From Exclusionary to Restorative: an Intentional, Trauma-Sensitive

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Excesss Karaoke Master by Artist

XS Master by ARTIST Artist Song Title Artist Song Title (hed) Planet Earth Bartender TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIM ? & The Mysterians 96 Tears E 10 Years Beautiful UGH! Wasteland 1999 Man United Squad Lift It High (All About 10,000 Maniacs Candy Everybody Wants Belief) More Than This 2 Chainz Bigger Than You (feat. Drake & Quavo) [clean] Trouble Me I'm Different 100 Proof Aged In Soul Somebody's Been Sleeping I'm Different (explicit) 10cc Donna 2 Chainz & Chris Brown Countdown Dreadlock Holiday 2 Chainz & Kendrick Fuckin' Problems I'm Mandy Fly Me Lamar I'm Not In Love 2 Chainz & Pharrell Feds Watching (explicit) Rubber Bullets 2 Chainz feat Drake No Lie (explicit) Things We Do For Love, 2 Chainz feat Kanye West Birthday Song (explicit) The 2 Evisa Oh La La La Wall Street Shuffle 2 Live Crew Do Wah Diddy Diddy 112 Dance With Me Me So Horny It's Over Now We Want Some Pussy Peaches & Cream 2 Pac California Love U Already Know Changes 112 feat Mase Puff Daddy Only You & Notorious B.I.G. Dear Mama 12 Gauge Dunkie Butt I Get Around 12 Stones We Are One Thugz Mansion 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simon Says Until The End Of Time 1975, The Chocolate 2 Pistols & Ray J You Know Me City, The 2 Pistols & T-Pain & Tay She Got It Dizm Girls (clean) 2 Unlimited No Limits If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 20 Fingers Short Dick Man If You're Too Shy (Let Me 21 Savage & Offset &Metro Ghostface Killers Know) Boomin & Travis Scott It's Not Living (If It's Not 21st Century Girls 21st Century Girls With You 2am Club Too Fucked Up To Call It's Not Living (If It's Not 2AM Club Not -

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 037 537 VT 010 080 Southern Illinois Univ., Carbondale. Center for the Study of Crime, Delinquency and Correc

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 037 537 VT 010 080 TITLE Development Laboratory for Cos:rectional Training* Final Report. INSTITUTION Southern Illinois Univ., Carbondale. Center for the Study of Crime, Delinquency and Corrections. SI,ONS AGENCY Department of Justice, Washington, D.C. Office of Law Enforcement Assistance. PUB DATE Sep 68 NOTE 143p. AVAILABLE FROM Center for the Study of Crime, Delinquency, and Corrections; Southern Illinois University, Carbondale, Illinois 62901 ($1.50) EDRS PRICE EDRS Price MF $0.75 HC-$7.25 DESCRIPTORS *Correctional Rehabilitation, Curriculum Guides, *Evaluation, Followup Studies, *Inservice Programs, *Institutes (Training Programs), *Instructional Staff, Tests ABSTRACT This laboratory and research center for the training of correctional officers and personnel developed a program to provide: (1) a substantive framework of knowledge,(2) intensive training in learning principles, Luman behavior, communication procedures, and teaching techniques, and (3)practice in teaching under supervision for the in-service training of prison personnel. Curriculum was developed for a 9-week institute which included training curriculum, student teaching, and administrative support. A thorough examination uf the institute was one of the main features of the program, which was attended by representatives of 14 states. A written evaluation was made by trainers, correctional officers, and management, and a followup study in the field evaluated the impact of the program on the various correctional institutions. Both evaluations showed that the program was beneficial, and the followup study illustrated that the institute did have an impact on prison training programs. (BC) /0.5'P1/1. '$1.50 FINAL E DEVELOPMENTAL LABORATORY FOR CORRECTIONAL TRAINING U. S. DEPARTMENT OF JUSTICE GRANT NO. -

Task-Space Admittance Controller with Adaptive Inertia Matrix Conditioning

Journal of Intelligent & Robotic Systems (2021) 101: 41 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10846-020-01275-0 Task-Space Admittance Controller with Adaptive Inertia Matrix Conditioning Mariana de Paula Assis Fonseca1 · Bruno Vilhena Adorno2 · Philippe Fraisse3 Received: 1 July 2020 / Accepted: 8 October 2020 / Published online: 4 February 2021 © The Author(s) 2021 Abstract Whenrobots physically interact with the environment, compliant behaviors should be imposed to prevent damages to all entities involved in the interaction. Moreover, during physical interactions, appropriate pose controllers are usually based on the robot dynamics, in which the ill-conditioning of the joint-space inertia matrix may lead to poor performance or even instability. When the control is not precise, large interaction forces may appear due to disturbed end-effector poses, resulting in unsafe interactions. To overcome these problems, we propose a task-space admittance controller in which the inertia matrix conditioning is adapted online. To this end, the control architecture consists of an admittance controller in the outer loop, which changes the reference trajectory to the robot end-effector to achieve a desired compliant behavior; and an adaptive inertia matrix conditioning controller in the inner loop to track this trajectory and improve the closed- loop performance. We evaluated the proposed architecture on a KUKA LWR4+ robot and compared it, via rigorous statistical analyses, to an architecture in which the proposed inner motion controller was replaced by two widely used ones. The admittance controller with adaptive inertia conditioning presents better performance than with a controller based on the inverse dynamics with feedback linearization, and similar results when compared to the PID controller with gravity compensation in the inner loop. -

8123 Songs, 21 Days, 63.83 GB

Page 1 of 247 Music 8123 songs, 21 days, 63.83 GB Name Artist The A Team Ed Sheeran A-List (Radio Edit) XMIXR Sisqo feat. Waka Flocka Flame A.D.I.D.A.S. (Clean Edit) Killer Mike ft Big Boi Aaroma (Bonus Version) Pru About A Girl The Academy Is... About The Money (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug About The Money (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. feat. Young Thug, Lil Wayne & Jeezy About Us [Pop Edit] Brooke Hogan ft. Paul Wall Absolute Zero (Radio Edit) XMIXR Stone Sour Absolutely (Story Of A Girl) Ninedays Absolution Calling (Radio Edit) XMIXR Incubus Acapella Karmin Acapella Kelis Acapella (Radio Edit) XMIXR Karmin Accidentally in Love Counting Crows According To You (Top 40 Edit) Orianthi Act Right (Promo Only Clean Edit) Yo Gotti Feat. Young Jeezy & YG Act Right (Radio Edit) XMIXR Yo Gotti ft Jeezy & YG Actin Crazy (Radio Edit) XMIXR Action Bronson Actin' Up (Clean) Wale & Meek Mill f./French Montana Actin' Up (Radio Edit) XMIXR Wale & Meek Mill ft French Montana Action Man Hafdís Huld Addicted Ace Young Addicted Enrique Iglsias Addicted Saving abel Addicted Simple Plan Addicted To Bass Puretone Addicted To Pain (Radio Edit) XMIXR Alter Bridge Addicted To You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Avicii Addiction Ryan Leslie Feat. Cassie & Fabolous Music Page 2 of 247 Name Artist Addresses (Radio Edit) XMIXR T.I. Adore You (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miley Cyrus Adorn Miguel Adorn Miguel Adorn (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel Adorn (Remix) Miguel f./Wiz Khalifa Adorn (Remix) (Radio Edit) XMIXR Miguel ft Wiz Khalifa Adrenaline (Radio Edit) XMIXR Shinedown Adrienne Calling, The Adult Swim (Radio Edit) XMIXR DJ Spinking feat. -

Drake Worst Behaviour Free Download Mp3

Drake worst behaviour free download mp3 LINK TO DOWNLOAD Drake Worst Behavior mp3 download free. Download Waptrick Drake albums. Drake Worst Behavior Mp3 Download. Download Worst Behavior mp3 Mp3, best quality, Mb. Download Worst Behavior mp3 Mp3, standard quality, Mb. Download Worst Behavior mp3 Mp3, low quality, Mb. Related Pages. Sep 23, · Worst Behavior MP3 Song by Drake from the album Nothing Was The Same (Deluxe). Download Worst Behavior song on renuzap.podarokideal.ru and listen Nothing Was The Same (Deluxe) Worst Behavior song offline. Drake Worst Behavior free mp3 download and stream. Drake – Worst Behavior Download Mp3. Drake release new single dubbed “Worst behavior”.. Enjoy!! Listen Up & Download Drake – Worst Behavior Mp3 Below: Download Drake – Worst Behavior Mp3. Sep 16, · Drake publishes this new record titled Worst Behavior. Produced by DJ Dahi. Изтегли безплатно Мп3 песента Drake - Worst Behavior Free Download MP3 Хитовете са тук! CDRip New Музика Drake - Worst Behavior. 27 Март - # Hip-Hop,R`n`B. Прегледано: път. Drake Worst Behavior Mp3 indir dur müzik yükle Worst Behavior dinle sözleri oku, Worst Behavior cepten mobil indir. Mp3 indir müzik yükle şarkı listesi oluştur. May 18, · Album: Drake – Nothing Was The Same () Stream And “Listen to Album: Drake – Nothing Was The Same ()” “fakaza Mp3” kbps flexyjam cdq itunes Fakaza download datafilehost Descarger torrent zippyshare download Song. Download Song 2 March 26, Love Me. Drake, Future, Lil Wayne Worst Behavior - Drake Download this track All Me - Drake, 2 Chainz, Big Sean Free Spirit - Drake, Rick Ross Download this track Girls Love Beyoncé. Waptrick Drake Worst renuzap.podarokideal.ru3 Free Download. -

Workplace Experience 10 Rules for Mastering Disruption in Recruiting and Engaging Employees

THE FUTURE WORKPLACE EXPERIENCE 10 RULES FOR MASTERING DISRUPTION IN RECRUITING AND ENGAGING EMPLOYEES JEANNE C. MEISTER KEVIN J. MULCAHY Bonus Material Meister 00.indd 3 9/6/16 10:41 AM Figure I.1 Ten rules to navigate the future workplace HOW THE CHANGING WHAT WORKERS TECHNOLOGY COMPOSITION EXPECT FROM TRANSFORMS OF THE WORK THE WORKPLACE WORKFORCE Rule #1: Make the Rule #4: Consider Rule #7: Tap the Power Workplace an Technology an of Multiple Generations Experience Enabler and Disruptor Rule #8: Build Rule #5: Build a Gender Equality Rule #2: Use Space Data-Driven Recruiting to Promote Culture Ecosystem Rule #9: Plan for More Gig Economy Workers Rule #3: Be an Rule #6: Embrace Rule #10: Be a Agile Leader On-Demand Learning Workplace Activist Source: Future Workplace Meister 00.indd 18 9/6/16 10:41 AM Table 1.1 Samples of Global Employer Rating Sites Employer Rating Site Country Focus Website Tag Line JobAdvisor.com.au Australia Cultural match “Find your dream employer” RateMyEmployer.ca Canada Employer ratings “Who said background checks and and rankings Pre-Employment Screenings should be reserved for employers only?” Kununu.com Germany Employer rating and “Complete transparency in the job job listing platform market” TheJobCrowd.com United Focused on recent “Graduate Employers. Reviewed by Kingdom graduates their Graduate Employees” Glassdoor.com USA Employer and CEO “To help people everywhere find jobs ratings and reviews and companies they love” Meister 01.indd 6 9/6/16 10:41 AM Figure 1.1 The Future Workplace Experience I Flexibility -

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P

Ordered by ARTIST 1 SONG NO TITLE ARTIST 5587 - 16 Blackout (Hed) P. E. 5772 - 15 Caught Up In You .38 Special 5816 - 08 Hold On Loosely .38 Special 5772 - 08 If I'd Been The One .38 Special 5950 - 06 Second Chance .38 Special 4998 - 05 Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation 4998 - 06 While We're Young 1 Girl Nation 5915 - 18 Beautiful 10 Years 5881 - 11 Through The Iris 10 Years 6085 - 15 Wasteland 10 Years 5459 - 07 Because The Night 10,000 Maniacs 5218 - 08 Candy Everybody Wants 10,000 Maniacs 1046A -08 These Are Days 10,000 Maniacs 5246 - 14 I'm Not In Love 10cc 6274 - 20 Things We Do For Love, The 10cc 5541 - 04 Cupid 112 5449 - 10 Dance With Me 112 5865 - 18 Peaches And Cream 112 5883 - 04 Right Here For You 112 6037 - 07 U Already Know 112 5790 - 02 Hot And Wet 112 & Ludacris 5689 - 04 Na Na Na 112 & Super Cat 5431 - 05 We Are One 12 Stones 5210 - 20 Chocolate 1975, The 6386 - 01 If You're Too Shy (Let Me Know) 1975, The 5771 - 18 Love Me 1975, The 6371 - 08 Me And You Together Song (Clean) 1975, The 6070 - 19 TOOTIMETOOTIMETOOTIME 1975, The 5678 - 02 I'm Different (Clean) 2 Chainz 5673 - 05 No Lie (Clean) 2 Chainz & Drake 5663 - 12 Birthday Song (Clean) 2 Chainz & Kanye West 5064 - 20 Feds Watching (Clean) 2 Chainz & Pharrell 5450 - 20 We Own It 2 Chainz & Wiz Khalifa 5293 - 09 I Do It (Clean) 2 Chainz Feat. -

Quirky Kids: a Pediatric Perspective on Evaluation of Children With

EileenEileen Costello,Costello, MDMD BostonBoston UniversityUniversity SchoolSchool ofof MedicineMedicine DepartmentDepartment ofof PediatricsPediatrics TheThe BrookingsBrookings InstitutionInstitution DecemberDecember 16,200516,2005 AutismAutism andand HopeHope WhyWhy Quirky?Quirky? • Affectionate • Not pejorative or a euphemism • Acceptable to many parents • Inclusive of the wide range of ASD kids • No prognostic significance • Accurate FeaturesFeatures sharedshared byby ASDASD kidskids • Developmental differences – Not always delays • Temperamental extremes • Sensory defensiveness • Social difficulties • Poorly developed Theory of Mind ConfusingConfusing DiagnosticDiagnostic TerminologyTerminology • Sensory Integration Dysfunction • Pervasive Developmental Delay- NOS • Pragmatic Language Disorder • “Autistic Spectrum Disorder” • Nonverbal Learning Disability • Right hemispheric Dysfunction • Asperger’s Syndrome • High Functioning Autism WhatWhat doesdoes thisthis meanmean forfor families?families? • Doesn’t follow “What to Expect” guidelines • Enormous stress of raising an atypically developing child • Language delays/differences>>frustration>>behavior problems • School difficulties • Social difficulties • Occupational difficulties • Longer term dependence on parents WhatWhat doesdoes thisthis meanmean forfor ourour communities?communities? • Increasing numbers of children with developmental disabilities • Huge implications for school districts – ASD children often need specialized services and educational setting – Expensive and labor -

Crucial Confrontations: Tools for Resolving Broken Promises

Crucial Confrontations: Tools for Resolving Broken Promises, Violated Expectations, and Bad Behavior by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan and Al Switzler ISBN:0071446524 McGraw-Hill © 2005 (284 pages) Use this book to learn how to step up to failed promises and deal with them in a way that both solves the problem and saves relationships. Table of Contents Crucial Confrontations—Tools for Resolving Broken Promises, Violated Expectations, and Bad Behavior Foreword Prefac - A Note to Our Readers e Introd - What’s a Crucial Confrontation? And Who Cares? uction Part One - Work on Me First—What to Do before a Crucial Confrontation Chapt - Choose What and If—How to Know What Crucial Confrontation to Hold and If You Should er 1 Hold It Chapt - Master My Stories—How to Get Your Head Right before Opening Your Mouth er 2 Part Two - Confront with Safety—What to Do during a Crucial Confrontation Chapt - Describe the Gap—How to Start a Crucial Confrontation er 3 Chapt - Make It Motivating—How to Help Others Want to Take Action er 4 Chapt - Make It Easy—How to Make Keeping Commitments (Almost) Painless er 5 Chapt - Stay Focused and Flexible—What to Do When Others Get Sidetracked, Scream, or Sulk er 6 Chapt - Agree on a Plan and Follow Up—How to Gain Commitment and Move to Action er 7 Part Three - Move to Action—What to Do after a Crucial Confrontation Chapt - Put It All Together—How to Solve Big, Sticky, Complicated Problems er 8 Chapt - The Twelve “Yeah-Buts”—How to Deal with the Truly Tough er 9 Appen - Where Do You Stand?—A Self-Assessment for Measuring Your Crucial Confrontation Skills dix A Appen - Six-Source Diagnostic Questions—The Six-Source Model dix B Appen - When Things Go Right dix C Appendix D Notes Index List of Sidebars Page 1 Back Cover Behind the problems that routinely plague families, teams, and organizations are individuals who either can’t or won’t deal with failed promises. -

Axis-Parents-Guide-To-Drake.Pdf

Drake “Drake is an interpreter, in other words, of the people he is trying to reach—an artist who can write lyrics that wide swaths of listeners will want to take ownership of and hooks that we will all want to sing to ourselves as we walk down the street. —Leon Neyfakh, “Peak Drake,” The FADER Does Drake have you in your feelings about how much your kids are listening to him? John Lennon famously said the Beatles were bigger than Jesus, but Aubrey Graham, aka Drake aka Drizzy, is now the best-selling solo male artist of all time. He has surpassed Elvis and Eminem, with over $218,000,000 in total record sales. Not only that, he was Billboard’s 2018 Top Artist and Spotify’s most-streamed artist, track, and album of 2018. Described by one writer as having “the Midas touch when it comes to making hits and singles,” it seems as though everything Drake does is successful. He appeals to those who like “harder” rap, but still excites a One Direction level of infatuation in young girls. Other rappers can take shots at his son and his parents [warning: strong language] without doing real damage to his career. He’s able to transform up-and-coming artists into superstars just by featuring them on his albums or being featured on theirs. With all of his influence on both his fans and the culture at large, it’s important to understand who Drake is, what he stands for, and what he’s teaching, both explicitly and implicitly, the people who listen to him. -

House Energy and Commerce Committee, Consumer Protection and Commerce Subcommittee Hearing on Protecting Consumer Privacy in The

Feb 27 2019 11:30:13 TRANSCRIPT February 26, 2019 COMMITTEE HEARING REP. JAN SCHAKOWSKY, D-ILL. WASHINGTON, DC HOUSE ENERGY AND COMMERCE COMMITTEE, CONSUMER PROTECTION AND COMMERCE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING ON PROTECTING CONSUMER PRIVACY IN THE ERA OF BIG DATA Bloomberg Government Support: 1-877-498-3587 www.bgov.com Copyright 2019. Provided under license from Bloomberg Government. All materials herein are protected by United States copyright law and/or license from Bloomberg Government, and may not be reproduced, distributed, transmitted, displayed, published or broadcast without the prior written permission of Bloomberg Government. You may not alter or remove any trademark, copyright or other notice from copies of the content. HOUSE ENERGY AND COMMERCE COMMITTEE, CONSUMER PROTECTION AND COMMERCE SUBCOMMITTEE HEARING ON PROTECTING CONSUMER PRIVACY IN THE ERA OF BIG DATA FEBRUARY 26, 2019 SPEAKERS: REP. JAN SCHAKOWSKY, D-ILL., CHAIR REP. TONY CARDENAS, D-CALIF. REP. BEN RAY LUJAN, D-N.M. REP. DEBBIE DINGELL, D-MICH. REP. DORIS MATSUI, D-CALIF. REP. LISA BLUNT ROCHESTER, D-DEL. REP. KATHY CASTOR, D-FLA. REP. ROBIN KELLY, D-ILL. REP. TOM O'HALLERAN, D-ARIZ. REP. JERRY MCNERNEY, D-CALIF. REP. BOBBY L. RUSH, D-ILL. REP. DARREN SOTO, D-FLA. REP. MARC VEASEY, D-TEXAS REP. FRANK PALLONE JR., D-N.J., EX OFFICIO REP. CATHY MCMORRIS RODGERS, R-WASH., RANKING MEMBER REP. BOB LATTA, R-OHIO REP. MICHAEL C. BURGESS, R-TEXAS REP. BRETT GUTHRIE, R-KY. REP. FRED UPTON, R-MICH. REP. LARRY BUCSHON, R-IND. REP. E.L. "BUDDY" CARTER, R-GA. REP. GREG GIANFORTE, R-MONT. -

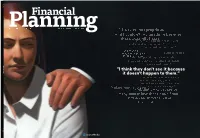

“I Think They Don't See It Because It Doesn't Happen to Them.”

May 2018 2018 May INVESTED IN ADVISORS/MAY 2018 FINANCIALPLANNING.COM / FINPLAN “It was so inappropriate, and I couldn’t say anything because these were “‘Everyone all clients.”is a member of the team and should be treated well.’ I’ve never heard that message.” “I’ve been told, “I was so scared.” ‘Wow, you’ve got your [lipstick] “I ended on today,’ up making an excuse that I needed to get coffee, and I ran back Financial Planning to my hotel room.” “I think they don’t see it because it doesn’t happen to them.” “I’m the only woman, and I walk in and this [client] says, ‘Wow, it’s nice to have an attractive woman here for a change.” “Culture starts at the top.” “I think that’s why you see so many women launch their own firms. They decide they’re tired of the bullshit.” Vol. 48/No.5 Vol. 002_FP0000_001 2 4/17/2018 10:47:05 AM 003_FP0000_001 3 4/17/2018 10:46:03 AM Contents May 2018 | VOL. 48 | NO. 5 34 10 Key 28 Findings Wealth Management Fares Worst on Sexual in Study of Sexual Harassment Harassment A survey covering From inappropriate touching to belittling comments, many industries shows woman advisors face workplace environments that troubling trends for are far from welcoming. wealth management. BY ANDREW WELSCH BY CHELSEA EMERY BONNIE McGEER nd DANA JACKSON Columns 12 A New Way to Live Instead of thinking about being a fiduciary purely as an obligation or regulation, advisors should envision it as a new lifestyle.