Public Art, Public Feeling: Contrasting Site-Specific Projects of Christo and Ai Weiwei

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Land Art / Earthworks Robert Smithson (US, 1938-1973) Spiral Jetty, 1970, Great Salt Lake, Black Rocks, Salt Crystals, Dia Foundation Collection

Land Art / Earthworks Robert Smithson (US, 1938-1973) Spiral Jetty, 1970, Great Salt Lake, black rocks, salt crystals, Dia foundation collection Robert Smithson (left) and Donald Judd (right) at site of Spiral Jetty, 1970 Minimalism – Post-Minimalism Nancy Holt (US b. 1938, environmental artist) Sun Tunnels, exterior and interior view (Sunset on the Summer Solstice), 1973-76 Robert Smithson, Floating Island to Travel Around Manhattan Island (1970/2005) 30-x-90- foot barge landscaped with earth, rocks, and native trees and shrubs, towed by a tugboat around the island of Manhattan, produced by Minetta Brook in collaboration with the Whitney Museum of American Art during Smithson’s 2005 retrospective. (right) Smithson, Study for Floating Island, 1970. pencil on paper. 19″ x 24″ Dénes Ágnes: Izometrikus föld Nils Udo Richard Schilling Walter de Maria (US, b. 1935) Walter de Maria, The Lightning Field, 1974-77, near Quemado, New Mexico, 400 stainless steel poles, average height 20' 7 ½" Overall dimensions: 5,280 x 3,300' Andy Goldsworthy (Scottish, b.1956) Stone River, stone wall, Stanford University, 2004 Andy Goldsworthy’s global Cairns Cairn with clay wall, London - temporary Roof of NYC Metropolitan MA - temporary La Jolla Museum of Contemporary Art - permanent Andy Goldsworthy, Woven bamboo, windy..., Before the Mirror, 1987, photograph Goldsworthy’s photographs of art made on his walks in nature of stones, berries, leaves http://youtu.be/YkHRZQU6bjI Excerpt from a highly recommended film on Goldsworthy’s art: Rivers and Tides, DVD 000134 available in the Sac State library. You can get extra credit for watching it. Christo Javacheff, (Bulgarian-American, b.1935), (top left) Package on Wheelbarrow, 1963, Paris, New Realist Christo & Jeanne Claude (French, b. -

Public Art Implementation Plan

City of Alexandria Office of the Arts & the Alexandria Commission for the Arts An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy Submitted by Todd W. Bressi / Urban Design • Place Planning • Public Art Meridith C. McKinley / Via Partnership Elisabeth Lardner / Lardner/Klein Landscape Architecture Table of Contents 1.0 Introduction 2.0 Vision, Mission, Goals 3.0 Creative Directions Time and Place Neighborhood Identity Urban and Natural Systems 4.0 Project Development CIP-related projects Public Art in Planning and Development Special Initiatives 5.0 Implementation: Policies and Plans Public Art Policy Public Art Implementation Plan Annual Workplan Public Art Project Plans Conservation Plan 6.0 Implementation: Processes How the City Commissions Public Art Artist Identification and Selection Processes Public Art in Private Development Public Art in Planning Processes Donations and Memorial Artworks Community Engagement Evaluation 7.0 Roles and Responsibilities Office of the Arts Commission for the Arts Public Art Workplan Task Force Public Art Project Task Force Art in Private Development Task Force City Council 8.0 Administration Staffing Funding Recruiting and Appointing Task Force Members Conservation and Inventory An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 2 Appendices A1 Summary Chart of Public Art Planning and Project Development Process A2 Summary Chart of Public Art in Private Development Process A3 Public Art Policy A4 Survey Findings and Analysis An Implementation Plan for Alexandria’s Public Art Policy 3 1.0 Introduction The City of Alexandria’s Public Art Policy, approved by the City Council in October 2012, was a milestone for public art in Alexandria. That policy, for the first time, established a framework for both the City and private developers to fund new public art projects. -

Public Art Toolkit

Aylesbury Vale Public Art Toolkit Who is this toolkit for? This toolkit can be used by anyone involved with making public art projects happen, however it has been developed to be specifically relevant to people commissioning art within a local authority context. What is public art? Public art has long been a feature of the public spaces across our towns and cities, with sculptures, paintings and murals often recalling historical characters or commemorating important events. Today, public art and artists are increasingly being placed at the centre of regeneration schemes as developers and local authorities recognise the benefits of integrating artworks into such programmes. Public art can include a variety of artistic approaches whereby artists or craftspeople work within the public realm in urban, rural or natural environments. Good public art seeks to integrate the creative skills of artists into the processes that shape the environments we live in. I see what you mean (2008), Lawrence Argent, University of Denver, USA For the Gentle Wind Doth Move Silently, Invisibly, (2006), Brian Tolle, Clevland, USA Spiral, Rick Kirby, (2004), South Woodham Ferres, Essex Animikii - Flies the Thunder, Anne Allardyce, (1992), Thunder Bay, Canada Types of Public Art approaches When thinking about future public art projects it is important to consider the full range of artistic approaches that could be used in a particular site, public art can be permanent or temporary; the following categories summarise popular approaches to public art. Sculpture Sculptural works are not solely about creating a precious piece of art but creating a piece which extends the sculpture into the wider landscape linking it with the environment and focussing attention on what is already there. -

SULZANO " Unending Dialogues Between Land and Islands" SULZANO GUIDE 3

TOURIST GUIDE SULZANO " unending dialogues between land and islands" SULZANO GUIDE 3 SULZANO BACKGROUND HISTORY much quicker and soon small Sulzano derives its name from workshops were turned into actual Sulcius or Saltius. It is located in an factories providing a great deal of area where there was once an ancient employment. Roman settlement and was born as a lake port for the area of Martignago. Along with the economic growth came wealth and during the Twentieth Once, the fishermen’s houses were century the town also became a dotted along the shore and around tourist centre with new hotels and the dock from where the boats would beach resorts. Many were the noble leave to bring the agricultural goods to and middle-class families, from the market at Iseo and the materials Brescia and also from other areas, from the stone quarry of Montecolo, who chose Sulzano as a much-loved used for the production of cement, holiday destination and readily built would transit through here directed elegant lake-front villas. towards the Camonica Valley. At the beginning of the XVI century, the parish was moved to Sulzano and thus the lake town became more important and bigger than the hillside Sulzano is a village that overlooks the one. During the XVII Century, many Brescia side of the Iseo Lake mills were built to make the most of COMUNE DI the driving force of the water that SULZANO flowed abundantly along the valley to the south of the parish. Via Cesare Battisti 91- Sulzano (Bs) Tel. 030/985141 - Fax. -

GREEN PAPER Page 1

AMERICANS FOR THE ARTS PUBLIC ART NETWORK COUNCIL: GREEN PAPER page 1 Why Public Art Matters Cities gain value through public art – cultural, social, and economic value. Public art is a distinguishing part of our public history and our evolving culture. It reflects and reveals our society, adds meaning to our cities and uniqueness to our communities. Public art humanizes the built environment and invigorates public spaces. It provides an intersection between past, present and future, between disciplines, and between ideas. Public art is freely accessible. Cultural Value and Community Identity American cities and towns aspire to be places where people want to live and want to visit. Having a particular community identity, especially in terms of what our towns look like, is becoming even more important in a world where everyplace tends to looks like everyplace else. Places with strong public art expressions break the trend of blandness and sameness, and give communities a stronger sense of place and identity. When we think about memorable places, we think about their icons – consider the St. Louis Arch, the totem poles of Vancouver, the heads at Easter Island. All of these were the work of creative people who captured the spirit and atmosphere of their cultural milieu. Absent public art, we would be absent our human identities. The Artist as Contributor to Cultural Value Public art brings artists and their creative vision into the civic decision making process. In addition the aesthetic benefits of having works of art in public places, artists can make valuable contributions when they are included in the mix of planners, engineers, designers, elected officials, and community stakeholders who are involved in planning public spaces and amenities. -

What Is Public Art?

POLICIES & PROCEDURES MANUAL Updated: February 2015 Contents INTRODUCTION .................................................................................................................................. 4 What is Public Art? ................................................................................................................................................................................. 4 CITY-FUNDED PUBLIC ART ............................................................................................................... 5 Summary of the Process .......................................................................................................................................................................... 5 Funding Policies ....................................................................................................................................................................................... 6 Funding Procedures ................................................................................................................................................................................. 6 Public Art Manager’s Role ..................................................................................................................................................................... 7 Generating Ideas for Public Art in Capital Projects............................................................................................................................. 8 Methods of Selecting Public Art .......................................................................................................................................................... -

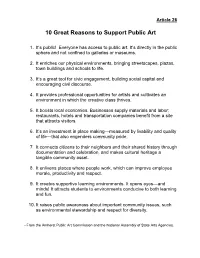

10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art

Article 26 10 Great Reasons to Support Public Art 1. It’s public! Everyone has access to public art. It’s directly in the public sphere and not confined to galleries or museums. 2. It enriches our physical environments, bringing streetscapes, plazas, town buildings and schools to life. 3. It’s a great tool for civic engagement, building social capital and encouraging civil discourse. 4. It provides professional opportunities for artists and cultivates an environment in which the creative class thrives. 5. It boosts local economies. Businesses supply materials and labor; restaurants, hotels and transportation companies benefit from a site that attracts visitors. 6. It’s an investment in place making—measured by livability and quality of life—that also engenders community pride. 7. It connects citizens to their neighbors and their shared history through documentation and celebration, and makes cultural heritage a tangible community asset. 8. It enlivens places where people work, which can improve employee morale, productivity and respect. 9. It creates supportive learning environments. It opens eyes—and minds! It attracts students to environments conducive to both learning and fun. 10. It raises public awareness about important community issues, such as environmental stewardship and respect for diversity. --From the Amherst Public Art Commission and the National Assembly of State Arts Agencies. The Amherst Public Art Commission Why Public Art for Amherst? Public art adds enormous value to the cultural, aesthetic and economic vitality of a community. It is now a well-accepted principle of urban design that public art contributes to a community’s identity, fosters community pride and a sense of belonging, and enhances the quality of life for its residents and visitors. -

Public Art Policy

CITY OF GILROY PUBLIC ART POLICY VISION STATEMENT: The City of Gilroy’s Public Art Committee promotes a bold vision which exemplifies the City’s creativity and energy shaping the visual environment of our community. PURPOSE: The City of Gilroy (City) recognizes the importance of Public Art to the cultural, educational and economic well-being of its diverse population. These guidelines are for the purpose of establishing policies and procedures for implementing Public Art as recommended in the Arts & Culture Commission’s Cultural Plan, developed in 1997, and 1999 General Plan Update. GOALS: To promote the City’s interest in its aesthetic environment. To establish the Public Art Committee as an advisory committee to the Arts and Culture Commission to be responsible for developing the Public Art Plan; ensuring the quality of artworks created under the plan; and, developing budgets, funding strategies and scope of individual Public Art projects. To create an enhanced visual environment within the City and provide City residents with the opportunity to live with Public Art. To help build pride in our City and among its citizens. To promote tourism and economic vitality of the City by enhancing the City’s public facilities and surroundings through the incorporation of Public Art. To encourage creative collaboration among community members. To encourage the creation of quality Public Art throughout the City by promoting locally, regionally, nationally and internationally recognized artists. To educate, preserve, reflect and celebrate the rich, unique history and cultural diversity of the City and its citizens. To promote and encourage art viewed by the public in all of the City’s communities and neighborhoods and to support the residents’ involvement in determining the character of their City. -

Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University Art and Design Theses Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design Summer 8-12-2014 Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple Candice M. Greathouse Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses Recommended Citation Greathouse, Candice M., "Gender and the Collaborative Artist Couple." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2014. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/art_design_theses/168 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Ernest G. Welch School of Art and Design at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in Art and Design Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. GENDER AND THE COLLABORATIVE ARTIST COUPLE by CANDICE GREATHOUSE Under the Direction of Dr. Susan Richmond ABSTRACT Through description and analysis of the balancing and intersection of gender in the col- laborative artist couples of Marina Abramović and Ulay, John Lennon and Yoko Ono, and Chris- to and Jeanne-Claude, I make evident the separation between their public lives and their pri- vate lives, an element that manifests itself in unique and contrasting ways for each couple. I study the link between gendered negotiations in these heterosexual artist couples and this divi- sion, and correlate this relationship to the evidence of problematic gender dynamics in the art- works and collaborations. INDEX WORDS: -

Presentation for Christo and Jeanne Claude

Presentation for Christo and Jeanne Claude I Slide 1 A fun idea: You may want to wrap an object or package before the presentation. You can wrap it in plain fabric, white paper or colored wrapping paper. Make a big show of it and put it in a conspicuous place when you walk into the room on the day of the presentation. Do not mention it or refer to it. Do the students seem curious? How long before someone asks about it? Is the fact that they do not know what is inside intriguing? Does it make the object more interesting? As most of you know, in Art in the Classroom we look at art and discuss works of art. What is art to you? Let the children give their ideas. Some definitions you might suggest: Expression of what is beautiful Use of skill and creative imagination Art is something out of the ordinary, always incorporating new ideas and techniques. If it wasn’t, wouldn’t it be boring? Slide 2 Show Mona Lisa, Monet’s Bridge at Argentueil and “Yellow Store Front” by Christo Which of these is art? Let the children voice their ideas. What if I told you that they are all art? Today we are going on a trip around the world to look at a pair of artists that do very creative work on a very large scale. They transform the ordinary into something that makes people stop and look at things in a different way. Slide 3 Show “Wrapped bottles and cans” and “wrapped object” Can anyone tell me what these objects are? Is this how you normally see them? What is your initial reaction to it? What could be in the package on the right? Does it make you think and wonder? Why would an artist want to express themselves by wrapping or covering something? What comment would they be making? When we look at art, some of the tools we use to talk about it are the Elements of Art: Color, light, line, shape, texture and space (composition). -

The Tom Golden Collection

The Tom Golden Collection 2001.51.1 “Running Fence‐‐Project for Sonoma and Marin Counties." Artist: Christo, 1974. Original drawing collage for Running Fence project. Signed: "CHRISTO, 1974", (lower left above title). L 28 x W 22. 2001.51.2 “Wrapped Walk Ways‐‐Project for Loose Park, Kansas City, Missouri." Artist: Christo, 1978. Original collages photograph by Wolfgang Volz. Signed: "CHRISTO, 1978" (Right 2001.51.3.1 “Surrounded Islands‐‐Project for Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida." Artist: Christo, 1983. Collage with fabric, pastel, charcoal, pencil, crayon, enamel paint, fabric sample, and aerial photograph. TWO PARTS (A‐B). Signed: "CHRISTO, 1983" (lower right 2001.51.3.2 “Surrounded Island Project for Biscayne Bay, Greater Miami, Florida." Artist: Christo, 1983. Collage with fabric, pastel, charcoal, pencil, crayon, enamel paint, fabric sample, and aerial photography. Two of two parts. Signed: "CHRISTO 1983" (lower right on sample fabric.) 2001.51.4 “The Pont Neuf, Wrapped‐‐Project for Paris." Artist: Christo, 1979. Collages photograph (pencil, enamel paint, crayon, charcoal, and photograph by Wolfgang Volz on paper). Signed: "CHRISTO, 1979" (Lower left). 2001.51.5 "For Tom Sept, 1985 Paris." Original instructional ink sketch is of a lamp post of Christo and Jeanne‐Claude, The Pont Neuf, Wrapped (Project for Paris). Artist: Christo, 1985. Signed across the bottom "For Tom Sept, 1985 Paris CHRISTO." 2001.51.6 "For Tom, With Love, Many Thanks." Artist: Christo, 1985. Original sketch was done to show how four barrel sculptures were to be reassembled in Basel, Switzerland and be photographed for documentation by Eeva‐Enkeri for Christo and Jeanne‐Claude. -

Christo and Jeanne-Claude

Christo and Jeanne-Claude Gabrovo, 1942 Christo (left) and his two brothers Stefan (center) and Anani (right) Photo: Vladimir Yavachev © 1942 Christo 1935 Christo: American, Bulgarian-born Christo Vladimirov Javacheff, June 13, 1935, Gabrovo, of a Bulgarian industrialist family. Jeanne-Claude: American, French-born Jeanne-Claude Marie Denat, June 13, 1935, Casablanca, of a French military family, educated in France and Switzerland. Died November 18, 2009, New York City. 1952 Jeanne-Claude: Baccalauréat in Latin and Philosophy, University of Tunis, Tunisia. 1953-56 Christo: Studies at the National Academy of Art, Sofia, Bulgaria. Gabrovo, 1949 Christo (left) during a drawing lesson Photo: Archive © 1949 Christo 1956 In fall, Christo leaves Bulgaria to go to Prague, Czechoslovakia. 1957 On January 10, Christo escapes to Vienna, Austria, where he studies one semester at the Academy of Fine Arts. In October, he moves to Geneva, Switzerland. 1958 In March, Christo arrives in Paris, where he meets Jeanne-Claude in early October. Packages and Wrapped Objects. 1960 Birth of their son, Cyril, May 11. 1961 Project for a Wrapped Public Building. Stacked Oil Barrels and Dockside Packages, Cologne Harbor, 1961. Rolls of paper, oil barrels, tarpaulin and rope. Duration: two weeks. Christo and Jeanne-Claude's first collaboration. Paris, 1961 Christo in his studio at 14 rue de Saint-Senoch Photo: Jean-Jacques Lévèque 1962 Wall of Oil Barrels – The Iron Curtain, Rue Visconti, Paris, 1961-62. 89 barrels. Height: 13.7 feet (4.2 meters). Width: 13.2 feet (4 meters). Depth: 2.7 feet (0.5 meters). Duration: eight hours. Stacked Oil Barrels, Gentilly, near Paris, France.