Top of Page Interview Information--Different Title

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, California 94720

PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 94720 No. J4 February 1^80 In the beginning - wet who have beginnings, Bust think in ten end, Juet for thought's sake* - in the beginning was^plaeny failve, as it always does, and we have at once dead Matter, and Energy, or on aide by aids,—in aotive eunJunuLlmi fuieyei-r /"what we* -tic universe of Force and Matter is the dead itflalduyof previous 4 •Bftofa are In the. beginning 1 Matter and Fo4 CAUWPITCA m+Hti \ aautt, thayflntoraot forever^ and are inter-dependent, -fiti xm - ^A^dju^^LJ^ waturlallstie unlv»reO| always, ^. m Lawrence's Manuscript of Fantasia of the Unconscious During the summer of 1921 D. H. Law organized the seizure of 1,000 copies of The rence sat among the roots of trees at Eber- Rainbow on grounds of obscenity. Already steinberg at the edge of the Black Forest — notorious for his elopement with Frieda "between the toes of a tree, forgetting my Weekley-Richtofen, who at the age of self against the ankle of the trunk"—writing thirty-two was the wife of his Romance Fantasia of the Unconscious. He had come Languages professor and the mother of from Taormina to be with his wife who had three children, Lawrence was accused by the been there since early April, attending her critics of producing in this novel "an orgy sick mother. There is little mention of the of sexiness." He keenly felt the unfairness of book in Lawrence's correspondence, either this criticism and raged against the suppres then or later. -

“I Don't Care for My Other Books, Now”

THE LIBRARY University of California, Berkeley | No. 29 Fall 2013 | lib.berkeley.edu/give Fiat Lux “I don’t care for my other books, now” MARK TWAIN’S AUTOBIOGRAPHY CONTINUED by Benjamin Griffin, Mark Twain Project, Bancroft Library Mark Twain’s complete, uncensored Autobiography was an instant bestseller when the first volume was published in 2010, on the centennial of the author’s death, as he requested. The eagerly-awaited Volume 2 delves deeper into Twain’s life, uncovering the many roles he played in his private and public worlds. Affectionate and scathing by turns, his intractable curiosity and candor are everywhere on view. Like its predecessor, Volume 2 mingles a dia- ry-like record of Mark Twain’s daily thoughts and doings with fragmented and pungent portraits of his earlier life. And, as before, anything which Mark Twain had written but hadn’t, as of 1906–7, found a place to publish yet, might go in: Other autobiographies patiently and dutifully“ follow a planned and undivergent course through gardens and deserts and interesting cities and dreary solitudes, and when at last they reach their appointed goal they are pretty tired—and they The one-hundred-year edition comprises what have been frequently tired during the journey, too. could be called a director’s cut, says editor Ben But this is not that kind of autobiography. This one Griffin. “It hasn’t been cut to size or made to fit is only a pleasure excursion. the requirements of the market or brought into ” continued on page 6-7 line with notions of public decency. -

Smithing Service Now Leasing for Carton, Tax Included

Weather Inside MICHIGAN Sunny and warm today. Student Myths, p. 5- Ten High 62—66. nis Meet, p. 4. STATE UNIVERSITY P r ic e 10< East Lansing, Michigan Thurtdov, April 29, 1965 MSU Tops In Merit Scholars Again R e c o r d 2 1 7 Hannah Cites Agitators’ ‘Exploitation ’ T w i c e T o t a l University... studentsI are choice am fnr.-iûtetargets frtrfor ovnlftifexploitation it inn hvby * I’«I ’f*» king-brand’’ ideologists, President John A. Hannah told more than 50 business leaders who were on campus Wednesday to dedicate MSU’s new half-m illion dollar Packaging Building. A t H a r v a r d "Some persons like to use university campuses to advance op posing philosophies," he said. Kf By JIM STERBA He cited the ferment at Berkeley and smaller re\olts a: m any Administration Writer other universities as examples where protest techniques art the sa m e. For the third year in a row, "When you’ve been around for a loin’ time,’ he said, ’you re MSU has accepted more Merit cognize the same techniques being us I over V Scholars than any other univer "The basic objective is to sity, the National M erit Scholar create doubt against all con ship Corp. announced Wednes stituted authority," he said. day. The direction comes from a C h a r g e s Out of over 1,900 students few core agitators, he said, "but named M erit Scholars, 214 have these few are not effective un chosen to attend MSU next fall. -

Commartslectures00connrich.Pdf

of University California Berkeley Regional Oral History Office University of California The Bancroft Library Berkeley, California University History Series Betty Connors THE COMMITTEE FOR ARTS AND LECTURES, 1945-1980: THE CONNORS YEARS With an Introduction by Ruth Felt Interviews Conducted by Marilynn Rowland in 1998 Copyright 2000 by The Regents of the University of California Since 1954 the Regional Oral History Office has been interviewing leading participants in or well-placed witnesses to major events in the development of northern California, the West, and the nation. Oral history is a method of collecting historical information through tape-recorded interviews between a narrator with firsthand knowledge of historically significant events and a well- informed interviewer, with the goal of preserving substantive additions to the historical record. The tape recording is transcribed, lightly edited for continuity and clarity, and reviewed by the interviewee. The corrected manuscript is indexed, bound with photographs and illustrative materials, and placed in The Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley, and in other research collections for scholarly use. Because it is primary material, oral history is not intended to present the final, verified, or complete narrative of events. It is a spoken account, offered by the interviewee in response to questioning, and as such it is reflective, partisan, deeply involved, and irreplaceable. ************************************ All uses of this manuscript are covered by a legal agreement between The Regents of the University of California and Betty Connors dated January 28, 2001. The manuscript is thereby made available for research purposes. All literary rights in the manuscript, including the right to publish, are reserved to The Bancroft Library of the University of California, Berkeley. -

To the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005)

Index to the Baum Bugle Supplement for Volumes 46-49 (2002-2005) Adams, Ryan Author "Return to The Marvelous Land of Oz Producer In Search of Dorothy (review): One Hundred Years Later": "Answering Bell" (Music Video): 2005:49:1:32-33 2004:48:3:26-36 2002:46:1:3 Apocrypha Baum, Dr. Henry "Harry" Clay (brother Adventures in Oz (2006) (see Oz apocrypha): 2003:47:1:8-21 of LFB) Collection of Shanower's five graphic Apollo Victoria Theater Photograph: 2002:46:1:6 Oz novels.: 2005:49:2:5 Production of Wicked (September Baum, Lyman Frank Albanian Editions of Oz Books (see 2006): 2005:49:3:4 Astrological chart: 2002:46:2:15 Foreign Editions of Oz Books) "Are You a Good Ruler or a Bad Author Albright, Jane Ruler?": 2004:48:1:24-28 Aunt Jane's Nieces (IWOC Edition "Three Faces of Oz: Interviews" Arlen, Harold 2003) (review): 2003:47:3:27-30 (Robert Sabuda, "Prince of Pop- National Public Radio centennial Carodej Ze Zeme Oz (The ups"): 2002:46:1:18-24 program. Wonderful Wizard of Oz - Czech) Tribute to Fred M. Meyer: "Come Rain or Come Shine" (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 2004:48:3:16 Musical Celebration of Harold Carodejna Zeme Oz (The All Things Oz: 2002:46:2:4 Arlen: 2005:49:1:5 Marvelous Land of Oz - Czech) All Things Oz: The Wonder, Wit, and Arne Nixon Center for Study of (review): 2005:49:2:32-33 Wisdom of The Wizard of Oz Children's Literature (Fresno, CA): Charobnak Iz Oza (The Wizard of (review): 2004:48:1:29-30 2002:46:3:3 Oz - Serbian) (review): Allen, Zachary Ashanti 2005:49:2:33 Convention Report: Chesterton Actress The Complete Life and -

Documenting the Biotechnology Industry in the San Francisco Bay Area

Documenting the Biotechnology Industry In the San Francisco Bay Area Robin L. Chandler Head, Archives and Special Collections UCSF Library and Center for Knowledge Management 1997 1 Table of Contents Project Goals……………………………………………………………………….p. 3 Participants Interviewed………………………………………………………….p. 4 I. Documenting Biotechnology in the San Francisco Bay Area……………..p. 5 The Emergence of An Industry Developments at the University of California since the mid-1970s Developments in Biotech Companies since mid-1970s Collaborations between Universities and Biotech Companies University Training Programs Preparing Students for Careers in the Biotechnology Industry II. Appraisal Guidelines for Records Generated by Scientists in the University and the Biotechnology Industry………………………. p. 33 Why Preserve the Records of Biotechnology? Research Records to Preserve Records Management at the University of California Records Keeping at Biotech Companies III. Collecting and Preserving Records in Biotechnology…………………….p. 48 Potential Users of Biotechnology Archives Approaches to Documenting the Field of Biotechnology Project Recommendations 2 Project Goals The University of California, San Francisco (UCSF) Library & Center for Knowledge Management and the Bancroft Library at the University of California, Berkeley (UCB) are collaborating in a year-long project beginning in December 1996 to document the impact of biotechnology in the Bay Area. The collaborative effort is focused upon the development of an archival collecting model for the field of biotechnology to acquire original papers, manuscripts and records from selected individuals, organizations and corporations as well as coordinating with the effort to capture oral history interviews with many biotechnology pioneers. This project combines the strengths of the existing UCSF Biotechnology Archives and the UCB Program in the History of the Biological Sciences and Biotechnology and will contribute to an overall picture of the growth and impact of biotechnology in the Bay Area. -

Report of the Commission on the Future of the UC Berkeley Library

Report of the Commission on the Future of the UC Berkeley Library October 2013 Acknowledgements The Commission would like to thank those who graciously contributed their time, expertise, and insight toward making this report complete. We are especially grateful to the experts who participated in our March 1 symposium, “The University Library in the 21st Century:” • Robert Darnton, Director of the Harvard University Library. • Peter Jerram, Chief Executive Officer, PLoS. • Tom Leonard, University Librarian. • Peter Norvig, Director of Research, Google. • Pamela Samuelson, Richard M. Sherman Distinguished Professor of Law and Information; Co-Director, Berkeley Center for Law & Technology. • Kevin Starr, California State Librarian Emeritus. We would also like to thank the UC Berkeley administrators who spent a great deal of time answering questions from the Commission, particularly Tom Leonard, University Librarian; Beth Dupuis, Associate University Librarian; Bernie Hurley, Associate University Librarian; Elise Woods, Library CFO; Erin Gore, Associate Vice Chancellor and Campus CFO; and Laurent Heller, Budget Director. From the California Digital Library, Executive Director Laine Farley and Director of Collection Development Ivy Anderson generously spent time with the Commission to explain the economics of licensing resources for the University of California system. We are grateful to the Graduate Assembly, the ASUC, the participants in Spring 2013 DeCal course “Student Commission on the Future of the Library,” and especially Natalie Gavello for their sustained and thoughtful communications with us throughout this process regarding the students’ perspectives on the Library. Other groups that lent their time and expertise toward shaping this report include the Academic Senate Library Committee, the Executive Committee of the Librarians’ Association of the University of California – Berkeley, and the Library Advisory Board. -

The Anchor, Volume 61.10: February 24, 1949

Hope College Hope College Digital Commons The Anchor: 1949 The Anchor: 1940-1949 2-24-1949 The Anchor, Volume 61.10: February 24, 1949 Hope College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1949 Part of the Library and Information Science Commons Recommended Citation Repository citation: Hope College, "The Anchor, Volume 61.10: February 24, 1949" (1949). The Anchor: 1949. Paper 3. https://digitalcommons.hope.edu/anchor_1949/3 Published in: The Anchor, Volume 61, Issue 10, February 24, 1949. Copyright © 1949 Hope College, Holland, Michigan. This News Article is brought to you for free and open access by the The Anchor: 1940-1949 at Hope College Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Anchor: 1949 by an authorized administrator of Hope College Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. •V Hope College Anchor ua—10 Official Publication of the Students of Hope College at Holland, Michigan February 24, 1949 All Girl Event Will Include Men's Glee Club Delineates Spring Ceitume, Slumber Parties Probably the biggest all-girl Vacation Tour Covering Four States event on the campus during the year is the annual WAL party. Photo Club Plans Club Will Make This February 25 it will be in the form of a masquerade and slum- Snapshot Tryst Trip Out East ber party. Under the co-chairman- A snapshot contest was put in ship of Ruth DeGraaf and Phyllis form at the last meeting of the During Vacation Sherman the party promises to be shutter bugs. It is open to all col- one that none of the girls will The Hope College Men's Glee lege students regardless of his or want to miss. -

Campus Parking Map

Campus Parking Map 1 2 3 4 5 University of Mediterranean California Botanical Garden of PARKING DESIGNATION Human Garden Asian Old Roses Bicycle Dismount Zone Genome Southern Australasian South 84 Laboratory Julia African American (M-F 8am-6pm) Morgan New World Central Campus permit Rd Hall C vin Desert al 74 C Herb Campus building 86 83 Garden F Faculty/staff permit Cycad & Chinese Palm Medicinal Garden Herb Construction area 85 Garden S Student permit Miocene Eastern Mexican/ 85B Central Forest North P Botanical American American a Visitor Information n Disabled (DP) parking Strawberry Garden o Botanical r Entrance Lot Mather Californian a Redwood Garden m Entrance ic Grove Emergency Phone P Public Parking (fee required)** A l l P A i a SSL F P H V a c r No coins needed - Dial 9-911 or 911e Lower T F H e Lot L r Gaus e i M Motorcycle permit s W F a Mathematical r Molecular e y SSL H ial D R n Campus parking lot Sciences nn Foundry d a Upper te National 73 d en r Research C o RH Lot Center for J Residence Hall permit Institute r Electron Lo ire Tra e Permit parking street F i w n l p Microscopy er 66 Jorda p 67 U R Restricted 72 3 Garage entrance 62 MSRI P H Hill Area permit Parking 3 Garage level designation Only Grizzly 3 77A rrace Peak CP Carpool parking permit (reserved until 10 am) Te Entrance Coffer V Dam One way street C 31 y H F 2 Hill 77 Lot a P ce W rra Terrace CS Te c CarShare Parking 69 i Streetm Barrier V e 1 a P rrac Lots r Te o n a V Visitor Parking on-campus P V Lawrence P East Bicycle Parking - Central Campus Lot 75A -

B a N C R O F T I a N a Published Occasionally by the Friends of the Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley, Califo

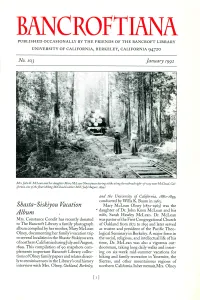

BANCROFTIANA PUBLISHED OCCASIONALLY BY THE FRIENDS OF THE BANCROFT LIBRARY UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA, BERKELEY, CALIFORNIA 9472O No. IOJ January 1992 Mrs. John K. McLean and her daughter Mary McLean Olney pause during a hike along the railroad right-of-way nearMcCloud, Cal ifornia, site of the flourishing McCloud Lumber Mill (July/August, 1899). and the University of California, 1880-18%, conducted by Willa K. Baum in 1963. Shasta-Siskiyou Vacation Mary McLean Olney (1872-1965) was the daughter of Dr. John Knox McLean and his Album wife, Sarah Hawley McLean. Dr. McLean Mrs. Constance Condit has recently donated was pastor of the First Congregational Church to The Bancroft Library a family photograph of Oakland from 1872 to 1895 an<^ later served album compiled by her mother, Mary McLean as trustee and president of the Pacific Theo Olney, documenting her family's vacation trip logical Seminary in Berkeley. A major force in to several localities in the Shasta-Siskiyou area the social, religious, and intellectual life of his of northern California during July and August, time, Dr. McLean was also a vigorous out- 1899. This compilation of 90 snapshots com doorsman, taking long daily walks and insist plements important Bancroft Library collec ing on six-week mid-summer vacations for tions of Olney family papers and relates direct hiking and family recreation in Yosemite, the ly to reminiscences in the Library's oral history Sierras, and other mountainous regions of interview with Mrs. Olney, Oakland, Berkeley,norther n California. In her memoir, Mrs. Olney [1] describes the Yosemite jaunts and also several historian Ernst Kantorowicz who "brought childhood trips to the Mount Shasta area me to a new vision of the creative spirit and the of Jess's collages will be on display for the first and business associates. -

Fine Books in All Fields the Winky King Collection of Oz & L. Frank

Sale 426 Thursday, April 15, 2010 1:00 PM Fine Books in All Fields The Winky King Collection of Oz & L. Frank Baum Illustrated & Children’s Books – Fine Press Books Auction Preview Tuesday, April 13 - 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM Wednesday, April 14 - 9:00 AM to 5:00 PM Thursday, April 15 - 9:00 AM to 11:00 AM Or by appointment 133 Kearny Street 4th Floor:San Francisco, CA 94108 phone: 415.989.2665 toll free: 1.866.999.7224 fax: 415.989.1664 [email protected]:www.pbagalleries.com REAL-TIME BIDDINGAVAILABLE PBA Galleries features Real-Time Bidding for its live auctions. This feature allows Internet Users to bid on items instantaneously, as though they were in the room with the auctioneer. If it is an auction day, you may view the Real-Time Bidder at http://www.pbagalleries.com/realtimebidder/ . Instructions for its use can be found by following the link at the top of the Real-Time Bidder page. Please note: you will need to be logged in and have a credit card registered with PBA Galleries to access the Real-Time Bidder area. In addition, we continue to provide provisions for Absentee Bidding by email, fax, regular mail, and telephone prior to the auction, as well as live phone bidding during the auction. Please contact PBA Galleries for more information. IMAGES AT WWW.PBAGALLERIES.COM All the items in this catalogue are pictured in the online version of the catalogue at www.pbagalleries. com. Go to Live Auctions, click Browse Catalogues, then click on the link to the Sale. -

Julia Morgan Records at the University of California Berkeley, 1893-1988 (Bulk 1901-1940)

http://oac.cdlib.org/findaid/ark:/13030/tf7r29p0df Online items available Inventory of the Julia Morgan Records at the University of California Berkeley, 1893-1988 (bulk 1901-1940) Collections processed by Elizabeth Konzak; finding aid created by Heather Briston; machine-readable finding aid derived from MS-Word, MS-Access and MS-Excel by Michael C. Conkin © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. 1 Inventory of the Julia Morgan Records at the University of California Berkeley, 1893-1988 (bulk 1901-1940) Environmental Design Archives University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California Encoded by: Michael Conkin © 2001 The Regents of the University of California. All rights reserved. Descriptive Summary Title: Julia Morgan Records at the University of California Berkeley, Date (inclusive): 1893-1988 (bulk 1901-1940) Creator: Morgan, Julia, 1872-1957 Extent: 6.5 boxes, 1 flat box, 13 flat file drawers, 34 tubes, 1 oversize volume, 1 portfolio, l model (77 linear feet) Repositories: Environmental Design Archives University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720-1820 The Bancroft Library University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720-6000 The Bancroft Library, University Archives University of California, Berkeley Berkeley, California 94720-6000 Language: English. Provenance The Julia Morgan materials at the University of California, Berkeley were donated to the respective repositories over time, by several different donors. The Environmental Design Archives received its initial donation of materials in 1959 with subsequent donations by different donors between the years 1969-1989. The Julia Morgan/Forney Collection was donated in 1983. The Julia Morgan materials held in The Bancroft Library were donated by several donors over a period of time spanning from 1971-1990.