Changing Attitudes to Mental Illness in the Australian Defence Force: a Long Way to Go…

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Of the 90 YEARS of the RAAF

90 YEARS OF THE RAAF - A SNAPSHOT HISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY 90 YEARS RAAF A SNAPSHOTof theHISTORY © Commonwealth of Australia 2011 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The views expressed in this work are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of Defence, the Royal Australian Air Force or the Government of Australia, or of any other authority referred to in the text. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry 90 years of the RAAF : a snapshot history / Royal Australian Air Force, Office of Air Force History ; edited by Chris Clark (RAAF Historian). 9781920800567 (pbk.) Australia. Royal Australian Air Force.--History. Air forces--Australia--History. Clark, Chris. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Office of Air Force History. Australia. Royal Australian Air Force. Air Power Development Centre. 358.400994 Design and layout by: Owen Gibbons DPSAUG031-11 Published and distributed by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence PO Box 7935 CANBERRA BC ACT 2610 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 Email: [email protected] Website: www.airforce.gov.au/airpower Chief of Air Force Foreword Throughout 2011, the Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) has been commemorating the 90th anniversary of its establishment on 31 March 1921. -

Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009-2010

Australian War Memorial War Australian Annual Report 2009-2010 Annual Report Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009-2010 Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009–2010 Then Prime Minister of Australia, the Honourable The Council Chair walks with Governor-General Her Excellency Kevin Rudd MP, delivers the Address on ANZAC Ms Quentin Bryce through the Commemorative Area following Day 2010. the 2009 Remembrance Day ceremony. Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009–2010 Annual report for the year ended 30 June 2010, together with the financial statements and the report of the Auditor-General Images produced courtesy of the Australian War Memorial, Canberra Cover image: New Eastern Precinct development at night (AWM PAIU2010/028.11) Back cover image: The sculpture of Sir Edward ‘Weary’ Dunlop overlooks the Terrace at the Memorial cafe (AWM PAIU2010/028.01) Copyright © Australian War Memorial ISSN 1441 4198 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced, copied, scanned, stored in a retrieval system, recorded, or transmitted in any form or by any means without the prior written permission of the publisher. Australian War Memorial GPO Box 345 Canberra, ACT 2601 Australia www.awm.gov.au Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009–2010 iii Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009–2010 iv Australian War Memorial Annual Report 2009–2010 Introduction to the Report The Annual Report of the Australian War Memorial for the year ended 30 June 2010 follows the format for an Annual Report for a Commonwealth Authority in accordance with the Commonwealth Authorities and Companies (CAC) (Report of Operations) Orders 2005 under the CAC Act 1997. -

50 Years of the Strategic and Defence Studies Centre

A NATIONAL ASSET 50 YEARS OF THE STRATEGIC AND DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE A NATIONAL ASSET 50 YEARS OF THE STRATEGIC AND DEFENCE STUDIES CENTRE EDITED BY DESMOND BALL AND ANDREW CARR Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Title: A national asset : 50 years of the Strategic & Defence Studies Centre (SDSC) / editors: Desmond Ball, Andrew Carr. ISBN: 9781760460563 (paperback) 9781760460570 (ebook) Subjects: Australian National University. Strategic and Defence Studies Centre--History. Military research--Australia--History. Other Creators/Contributors: Ball, Desmond, 1947- editor. Carr, Andrew, editor. Dewey Number: 355.070994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover design and layout by ANU Press. This edition © 2016 ANU Press Contents About the Book . vii Contributors . ix Foreword: From 1966 to a Different Lens on Peacemaking . xi Preface . xv Acronyms and Abbreviations . xix List of Plates . xxi 1 . Strategic Thought and Security Preoccupations in Australia . 1 Coral Bell 2 . Strategic Studies in a Changing World . 17 T.B. Millar 3 . Strategic Studies in Australia . 39 J.D.B. Miller 4 . From Childhood to Maturity: The SDSC, 1972–82 . 49 Robert O’Neill 5 . Reflections on the SDSC’s Middle Decades . 73 Desmond Ball 6 . SDSC in the Nineties: A Difficult Transition . 101 Paul Dibb 7 . -

The Sir Richard Williams Foundation

THE SIR RICHARD WILLIAMS FOUNDATION Annual General Meeting Tuesday 22 October 2019 Alastair Swayn Theatre, Brindabella Conference Centre, ACT DRAFT Minutes Meeting opened Air Marshal Geoff Brown AO (Retd), Chair There being a quorum, the Chair declared the meeting open at 1735 hrs. Item 1: Members present, apologies and proxies Air Marshal Geoff Brown AO (Retd), Chair Attendees - 23 VADM (Rtd) Tim Barrett AO CSC RAN AVM Chris Deeble AO, CSC (Retd) Mr Peter Nicholson AO Dr Patrick Bigland WGCDR Tracy Douglas LTCOL Clare O’Neill ACM (Retd) Mark Binskin Mr John Fry Ms Nicole Quinn AIRMSHL (Retd) Geoff Brown AO COL Douglas Mallett AM Mr David Riddel CSC AIRCDRE (Retd) Andrew Campbell AM AIRMSHL (Retd) Errol McCormack AO Mr Michael Walkington AM Mr Robert Carrick AVM Roxley McLennan AO AVM (Retd) Brian Weston AM Mr Brian Cather Mr David Millar Mr Jacob de Wilt Mr Ken Moore Ms Catherine Scott (minutes) Apologies - 41 Mr Satish Ayyalasomayjula AM John Harvey Dr Derek Reinhardt AIRCDRE (Retd) Graham Bentley AM SQNLDR Jenna Higgins SQNLDR Leith Roberts Ms Anne Borzycki Mr Adam Hogan AVM (Retd) Dave Rogers FLTLT Stuart Brown GPCAPT Nick Hogan Mr Terry Saunder AM Mr Colin Cooper Ms Amanda Holt Mr Matthew Sibree AIRCDRE Noel Derwort CSC Mr Ian Irving Mr Michael Spencer Mr Andrew Doyle Mr Stephen Lang Dr Alan Stephens OAM Ms Tracey Friend CDRE(Retd) Geoff Ledger DSC, AM Mr Graeme Swan Mr Vern Gallagher Mr John Lonergan WGCMDR Marcus Watson RADM (Rtd) Raydon Gates AO, CSM Mr David Mahoney Mr Charles Winsor Mr Nicholas Gibbs MAJGEN Fergus 'Gus' McLachlan AO GPCAPT Peter Wood CSM AIRCDRE Darren Goldie AM, CSC Col. -

Australia's Joint Approach Past, Present and Future

Australia’s Joint Approach Past, Present and Future Joint Studies Paper Series No. 1 Tim McKenna & Tim McKay This page is intentionally blank AUSTRALIA’S JOINT APPROACH PAST, PRESENT AND FUTURE by Tim McKenna & Tim McKay Foreword Welcome to Defence’s Joint Studies Paper Series, launched as we continue the strategic shift towards the Australian Defence Force (ADF) being a more integrated joint force. This series aims to broaden and deepen our ideas about joint and focus our vision through a single warfighting lens. The ADF’s activities have not existed this coherently in the joint context for quite some time. With the innovative ideas presented in these pages and those of future submissions, we are aiming to provoke debate on strategy-led and evidence-based ideas for the potent, agile and capable joint future force. The simple nature of ‘joint’—‘shared, held, or made by two or more together’—means it cannot occur in splendid isolation. We need to draw on experts and information sources both from within the Department of Defence and beyond; from Core Agencies, academia, industry and our allied partners. You are the experts within your domains; we respect that, and need your engagement to tell a full story. We encourage the submission of detailed research papers examining the elements of Australian Defence ‘jointness’—officially defined as ‘activities, operations and organisations in which elements of at least two Services participate’, and which is reliant upon support from the Australian Public Service, industry and other government agencies. This series expands on the success of the three Services, which have each published research papers that have enhanced ADF understanding and practice in the sea, land, air and space domains. -

Thesis Title

No Release: A Phenomenological Study of Australian Army Veterans of Afghanistan and Iraq Post-Military Robin Purvis Bachelor of Social Work A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2017 School of Social Science Abstract This study explores the lived post-discharge experience of seven combat veterans of Australia’s Middle East wars. The study has identified there is academic and popular recognition, interest in and knowledge about the process of socialisation into the military. However, there is a noticeable gap in material that explores the process of socialisation out of the military. Eighteen in-depth semi-structured interviews were conducted with the seven participants, some ranging over a twelve-month period. A phenomenological, interpretivist approach was taken using current literature, and input from military advisors, to help contextualise the participants’ stories. Three themes emerged from the study as relevant to understanding the process of transition out of the military: the militarisation of identity, the impact of combat exposure as more deeply embedding the militarised identity and the challenges to this identity in negotiating the liminal space between military world and civilian world. The study identified that the challenges these veterans individually face on exiting the military, and the role their society has, collectively, in assisting their re-entry into the civilian world is not well understood. The study highlights that as well as understanding of the personal challenges these veterans face, the context of social recognition and response is a critical factor in their post-military adjustment in transition. Cultural dissonance, absence of place, unwitting stigma and marginalisation, and societal disavowal were characteristic of the experience of these men in their journey of transition from their military world to achieving re-assimilation in the civilian world. -

Defgram 182/2018 Incoming Defence Senior Leadership Team Announced

UNCONTROLLED IF PRINTED UNCLASSIFIED Department of Defence Active DEFGRAM 182/2018 Issue date: 16 April 2018 Expiry date: 13 July 2018 INCOMING DEFENCE SENIOR LEADERSHIP TEAM ANNOUNCED Incoming Chief of the Defence Force, Vice Chief of the Defence Force, Chief of Navy, Chief of Army and Chief Joint Operations Announced 1. Further to the Prime Minister's press conference, the incoming Defence Senior Leadership Team has now been announced. 2. Lieutenant General Angus Campbell, AO, DSC on promotion to General, will be appointed as the Chief of the Defence Force. Lieutenant General Campbell will be reaching this milestone after 32 years of service with the Australian Regular Army. His extensive military career has included a number of senior roles, such as Head Military Strategic Commitments, Deputy Chief of Army and Commander Joint Agency Task Force. In his current appointment, as Chief of Army, Lieutenant General Campbell has been a driving force in cultural reform, with a specific focus on achieving equal opportunities and addressing domestic violence. His well-respected military career, in addition to his experience working in National Security, for the Department of Prime Minister and Cabinet, make him ideally suited to lead the organisation in further reform and in embedding One Defence. 3. Vice Admiral David Johnston, AO, RAN will be appointed as the Vice Chief of the Defence Force. Vice Admiral Johnston has been serving with the Royal Australian Navy since 1978 and has recently been awarded his Federation Star. His highly esteemed military career has seen him in a number of senior appointments, including Deputy Chief Joint Operations, Commander Border Protection Command and most recently, Chief Joint Operations. -

Report on Abuse at the Australian Defence Force Academy REPORT on ABUSE at the AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE ACADEMY Defence Abuse Response Taskforce

DEFENCE ABUSE RESPONSE TASKFORCE RESPONSE ABUSE DEFENCE DEFENCE ABUSE RESPONSE TASKFORCE Report on abuse at the Australian Defence Force Academy REPORT ON ABUSE AT THE AUSTRALIAN DEFENCE FORCE ACADEMY FORCE DEFENCE AUSTRALIAN THE AT ABUSE ON REPORT DEFENCE ABUSE RESPONSE TASKFORCE Report on abuse at the Australian Defence Force Academy NOVEMBER 2014 ISBN: 978-1-925118-69-8 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 All material presented in this publication is provided under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 Australia licence (www.creativecommons.org/licenses). For the avoidance of doubt, this means this licence only applies to material as set out in this document. The details of the relevant licence conditions are available on the Creative Commons website as is the full legal code for the CC BY 3.0 AU licence (www.creativecommons.org/licenses). Use of the Coat of Arms The terms under which the Coat of Arms can be used are detailed on the It’s an Honour website (www.itsanhonour.gov.au). Contact us Enquiries regarding the licence and any use of this document are welcome at: Commercial and Administrative Law Branch Attorney-General’s Department 3–5 national cct BARTON ACT 2600 Call: 02 6141 6666 Email: [email protected] DEFENCE ABUSE RESPONSE TASKFORCE 26 November 2014 Senator the Hon George Brandis QC Attorney-General PO Box 6100 Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Senator the Hon David Johnston Minister for Defence PO Box 6100 Senate Parliament House CANBERRA ACT 2600 Dear Attorney-General and Minister I am pleased to present the Defence Abuse Response Taskforce (Taskforce) Report on abuse at the Australian Defence Force Academy (ADFA), which provides a detailed discussion of the complaints received by the Taskforce relating to abuse that occurred at ADFA. -

Winning Strategic Competition in the Indo-Pacific

NATIONAL SECURITY FELLOWS PROGRAM Winning Strategic Competition in the Indo-Pacific Jason Begley PAPER SEPTEMBER 2020 National Security Fellowship Program Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs Harvard Kennedy School 79 JFK Street Cambridge, MA 02138 www.belfercenter.org/NSF Statements and views expressed in this report are solely those of the author and do not imply endorsement by Harvard University, Harvard Kennedy School, the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, the U.S. government, the Department of Defense, the Australian Government, or the Department of Defence. Design and layout by Andrew Facini Copyright 2020, President and Fellows of Harvard College Printed in the United States of America NATIONAL SECURITY FELLOWS PROGRAM Winning Strategic Competition in the Indo-Pacific Jason Begley PAPER SEPTEMBER 2020 About the Author A Royal Australian Air Force officer, Jason Begley was a 19/20 Belfer Center National Security Fellow. Trained as a navigator on the P-3C Orion, he has flown multiple intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance opera- tions throughout the Indo-Pacific region and holds Masters degrees from the University of New South Wales and the Australian National University. His tenure as a squadron commander (2014-2017) coincided with the liberation of the Philippines’ city of Marawi from Islamic State, and the South China Sea legal case between the Philippines and the People’s Republic of China. Prior to his Fellowship, he oversaw surveillance, cyber and information operations at Australia’s Joint Operations Command Headquarters, and since returning to Australia now heads up his Air Force’s Air Power Center. Acknowledgements Jason would like to acknowledge the support of the many professors at the Harvard Kennedy School, particularly Graham Allison who also helped him progress his PhD during his Fellowship. -

PART 4 Australian Amphibious Concepts

Edited by Andrew Forbes Edited by the Sea from Combined and Joint Operations Combined and Joint Operations from the Sea Edited by Andrew Forbes DPS MAY038/14 Sea Power centre - australia Combined and Joint Operations from the Sea Proceedings of the Royal Australian Navy Sea Power Conference 2010 © Commonwealth of Australia 2014 This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealing for the purpose of study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, and with the standard Combined and Joint source credit included, no part may be reproduced without written permission. Inquiries should be directed to the Director, Sea Power Centre - Australia. Operations from the Sea The views expressed are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the official policy position of the Australian Government, the Department of Defence and the Royal Australian Proceedings of the Royal Australian Navy Navy. The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort, or Sea Power Conference 2010 otherwise for any statement made in this publication. National Library of Australia - Cataloguing-in-Publication entry: Editor: Forbes, Andrew Robert 1962 - Title: Combined and Joint Operations from the Sea Sub-Title: Proceedings of the Royal Australian Navy Sea Power Conference 2010 ISBN: 978-0-9925004-4-3 Edited by Andrew Forbes Sea Power Centre – Australia The Sea Power Centre - Australia was established to undertake activities to promote the study, Contents discussion and awareness of maritime issues and strategy -

From Controversy to Cutting Edge

From Controversy to Cutting Edge A History of the F-111 in Australian Service Mark Lax © Commonwealth of Australia 2010 This work is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, no part may be reproduced by any process without prior written permission. Inquiries should be made to the publisher. Disclaimer The Commonwealth of Australia will not be legally responsible in contract, tort or otherwise, for any statements made in this document. Release This document is approved for public release. Portions of this document may be quoted or reproduced without permission, provided a standard source credit is included. National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Author: Lax, Mark, 1956- Title: From controversy to cutting edge : a history of the F-111 in Australian service / Mark Lax. ISBN: 9781920800543 (hbk.) Notes: Includes bibliographical references and index. Subjects: Australia. Royal Australian Air Force--History. F-111 (Jet fighter plane)--History. Air power--Australia--History. Dewey Number: 358.43830994 Illustrations: Juanita Franzi, Aero Illustrations Published by: Air Power Development Centre TCC-3, Department of Defence CANBERRA ACT 2600 AUSTRALIA Telephone: + 61 2 6266 1355 Facsimile: + 61 2 6266 1041 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.airpower.gov.au/airpower This book is dedicated to the memory of Air Vice-Marshal Ernie Hey and Dr Alf Payne Without whom, there would have been no F-111C iii Foreword The F-111 has been gracing Australian skies since 1973. While its introduction into service was controversial, it quickly found its way into the hearts and minds of Australians, and none more so than the men and women of Boeing. -

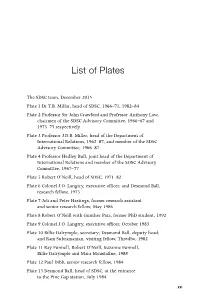

List of Plates

List of Plates The SDSC team, December 2015 Plate 1 Dr T.B. Millar, head of SDSC, 1966–71, 1982–84 Plate 2 Professor Sir John Crawford and Professor Anthony Low, chairmen of the SDSC Advisory Committee, 1966–67 and 1973–75 respectively Plate 3 Professor J.D.B. Miller, head of the Department of International Relations, 1962–87, and member of the SDSC Advisory Committee, 1966–87 Plate 4 Professor Hedley Bull, joint head of the Department of International Relations and member of the SDSC Advisory Committee, 1967–77 Plate 5 Robert O’Neill, head of SDSC, 1971–82 Plate 6 Colonel J.O. Langtry, executive officer, and Desmond Ball, research fellow, 1975 Plate 7 Joli and Peter Hastings, former research assistant and senior research fellow, May 1986 Plate 8 Robert O’Neill with Gunther Patz, former PhD student, 1992 Plate 9 Colonel J.O. Langtry, executive officer, October 1983 Plate 10 Billie Dalrymple, secretary; Desmond Ball, deputy head; and Ram Subramanian, visiting fellow, Thredbo, 1982 Plate 11 Ray Funnell, Robert O’Neill, Suzanne Funnell, Billie Dalrymple and Mara Moustafine, 1988 Plate 12 Paul Dibb, senior research fellow, 1984 Plate 13 Desmond Ball, head of SDSC, at the entrance to the Pine Gap station, July 1984 xxi A NatiONAL ASSeT Plate 14 US President Jimmy Carter and Desmond Ball, April 1985 Plate 15 Desmond Ball and Australian Federation of University Women, Queensland fellow Samina Yasmeen at SDSC, 1985–86 Plate 16 Benjamin Lambeth and Ross Babbage, senior research fellows, and Ray Funnell, July 1986 Plate 17 Mr R.H.