Henry Duncan and the Savings Bank Movement in the UK

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Business Banking Service Quality - Great Britain

Business banking service quality - Great Britain Independent service quality survey results Business current accounts Published August 2019 As part of a regulatory requirement, an independent survey was conducted to ask customers of the 14 largest business current account providers if they would recommend their provider to other small and medium-sized enterprises (SMEs*). The results represent the view of customers who took part in the survey. These results are from an independent survey carried out between July 2018 and June 2019 by BVA BDRC as part of a regulatory requirement, and we have published this information at the request of the providers and the Competition and Markets Authority so you can compare the quality of service from business current account providers. In providing this information, we are not giving you any advice or making any recommendation to you. SME customers with business current accounts were asked how likely they would be to recommend their provider, their provider’s online and mobile banking services, services in branches and business centres, SME overdraft and loan services and relationship/account management services to other SMEs. The results show the proportion of customers of each provider who said they were ’extremely likely’ or ‘very likely’ to recommend each service. Participating providers: Allied Irish Bank (GB), Bank of Scotland, Barclays, Clydesdale Bank, Handelsbanken, HSBC UK, Lloyds Bank, Metro Bank, NatWest, Royal Bank of Scotland, Santander UK, The Co-operative Bank, TSB, Yorkshire Bank. Approximately 1,200 customers a year are surveyed across Great Britain for each provider; results are only published where at least 100 customers have provided an eligible score for that service in the survey period. -

David Duncan and His Descendants

THE STORY OF THOMAS DUNCAN AND HIS SIX SONS BY KATHERINE DUNCAN SMITH (Mrs. J. Morgan Smith) NEW YORK TOBIAS A. WRIGHT, INc. PRINTERS AND PUBLISHERS 1928 FOREWORD ESEARCH in Duucan genealogy was begun in 1894 and has been R carried on industriously to this date through Court records, VVills, Deeds, Bible records and tombstone inscriptions which have furnished proof and have affixed the seal of authenticity to much of the recorded data. Interested kinspeople have contributed from their store of family traditions some of which have been found to agree with certain facts and may be considered true. Many letters have been received, principally from descendants of Daniel and Stephen Duncan, extracts of which appear in this history and are mute evidence of the interest the writers feel in their lineage and their desire to worthily live and teach their chil dren to hold to the standard set by their ancestors. That there are errors in this publication there can be no doubt, but not of my making for: "I cannot tell how the truth may be; I say the tale as 'twas said to me." (Sir Walter Scott.) The frequent appearance of my name and the very personal nature of this book is warranted, somewhat, by the fact that all along the thought has been it would be distributed, mainly, among the descendants of Daniel and Stephen Duncan, between whose families there is very close relationship because of the intermar riage of many cousins. The stretch of years between 1894 and 1928 is a long one and it is not possible for me to estimate the time I have given to my self-imposed task, but if this book shall meet with favor and be prized by those into whose hands it may fall, the hours, days and weeks devoted to The Story of Thom,,as Dun can and His Si.r Sons will be remembered by me as pastime. -

Lloyds Banking Group Plc 25 Gresham Street by Electronic Submission London EC2V 7HN United Kingdom +44 (0) 208 936 5738 Direct [email protected]

Public Affairs Jonathan Gray Regulatory Developments Director February 13th, 2012 Lloyds Banking Group plc 25 Gresham Street By electronic submission London EC2V 7HN United Kingdom +44 (0) 208 936 5738 direct [email protected] Office of the Comptroller of Currency Securities and Exchange Commission 250 E Street, S.W., Mail Stop 2-3 100 F Street, N.E. Washington, D.C. 20219 Washington, D.C. 20549-1090 Docket ID OCC-2011-14 File Number S7-41-11 Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Commodity Futures Trading Commission System Three Lafayette Centre 20th Street and Constitution Avenue, N.W. 1155 21st Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20551 Washington, D.C. 20581 Docket No. R-1432 & RIN 7100 AD82 Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation 550 17th Street, N.W. Washington, D.C. 20429 RIN 3064-AD85 Re: Restrictions on Proprietary Trading and Certain Interests In, and Relationships With, Hedge Funds and Private Equity Funds Dear Ladies and Gentlemen: Lloyds Banking Group is pleased to provide comments on the joint notices of proposed rulemaking to implement Section 619 of the Dodd-Frank Wall Street Reform and Consumer Protection Act, more commonly known as the 'Volcker Rule'. Lloyds Banking Group ('the Group') is a UK headquartered retail and commercial bank. The Group has over 30 million customers and is the UK's leading provider of current accounts, savings, personal loans, credit cards and mortgages. Whilst we undertake the majority of our business in the UK, we also operate in a number of other countries including the United States of America. The Group fully endorses the detailed submissions on the proposed rules which have been made by the International Institute of Bankers (IIB). -

Co-Operatives, Friendly Societies and Trusts

This chapter was originally Chapter 28 in the second edition of Equity & Trusts, which was published in 2001. My intention in writing this essay as part of a textbook on trusts law was to include within the trusts law canon elements of the law of unincorporated associations (otherwise a staple of trusts law courses in relation to certainty of objects) relating to co- operative societies and friendly societies which are separately regulated and which arise (now) under separate legislative codes. Part of the interest, for me, in considering these topics was to expand the basis on which property law is commonly understood to arise. So, in relation to co-operatives for example, it is evident that property can be owned by a group of people without any individual within that group having separate, severable rights. Akin to the concepts of joint tenancy, survivorship and unity of interest in land law, it is possible for someone to be a co-owner of property but to own nothing one’s self individually. If you like, this is the perfect communist model of property: together we own everything, separately we own nothing. CO-OPERATIVES, FRIENDLY SOCIETIES AND TRUSTS 28.1 INTRODUCTION 28.1.1 The overlap between co-operatives and trusts At the time of writing, no other book on equity and trusts considers co-operatives and friendly societies as part of the general discussion of the better-established topics: although all of those books do consider unincorporated associations and their interaction with express trusts.1 Co-operatives and friendly societies have traditionally been forms of unincorporated associations. -

The Royal Bank of Scotland Group Pie File No

UNITED STATES SECURITI ES AND EXCHANGE COMMISSION WASHINGTON, DC 20549 DIVISION OF TRADING AND MARKETS August 3, 20 15 Ms. Connie Milonakis Davis Polk & Wardwell London LLP 5 Aldermanbury Square London EC2V 7HR England Re: The Royal Bank of Scotland Group pie File No. TP 15-17 Dear Ms. Milonakis: In your letter dated August 3, 2015, as supplemented by conversations with the staff, you request on behalf ofThe Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc, a public limited company organized under the laws of the United Kingdom and registered in Scotland ("RBSG"), an exemption from Rule 102 of Regulation Munder the Securities Exchange Act of 1934, as amended ("Exchange Act") in connection with the distribution of the ordinary shares of RBSG ("RBSG Shares") and the American Depositary Shares each representing the right to receive two RBSG Shares ("RBSG ADSs") by way of a placement of RBSG Shares (the "Placing") to interested purchasers by United Kingdom Financial Investments, which manages the shareholding of the United Kingdom Treasury in RBSG. 1 You seek an exemption to permit RBSG and RBSG Affiliates to conduct specified transactions outside the United States in RBSG Ordinary Shares during the Placing. Specifically, you request that: (i) RBSG CIB be permitted to continue to engage in derivatives and investor product market-making and hedging activities as described in your letter; (ii) the RBSG Asset Manager and RBSG Investment Managers be permitted to continue to engage in investment management activities as described in your letter; (iii) the RBSG Trustees and Personal Representatives be permitted to continue to engage in trustee and personal representative-related activities as described in your letter; (iv) the RBSG Banking Units be permitted to continue to engage in banking-related activities as described in your letter; and (v) the RBSG Stock Borrowing and Lending Units be permitted to continue to engage in stock borrowing and lending activities as described in your letter. -

Bank of Scotland

Bank of Scotland plc (Incorporated with limited liability in Scotland with registered number SC 327000) €60 billion Covered Bond Programme unconditionally guaranteed by HBOS plc (incorporated with limited liability in Scotland with registered number SC218813) and unconditionally and irrevocably guaranteed as to payments of interest and principal by HBOS Covered Bonds LLP (a limited liability partnership incorporated in England and Wales) Under this €60 billion covered bond programme (the “Programme”), Bank of Scotland plc (the “Issuer”) may from time to time issue bonds (the “Covered Bonds”) denominated in any currency agreed between the Issuer and the relevant Dealer(s) (as defined below). The payments of all amounts due in respect of the Covered Bonds have been unconditionally guaranteed by HBOS plc (“HBOS” in its capacity as guarantor, the “HBOS Group Guarantor”). HBOS Covered Bonds LLP (the “LLP” and, together with the HBOS Group Guarantor, the “Guarantors”) has guaranteed payments of interest and principal under the Covered Bonds pursuant to a guarantee which is secured over the Portfolio (as defined below) and its other assets. Recourse against the LLP under its guarantee is limited to the Portfolio and such assets. The Covered Bonds may be issued in bearer or registered form (respectively “Bearer Covered Bonds” and “Registered Covered Bonds”). The maximum aggregate nominal amount of all Covered Bonds from time to time outstanding under the Programme will not exceed €60 billion (or its equivalent in other currencies calculated as described in the Programme Agreement described herein), subject to increase as described herein. The Covered Bonds may be issued on a continuing basis to one or more of the Dealers specified under General Description of the Programme and any additional Dealer appointed under the Programme from time to time by the Issuer (each a “Dealer” and together the “Dealers”), which appointment may be for a specific issue or on an ongoing basis. -

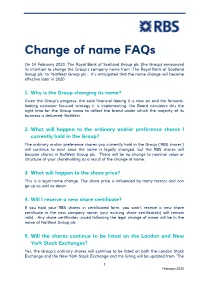

Change of Name Faqs

Change of name FAQs On 14 February 2020, The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc (the Group) announced its intention to change the Group’s company name from ‘The Royal Bank of Scotland Group plc’ to ‘NatWest Group plc’. It’s anticipated that the name change will become effective later in 2020. 1. Why is the Group changing its name? Given the Group’s progress, the solid financial footing it is now on and the forward- looking customer focused strategy it is implementing, the Board considers this the right time for the Group name to reflect the brand under which the majority of its business is delivered: NatWest. 2. What will happen to the ordinary and/or preference shares I currently hold in the Group? The ordinary and/or preference shares you currently hold in the Group (‘RBS shares’) will continue to exist once the name is legally changed, but the RBS shares will become shares in NatWest Group plc. There will be no change to nominal value or structure of your shareholding as a result of the change of name. 3. What will happen to the share price? This is a legal name change. The share price is influenced by many factors and can go up as well as down. 4. Will I receive a new share certificate? If you hold your RBS shares in certificated form, you won’t receive a new share certificate in the new company name; your existing share certificate(s) will remain valid. Any share certificates issued following the legal change of name will be in the name of NatWest Group plc. -

Bank of England List of Banks- October 2020

LIST OF BANKS AS COMPILED BY THE BANK OF ENGLAND AS AT 1st October 2020 (Amendments to the List of Banks since 31st August 2020 can be found below) Banks incorporated in the United Kingdom ABC International Bank Plc DB UK Bank Limited Access Bank UK Limited, The Distribution Finance Capital Limited Ahli United Bank (UK) PLC AIB Group (UK) Plc EFG Private Bank Limited Al Rayan Bank PLC Europe Arab Bank plc Aldermore Bank Plc Alliance Trust Savings Limited (Applied to Cancel) FBN Bank (UK) Ltd Allica Bank Ltd FCE Bank Plc Alpha Bank London Limited FCMB Bank (UK) Limited Arbuthnot Latham & Co Limited Atom Bank PLC Gatehouse Bank Plc Axis Bank UK Limited Ghana International Bank Plc GH Bank Limited Bank and Clients PLC Goldman Sachs International Bank Bank Leumi (UK) plc Guaranty Trust Bank (UK) Limited Bank Mandiri (Europe) Limited Gulf International Bank (UK) Limited Bank Of Baroda (UK) Limited Bank of Beirut (UK) Ltd Habib Bank Zurich Plc Bank of Ceylon (UK) Ltd Hampden & Co Plc Bank of China (UK) Ltd Hampshire Trust Bank Plc Bank of Ireland (UK) Plc Handelsbanken PLC Bank of London and The Middle East plc Havin Bank Ltd Bank of New York Mellon (International) Limited, The HBL Bank UK Limited Bank of Scotland plc HSBC Bank Plc Bank of the Philippine Islands (Europe) PLC HSBC Private Bank (UK) Limited Bank Saderat Plc HSBC Trust Company (UK) Ltd Bank Sepah International Plc HSBC UK Bank Plc Barclays Bank Plc Barclays Bank UK PLC ICBC (London) plc BFC Bank Limited ICBC Standard Bank Plc Bira Bank Limited ICICI Bank UK Plc BMCE Bank International plc Investec Bank PLC British Arab Commercial Bank Plc Itau BBA International PLC Brown Shipley & Co Limited JN Bank UK Ltd C Hoare & Co J.P. -

Natwest Group United Kingdom

NatWest Group United Kingdom Active This profile is actively maintained Send feedback on this profile Created before Nov 2016 Last update: Feb 23 2021 About NatWest Group NatWest Group, founded in 1727, is a British banking and insurance holding company based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Its main subsidiary companies are The Royal Bank of Scotland, NatWest, Ulster Bank and Coutts. Prior to a name-change in July 2020, it was known as Royal Bank of Scotland (RBS) Group. After a massive bailout in 2008, a majority of RBS' shares were purchased by the UK Government. In 2014 the bank embarked on a restructuring process that saw it refocus on its business in the UK and Ireland. As part of this process it divested its ownership of Citizens Financial Group, the 13th largest bank in the United States, in 2015. As of 2020 it remains 61.93% UK Government owned, via UK Financial Investments (UKFI). Website https://www.natwestgroup.com/ Headquarters 36 St Andrew Square EH2 2YB Edinburgh Scotland United Kingdom CEO/chair Alison Rose CEO Supervisor Bank of England Annual report Annual report 2020 Ownership listed on London Stock Exchange Natwest Group is majority-owned by the UK government since 2008, which currently holds 61.93 % of the shares. Complaints NatWest Group does not operate a complaints channel for individuals and communities that may be adversely affected by and its finance. However, the bank can be contacted via the contact form here (e.g. using ‘General Service’ as account type). grievances Stakeholders may raise complaints via the OECD National Contact Points (see OECD Watch guidance). -

REGISTRAR of FRIENDLY SOCIETIES We Are the FSB Contents 51St Annual Report of the Registrar of Friendly Societies for the 2013 CALENDAR YEAR Financial Services Board

20 ANNUAL 13 REPORT REGISTRAR OF FRIENDLY SOCIETIES we are the FSB Contents 51st Annual Report of the Registrar of Friendly Societies FOR THE 2013 CALENDAR YEAR Financial Services Board Table Page Vision, Mission and Values ................................................................................................................................ - 01 Executive Officer’s Report .................................................................................................................................. - 04 Report by the Registrar of Friendly Societies to the Minister of Finance ..................................................... - 05 Revenue and expenditure of self-administered friendly societies ................................................................. 1 09 Assets and liabilities of self-administered friendly societies ........................................................................... 2 10 Investment composition of self-administered friendly societies ................................................................... 3 11 Five-year overview of number of registered friendly societies ....................................................................... 4 12 Number of societies that submitted returns ..................................................................................................... 5 12 Number of members in societies ....................................................................................................................... 6 12 Benefits paid – all societies ................................................................................................................................ -

Henry Duncan Awards

Henry Duncan Awards - December 2016 Organisation Name Board Amount Approved Ayrshire, East (2 records) £10,000.00 Ayr: Newton Wallacetown Church of Scotland towards the salary of the full-time Youth & £5,000.00 Community Worke. Break the Silence towards rental costs of the centrally located £5,000.00 premises Clackmannanshire (1 record) £4,500.00 Play Alloa towards delivery of the weekly Adult Social £4,500.00 Group. Dumfries & Galloway (1 record) £4,000.00 Independent Living Support towards salary costs of the part-time Youth £4,000.00 Worker to maintain and develop the West of Dumfries and Galloway to provide support to young people who are homeless or at risk of becoming homeless Dundee City (3 records) £12,000.00 Dundee Crisis Pregnancy Trust towards the costs of the youth work programmes £4,000.00 ( I'm the Girl, and Unique Space) for disadvantaged young girls Taymara for training costs to upgrade the qualifications of £2,000.00 four existing skipper Youth-Link (Dundee) towards the rent and property costs £6,000.00 Edinburgh, City of (2 records) £11,160.00 Drylaw Telford Community Association towards the running costs of activities for isolated £5,000.00 elderly people Stroke Association towards the running costs of the group, including £6,160.00 outings Falkirk (1 record) £3,500.00 St Andrew's Church of Scotland, Bo'ness towards delivery of one block of after-school £3,500.00 programmes for 8-10 children identified as needing additional support Fife (5 records) £19,648.00 AMS towards the football based fitness sessions for £3,500.00 -

2020-Bos-Annual-Report.Pdf

Bank of Scotland plc Report and Accounts 2020 Member of Lloyds Banking Group Bank of Scotland plc Contents Strategic report 2 Directors’ report 10 Directors 14 Forward looking statements 15 Independent auditors’ report 16 Consolidated income statement 25 Statements of comprehensive income 26 Balance sheets 28 Statements of changes in equity 30 Cash flow statements 32 Notes to the accounts 33 Subsidiaries and related undertakings 122 Registered office: The Mound, Edinburgh EH1 1YZ. Registered in Scotland No. 327000 Bank of Scotland plc Strategic report Principal activities Bank of Scotland plc (the Bank) and its subsidiaries (together, the Group) provide a wide range of banking and financial services. The Group’s revenue is earned through interest and fees on a broad range of financial services products including current and savings accounts, personal loans, credit cards and mortgages within the retail market; loans and other products to commercial, corporate and asset finance customers; and private banking. Business review In the year to 31 December 2020, the Group recorded a profit before tax of £883 million compared to £1,278 million in the year to 31 December 2019. Total income decreased by £886 million, or 15 per cent, to £5,147 million in the year ended 31 December 2020 compared to £6,033 million in 2019 with a £220 million decrease in net interest income combined with a reduction of £666 million in other income. Net interest income was £5,208 million in the year ended 31 December 2020, a decrease of £220 million, or 4 per cent compared to £5,428 million in 2019 reflecting the lower rate environment, actions taken during the year to support customers and reduced levels of customer activity and demand during the coronavirus pandemic.