artworks, among which Wrapped “Look” Magazine (1964), Kassel (1967), Wrapped trees (1969), Roman Wall (1974), Pont Neuf (1976), Mastaba (1977), Surrounded Islands (1983), Wrapped Reichstag (1986), Over the river (1995) and The Gates (2002). A champagne reception will be held on Thursday June 28th, from 6pm to 8pm. The great and ambitious works of Christo and Jeanne-Claude, their installations and their projects, were born in some way inspired by Man Ray’s masterpiece of 1920, L’enigme d’Isodore Ducasse – the first wrapping with a cover and some cord of an ordinary object (in this particular case a sewing machine) that history has memory of – and mainly teach us to re-learn to see, urging us to re-discover, to have new eyes. In ancient Greek, one of the most important words is «amazing», i.e. to be worthy of amazement, to be admirable. The philosopher, he who loves and seeks knowledge, is most of all a man who is amazed, a person who feels amazement also as fear, dizziness, and disorientation. And looking, observing, means understanding. It is good to notice that still today, I understand can be expressed with I see. -

Galeries Discussion

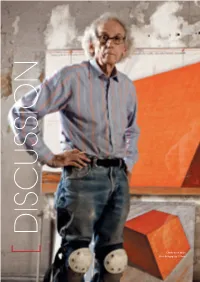

DISCUSSION GALERIES DISCUSSION Christo in his studio. [ Photo Wolfgang Volz. © Christo [ 24 ART MEDIA AGENCY – 26 JANuARY 2018 CHRISTO, INTIMATE AND MONUMENTAL Whilst the urban projects of Christo and Jeanne-Claude are on display at the ING Art Center, BRAFA is displaying a piece from the mid-1960s, Three Store Fronts. We look back on the history of this installation and look forward to the birth of Mastaba coming soon to Abu Dhabi, the largest sculpture in the world. Born in 1935 in Bulgaria, Christo Vladimiroff Javacheff, known as Christo, These pieces show the space that surround them. Could the worked with his wife and collaborator Jeanne-Claude Guillebon Denat, environment also be considered a subject of the piece? The process from the end of the 1950s until her death in 2009. Together, they have of seeing the space around the piece differently as a result of it? created many large-scale, on-site installations such as the packaging Our work has developed a lot through the idea of separating space, of the Pont-Neuf in Paris and the Reichstag in Berlin, or more recently controlling it and preventing the viewer from seeing what is happening the installation of over 7,000 panels of saffron-coloured cloth in Central on the other side. It’s about this idea of space as a barricade, something Park, New York and a foating bridge on Italy’s lake Iseo. Supporting I had already developed on Rue Visconti in 1961-1962, with Wall of Oil themselves fnancially through the sale of preparatory drawings, over the Barrels – The Iron Curtain. -

Christo Vladimirov Javacheff (1935

STATEMENT ON CHRISTO May 31, 2020 Artist Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, known as Christo, passed away of natural causes today, on May 31, 2020, at his home in New York City. He was 84 years old. Statement from Christo’s office: “Christo lived his life to the fullest, not only dreaming up what seemed impossible but realizing it. Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s artwork brought people together in shared experiences across the globe, and their work lives on in our hearts and memories. Christo and Jeanne-Claude have always made clear that their artworks in progress be continued after their deaths. Per Christo’s wishes, ‘L’Arc de Triomphe, Wrapped’ in Paris, France, is still on track for September 18 – October 3, 2021.” Christo was born on June 13, 1935 in Gabrovo, Bulgaria. He left Bulgaria in 1957, first to Prague, Czechoslovakia, and then escaped to Vienna, Austria, then moved to Geneva, Switzerland. In 1958, Christo went to Paris, where he met Jeanne-Claude Denat de Guillebon, not only his wife but life partner in the creation of monumental environmental works of art. Jeanne-Claude passed away on November 18, 2009. Christo lived in New York City for 56 years. From early wrapped objects to monumental outdoor projects, Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s artwork transcended the traditional bounds of painting, sculpture and architecture. Some of their work included Wrapped Coast, Little Bay in Sydney, Australia (1968-69), Valley Curtain in Colorado (1970–72), Running Fence in California (1972–76), Surrounded Islands in Miami (1980– 83), The Pont Neuf Wrapped in Paris (1975–85), The Umbrellas in Japan and California (1984– 91), Wrapped Reichstag in Berlin (1972–95), The Gates in New York’s Central Park (1979–2005), The Floating Piers at Italy's Lake Iseo (2014–16), and The London Mastaba on London’s Serpentine Lake (2016-18). -

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Kindle

CHRISTO AND JEANNE-CLAUDE PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Jacob Baal-Teshuva,Christo & Jeanne-claude,Wolfgang Volz | 96 pages | 15 Apr 2016 | Taschen GmbH | 9783836524094 | English | Cologne, Germany Christo and Jeanne-Claude PDF Book The Serdi Sardi , a Thracian tribe, established a settlement…. On the weekends, academy students were sent to paint propaganda and Christo unhappily participated. In the accessible interior of Big Air Package , the artist generated a unique experience of space, proportions, and light. Biography Christo and Jeanne-Claude were a collaborative artist duo known for their monumental environmental installations. Fineberg, Jonathan David Cengage Learning, January 23, November 1, Requires the attention of a conservator. The seller has recorded the following condition for this lot: The present work is in overall very good condition. One local rafting guide compared the project to "hanging pornography in a church. The fabric maintained the principal shapes of the Pont Neuf but it emphasized the details and the proportions. Articles from Britannica Encyclopedias for elementary and high school students. Christo and Jeanne Claude's first grand-scale urban project, wrapping the oldest bridge in Paris - the same bridge where Christo courted Jeanne-Claude. Professional and safe handling of packaging. In Cunningham Cameron, Alexandra ed. They originally worked under the name "Christo" to simplify dealings and their brand, [5] given the difficulties of establishing an artist's reputation and the prejudices against female artists, [6] but they would later retroactively credit their large-scale outdoor works to both "Christo and Jeanne-Claude". A love story set in the heart of Paris: bet And like every true artist, we create those works of art for us and our collaborators. -

Christo and Jeanne-Claude : Water Projects Pdf, Epub, Ebook

CHRISTO AND JEANNE-CLAUDE : WATER PROJECTS PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Germano Celant | 344 pages | 10 Oct 2018 | Silvana | 9788836633579 | English | Milan, Italy Christo and Jeanne-Claude : Water Projects PDF Book Tap here to turn on desktop notifications to get the news sent straight to you. Privacy Policy Cookie Notice Cookie list and settings Terms and Conditions WorldCat is the world's largest library catalog, helping you find library materials online. In the first movie, the artist explained how the giant London Mastaba installation was the culmination of over 60 years of working with stacked barrels. Following the passing of monumental artist Christo at the weekend, we delve into seven of his most significant projects realised in collaboration with his late partner Jeanne-Claude. Opprett en gratis konto. Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Featured: Documenta. Today the work exists only through documentation and memory. He also noted that they will finance the making of the piece themselves. The catalogue, besides a rich photographic section, includes an introductory text by Germano Celant and a dialogue between the curator and Christo. Drawing When planning the Surrounded Islands , the artists had to work with attorneys, marine biologists, engineers, marine engineers, mammal experts, and ornithologists. Thursday, January 21, Password Did you forgot your password? With over studies, drawings, collages, models and photographs from different collections, Curated by Germano Celant in collaboration with Christo and the CVJ Corporation. All rights reserved. Search WorldCat Find items in libraries near you. Subscribe to our newsletters. Water Projects presents a chronological display of the artists' works since the early Sixties. It is present in the artworks created by Rufino Tamayo and Frida Kahlo. -

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Water Projects Curated by Germano

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Water Projects Curated by Germano Celant Santa Giulia Museum Brescia April 7 – September 18, 2016 April 6, 2016 at the Santa Giulia Museum, Christo and Germano Celant, with Brescia’s Mayor Emilio Del Bono, Deputy-Mayor and Councilor for Culture Laura Castelletti, President of Fondazione Brescia Musei Massimo Minini and Director of Fondazione Brescia Musei Luigi Di Corato, will present the exhibition Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Water Projects, opening April 7. Set in the 2000 square meter spaces of Santa Giulia Museum, the show – curated by Celant in collaboration with the artist and his studio – will offer an unprecedented display of Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s water-related projects, that is those based on rural and urban landscapes characterized by the presence of water in the form of an ocean, a sea, a lake, or a river. With over 150 exhibits comprising the artists’ original preparatory studies, drawings and collages, complemented by scale-models, photos of the finished projects, videos, and films, inside the museum’s 2000 square meter exhibition space, Christo and Jeanne-Claude. Water Projects presents a chronological display of the artists’ monumental works since the early Sixties and illustrates their seven Water Projects, from Wrapped Coast, One Million Square Feet, Little Bay, Sydney, Australia, 1968-1969 to The Floating Piers, Project for Lake Iseo, Italy, 2014-16. The exhibition aims at presenting the projects within a historical framework, contextualizing their evolution, from 1961 to the present day, illustrating the artists’ water- related works in their different stages of realization, from the first concept sketches, to the drawings, collages and models that follow, all the way to the actual realization of the work documented in the form of photos and videos.