Divorce As Paradigm

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Parshat Acharei-Mot/Kedoshim 5780

Dedicated in memory of Rachel Leah bat R' Chaim Tzvi Volume 12 Number 7 Brought to you by Naaleh.com Parshat Acharei Mot-Kedoshim Productive Planting Based on a Naaleh.com shiur by Mrs. Shira Smiles Summary by Channie Koplowitz-Stein Among the mitzvot in these parshiot is the must we support Torah scholars and our children at the age of three, as they begin mitzvah of orlah. The verses state: “When you institutions when we come to the land. their spiritual awakening. come to the land and you shall plant any fruit Rabbi Y. Salant sees in this connection an tree … for three years [the fruit] shall be affirmation of the relationship between the Asufat Maarachot notes that when Hashem forbidden to you … In the fourth year all its financial support Zevulun is enjoined to give first brought Adam into Gan Eden, he started fruit shall be sanctified to laud Hashem, And Issachar who toils in Torah, the tree of life. Like with chessed. Adam was created without the in the fifth year you may eat the fruit so that it the tithes, orlah or the proceeds from its sale necessity of working for his needs. The trees will increase its crop for you – I am Hashem must be brought to and eaten in Yerushalayim. would provide all his food. Only after the sin your God.” Here the families bringing the gift would be was man forced to work for his bread. immersed in an environment of kedushah, they Altruistic chessed had to precede gevurah and Rabbi S. R. -

Articles About Shidduchim By: Rabbi Yosef Tropper Yoseftropper.Com / [email protected] / 443-535-1232

Articles about Shidduchim by: Rabbi Yosef Tropper YosefTropper.com / [email protected] / 443-535-1232 Table of Contents: The Shidduch Crisis Part 1- Dating Sensitivity The Shidduch Crisis Part 2- Building the Best Match The Shidduch Crisis Part 3- Bridging the Gender Gap A Beautiful Torah Marriage (Part 1 of 2) A Beautiful Torah Marriage (Part 2 of 2) Life Coach- A Torah View The Shidduch Crisis Part 1 – Dating Sensitivity There has been much written about the issue of Shidduchim or lack thereof over the last few years. Many have pointed their fingers at the statistical disproportion between the large number of girls and the shortage of boys. Many have talked about the difference between a “good” boy and a “good” girl. Others have blamed the age differential of when each gender begins dating. Others have claimed that not enough people are getting involved in actually suggesting matches. The list goes on, as we all painfully know. Whichever reason you see as the crux of the matter, there is one issue which I feel compelled to point out here because of its great importance and yet its virtual neglect from public discussion. Perhaps it is this issue which is truly preventing people from coming together. That is: Are the daters doing their part to act with proper care, consideration, and sensitivity towards others? Are they being taught and are they putting into practice how to be the “mentsh” that both girls and boys always state that they are looking for? Disclaimer I hope that we will find ways to enhance the lives of our dear fellow people. -

Halachos of Tefillin One Should Be .ברוך שם

Nissan 5771 Volume I Issue I The point of this publication is to help create an Produced by: Rabbi Avrohom Adler awareness regarding the sanctity of tefillin. של After finishing tightening and positioning the Halachos of Tefillin One should be .ברוך שם... ועד one should say ,ראש by: Rabbi Boruch Hirschfeld Shlit”a is של ראש till the ברוך שם very careful not to say When one puts on tefillin he should have the fully positioned. following things in mind: 1. To fulfill the mitzvah of tefillin shel yad. It is very praiseworthy to learn something while 2. To fulfill the mitzvah of tefillin shel rosh. wearing tefillin, before they are taken off. 3. To subdue my heart, mind and body for Hashem. The Glory of Tefillin 4. To remember the miracle of yetzias by: R’ Zev Busel mitzrayim (shows Hashem’s power over the Yidden - ליהודים היתה אורה ושמחה וששן ויקר .(heaven and earth 5. To minimize the physical pleasures of this experienced light and joy, delight and honor. The world. Gemora in Meseches Megillah tells us that that ,ששון זו מילה ,שמחה זה יום טוב and that ,אורה זו תורה To believe in the Oneness of Hashem .6 Rashi explains that Haman .ויקר אלו תפילין written in the tefillin. and 7. To fulfill everything else written in the decreed against the observance of the tefillin (love Hashem, learn Torah, aforementioned mitzvos and now we are able to mezuzah, tefillah, mitzvos of Pesach and observe them. prohibitions regarding chametz, pidyon haben). The Sfas Emes pondered: If so, why didn't ליהודים היתה תורה יום טוב the passuk just say that The Sfas Emes answers that through ?ומילה ותפילין is while he כוונות The ideal time for thinking these puts on the tefillin. -

The Post Shidduch- Crisis

The Jewish Star Independent and original reporting from the Orthodox communities of Long Island VOL. 8, NO. 44 OCTOBER 30, 2009 | 12 CHESHVAN 5770 www.thejewishstar.com CHALLAH FOR SALE ENDORSEMENTS REVIVING KASZTNER Some say the best in the Five Towns Election Day is Tuesday. Vote! A Holocaust hero finally gets his due? Page 2 Page 11 Page 7 IN MY VIEW Fingerprints, not fingerpaints Elder Rabbi The Post Kamenetzky Shidduch- injured in fall Crisis Suffered concussion; some effects linger BY MAYER FERTIG Rabbi Binyamin Kamenetzky, founder of BY RABBI AVI BILLET Yeshiva of South Shore and many other Five Towns institutions, ur community has a lot to is hospitalized in say about the "shidduch cri- stable condition sis." First, we blame the sin- and described as O gles themselves. Why can't "recovering" after young people date like we did? Why a fall and a blow can't they meet people in normal to the head at the ways? Why can't they have social Sephardic shul on functions like we had? Why can't Peninsula Boule- they get over their hang-ups of dat- vard in ing one person at a time? Why do Cedarhurst. they have to be so picky? Maybe He was there they don't really want to get mar- to borrow a Sefer Photo by Andrew Vardakis ried, because if they did, they Torah for the would. minyan for Sefardi Then we blame their teachers. Meir Heller helps daughter Dina get her fingerprint digitally recorded at the Fingerprinting for Kids fair, held in Cedarhurst’s Maple Plaza on Sunday. -

A Guide to the Observance of Mourning

A GUIDE TO THE OBSERVANCE OF MOURNING (This is a general guide only. For details, consult your rabbi.) Who is a mourner? We are obliged to mourn for a father, mother, son, daughter, brother, sister (including half- brother and half-sister), husband or wife. Males from the age of thirteen years and females the age of twelve years should observe the laws of mourning. While one is permitted to observe mourning rites for others, those who wish to do so should consult their rabbi. Between death and burial During the period between death and burial the mourn known as an omen . The onen is obligated to arrange for the funeral and burial of the dead. In recognition of this obligation and of the mourner's fragile state of mind at this time, the onen is exempt from fulfilling certain other religious duties such as reciting prayers or putting on tefillin, and is not called to the Torah. On Shabbat or a Festival, however, an onen may attend services. Mourner's Kaddish The Kaddish is generally thought of as a prayer for the dead, but it does not mention death or the dead. Reciting Mourner's Kaddish is an act of faith, expressing hope in presence of grief. We praise God with the words of Kaddish, accepting God's sovereignty and affirming life in world. In Jewish tradition, this takes place in public assembly. Thus the Kaddish is recited only in the presence of a minyan. The Mourner's Kaddish is recited for one's parents for eleven months (in some communities for twelve months), counting First and Second Adar, in a leap year, as two separate months. -

Judaism 101 Questions

JUDAISM 101 JUDAISM & GOD 41. Describe a seder plate/table. 1. Define Judaism. 42. What is Shavuot? 2. How is Judaism different from other religions? 43. What is the Counting of the Omer? 3. Describe God? 44. How will you celebrate Shavuot? 4. What is the difference between Askenazim and 45. What is Lag baOmer? Sephardim? 46. What is Yom HaAtzmaut? 5. Explain Suffering. Why do bad things happen 47. What is Sukkot? to good people? 48. Describe a Sukkah. 6. Why do you want to be a Jew? 49. How will you celebrate Sukkot? TORAH & MITZVOT 50. What is a lulav/etrog? 51. Describe a lulav and etrog. 7. What is the Torah? 52. What do you do with a lulav and etrog? 8. Why is Hebrew important? 53. What is Hoshanah Rabbah? 9. Describe a Torah scroll. When do we read Torah? 54. What is Shemini Atzeret? What do we read? 55. What is Simchat Torah? 10. What is important about the Torah? 56. What do we do on these three above holidays? 11. Who wrote the Torah? 57. What is a shofar? 12. Why should we follow the mitzvot? What will 58. What is Selichot? happen if we don’t? What are the Ten Commandments? 59. What is Rosh Hashanah? How many commandments are there? What is a 60. What is the holiest day of the year? Trick mitzvah? question. CHOSEN PEOPLE 61. What are the high holidays? 13. Can a good Jew be a bad person? Why? 62. What are the Yamim Noraim? 14. What does the Chosen People mean to you? 63. -

17. Tzitzit by Rabbi Shraga Simmons How to Gain Some MetaPhysical "Fringe" Benefits

http://www.aish.com/jl/m/mm/Tzitzit.html 17. Tzitzit by Rabbi Shraga Simmons How to gain some metaphysical "fringe" benefits. Tzitzit are tassels that hang down from the four corners of a rectangular garment, as the Torah says: "You shall put fringes on the corners of your garments."1 Why do we wear Tzitzit? The Torah explains that by doing so, "you will see it and remember all the mitzvot."2 How do the tzitzit remind us of the mitzvot? On the simple level, Tzitzit serve as the colloquial stringaroundthefinger reminder.3 As we go about our daily chores, whether at work or at a ball game, Tzitzit give us an anchor to the world of spirituality. Further, the numerical value of "Tzitzit" is 600. Add to that the 8 strings and 5 knots on each corner, and you get 613 – the number of mitzvot in the Torah.4 Let's delve a bit deeper into the verse: "You will see it and remember all the mitzvot." If there are four strings on each corner, why does the Torah use the singular form "it"? "It" refers to the single blue thread on each corner prescribed by the Torah.5 The color blue is similar to the sea, which is like the clear blue sky, which is the color of the God's "heavenly throne."6 Our challenge is to make spirituality a part of daily reality. In seeing the Tzitzit, we have a tangible reminder of an incorporeal God.7 Seeing God in our lives is a progression – from recognizing his presence in mundane things like a garment, all the way to the spiritual realms ("heavenly throne"). -

Opening the Torah to Women: the Transformation of Tradition

Opening the Torah to Women: The Transformation of Tradition Women are a people by themselves -Talmud: Shabbat 62a Traditional Judaism believes that both men and women have differentiated and distinct roles delegated through the Torah. A man’s role is focused on positive time-bound mitzvot (commandments), which include but are not limited to, daily praying, wrapping tefillin and putting on a tallit; whereas a women’s role and mitzvot are not time bound and include lighting Shabbat candles, separating a piece of challah for G-d on Shabbat, and the laws of Niddah (menstruation purity). 1 Orthodox Judaism views the separate roles of men and women as a valued and crucial aspect of Jewish life and law, whereas Jewish feminism and more reform branches of Judaism believe these distinctions between men and women are representative of sexual discrimination and unequal opportunity in Judaism. The creation of the Reform and Conservative movement in the late 1800s paved the way for the rise of the Jewish feminist movement in the 1970s, which re-evaluated the classical Jewish texts and halakha (Jewish law) in relation to the role of women in Judaism. Due to Judaism’s ability to evolve and change throughout time, women associated with different Jewish denominations have been able to create their own place within Judaism while also maintaining the traditional aspects of Judaism in order to find a place which connects them most to their religiosity and femininity as modern Jewish women. In Kabbalah (Jewish mysticism), there is a teaching that states that when each soul is created it contains both a female and male soul. -

Dissenting Opinion on Rabbi Barmash's Responsum on Women and Mitzvot

Dissenting Opinion on Rabbi Barmash’s Responsum on Women and Mitzvot Rabbi Joshua Heller CJLS Iyar 5774 / May 2014 Y.D. 246:6.2014 This paper was submitted, in May 2014, as a dissent to “Women and Mitzvot” by Rabbi Pamela Barmash. Dissenting and Concurring papers are not official positions of the CJLS. I am impressed by Rabbi Barmash’s Teshuvah, and agree with its overall premise, that the status of Jewish women has changed, and continues to change over time, and that halakha must address that reality. This issue goes even beyond the rights of women. Judaism is strengthened by making each adult Jew, male or female, a fully appreciated member of the community, irrespective of gender. Indeed, within our communities we now see that women as a class participate fully in many mitzvot from which they were once considered exempt, as the criteria which may have once mandated those exemptions or exclusions no longer apply. However, I felt compelled to abstain because of two concerns, one general, relating to hiyyuv, obligation, and one specific, relating to tefillin. In particular, I would note that there are strong grounds to consider tefillin differently from the other obligations and practices covered in Rabbi Barmash’s teshuvah. My general concern, shared with a number of my colleagues who have written responses, is that Rabbi Barmash’s focus on obligation may miss the mark. I agree with Rabbi Kalmanofsky that, the language of hiyyuv itself does not adequately capture the way that many in our communities, female and male, approach their lives of religious observance. -

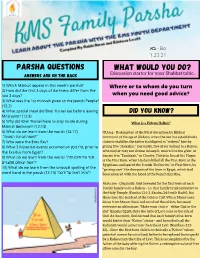

Parsha Questions What Would You Do? Discussion Starter for Your Shabbat Table

Bo - ּבֹא 1.23.21 Parsha Questions What would you do? Discussion starter for your Shabbat table.. Answers are on the back 1) Which Makkot appear in this week's parsha? Where or to whom do you turn 2) How did the first 3 days of darkness differ from the last 3 days? when you need good advice? 3) What was the 1st mitzvah given to the Jewish People? (12:2) 4) What special meal did Bnei Yisrael eat before leaving Did You Know? Mitzrayim? (12:8) 5) Why did Bnei Yisrael have to stay inside during What is a Pidyon HaBen? Makkat Bechorot? (12:13) 6) What do we learn from the words (12:17) OU.org - Redemption of the (First-Born) Son; by Biblical command, at the age of 30 days, when the son has established a "?ושמרתם את המצות" 7) Who were the Erev Rav? claim to viability, the father is obligated to “redeem” him by ,prior to giving five “shekalim,” (currently, five silver dollars) to a Kohen ,ט"ו ִני ָסן What 3 historical events occurred on (8 the Exodus from Egypt? who may or may not choose to keep it, return it to the giver, or donate it to “Tzadakah,” or Charity. This is in lieu of the Plague זכור את־היום הזה" What do we learn from the words (9 of the First Born, when Hashem killed all the First-Born of the ?"אשר יצאתם ממצרים Egyptians, and spared the Jewish “Bechorim,” or First-Born, by 10) What do we learn from the unusual spelling of the “passing over” the doorposts of the Jews in Egypt, which had .been smeared with the blood of the Pesach Sacrifice ?"והיה לאות על־ידכה" (word hand in the pasuk (13:16 Aish.com - Originally, God intended for the first-born of each Jewish family to be a Kohen – i.e. -

“Tefillin Building” Comprehensive Education Outline

“TEFILLIN BUILDING” COMPREHENSIVE EDUCATION OUTLINE Need: Prayer Books Mezuzah & Scroll (Klaf) Open Tefillin & (5) Scrolls Real Tefillin Lesson 1 - What are Tefillin and of Israel, Tefillin do the same for us. Why do we Wear them? 9) “Tefillin” Means “Prayer” – “Prayer Boxes.” Hands On: Writing the Parchment Wear Them On Arm And Head = (students will write the Shema Close To Our Heart And Mind and their name in Hebrew) 10) What Do They Mean? Ever Hear Of 1) Start With The Singing Of The Shema / Kabbalah (Madonna Studies It) – It’s Veahavta And Its Translation Bringing Meaning To The Meaningless, (Pages 100 & 101 In Siddur Sim Shalom) Like Boxes – “Spirituality” – Every Little Part Has Meaning 2) Focus On Words: “You Shall Bind Them As A Sign Upon Your Hand, 11) Take Out Open Tefillin & Show Scrolls They Shall Be A Reminder Above Your Eyes.” 12) Scrolls Mention Tefillin – “Sign Upon Hand…” Mentioned 4 Times In Torah – 3) Open Question: What Is A “Sign”? Show Four Sections For Head And One Section For Arm 4) What Else Is There That We Use In The (One Big Scroll With All 4 Passages) Veahavta? Answer: Mezuzot 13) Show Boxes (“Bayit” = “House”) 5) Show Mezuzah Casing And Shins On Them (Make Sure It Has A Shin On It) 14) Why Shin? Not Shema, But Shadai 6) What Do Mezuzot And Torot (Torahs) – God Protecting Us (Like Our Homes) Have In Common? Answer: Scrolls 15) What’s Different About These Shins? 7) Show Mezuzah Scroll – Show Shema One Shin Has 3 Arms And One Has 4 8) Point Out Shin On Casing – Not For Shema, But Rather For Shadai = God’s 16) Why 3 And 4 Arms? How Many Com- Name Or Shomer Dalatot Yisrael (Shin, mandments Are There? Not 10, But 613 Dalet, Yud) = Guardian Of The Doorposts - Alef = 1, Bet = 2, Gimel = 3, Numerical Out – Everyone Is Responsible for Everyone Else Equivalent Of Shin Is 300 (X2 Shins = 600) - Plus, The Word Sheish (2 Shins) = 6. -

No One Should Interfere: Women and Mitzvat Tzitzit

No One Should Interfere: Women And Mitzvat Tzitzit Vered Noam Translated by Avital Morris The public storm surrounding the Women of the Wall who wear tallitot at the Kotel has been focused primarily on political issues, such as the rights of nonOrthodox people at the Kotel, and throughout this discussion, terms like “Reform,” “Conservative,” “public space,” “provocative” and even “hillul Hashem” (desecration of God’s name) have been thrown around. But before we engage in politics, let’s study Torah, and follow the interesting relationship woven (in more than one sense) throughout the ages between Jewish women and the mitzvah of tzitzit. A. The Tannaitic Period: Women, Too מצוות עשה שהזמן) The Mishnah in Kiddushin exempts women from positive timebound commandments and a baraita quoted in the gemara on that mishnah lists the mitzvah of tzitzit, which applies ,(גרמא during the day but not at night, as an example of mitzvot in that category (Kiddushin 33b34a): איזוהי מצות עשה שהזמן גרמא? סוכה, ולולב, שופר, וציצית Which are the positive timebound ותפילין. commandments? Sukkah and lulav, shofar, and tzitzit and tefillin. However, many people do not know that this baraita represents a minority opinion, that of Rabbi Shimon, and not the majority of the rabbis of the Mishnah. Opposed to it stand no fewer than four tannaitic statements ruling according to the majority opinion, that women are obligated in the mitzvah of tzitzit; it therefore appears that most of the women in tannaitic society did fulfill this mitzvah. Tosefta Kiddushin 1:10 lists tzitzit as a positive mitzvah that is not timebound, in which women are therefore obligated: 1.