ER Paleoproteomics of Mesozoic Dinosaurs and Other Mesozoic Fossils

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

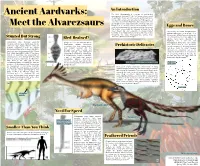

Smaller Than You Think Bird-Brained? Need for Speed

An Introduction The clade Alvarezsauria is a group of small-bodied Ancient Aardvarks: [10] maniraptoran dinosaurs. The first known alvarezsaurid, Alvarezsaurus calvoi, was discovered in partial remains in the late 20th century, and named by Jose F. Bonaparte. A. calvoi was uncovered in Argentina, but today alvarezsaurs are known to have ranged across the Americas, Asia, and Meet the Alvarezsaurs Europe.[10] It is currently estimated that members of this Eggs and Bones clade existed between the Late Jurassic and the Cretaceous. This feather covered bird-like dinosaur is known for its insect based diet and especially its unique hooked The recently discovered Bonapartenykus forelimbs. These highly derived and powerful arms evolved ultimus represents a new genus of of throughout the clade Alvarezsauridae, giving these Alvarezsaurs. A 70 million year old pocket [12] Stunted But Strong dinosaurs a predatory advantage. of fossilized bones and two eggs of this Bird-Brained? species have been discovered in Argentina. This is the first time Alvarezsaurs have strangely powerful Using a cast of a skull from the species Alvarezsaurus bones and egg remains forearms, with one large thumb claw and the Ceratonykus oculatus, researchers have been found in close proximity. other two digits highly reduced. They are reconstructed an alvarezsaurian brain. Prehistoric Delicacies Though evidence of brooding behavior radically transformed from the typical Their analysis revealed that this has been found for other theropod theropod forelimb, which is longer, with three dinosaur had acute hearing and dinosaurs, no conclusion can yet be [10] functional digits and grasping ability. Given excellent eyesight, with intelligence drawn for Alvareszsaurs as no indication their highly specialized nature, it has been comparable to living birds. -

Full Text (1005.6

Osteology of the Late Cretaceous alvarezsauroid Linhenykus monodactylus from China and comments on alvarezsauroid biogeography XING XU, PAUL UPCHURCH, QINGYU MA, MICHAEL PITTMAN, JONAH CHOINIERE, CORWIN SULLIVAN, DAVID W.E. HONE, QINGWEI TAN, LIN TAN, DONG XIAO, and FENGLU HAN Xu, X., Upchurch, P., Ma, Q., Pittman, M., Choiniere, J., Sullivan, C., Hone, D.W.E., Tan, Q., Tan, L., Xiao, D., and Han, F. 2013. Osteology of the Late Cretaceous alvarezsauroid Linhenykus monodactylus from China and comments on alvarez− sauroid biogeography. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 58 (1): 25–46. The alvarezsauroid theropod Linhenykus monodactylus from the Upper Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia, China is the first known monodactyl non−avian dinosaur, providing important information on the complex patterns of manual evolution seen in alvarezsauroids. Here we provide a detailed description of the osteology of this taxon. Linhenykus shows a number of fea− tures that are transitional between parvicursorine and non−parvicursorine alvarezsauroids, but detailed comparisons also re− veal that some characters had a more complex distribution. We also use event−based tree−fitting to perform a quantitative analysis of alvarezsauroid biogeography incorporating several recently discovered taxa. The results suggest that there is no statistical support for previous biogeographic hypotheses that favour pure vicariance or pure dispersal scenarios as explana− tions for the distributions of alvarezsauroids across South America, North America and Asia. Instead, statistically significant biogeographic reconstructions suggest a dominant role for sympatric (or “within area”) events, combined with a mix of vicariance, dispersal and regional extinction. At present the alvarezsauroid data set is too small to completely resolve the biogeographic history of this group: future studies will need to create larger data sets that encompass additional clades. -

Written in Stone

112 W RITTENIN S TONE had yet been undertaken (the fossil had only come to the attention of Canadian paleontologist Phil Currie and paleo-artist Michael Skrepnick two weeks earlier), the specimen confirmed the connection between dino- saurs and birds that had been proposed on bones alone. The new dino- saur was dubbed Sinosauropteryx, and it had come from Cretaceous deposits in China that exhibited a quality of preservation that exceeded that of the Solnhofen limestone. Sinosauropteryx was only the first feathered dinosaur to be an- nounced. A panoply of feathered fossils started to turn up in the Jurassic and Cretaceous strata of China, each just as magnificent as the one be- fore. There were early birds that still retained clawed hands (Confuciu- sornis) and teeth (Sapeornis, Jibeinia), while non-flying coelurosaurs such as Caudipteryx, Sinornithosaurus, Jinfengopteryx, Dilong, and Beipiaosaurus wore an array of body coverings from wispy fuzz to full flight feathers. The fossil feathers of the strange, stubby-armed dinosaur Shuvuuia even preserved the biochemical signature of beta-keratin, a protein present in the feathers of living birds, and quill knobs on the forearm of Velociraptor reported in 2007 confirmed that the famous predator was covered in feathers, too. As new discoveries continued to accumulate it became apparent that almost every group of coelurosaurs had feathered representatives, from the weird secondarily herbivorous forms such as Beipiaosaurus to Dilong, an early relative of Tyrannosaurus. It is even possible that, FIGURE 37 - A Velociraptor attempts to catch the early bird Confuciusornis. Both were feathered dinosaurs. 113 Footprints and Feathers during its early life, the most famous of the flesh-tearing dinosaurs may have been covered in a coat of dino-fuzz. -

American Museum Novitates

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Number 3899, 44 pp. April 26, 2018 A Second Specimen of Citipati osmolskae Associated with a Nest of Eggs from Ukhaa Tolgod, Omnogov Aimag, Mongolia MARK A. NORELL,1, 2 AMY M. BALANOFF,1, 3 DANIEL E. BARTA,1, 2 AND GREGORY M. ERICKSON1, 4 ABSTRACT Adult dinosaurs preserved attending their nests in brooding positions are among the rarest vertebrate fossils. By far the most common occurrences are members of the dinosaur group Oviraptorosauria. The first finds of these were specimens recovered from the Djadokhta Forma- tion at the Mongolian locality of Ukhaa Tolgod and the Chinese locality of Bayan Mandahu. Since the initial discovery of these specimens, a few more occurrences of nesting oviraptors have been found at other Asian localities. Here we report on a second nesting oviraptorid specimen (IGM 100/1004) sitting in a brooding position atop a nest of eggs from Ukhaa Tolgod, Omnogov, Mongolia. This is a large specimen of the ubiquitous Ukhaa Tolgod taxon Citipati osmolskae. It is approximately 11% larger based on humeral length than the original Ukhaa Tolgod nesting Citipati osmolskae specimen (IGM 100/979), yet eggshell structure and egg arrangement are identical. No evidence for colonial breeding of these animals has been recovered. Reexamination of another “nesting” oviraptorosaur, the holotype of Oviraptor philoceratops (AMNH FARB 6517) indicates that in addition to the numerous partial eggs associated with the original skeleton that originally led to its referral as a protoceratopsian predator, there are the remains of a tiny theropod. This hind limb can be provisionally assigned to Oviraptoridae. It is thus at least possible that some of the eggs associated with the holotype had hatched and the perinates had not left the nest. -

Skeletal Completeness of the Non‐Avian Theropod Dinosaur Fossil

University of Birmingham Skeletal completeness of the non-avian theropod dinosaur fossil record Cashmore, Daniel; Butler, Richard DOI: 10.1111/pala.12436 License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Cashmore, D & Butler, R 2019, 'Skeletal completeness of the non-avian theropod dinosaur fossil record', Palaeontology, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 951-981. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12436 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Cashmore, D & Butler, R (2019), 'Skeletal completeness of the non-avian theropod dinosaur fossil record', Palaeontology, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 951-981. © 2019 The Authors 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12436 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

Avialan Status for Oviraptorosauria

Avialan status for Oviraptorosauria TERESA MARYAŃSKA, HALSZKA OSMÓLSKA, and MIECZYSŁAW WOLSAN Maryańska, T., Osmólska, H., and Wolsan, M. 2002. Avialan status for Oviraptorosauria. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 47 (1): 97–116. Oviraptorosauria is a clade of Cretaceous theropod dinosaurs of uncertain affinities within Maniraptoriformes. All pre− vious phylogenetic analyses placed oviraptorosaurs outside a close relationship to birds (Avialae), recognizing Dromaeo− sauridae or Troodontidae, or a clade containing these two taxa (Deinonychosauria), as sister taxon to birds. Here we pres− ent the results of a phylogenetic analysis using 195 characters scored for four outgroup and 13 maniraptoriform (ingroup) terminal taxa, including new data on oviraptorids. This analysis places Oviraptorosauria within Avialae, in a sister−group relationship with Confuciusornis. Archaeopteryx, Therizinosauria, Dromaeosauridae, and Ornithomimosauria are suc− cessively more distant outgroups to the Confuciusornis−oviraptorosaur clade. Avimimus and Caudipteryx are succes− sively more closely related to Oviraptoroidea, which contains the sister taxa Caenagnathidae and Oviraptoridae. Within Oviraptoridae, “Oviraptor” mongoliensis and Oviraptor philoceratops are successively more closely related to the Conchoraptor−Ingenia clade. Oviraptorosaurs are hypothesized to be secondarily flightless. Emended phylogenetic defi− nitions are provided for Oviraptoridae, Caenagnathidae, Oviraptoroidea, Oviraptorosauria, Avialae, Eumaniraptora, Maniraptora, and Maniraptoriformes. -

Haplocheirus Sollers Choiniere Et Al., 2010 (Theropoda: Alvarezsauroidea)

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Number 3816, 44 pp. October 22, 2014 Cranial osteology of Haplocheirus sollers Choiniere et al., 2010 (Theropoda: Alvarezsauroidea) JONAH N. CHOINIERE,1,2,3 JAMES M. CLARK,2 MARK A. NORELL,3 AND XING XU4 ABSTRacT The basalmost alvarezsauroid Haplocheirus sollers is known from a single specimen col- lected in Upper Jurassic (Oxfordian) beds of the Shishugou Formation in northwestern China. Haplocheirus provides important data about the plesiomorphic morphology of the theropod group Alvarezsauroidea, whose derived members possess numerous skeletal autapomorphies. We present here a detailed description of the cranial anatomy of Haplocheirus. These data are important for understanding cranial evolution in Alvarezsauroidea because other basal mem- bers of the clade lack cranial material entirely and because derived parvicursorine alvarezsau- roids have cranial features shared exclusively with members of Avialae that have been interpreted as synapomorphies in some analyses. We discuss the implications of this anatomy for cranial evolution within Alvarezsauroidea and at the base of Maniraptora. INTRODUCTION Alvarezsauroidea is a clade of theropod dinosaurs whose derived members possess remarkably birdlike features, including a lightly built, kinetic skull, several vertebral modi- fications, a keeled sternum, a fused carpometacarpus, a fully retroverted pubis and ischium 1 Evolutionary Studies Institute, University of the Witwatersrand; DST/NRF Centre of Excellence in Palaeo- sciences, University of the Witwatersrand. 2 Department of Biological Sciences, George Washington University. 3 Division of Paleontology, American Museum of Natural History. 4 Key Laboratory of Vertebrate Evolution and Human Origins, Institute for Vertebrate Paleontology and Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences. Copyright © American Museum of Natural History 2014 ISSN 0003-0082 2 AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES NO. -

Herbivorous Ecomorphology and Specialization Patterns in Theropod Dinosaur Evolution

Herbivorous ecomorphology and specialization patterns in theropod dinosaur evolution Lindsay E. Zanno1 and Peter J. Makovicky Department of Geology, The Field Museum, Chicago, IL 60605 Edited by Randall Irmis, Department of Geology and Geophysics, University of Utah, Salt Lake City, UT, and accepted by the Editorial Board November 10, 2010 (received for review August 16, 2010) Interpreting key ecological parameters, such as diet, of extinct characteristics have been used to propose a myriad of dietary organisms without the benefit of direct observation or explicit preferences with little consensus (8, 11, 15–20). fossil evidence poses a formidable challenge for paleobiological Recently, a burst of theropod dinosaur discoveries bearing an studies. To date, dietary categorizations of extinct taxa are largely unexpected degree of ecomorphological disparity (particularly generated by means of modern analogs; however, for many with respect to dental anatomy) (12, 20–24) has sparked species the method is subject to considerable ambiguity. Here a renewed interest in the diet of coelurosaurian species. Yet, to we present a refined approach for assessing trophic habits in fossil date, a large scale quantitative analysis on theropod ecomor- taxa and apply the method to coelurosaurian dinosaurs—a clade phology has not been conducted. Serendipitously, an increasing for which diet is particularly controversial. Our findings detect 21 number of theropod specimens preserve unequivocal evidence of morphological features that exhibit statistically significant corre- diet in the form of fossilized gut contents (25–27), coprolites lations with extrinsic fossil evidence of coelurosaurian herbivory, (28), or a gastric mill (21–23, 29–31), which are known to cor- such as stomach contents and a gastric mill. -

Reanalysis of Putative Ovarian Follicles Suggests That Early Cretaceous Birds Were Feeding Not Breeding Gerald Mayr1*, Thomas G

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Reanalysis of putative ovarian follicles suggests that Early Cretaceous birds were feeding not breeding Gerald Mayr1*, Thomas G. Kaye2, Michael Pittman3, Evan T. Saitta4 & Christian Pott5 We address the identity of putative ovarian follicles in Early Cretaceous bird fossils from the Jehol Biota (China), whose identifcation has previously been challenged. For the frst time, we present a link to the botanical fossil record, showing that the “follicles” of some enantiornithine fossils resemble plant propagules from the Jehol Biota, which belong to Carpolithes multiseminalis. The botanical afnities of this “form-taxon” are currently unresolved, but we note that C. multiseminalis propagules resemble propagules associated with cone-like organs described as Strobilites taxusoides, which in turn are possibly associated with sterile foliage allocated to Liaoningcladus. Laser-Stimulated Fluorescence imaging furthermore reveals diferent intensities of fuorescence of “follicles” associated with a skeleton of the confuciusornithid Eoconfuciusornis zhengi, with a non-fuorescent circular micro-pattern indicating carbonaceous (or originally carbonaceous) matter. This is inconsistent with the interpretation of these structures as ovarian follicles. We therefore reafrm that the “follicles” represent ingested food items, and even though the exact nature of the Eoconfuciusornis stomach contents remains elusive, at least some enantiornithines ingested plant propagules. Over the past decades, the Jehol Biota in northeast China yielded an extraordinary diversity of fossils, which produced unprecedented insights into Early Cretaceous ecosystems. Even though the specimens from these localities are known for their exquisite sof-tissue preservation, the discovery of putative ovarian follicles in some of the bird fossils stands out and is otherwise unmatched in the avian fossil record. -

Supporting Information Appendix to the First Known Monodactyl Non

Supporting Information Appendix to The first known monodactyl non-avian dinosaur and the complex evolution of the alvarezsauroid hand Xing Xu1*, Corwin Sullivan1, Michael Pittman2, Jonah Choiniere3, David W. E. Hone1, Paul Upchurch2, Qingwei Tan4, Dong Xiao5, Lin Tan4, and Fenglu Han1 1Key Laboratory of Evolutionary Systematics of Vertebrates, Institute of Vertebrate Paleontology & Paleoanthropology, Chinese Academy of Sciences, 142 Xiwai Street, Beijing 100044 2Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, Gower Street, London, WC1E 6BT, U.K. 3Department of Biological Sciences, George Washington University, 2023 G Street NW, Washington, DC 20052 4Long Hao Institute of Geology and Paleontology, Hohhot, Nei Mongol 010010, China 5Department of Land and Resources, Linhe, Nei Mongol 015000, China 1. Selected measurements of Linhenykus monodactylus holotype 2. Length comparisons of selected elements in Mononykus, Parvicursor, Shuvuuia, and Linhenykus 3. Cladistic analysis 4. Biogeography of the Alvarezsauroidea 5. References 1. Selected measurements of Linhenykus monodactylus holotype (in mm; *estimated value) Middle cervical centrum length 9.0 Middle dorsal centrum length 8.2 Posterior dorsal centrum length 7.6 Middle sacral centrum length 7.3 Caudal 1 centrum length 7.3 Caudal 2 centrum length 8.3 Caudal 3 centrum length 8.7 Caudal 4 centrum length 8.7 Caudal 5 centrum length 7.7 Caudal 6 centrum length 7.6 Caudal 7 centrum length 7.6 Caudal 8 centrum length 7.1 Caudal 9 centrum length 6.4 Sternum length 7.7 Sternum width 7.2 Metacarpal II length 7.1 Metacarpal II width 7.7 Metacarpal III length 5.1 Manual phalanx II-1 length 11.9 Manual phalanx II-1 width 6.0 Manual phalanx II-2 length 15.9 Femur length 70* Tibia length 97.5 Metatarsal II length 68.0 Metatarsal III length 31.0 Metatarsal IV length 68.5* Pedal phalanx II-1 length 11.3 Pedal phalanx III-2 length 6.9 Pedal phalanx IV-1 length 7.6 Pedal phalanx IV-3 length 4.0 Pedal phalanx IV-4 length 3.8* Pedal phalanx IV-5 length 8.0 2. -

Unenlagiid Theropods: Are They Members of the Dromaeosauridae (Theropoda, Maniraptora)?

“main” — 2011/2/10 — 14:01 — page 117 — #1 Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2011) 83(1): 117-162 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 www.scielo.br/aabc Unenlagiid theropods: are they members of the Dromaeosauridae (Theropoda, Maniraptora)? , FEDERICO L. AGNOLIN1 2 and FERNANDO E. NOVAS1 1Laboratorio de Anatomía Comparada y Evolución de los Vertebrados Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales “Bernardino Rivadavia” Ángel Gallardo, 470 (1405BDB), Buenos Aires, Argentina 2Fundación de Historia Natural “Félix de Azara”, Departamento de Ciencias Naturales y Antropología CEBBAD, Universidad Maimónides, Valentín Virasoro 732 (1405BDB), Buenos Aires, Argentina Manuscript received on November 9, 2009; accepted for publication on June 21, 2010 ABSTRACT In the present paper we analyze the phylogenetic position of the derived Gondwanan theropod clade Unen- lagiidae. Although this group has been frequently considered as deeply nested within Deinonychosauria and Dromaeosauridae, most of the features supporting this interpretation are conflictive, at least. Modification of integrative databases, such as that recently published by Hu et al. (2009), produces significant changes in the topological distribution of taxa within Deinonychosauria, depicting unenlagiids outside this clade. Our analysis retrieves, in contrast, a monophyletic Avialae formed by Unenlagiidae plus Aves. Key words: Gondwana, Deinonychosauria, Dromaeosauridae, Unenlagiidae, Avialae. INTRODUCTION Until recently, the deinonychosaurian fossil record has been geographically restricted to the Northern Hemisphere (Norell and Makovicky 2004), but recent discoveries demonstrated that they were also present and highly diversified in the Southern landmasses, suggesting that an important adaptive radiation took place in Gondwana during the Cretaceous. Gondwanan dromaeosaurids have been documented from Turonian through Maastrichtian beds of Argentina (Makovicky et al. -

Modeling the Evolution of Substrate Use in the Hands And

MODELING THE EVOLUTION OF SUBSTRATE USE IN THE HANDS AND FEET OF PRIMATES, BIRDS, AND NON-AVIAN THEROPOD DINOSAURS by Josef Barrett Stiegler A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Earth Sciences MONTANA STATE UNIVERSITY Bozeman, Montana May, 2012 ©COPYRIGHT by Josef Barrett Stiegler 2012 All Rights Reserved ii APPROVAL of a thesis submitted by Josef Barrett Stiegler This thesis has been read by each member of the thesis committee and has been found to be satisfactory regarding content, English usage, format, citation, bibliographic style, and consistency, and is ready for submission to The Graduate School. Dr. David J. Varricchio Approved for the Department of Earth Sciences Dr. David Mogk Approved for The Graduate School Dr. Carl A. Fox iii STATEMENT OF PERMISSION TO USE In presenting this thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for a master’s degree at Montana State University, I agree that the Library shall make it available to borrowers under rules of the Library. If I have indicated my intention to copyright this thesis by including a copyright notice page, copying is allowable only for scholarly purposes, consistent with “fair use” as prescribed in the U.S. Copyright Law. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this thesis in whole or in parts may be granted only by the copyright holder. Josef Barrett Stiegler May 2012 iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First I would like to thank my committee members David Varricchio, Jack Horner, and David Willey for their support throughout my time at Montana State and guidance on this project.