If You See Something, Say Something: a Look at Experimental Writing on Art

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Interiors and Interiority in Vermeer: Empiricism, Subjectivity, Modernism

ARTICLE Received 20 Feb 2017 | Accepted 11 May 2017 | Published 12 Jul 2017 DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 OPEN Interiors and interiority in Vermeer: empiricism, subjectivity, modernism Benjamin Binstock1 ABSTRACT Johannes Vermeer may well be the foremost painter of interiors and interiority in the history of art, yet we have not necessarily understood his achievement in either domain, or their relation within his complex development. This essay explains how Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and used his family members as models, combining empiricism and subjectivity. Vermeer was exceptionally self-conscious and sophisticated about his artistic task, which we are still laboring to understand and articulate. He eschewed anecdotal narratives and presented his models as models in “studio” settings, in paintings about paintings, or art about art, a form of modernism. In contrast to the prevailing con- ception in scholarship of Dutch Golden Age paintings as providing didactic or moralizing messages for their pre-modern audiences, we glimpse in Vermeer’s paintings an anticipation of our own modern understanding of art. This article is published as part of a collection on interiorities. 1 School of History and Social Sciences, Cooper Union, New York, NY, USA Correspondence: (e-mail: [email protected]) PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | 3:17068 | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 | www.palgrave-journals.com/palcomms 1 ARTICLE PALGRAVE COMMUNICATIONS | DOI: 10.1057/palcomms.2017.68 ‘All the beautifully furnished rooms, carefully designed within his complex development. This essay explains how interiors, everything so controlled; There wasn’t any room Vermeer based his interiors on rooms in his house and his for any real feelings between any of us’. -

SAINT PRAXEDIS by JOHANNES VERMEER - One of Only Two Paintings by the Artist in Private Hands

PRESS RELEASE | LONDON FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE: Monday, 9 June 2014 SAINT PRAXEDIS BY JOHANNES VERMEER - One of only two paintings by the artist in private hands - LEADS THE SALE OF WORKS FROM THE BARBARA PIASECKA JOHNSON COLLECTION WITH PROCEEDS TO BENEFIT THE BARBARA PIASECKA JOHNSON FOUNDATION AT CHRISTIE’S IN JULY London – Christie’s is pleased to announce that works from The Barbara Piasecka Johnson Collection with Proceeds to Benefit the Barbara Piasecka Johnson Foundation will be offered at Christie’s London from 8 to 17 July. The star lot is the famous painting of Saint Praxedis by Johannes Vermeer of Delft (1632-1675), from 1655, which is the earliest dated picture by the artist and one of only two from his rare oeuvre to remain in private hands (estimate: £6-8 million, illustrated above). The results of recent material technical analysis conducted by the Rijksmuseum in association with the Free University, Amsterdam endorses Vermeer’s authorship of the picture. They establish not only that the lead white used in the paint is consistent with Dutch painting and is incontrovertibly not Italian; they also reveal a precise match with another established early painting by Vermeer - Diana and her Companions, in The Mauritshuis, The Hague. The match even suggests that the exact same batch of paint was used for both paintings. This magnificent painting offers one of the rarest and most alluring opportunities for collectors and institutions this season. Please click here for the full catalogue note on this work. An art connoisseur whose dedicated collecting was underpinned by art historical training in Poland, where she was born, Barbara Piasecka Johnson (1937- 2013) was also a humanitarian and philanthropist. -

Beinecke Illuminated, No. 6, 2019–20 Annual Report

BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 6, 2019–20 Annual Report Front cover: Photograph of the scultpure garden by Iwan Baan. Back cover: Dr. Walter Evans, Melissa Barton, and Edwin C. Schroeder reviewing the Walter O. Evans Collection of Frederick Douglass and Douglass Family Papers. Contributors The Beinecke Rare Book & Manuscript Library acknowledges the following for their assistance in creating and compiling the content in this annual report. Articles written by, or adapted from, Michael Morand and Michael Cummings, with editorial assistance from David Baker, Bianca Ibarlucea, and Eva Knaggs. Statistics compiled by Ellen Doon, Moira Fitzgerald, Eric Friede, Michael Morand, Audrey Pearson, Allison Van Rhee, and the staff of Technical Services, Access Services, and Administration. Photographs of Beinecke Library events, exhibitions, and materials by Tubyez Cropper, Dante Haughton, and Michael Morand; Windham-Campbell Prize image from YaleNews; Georgia O’Keeffe manuscript images courtesy of Sotheby’s; Wayne Koestenbaum photo by Tim Schutsky; photograph of Matthew Dudley and Ozgen Felek by Michael Helfenbein. Design by Rebecca Martz, Office of the University Printer. Copyright ©2020 by Yale University facebook.com/beinecke @beineckelibrary twitter.com/BeineckeLibrary beinecke.library.yale.edu subsCribe to library news subscribe.yale.edu BEINECKE ILLUMINATED No. 6, 2019–20 Annual Report 4 From the Director 5 Exhibitions and Events Beyond Words: Experimental Poetry & the Avant-Garde Drafting Monique Wittig Subscribed: The Manuscript in Britain, 1500–1800 -

Thoughts About Paintings Conservation This Page Intentionally Left Blank Personal Viewpoints

PERSONAL VIEWPOINTS Thoughts about Paintings Conservation This page intentionally left blank Personal Viewpoints Thoughts about Paintings Conservation A Seminar Organized by the J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 EDITED BY Mark Leonard THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE LOS ANGELES & 2003 J- Paul Getty Trust THE GETTY CONSERVATION INSTITUTE Getty Publications 1200 Getty Center Drive, Suite 500 Timothy P. Whalen, Director Los Angeles, CA 90049-1682 Jeanne Marie Teutónico, Associate Director, www.getty.edu Field Projects and Science Christopher Hudson, Publisher The Getty Conservation Institute works interna- Mark Greenberg, Editor in Chief tionally to advance conservation and to enhance Tobi Levenberg Kaplan, Manuscript Editor and encourage the preservation and understanding Jeffrey Cohen, Designer of the visual arts in all of their dimensions— Elizabeth Chapín Kahn, Production Coordinator objects, collections, architecture, and sites. The Institute serves the conservation community through Typeset by G&S Typesetters, Inc., Austin, Texas scientific research; education and training; field Printed in Hong Kong by Imago projects; and the dissemination of the results of both its work and the work of others in the field. Library of Congress In all its endeavors, the Institute is committed Cataloging-in-Publication Data to addressing unanswered questions and promoting the highest possible standards of conservation Personal viewpoints : thoughts about paintings practice. conservation : a seminar organized by The J. Paul Getty Museum, the Getty Conservation Institute, and the Getty Research Institute at the Getty Center, Los Angeles, June 21-22, 2001 /volume editor, Mark Leonard, p. -

08 Tate Modern in the Studio

1 Antony Gormley (b. 1950), Untitled (for Francis), 1985 (Room 1), lead, plaster, polyester resin and fibreglass 1900 × 1170 × 290cm Giovanni Bellini, St Francis in Ecstasy, 1479-85 • Finding Meaning. In this room we have two apparently contrasting works. Over there an abstract work by Eva Hesse and here a human figure by Antony Gormley. They represent contrasting approaches that are explored in the following rooms. Gormley is best known for The Angel of the North (see Visual Aids) an enormous sculpture on a hill near Newcastle. • Construction. This work is called Untitled (for Francis) and was made in 1985. Like many of his other works it was made directly from his own body. He was wrapped in clingfilm by his wife, who is also an artist, and then covered in two layers of plaster. When it had dried the cast was cut from his body, reassembled and then covered in fibreglass and resin. Twenty-four sheets of lead were then hammered over the figure and soldered together. If you look closely you will see that the figure has been pierced in the breast, hands and feet by small holes cut in the lead. • St. Francis. The attitude of the eyeless figure, standing with head tilted back, feet apart and arms extended to display the palms of its hands, resembles that of a Christian saint receiving the stigmata. Stigmata are the five marks left on Christ’s 2 body by the Crucifixion although one of the wounds here is in the breast, rather than, as tradition dictates, in the side. -

A Rumba for Rothko and Other Poems Dennis O'connell Seton Hall University

Seton Hall University eRepository @ Seton Hall Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs) Spring 5-2015 A Rumba for Rothko and Other Poems Dennis O'Connell Seton Hall University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations Part of the Poetry Commons Recommended Citation O'Connell, Dennis, "A Rumba for Rothko and Other Poems" (2015). Seton Hall University Dissertations and Theses (ETDs). 2069. https://scholarship.shu.edu/dissertations/2069 A Rumba for Rothko and Other Poems by Dennis O’Connell M.A. Seton Hall University, 2015 A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Arts in Department of English Seton Hall University May 2015 2 © Dennis O’Connell All Rights Reserved 3 Approved by: _______________________________________ Mark Svenvold, Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Philip Schochet, Second Reader 4 Introduction Throughout the last few years, I have been examining the role that objects play within my poetic production. My hope was to notice my own interaction with objects more precisely and to pursue poetic questions (and philosophical implications about subjectivity and objectivity) that have been asked before by modernist writers such as Gertrude Stein and William Carlos Williams. These two writers in particular had their own reasons for pursuing, through their writing, basic questions about representation of the world in art and language. Stein’s program, modeled after her contemporaries Picasso and Braque, was to offer a fractal, or fragmented sort of representation of the world. Her cubist-inspired presentation in language of portraits of people, for instance, offered in language what the cubists were doing in the visual realm— “objects” of inquiry were shown from multiple perspectives, all at once. -

Travelling in a Palimpsest

MARIE-SOFIE LUNDSTRÖM Travelling in a Palimpsest FINNISH NINETEENTH-CENTURY PAINTERS’ ENCOUNTERS WITH SPANISH ART AND CULTURE TURKU 2007 Cover illustration: El Vito: Andalusian Dance, June 1881, drawing in pencil by Albert Edelfelt ISBN 978-952-12-1869-9 (digital version) ISBN 978-952-12-1868-2 (printed version) Painosalama Oy Turku 2007 Pre-print of a forthcoming publication with the same title, to be published by the Finnish Academy of Science and Letters, Humaniora, vol. 343, Helsinki 2007 ISBN 978-951-41-1010-8 CONTENTS PREFACE AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS. 5 INTRODUCTION . 11 Encountering Spanish Art and Culture: Nineteenth-Century Espagnolisme and Finland. 13 Methodological Issues . 14 On the Disposition . 17 Research Tools . 19 Theoretical Framework: Imagining, Experiencing ad Remembering Spain. 22 Painter-Tourists Staging Authenticity. 24 Memories of Experiences: The Souvenir. 28 Romanticism Against the Tide of Modernity. 31 Sources. 33 Review of the Research Literature. 37 1 THE LURE OF SPAIN. 43 1.1 “There is no such thing as the Pyrenees any more”. 47 1.1.1 Scholarly Sojourns and Romantic Travelling: Early Journeys to Spain. 48 1.1.2 Travelling in and from the Periphery: Finnish Voyagers . 55 2 “LES DIEUX ET LES DEMI-DIEUX DE LA PEINTURE” . 59 2.1 The Spell of Murillo: The Early Copies . 62 2.2 From Murillo to Velázquez: Tracing a Paradigm Shift in the 1860s . 73 3 ADOLF VON BECKER AND THE MANIÈRE ESPAGNOLE. 85 3.1 The Parisian Apprenticeship: Copied Spanishness . 96 3.2 Looking at WONDERS: Becker at the Prado. 102 3.3 Costumbrista Painting or Manière Espagnole? . -

“Just What Was It That Made U.S. Art So Different, So Appealing?”

“JUST WHAT WAS IT THAT MADE U.S. ART SO DIFFERENT, SO APPEALING?”: CASE STUDIES OF THE CRITICAL RECEPTION OF AMERICAN AVANT-GARDE PAINTING IN LONDON, 1950-1964 by FRANK G. SPICER III Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements For the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Dissertation Adviser: Dr. Ellen G. Landau Department of Art History and Art CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY May, 2009 CASE WESTERN RESERVE UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES We hereby approve the thesis/dissertation of Frank G. Spicer III ______________________________________________________ Doctor of Philosophy candidate for the ________________________________degree *. Dr. Ellen G. Landau (signed)_______________________________________________ (chair of the committee) ________________________________________________Dr. Anne Helmreich Dr. Henry Adams ________________________________________________ Dr. Kurt Koenigsberger ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ ________________________________________________ December 18, 2008 (date) _______________________ *We also certify that written approval has been obtained for any proprietary material contained therein. Table of Contents List of Figures 2 Acknowledgements 7 Abstract 12 Introduction 14 Chapter I. Historiography of Secondary Literature 23 II. The London Milieu 49 III. The Early Period: 1946/1950-55 73 IV. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 1, The Tate 94 V. The Middle Period: 1956-59: Part 2 127 VI. The Later Period: 1960-1962 171 VII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 1 213 VIII. The Later Period: 1963-64: Part 2 250 Concluding Remarks 286 Figures 299 Bibliography 384 1 List of Figures Fig. 1 Richard Hamilton Just What Is It That Makes Today’s Homes So Different, So Appealing? (1956) Fig. 2 Modern Art in the United States Catalogue Cover Fig. 3 The New American Painting Catalogue Cover Fig. -

An Affective Comparison of John Taggart and Mark Rothko

Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “You Do Feel Something, Right?” An Affective Comparison of John Taggart and Mark Rothko 2015 – 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Sarah Posman Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Michel Vandenbossche 2 3 4 5 Ghent University Faculty of Arts and Philosophy “You Do Feel Something, Right?” An Affective Comparison of John Taggart and Mark Rothko 2015 – 2016 Supervisor: Dr. Sarah Posman Paper submitted in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of “Master in Taal- en Letterkunde: Engels” by Michel Vandenbossche 6 7 Word of Thanks I would very much like to thank my parents, for their never-ending and unobtrusive support. Their love and faith keep pushing me towards ever greater things. Also, my best friends, who have sat through months of me bothering them with my troubles and writer’s blocks. They are the ones who have kept me going. And last but not least, my supervisor, Sarah Posman, for always being approachable, for replying quickly to all of my questions, and for being the rock on which this dissertation has been built. 8 Table of Contents 1 Introduction 10 2 Contextual Chapters 15 2.1 Affect Theory: A Terminology for the Arts 15 a) The Field of Affect Theory 15 b) Affect, Feeling and Emotion, Mood: Altieri 18 c) Affect and Modernist Abstraction: Sontag and Greenberg 21 d) Weak Affects: Sianne Ngai 23 2.2 Giving the Abstract a Look: Rothko and the Abstract Expressionists 25 a) Abstraction in the Visual Arts -

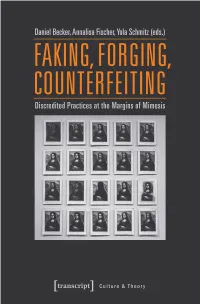

Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting

Daniel Becker, Annalisa Fischer, Yola Schmitz (eds.) Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting Daniel Becker, Annalisa Fischer, Yola Schmitz (eds.) in collaboration with Simone Niehoff and Florencia Sannders Faking, Forging, Counterfeiting Discredited Practices at the Margins of Mimesis Funded by the Elite Network of Bavaria as part of the International Doctoral Program MIMESIS. An electronic version of this book is freely available, thanks to the support of libraries working with Knowledge Unlatched. KU is a collaborative initiative designed to make high quality books Open Access for the public good. The Open Access ISBN for this book is 978-3-8394-3762-9. More information about the initiative and links to the Open Access version can be found at www.knowledgeunlatched.org. This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommer- cial-NoDerivs 4.0 (BY-NC-ND) which means that the text may be used for non- commercial purposes, provided credit is given to the author. For details go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/. To create an adaptation, translation, or derivative of the original work and for commercial use, further permission is required and can be obtained by contac- ting [email protected] © 2018 transcript Verlag, Bielefeld Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Na- tionalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the Internet at http://dnb.d-nb.de Cover concept: Maria Arndt, Bielefeld -

44 the Pharos/Winter 2016

Portrait of Hieronymus Bosch, 1570s. Cornelis Cort (1533–1578). Found in the collection of The Netherlands Institute for Art History, The Hague. Photo credit: HIP/Art Resource, NY. Pieter Bruegel the Elder. Painter and Patron (with Bruegel’s self portrait). Drawing. Pieter Bruegel the Elder (c. 1525–1569). Graphische Sammlung Albertina, Vienna, Austria. Photo credit: Erich Lessing/Art 44 Resource, NY. The Pharos/Winter 2016 Bosch and Bruegel Disability in sixteenth-century art Gregory W. Rutecki, MD The author (AΩA, University of Illinois, 1973) is a mem- depict ‘many things that cannot be depicted.’ ” 3p6 ber of the Department of General Internal Medicine at the In 1958, French physician Tony-Michel Torrillhon based Cleveland Clinic in Cleveland, Ohio. his doctoral thesis on the assertion that Bruegel’s accuracy in painting eye disease indicated that he was a physician,4 he Italian Renaissance reflected a best of all possible an inference that has never been proven. Torrilhon’s thesis worlds, an Elysian existence peopled by gods, angels, showed extensive examples of Bruegel’s uncanny anatomi- and men and women only a step below the angels.1 cal fidelity. That expertise also appears in both Bruegel’s and TThe Flemish school of art of the same period—ignored for Bosch’s depictions of other physical infirmities, illustrating the centuries—depicted less pleasant realities. Its paintings were artists’ sophisticated knowledge of anatomy.5 Further, their peopled by peasants and beggars. Originating in the Spanish work shows us in their details and settings how their subjects Netherlands, it was a culture soon to be embroiled in a bloody were treated in the sixteenth century. -

Inside the Camera Obscura – Optics and Art Under the Spell of the Projected Image

MAX-PLANCK-INSTITUT FÜR WISSENSCHAFTSGESCHICHTE Max Planck Institute for the History of Science 2007 PREPRINT 333 Wolfgang Lefèvre (ed.) Inside the Camera Obscura – Optics and Art under the Spell of the Projected Image TABLE OF CONTENTS PART I – INTRODUCING AN INSTRUMENT The Optical Camera Obscura I A Short Exposition Wolfgang Lefèvre 5 The Optical Camera Obscura II Images and Texts Collected and presented by Norma Wenczel 13 Projecting Nature in Early-Modern Europe Michael John Gorman 31 PART II – OPTICS Alhazen’s Optics in Europe: Some Notes on What It Said and What It Did Not Say Abdelhamid I. Sabra 53 Playing with Images in a Dark Room Kepler’s Ludi inside the Camera Obscura Sven Dupré 59 Images: Real and Virtual, Projected and Perceived, from Kepler to Dechales Alan E. Shapiro 75 “Res Aspectabilis Cujus Forma Luminis Beneficio per Foramen Transparet” – Simulachrum, Species, Forma, Imago: What was Transported by Light through the Pinhole? Isabelle Pantin 95 Clair & Distinct. Seventeenth-Century Conceptualizations of the Quality of Images Fokko Jan Dijksterhuis 105 PART III – LENSES AND MIRRORS The Optical Quality of Seventeenth-Century Lenses Giuseppe Molesini 117 The Camera Obscura and the Availibility of Seventeenth Century Optics – Some Notes and an Account of a Test Tiemen Cocquyt 129 Comments on 17th-Century Lenses and Projection Klaus Staubermann 141 PART IV – PAINTING The Camera Obscura as a Model of a New Concept of Mimesis in Seventeenth-Century Painting Carsten Wirth 149 Painting Technique in the Seventeenth Century in Holland and the Possible Use of the Camera Obscura by Vermeer Karin Groen 195 Neutron-Autoradiography of two Paintings by Jan Vermeer in the Gemäldegalerie Berlin Claudia Laurenze-Landsberg 211 Gerrit Dou and the Concave Mirror Philip Steadman 227 Imitation, Optics and Photography Some Gross Hypotheses Martin Kemp 243 List of Contributors 265 PART I INTRODUCING AN INSTRUMENT Figure 1: ‘Woman with a pearl necklace’ by Vermeer van Delft (c.1664).