Supporting Information Appendix to the First Known Monodactyl Non

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

From the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia

AMEGHINIANA (Rev. Asoc. Paleontol. Argent.) - 40 (1): 119-122. Buenos Aires, 30-03-2003 ISSN0002-7014 NOTA PALEONTOLÓGICA A new specimen of Patagonykus puertai (Theropoda: Alvarezsauridae) from the Late Cretaceous of Patagonia Luis M. CHIAPPE1and Rodolfo A. CORIA2 Introduction Systematic paleontology With their short and robust forelimbs, highly ki- THEROPODA netic skulls, and a host of unique skeletal features, COELUROSAURIA alvarezsaurids are highly specialized Mesozoic ALVAREZSAURIDAEBonaparte, 1991 coelurosaurian theropods known from the Late Cretaceous of Asia, North, and South America Genus PatagonykusNovas, 1997a (Chiappe et al., 2002). Despite abundant and well- preserved material from the Gobi Desert of Patagonykussp. cf. P. puertaiNovas, 1997a Mongolia, the phylogenetic relationships of al- Figures 1 and 2 varezsaurids have remained unclear (Chiappe et Material. MCF-PVPH-102 (Museo Carmen Funes, al., 2002; Novas and Pol, 2002; Suzuki et al., 2002). Paleontología de Vertebrados; Plaza Huincul, The most basal alvarezsaurids are from South Neuquén, Argentina), an articulated phalanx 1 and 2 America and are limited to just two taxa from the (ungual) of the left manual digit I. Patagonian province of Neuquén (Argentina), Geographical provenance and geological horizon. Alvarezsaurus calvoi (Bonaparte, 1991) and Northern shore of Los Barriales lake, approximately Patagokykus puertai (Novas, 1997a), which although 80 km north Plaza Huincul. Because the specimen poorly represented are important because they was not collected by professionals, no precise strati- have been consistently interpreted as the most ple- graphic information is available; nonetheless, only siomorphic members of the group (Novas, 1996; the Late Cretaceous Neuquén Group outcrops in this Chiappe et al., 1998). area. Also, considering that the holotype specimen of Here we report on a second specimen of Patagonykus puertaiwas found in beds attributed to Patagonykus, which we assign to the species P. -

Onetouch 4.0 Scanned Documents

/ Chapter 2 THE FOSSIL RECORD OF BIRDS Storrs L. Olson Department of Vertebrate Zoology National Museum of Natural History Smithsonian Institution Washington, DC. I. Introduction 80 II. Archaeopteryx 85 III. Early Cretaceous Birds 87 IV. Hesperornithiformes 89 V. Ichthyornithiformes 91 VI. Other Mesozojc Birds 92 VII. Paleognathous Birds 96 A. The Problem of the Origins of Paleognathous Birds 96 B. The Fossil Record of Paleognathous Birds 104 VIII. The "Basal" Land Bird Assemblage 107 A. Opisthocomidae 109 B. Musophagidae 109 C. Cuculidae HO D. Falconidae HI E. Sagittariidae 112 F. Accipitridae 112 G. Pandionidae 114 H. Galliformes 114 1. Family Incertae Sedis Turnicidae 119 J. Columbiformes 119 K. Psittaciforines 120 L. Family Incertae Sedis Zygodactylidae 121 IX. The "Higher" Land Bird Assemblage 122 A. Coliiformes 124 B. Coraciiformes (Including Trogonidae and Galbulae) 124 C. Strigiformes 129 D. Caprimulgiformes 132 E. Apodiformes 134 F. Family Incertae Sedis Trochilidae 135 G. Order Incertae Sedis Bucerotiformes (Including Upupae) 136 H. Piciformes 138 I. Passeriformes 139 X. The Water Bird Assemblage 141 A. Gruiformes 142 B. Family Incertae Sedis Ardeidae 165 79 Avian Biology, Vol. Vlll ISBN 0-12-249408-3 80 STORES L. OLSON C. Family Incertae Sedis Podicipedidae 168 D. Charadriiformes 169 E. Anseriformes 186 F. Ciconiiformes 188 G. Pelecaniformes 192 H. Procellariiformes 208 I. Gaviiformes 212 J. Sphenisciformes 217 XI. Conclusion 217 References 218 I. Introduction Avian paleontology has long been a poor stepsister to its mammalian counterpart, a fact that may be attributed in some measure to an insufRcien- cy of qualified workers and to the absence in birds of heterodont teeth, on which the greater proportion of the fossil record of mammals is founded. -

Re-Evaluation of the Haarlem Archaeopteryx and the Radiation of Maniraptoran Theropod Dinosaurs Christian Foth1,3 and Oliver W

Foth and Rauhut BMC Evolutionary Biology (2017) 17:236 DOI 10.1186/s12862-017-1076-y RESEARCH ARTICLE Open Access Re-evaluation of the Haarlem Archaeopteryx and the radiation of maniraptoran theropod dinosaurs Christian Foth1,3 and Oliver W. M. Rauhut2* Abstract Background: Archaeopteryx is an iconic fossil that has long been pivotal for our understanding of the origin of birds. Remains of this important taxon have only been found in the Late Jurassic lithographic limestones of Bavaria, Germany. Twelve skeletal specimens are reported so far. Archaeopteryx was long the only pre-Cretaceous paravian theropod known, but recent discoveries from the Tiaojishan Formation, China, yielded a remarkable diversity of this clade, including the possibly oldest and most basal known clade of avialan, here named Anchiornithidae. However, Archaeopteryx remains the only Jurassic paravian theropod based on diagnostic material reported outside China. Results: Re-examination of the incomplete Haarlem Archaeopteryx specimen did not find any diagnostic features of this genus. In contrast, the specimen markedly differs in proportions from other Archaeopteryx specimens and shares two distinct characters with anchiornithids. Phylogenetic analysis confirms it as the first anchiornithid recorded outside the Tiaojushan Formation of China, for which the new generic name Ostromia is proposed here. Conclusions: In combination with a biogeographic analysis of coelurosaurian theropods and palaeogeographic and stratigraphic data, our results indicate an explosive radiation of maniraptoran coelurosaurs probably in isolation in eastern Asia in the late Middle Jurassic and a rapid, at least Laurasian dispersal of the different subclades in the Late Jurassic. Small body size and, possibly, a multiple origin of flight capabilities enhanced dispersal capabilities of paravian theropods and might thus have been crucial for their evolutionary success. -

Smaller Than You Think Bird-Brained? Need for Speed

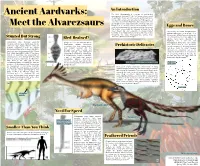

An Introduction The clade Alvarezsauria is a group of small-bodied Ancient Aardvarks: [10] maniraptoran dinosaurs. The first known alvarezsaurid, Alvarezsaurus calvoi, was discovered in partial remains in the late 20th century, and named by Jose F. Bonaparte. A. calvoi was uncovered in Argentina, but today alvarezsaurs are known to have ranged across the Americas, Asia, and Meet the Alvarezsaurs Europe.[10] It is currently estimated that members of this Eggs and Bones clade existed between the Late Jurassic and the Cretaceous. This feather covered bird-like dinosaur is known for its insect based diet and especially its unique hooked The recently discovered Bonapartenykus forelimbs. These highly derived and powerful arms evolved ultimus represents a new genus of of throughout the clade Alvarezsauridae, giving these Alvarezsaurs. A 70 million year old pocket [12] Stunted But Strong dinosaurs a predatory advantage. of fossilized bones and two eggs of this Bird-Brained? species have been discovered in Argentina. This is the first time Alvarezsaurs have strangely powerful Using a cast of a skull from the species Alvarezsaurus bones and egg remains forearms, with one large thumb claw and the Ceratonykus oculatus, researchers have been found in close proximity. other two digits highly reduced. They are reconstructed an alvarezsaurian brain. Prehistoric Delicacies Though evidence of brooding behavior radically transformed from the typical Their analysis revealed that this has been found for other theropod theropod forelimb, which is longer, with three dinosaur had acute hearing and dinosaurs, no conclusion can yet be [10] functional digits and grasping ability. Given excellent eyesight, with intelligence drawn for Alvareszsaurs as no indication their highly specialized nature, it has been comparable to living birds. -

Full Text (1005.6

Osteology of the Late Cretaceous alvarezsauroid Linhenykus monodactylus from China and comments on alvarezsauroid biogeography XING XU, PAUL UPCHURCH, QINGYU MA, MICHAEL PITTMAN, JONAH CHOINIERE, CORWIN SULLIVAN, DAVID W.E. HONE, QINGWEI TAN, LIN TAN, DONG XIAO, and FENGLU HAN Xu, X., Upchurch, P., Ma, Q., Pittman, M., Choiniere, J., Sullivan, C., Hone, D.W.E., Tan, Q., Tan, L., Xiao, D., and Han, F. 2013. Osteology of the Late Cretaceous alvarezsauroid Linhenykus monodactylus from China and comments on alvarez− sauroid biogeography. Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 58 (1): 25–46. The alvarezsauroid theropod Linhenykus monodactylus from the Upper Cretaceous of Inner Mongolia, China is the first known monodactyl non−avian dinosaur, providing important information on the complex patterns of manual evolution seen in alvarezsauroids. Here we provide a detailed description of the osteology of this taxon. Linhenykus shows a number of fea− tures that are transitional between parvicursorine and non−parvicursorine alvarezsauroids, but detailed comparisons also re− veal that some characters had a more complex distribution. We also use event−based tree−fitting to perform a quantitative analysis of alvarezsauroid biogeography incorporating several recently discovered taxa. The results suggest that there is no statistical support for previous biogeographic hypotheses that favour pure vicariance or pure dispersal scenarios as explana− tions for the distributions of alvarezsauroids across South America, North America and Asia. Instead, statistically significant biogeographic reconstructions suggest a dominant role for sympatric (or “within area”) events, combined with a mix of vicariance, dispersal and regional extinction. At present the alvarezsauroid data set is too small to completely resolve the biogeographic history of this group: future studies will need to create larger data sets that encompass additional clades. -

A Fast-Growing Basal Troodontid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from The

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN A fast‑growing basal troodontid (Dinosauria: Theropoda) from the latest Cretaceous of Europe Albert G. Sellés1,2*, Bernat Vila1,2, Stephen L. Brusatte3, Philip J. Currie4 & Àngel Galobart1,2 A characteristic fauna of dinosaurs and other vertebrates inhabited the end‑Cretaceous European archipelago, some of which were dwarves or had other unusual features likely related to their insular habitats. Little is known, however, about the contemporary theropod dinosaurs, as they are represented mostly by teeth or other fragmentary fossils. A new isolated theropod metatarsal II, from the latest Maastrichtian of Spain (within 200,000 years of the mass extinction) may represent a jinfengopterygine troodontid, the frst reported from Europe. Comparisons with other theropods and phylogenetic analyses reveal an autapomorphic foramen that distinguishes it from all other troodontids, supporting its identifcation as a new genus and species, Tamarro insperatus. Bone histology shows that it was an actively growing subadult when it died but may have had a growth pattern in which it grew rapidly in early ontogeny and attained a subadult size quickly. We hypothesize that it could have migrated from Asia to reach the Ibero‑Armorican island no later than Cenomanian or during the Maastrichtian dispersal events. During the latest Cretaceous (ca. 77–66 million years ago) in the run-up to the end-Cretaceous mass extinc- tion, Europe was a series of islands populated by diverse and distinctive communities of dinosaurs and other vertebrates. Many of these animals exhibited peculiar features that may have been generated by lack of space and resources in their insular habitats. -

Written in Stone

112 W RITTENIN S TONE had yet been undertaken (the fossil had only come to the attention of Canadian paleontologist Phil Currie and paleo-artist Michael Skrepnick two weeks earlier), the specimen confirmed the connection between dino- saurs and birds that had been proposed on bones alone. The new dino- saur was dubbed Sinosauropteryx, and it had come from Cretaceous deposits in China that exhibited a quality of preservation that exceeded that of the Solnhofen limestone. Sinosauropteryx was only the first feathered dinosaur to be an- nounced. A panoply of feathered fossils started to turn up in the Jurassic and Cretaceous strata of China, each just as magnificent as the one be- fore. There were early birds that still retained clawed hands (Confuciu- sornis) and teeth (Sapeornis, Jibeinia), while non-flying coelurosaurs such as Caudipteryx, Sinornithosaurus, Jinfengopteryx, Dilong, and Beipiaosaurus wore an array of body coverings from wispy fuzz to full flight feathers. The fossil feathers of the strange, stubby-armed dinosaur Shuvuuia even preserved the biochemical signature of beta-keratin, a protein present in the feathers of living birds, and quill knobs on the forearm of Velociraptor reported in 2007 confirmed that the famous predator was covered in feathers, too. As new discoveries continued to accumulate it became apparent that almost every group of coelurosaurs had feathered representatives, from the weird secondarily herbivorous forms such as Beipiaosaurus to Dilong, an early relative of Tyrannosaurus. It is even possible that, FIGURE 37 - A Velociraptor attempts to catch the early bird Confuciusornis. Both were feathered dinosaurs. 113 Footprints and Feathers during its early life, the most famous of the flesh-tearing dinosaurs may have been covered in a coat of dino-fuzz. -

Some Maastrichtian Vertebrates from Fluvial Channel Fill Deposits at Pui (Hațeg Basin)

Muzeul Olteniei Craiova. Oltenia. Studii şi comunicări. Ştiinţele Naturii. Tom. 31, No. 2/2015 ISSN 1454-6914 SOME MAASTRICHTIAN VERTEBRATES FROM FLUVIAL CHANNEL FILL DEPOSITS AT PUI (HAȚEG BASIN) SOLOMON Alexandru, CODREA Vlad Abstract. Latest Cretaceous deposits are cropping out in various localities of the Hațeg basin (Romania). Among these localities Pui is of peculiar interest, being the southeastern most one where Maastrichtian fluvial deposits are exposed. These terrestrial deposits are represented mainly by red beds, which yielded since the end of the 19th century, rich vertebrate assemblages. From a channel fill block discovered ex situ, a diverse fossil vertebrate assemblage was recovered (turtles, crocodilians, pterosaurs, and various herbivore and carnivore dinosaurs). This study is focused on the fossil taxa collected from this block and their fossilization processes. Keywords: latest Cretaceous, fluvial deposits, vertebrates, Hațeg basin, Romania. Rezumat. Câteva vertebrate maastrichtiene din depozite de canal fluvial de la Pui (Bazinul Hațeg). Depozite cretacic terminale aflorează în varii localități din Bazinul Hațeg (România). Dintre acestea, Pui este localizată în extremitatea sud-estică a bazinului, unde apar la zi depozite fluviale maastrichtiene. Aceste depozite sunt dominate de red beds, din care au fost colectate, încă de la finele secolului XIX, bogate asociații de vertebrate fosile. Dintr-un bloc cu umplutură de canal descoperit ex situ a fost extrasă o asociație diversă de vertebrate fosile (țestoase, crocodili, pterosauri și variați dinozauri erbivori și carnivori). Asociația de fosile din acest bloc și procesele de fosilizare evidențiate sunt descrise în acest studiu. Cuvinte cheie: Cretacic terminal, depozite fluviale, vertebrate, Bazinul Hațeg, România. INTRODUCTION In latest Cretaceous, an emerged land occurred in the actual Transylvania named the “Hațeg Island”. -

American Museum Novitates

AMERICAN MUSEUM NOVITATES Number 3899, 44 pp. April 26, 2018 A Second Specimen of Citipati osmolskae Associated with a Nest of Eggs from Ukhaa Tolgod, Omnogov Aimag, Mongolia MARK A. NORELL,1, 2 AMY M. BALANOFF,1, 3 DANIEL E. BARTA,1, 2 AND GREGORY M. ERICKSON1, 4 ABSTRACT Adult dinosaurs preserved attending their nests in brooding positions are among the rarest vertebrate fossils. By far the most common occurrences are members of the dinosaur group Oviraptorosauria. The first finds of these were specimens recovered from the Djadokhta Forma- tion at the Mongolian locality of Ukhaa Tolgod and the Chinese locality of Bayan Mandahu. Since the initial discovery of these specimens, a few more occurrences of nesting oviraptors have been found at other Asian localities. Here we report on a second nesting oviraptorid specimen (IGM 100/1004) sitting in a brooding position atop a nest of eggs from Ukhaa Tolgod, Omnogov, Mongolia. This is a large specimen of the ubiquitous Ukhaa Tolgod taxon Citipati osmolskae. It is approximately 11% larger based on humeral length than the original Ukhaa Tolgod nesting Citipati osmolskae specimen (IGM 100/979), yet eggshell structure and egg arrangement are identical. No evidence for colonial breeding of these animals has been recovered. Reexamination of another “nesting” oviraptorosaur, the holotype of Oviraptor philoceratops (AMNH FARB 6517) indicates that in addition to the numerous partial eggs associated with the original skeleton that originally led to its referral as a protoceratopsian predator, there are the remains of a tiny theropod. This hind limb can be provisionally assigned to Oviraptoridae. It is thus at least possible that some of the eggs associated with the holotype had hatched and the perinates had not left the nest. -

Skeletal Completeness of the Non‐Avian Theropod Dinosaur Fossil

University of Birmingham Skeletal completeness of the non-avian theropod dinosaur fossil record Cashmore, Daniel; Butler, Richard DOI: 10.1111/pala.12436 License: Creative Commons: Attribution (CC BY) Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Citation for published version (Harvard): Cashmore, D & Butler, R 2019, 'Skeletal completeness of the non-avian theropod dinosaur fossil record', Palaeontology, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 951-981. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12436 Link to publication on Research at Birmingham portal Publisher Rights Statement: Cashmore, D & Butler, R (2019), 'Skeletal completeness of the non-avian theropod dinosaur fossil record', Palaeontology, vol. 62, no. 6, pp. 951-981. © 2019 The Authors 2019. https://doi.org/10.1111/pala.12436 General rights Unless a licence is specified above, all rights (including copyright and moral rights) in this document are retained by the authors and/or the copyright holders. The express permission of the copyright holder must be obtained for any use of this material other than for purposes permitted by law. •Users may freely distribute the URL that is used to identify this publication. •Users may download and/or print one copy of the publication from the University of Birmingham research portal for the purpose of private study or non-commercial research. •User may use extracts from the document in line with the concept of ‘fair dealing’ under the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988 (?) •Users may not further distribute the material nor use it for the purposes of commercial gain. Where a licence is displayed above, please note the terms and conditions of the licence govern your use of this document. -

Redalyc.Unenlagiinae Revisited: Dromaeosaurid Theropods From

Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências ISSN: 0001-3765 [email protected] Academia Brasileira de Ciências Brasil GIANECHINI, FEDERICO A.; APESTEGUÍA, SEBASTIÁN Unenlagiinae revisited: dromaeosaurid theropods from South America Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências, vol. 83, núm. 1, marzo, 2011, pp. 163-195 Academia Brasileira de Ciências Rio de Janeiro, Brasil Available in: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=32717681008 How to cite Complete issue Scientific Information System More information about this article Network of Scientific Journals from Latin America, the Caribbean, Spain and Portugal Journal's homepage in redalyc.org Non-profit academic project, developed under the open access initiative “main” — 2011/2/10 — 14:11 — page 163 — #1 Anais da Academia Brasileira de Ciências (2011) 83(1): 163-195 (Annals of the Brazilian Academy of Sciences) Printed version ISSN 0001-3765 / Online version ISSN 1678-2690 www.scielo.br/aabc Unenlagiinae revisited: dromaeosaurid theropods from South America FEDERICO A. GIANECHINI and SEBASTIÁN APESTEGUÍA CONICET – Área de Paleontología, Fundación de Historia Natural ‘Félix de Azara’ Departamento de Ciencias Naturales y Antropología CEBBAD, Universidad Maimónides, Hidalgo 775 (1405BDB), Ciudad Autónoma de Buenos Aires, Argentina Manuscript received on October 30, 2009; accepted for publication on June 21, 2010 ABSTRACT Over the past two decades, the record of South American unenlagiine dromaeosaurids was substantially increased both in quantity as well as in quality of specimens. Here is presented a summary review of the South American record for these theropods. Unenlagia comahuensis, Unenlagia paynemili, and Neuquenraptor argentinus come from the Portezuelo Formation, the former genus being the most complete and with putative avian features. -

Theropod Dinosaurs from Argentina

139 Theropod dinosaurs from Argentina Martín D. EZCURRA1 & Fernando E. NOVAS2 1CONICET, Sección Paleontología Vertebrados, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernardino Rivadavia’, Av. Angel Gallardo 470, Buenos Aires, C1405DJR, Argentina. [email protected], Laboratorio de Anatomía Comparada y Evolución de los Vertebrados, Museo Argentino de Ciencias Naturales ‘Bernardino Rivadavia’, Av. Ángel Gallardo 470, Buenos Aires, C1405DJR, Argentina. [email protected] Abstract. Theropoda includes all the dinosaurs more closely related to birds than to sauropodomorphs (long-necked dinosaurs) and ornithischians (bird-hipped dinosaurs). The oldest members of the group are early Late Triassic in age, and non-avian theropods flourished during the rest of the Mesozoic until they vanished in the Cretaceous-Palaeogene mass extinction. Theropods radiated into two main lineages, Ceratosauria and Tetanurae, which are well represented in Cretaceous rocks from Argentina. Ceratosaurians are the most taxonomically diverse South American non-avian theropods, including small to large-sized species, such as the iconic horned dinosaur Carnotaurus. Argentinean tetanurans are represented by multiple lineages that include some of the largest carnivorous dinosaurs known worldwide (carcharodontosaurids), the enigmatic large-clawed megaraptorans, and small to medium-sized species very closely related to avialans (e.g. unenlagiids). The Argentinean non-avian theropod record has been and is crucial to understand the evolutionary and palaeobiogeographical