Program and Abstracts

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Comment on Beowulf : Gutarnas Nationalepos by Tore Gannholm

A comment on Beowulf : gutarnas nationalepos by Tore Gannholm Rausing, Gad Fornvännen 1995:1, 50-53 http://kulturarvsdata.se/raa/fornvannen/html/1995_050 Ingår i: samla.raa.se 50 Debatt A Comment on Beowulf- Gutarnas nationalepos by Tore Gannholm Together with Widsid the Lay of Beowulf is the his ancestors' gestae alive in a society depend- oldest of the surviving Norse poems. Even ing on the spöken word for its history. It is though translated several times it has long been extremely unlikely that any 9th-century Norse- out of print, as has the Gutasaga. Since they are man or Anglosaxon wrote "historical fiction", both important to our understanding of Norse fiction in the sense that the characters and the society in the Migration Age the new edition, events described were the produets of the "au- prepared by Tore Gannholm, is welcome in thor's" imagination. Having been composed for deed. Tore Gannholm is to be congratulated for a definite purpose the Sagas must be taken having achieved this, the following comments seriously and read critically. Their factual in in no way detracting from the importance of his formation must be taken seriously. Doing so, work. Tore Gannholm attempts to fit the Lay of Beo It seems that the Norse royal families and wulf and the heroes' actions into the history of also those of the local magnates each had a Gotland and Denmark. "family saga", listing the ancestors and their In his introduction Gannholm reminds us most important deeds, and that each of these that we still suffer badly from earlier genera sagas may have formed a "register" to a series tions' "Swedish-centered" historical research. -

Celtic Solar Goddesses: from Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven

CELTIC SOLAR GODDESSES: FROM GODDESS OF THE SUN TO QUEEN OF HEAVEN by Hayley J. Arrington A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Women’s Spirituality Institute of Transpersonal Psychology Palo Alto, California June 8, 2012 I certify that I have read and approved the content and presentation of this thesis: ________________________________________________ __________________ Judy Grahn, Ph.D., Committee Chairperson Date ________________________________________________ __________________ Marguerite Rigoglioso, Ph.D., Committee Member Date Copyright © Hayley Jane Arrington 2012 All Rights Reserved Formatted according to the Publication Manual of the American Psychological Association, 6th Edition ii Abstract Celtic Solar Goddesses: From Goddess of the Sun to Queen of Heaven by Hayley J. Arrington Utilizing a feminist hermeneutical inquiry, my research through three Celtic goddesses—Aine, Grian, and Brigit—shows that the sun was revered as feminine in Celtic tradition. Additionally, I argue that through the introduction and assimilation of Christianity into the British Isles, the Virgin Mary assumed the same characteristics as the earlier Celtic solar deities. The lands generally referred to as Celtic lands include Cornwall in Britain, Scotland, Ireland, Wales, and Brittany in France; however, I will be limiting my research to the British Isles. I am examining these three goddesses in particular, in relation to their status as solar deities, using the etymologies of their names to link them to the sun and its manifestation on earth: fire. Given that they share the same attributes, I illustrate how solar goddesses can be equated with goddesses of sovereignty. Furthermore, I examine the figure of St. -

Universal Mythology: Stories

Universal Mythology: Stories That Circle The World Lydia L. This installation is about mythology and the commonalities that occur between cultures across the world. According to folklorist Alan Dundes, myths are sacred narratives that explain the evolution of the world and humanity. He defines the sacred narratives as “a story that serves to define the fundamental worldview of a culture by explaining aspects of the natural world, and delineating the psychological and social practices and ideals of a society.” Stories explain how and why the world works and I want to understand the connections in these distant mythologies by exploring their existence and theories that surround them. This painting illustrates the connection between separate cultures through their polytheistic mythologies. It features twelve deities, each from a different mythology/religion. By including these gods, I have allowed for a diversified group of cultures while highlighting characters whose traits consistently appear in many mythologies. It has the Celtic supreme god, Dagda; the Norse trickster god, Loki; the Japanese moon god, Tsukuyomi; the Aztec sun god, Huitzilopochtli; the Incan nature goddess, Pachamama; the Egyptian water goddess, Tefnut; the Polynesian fire goddess, Mahuika; the Inuit hunting goddess, Arnakuagsak; the Greek fate goddesses, the Moirai: Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos; the Yoruba love goddess, Oshun; the Chinese war god, Chiyou; and the Hindu death god, Yama. The painting was made with acrylic paint on mirror. Connection is an important element in my art, and I incorporate this by using the mirror to bring the audience into the piece, allowing them to see their reflection within the parting of the clouds, whilst viewing the piece. -

Chapter 3 Quiz What Lead to Joseph Campbell's Interest in Comparative

Chapter 3 Quiz What lead to Joseph Campbell's interest in comparative mythology? When Campbell was a child, he became fascinated with Native American Culture. This led him to a lifelong passion for myth and storytelling. When Campbell was studying maths and biology, he recognized that he is inclined towards humanities. Soon he became an English literature student at Columbia University. Campbell was interested in knowledge above all else. In 1924 Campbell traveled to Europe with his family. On the ship during his return trip, he encountered the Messiah elect of the Theosophical Society, Jiddu Krishnamurti. They discussed Indian philosophy which leads to Campbell’s interest in Hindu and Indian philosophy. Campbell studied Old French, Provencal and Sanskrit at the University of Paris and the University of Munich in Germany. He learned to read and speak French and German. When Campbell did not have any work after his graduation (in depression era), he used to read nine hours a day for five years. He soon discovered the works of Carl Jung who is the founder of analytical psychology. Campbell could recognize recurring patterns of all the stories he had read, from Carl Jung’s work. This must have encouraged Joseph Campbell in comparative mythology. How did Joseph Campbell become the world's foremost scholar on mythology? How did the Great Depression benefit his education? Joseph Campbell received BA in English literature and MA in Medieval literature from Columbia University. Campbell also received a fellowship from Columbia University to study in Europe. He studied Old French, Provencal and Sanskrit at the University of Paris and the University of Munich in Germany. -

ON the GODS of GREECE, ITALY, and INDIA Phiroze Vasunia a New Form of Cultural Cosmopolitanism

NATIONALISM AND COSMOPOLITANISM: ON THE GODS OF GREECE, ITALY, AND INDIA Phiroze Vasunia A new form of cultural cosmopolitanism arose in Europe, in the second half of the eighteenth century, partly as a consequence of the Enlightenment and partly as the result of an increased colonial presence in Asia. One of its most illustrious and influential exponents was William Jones, the linguist, translator, and judge for the East India Company in Calcutta. His lecture ‘On the Gods of Greece, Italy, and India’, written in 1784 and subsequently revised, offers a perspective on myth that is supple, flexible, and wide-ranging. It appeared some time before his famous statement about the kinship of languages, in the Third Anniversary Discourse of February 1786, and anticipates some of the conclusions at which he arrived later still. In fact, Jones’ writings in the months and years before the celebrated discourse of 1786, are already pointing to connections and syntheses across cultures; they offer a conception of mythological and religious contact that is startling in its openness and far removed from the parochialism of numerous contemporaries. Jones’ work demonstrates that a cosmopolitan and transnational recuperation of the ancient narratives exists alongside national or nationalist readings of myth. The emergence of the nation state in the eighteenth century gave a new urgency to the idea and the actuality of the nation and, thus, also an important new context to the relationship between nation and myth. The Founding Fathers and other colonial Americans argued vehemently about the meaning of the story of Aeneas and the establishment of Rome. -

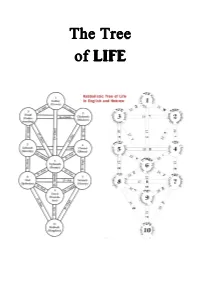

The Tree of LIFE

The Tree of LIFE ~ 2 ~ ~ 3 ~ ~ 4 ~ Trees of Life. From the highest antiquity trees were connected with the gods and mystical forces in nature. Every nation had its sacred tree, with its peculiar characteristics and attributes based on natural, and also occasionally on occult properties, as expounded in the esoteric teachings. Thus the peepul or Âshvattha of India, the abode of Pitris (elementals in fact) of a lower order, became the Bo-tree or ficus religiosa of the Buddhists the world over, since Gautama Buddha reached the highest knowledge and Nirvâna under such a tree. The ash tree, Yggdrasil, is the world-tree of the Norsemen or Scandinavians. The banyan tree is the symbol of spirit and matter, descending to the earth, striking root, and then re-ascending heavenward again. The triple- leaved palâsa is a symbol of the triple essence in the Universe - Spirit, Soul, Matter. The dark cypress was the world-tree of Mexico, and is now with the Christians and Mahomedans the emblem of death, of peace and rest. The fir was held sacred in Egypt, and its cone was carried in religious processions, though now it has almost disappeared from the land of the mummies; so also was the sycamore, the tamarisk, the palm and the vine. The sycamore was the Tree of Life in Egypt, and also in Assyria. It was sacred to Hathor at Heliopolis; and is now sacred in the same place to the Virgin Mary. Its juice was precious by virtue of its occult powers, as the Soma is with Brahmans, and Haoma with the Parsis. -

On Program and Abstracts

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & MASARYK UNIVERSITY, BRNO, CZECH REPUBLIC TENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY TIME AND MYTH: THE TEMPORAL AND THE ETERNAL PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 26-28, 2016 Masaryk University Brno, Czech Republic Conference Venue: Filozofická Fakulta Masarykovy University Arne Nováka 1, 60200 Brno PROGRAM THURSDAY, MAY 26 08:30 – 09:00 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:00 – 09:30 OPENING ADDRESSES VÁCLAV BLAŽEK Masaryk University, Brno, Czech Republic MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA; IACM THURSDAY MORNING SESSION: MYTHOLOGY OF TIME AND CALENDAR CHAIR: VÁCLAV BLAŽEK 09:30 –10:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography & European University, St. Petersburg, Russia OLD WOMAN OF THE WINTER AND OTHER STORIES: NEOLITHIC SURVIVALS? 10:00 – 10:30 WIM VAN BINSBERGEN African Studies Centre, Leiden, the Netherlands 'FORTUNATELY HE HAD STEPPED ASIDE JUST IN TIME' 10:30 – 11:00 LOUISE MILNE University of Edinburgh, UK THE TIME OF THE DREAM IN MYTHIC THOUGHT AND CULTURE 11:00 – 11:30 Coffee Break 11:30 – 12:00 GÖSTA GABRIEL Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, Germany THE RHYTHM OF HISTORY – APPROACHING THE TEMPORAL CONCEPT OF THE MYTHO-HISTORIOGRAPHIC SUMERIAN KING LIST 2 12:00 – 12:30 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia CULTIC CALENDAR AND PSYCHOLOGY OF TIME: ELEMENTS OF COMMON SEMANTICS IN EXPLANATORY AND ASTROLOGICAL TEXTS OF ANCIENT MESOPOTAMIA 12:30 – 13:00 ATTILA MÁTÉFFY Hacettepe University, Ankara, Turkey & Georg-August-Universität Göttingen, -

Aztec Mythology

Aztec Mythology One of the main things that must be appreciated about Aztec mythology is that it has both similarities and differences to European polytheistic religions. The idea of what a god was, and how they acted, was not the same between the two cultures. Along with all other native American religions, the Aztec faith developed from the Shamanism brought by the first migrants over the Bering Strait, and developed independently of influences from across the Atlantic (and Pacific). The concept of dualism is one that students of Chinese religions should be aware of; the idea of balance was primary in this belief system. Gods were not entirely good or entirely bad, being complex characters with many different aspects and their own desires and motivations. This is highlighted by the relation between Quetzalcoatl and Tezcatlipoca. When the Spanish arrived with their European sensibilities, they were quick to name one good and one evil, identifying Quetzalcoatl with Christ and Tezcatlipoca with Satan during their attempts to integrate the Nahua peoples into Christianity. But to the Aztecs neither god would have been “better” than the other; they are just different and opposing sides of the same duality. Indeed, their identities are rather nebulous, with Quetzalcoatl often being referred to as “White Tezcatlipoca” and Tezcatlipoca as “Black Quetzalcoatl”. The Mexica, as is explained in the history section, came from North of Mexico in a location they named “Aztlan” (from which Europeans developed the term Aztec). During their migration south they were exposed to and assimilated elements of several native religions, including those of the Toltecs, Mayans, and Zapotecs. -

M. Witzel (2003) Sintashta, BMAC and the Indo-Iranians. a Query. [Excerpt

M. Witzel (2003) Sintashta, BMAC and the Indo-Iranians. A query. [excerpt from: Linguistic Evidence for Cultural Exchange in Prehistoric Western Central Asia] (to appear in : Sino-Platonic Papers 129) Transhumance, Trickling in, Immigration of Steppe Peoples There is no need to underline that the establishment of a BMAC substrate belt has grave implications for the theory of the immigration of speakers of Indo-Iranian languages into Greater Iran and then into the Panjab. By and large, the body of words taken over into the Indo-Iranian languages in the BMAC area, necessarily by bilingualism, closes the linguistic gap between the Urals and the languages of Greater Iran and India. Uralic and Yeneseian were situated, as many IIr. loan words indicate, to the north of the steppe/taiga boundary of the (Proto-)IIr. speaking territories (§2.1.1). The individual IIr. languages are firmly attested in Greater Iran (Avestan, O.Persian, Median) as well as in the northwestern Indian subcontinent (Rgvedic, Middle Vedic). These materials, mentioned above (§2.1.) and some more materials relating to religion (Witzel forthc. b) indicate an early habitat of Proto- IIr. in the steppes south of the Russian/Siberian taiga belt. The most obvious linguistic proofs of this location are the FU words corresponding to IIr. Arya "self-designation of the IIr. tribes": Pre-Saami *orja > oarji "southwest" (Koivulehto 2001: 248), ārjel "Southerner", and Finnish orja, Votyak var, Syry. ver "slave" (Rédei 1986: 54). In other words, the IIr. speaking area may have included the S. Ural "country of towns" (Petrovka, Sintashta, Arkhaim) dated at c. -

Światowit. Volume LVII. World Archaeology

Światowit II LV WIATOWIT S ´ VOLUME LVII WORLD ARCHAEOLOGY Swiatowit okl.indd 2-3 30/10/19 22:33 Światowit XIII-XIV A/B_Spis tresci A 07/11/2018 21:48 Page I Editorial Board / Rada Naukowa: Kazimierz Lewartowski (Chairman, Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Serenella Ensoli (University of Campania “Luigi Vanvitelli”, Italy), Włodzimierz Godlewski (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Joanna Kalaga ŚŚwiatowitwiatowit (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland), Mikola Kryvaltsevich (Department of Archaeology, Institute of History, National Academy of Sciences of Belarus, Belarus), Andrey aannualnnual ofof thethe iinstitutenstitute ofof aarchaeologyrchaeology Mazurkevich (Department of Archaeology of Eastern Europe and Siberia, The State Hermitage ofof thethe uuniversityniversity ofof wwarsawarsaw Museum, Russia), Aliki Moustaka (Department of History and Archaeology, Aristotle University of Thesaloniki, Greece), Wojciech Nowakowski (Institute of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, ocznikocznik nstytutunstytutu rcheologiircheologii Poland), Andreas Rau (Centre for Baltic and Scandinavian Archaeology, Schleswig, Germany), rr ii aa Jutta Stroszeck (German Archaeological Institute at Athens, Greece), Karol Szymczak (Institute uuniwersytetuniwersytetu wwarszawskiegoarszawskiego of Archaeology, University of Warsaw, Poland) Volume Reviewers / Receznzenci tomu: Jacek Andrzejowski (State Archaeological Museum in Warsaw, Poland), Monika Dolińska (National Museum in Warsaw, Poland), Arkadiusz -

Ritual Details of the Irish Horse Sacrifice in Betha Mholaise Daiminse

Ritual Details of the Irish Horse Sacrifice in Betha Mholaise Daiminse David Fickett-Wilbar Durham, New Hampshire [email protected] The kingly inauguration ritual described by Gerald of Wales has often been compared with horse sacrifice rituals in other Indo-European traditions, in particular the Roman October Equus and the Vedic aßvamedha. Among the doubts expressed about the Irish account is that it is the only text that describes the ritual. I will argue, however, that a similar ritual is found in another text, the Irish Life of St. Molaise of Devenish (Betha Mholaise Daiminise), not only confirming the accuracy of much of Gerald’s account, but providing additional details. Gerald of Wales’ (Gerald Cambrensis’) description of “a new and outlandish way of confirming kingship and dominion” in Ireland is justly famous among Celticists and Indo-European comparativists. It purports to give us a description of what can only be a pagan ritual, accounts of which from Ireland are in short supply, surviving into 12th century Ireland. He writes: Est igitur in boreali et ulteriori Uitoniae parte, scilicet apud Kenelcunnil, gens quaedam, quae barbaro nimis et abominabili ritu sic sibi regem creare solet. Collecto in unum universo terrae illius populo, in medium producitur jumentum candidum. Ad quod sublimandus ille non in principem sed in beluam, non in regem sed exlegem, coram omnibus bestialiter accedens, non minus impudenter quam imprudenter se quoque bestiam profitetur. Et statim jumento interfecto, et frustatim in aqua decocto, in eadam aqua balneum ei paratur. Cui insidens, de carnibus illis sibi allatis, circumstante populo suo et convescente, comedit ipse. -

Sources of Mythology: National and International

INTERNATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY & EBERHARD KARLS UNIVERSITY, TÜBINGEN SEVENTH ANNUAL INTERNATIONAL CONFERENCE ON COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY SOURCES OF MYTHOLOGY: NATIONAL AND INTERNATIONAL MYTHS PROGRAM AND ABSTRACTS May 15-17, 2013 Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany Conference Venue: Alte Aula Münzgasse 30 72070, Tübingen PROGRAM WEDNESDAY, MAY 15 08:45 – 09:20 PARTICIPANTS REGISTRATION 09:20 – 09:40 OPENING ADDRESSES KLAUS ANTONI Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany JÜRGEN LEONHARDT Dean, Faculty of Humanities, Eberhard Karls University, Tübingen, Germany 09:40 – 10:30 KEYNOTE LECTURE MICHAEL WITZEL Harvard University, USA MARCHING EAST, WITH A DETOUR: THE CASES OF JIMMU, VIDEGHA MATHAVA, AND MOSES WEDNESDAY MORNING SESSION CHAIR: BORIS OGUIBÉNINE GENERAL COMPARATIVE MYTHOLOGY AND METHODOLOGY 10:30 – 11:00 YURI BEREZKIN Museum of Anthropology and Ethnography, Saint Petersburg, Russia UNNOTICED EURASIAN BORROWINGS IN PERUVIAN FOLKLORE 11:00 – 11:30 EMILY LYLE University of Edinburgh, UK THE CORRESPONDENCES BETWEEN INDO-EUROPEAN AND CHINESE COSMOLOGIES WHEN THE INDO-EUROPEAN SCHEME (UNLIKE THE CHINESE ONE) IS SEEN AS PRIVILEGING DARKNESS OVER LIGHT 11:30 – 12:00 Coffee Break 12:00 – 12:30 PÁDRAIG MAC CARRON RALPH KENNA Coventry University, UK SOCIAL-NETWORK ANALYSIS OF MYTHOLOGICAL NARRATIVES 2 NATIONAL MYTHS: NEAR EAST 12:30 – 13:00 VLADIMIR V. EMELIANOV St. Petersburg State University, Russia FOUR STORIES OF THE FLOOD IN SUMERIAN LITERARY TRADITION 13:00 – 14:30 Lunch Break WEDNESDAY AFTERNOON SESSION CHAIR: YURI BEREZKIN NATIONAL MYTHS: HUNGARY AND ROMANIA 14:30 – 15:00 ANA R. CHELARIU New Jersey, USA METAPHORS AND THE DEVELOPMENT OF MYTHICAL LANGUAGE - WITH EXAMPLES FROM ROMANIAN MYTHOLOGY 15:00 – 15:30 SAROLTA TATÁR Peter Pazmany Catholic University of Hungary A PECHENEG LEGEND FROM HUNGARY 15:30 – 16:00 MARIA MAGDOLNA TATÁR Oslo, Norway THE MAGIC COACHMAN IN HUNGARIAN TRADITION 16:00 – 16:30 Coffee Break NATIONAL MYTHS: AUSTRONESIA 16:30 – 17:00 MARIA V.