The Euro Bond Market, July 2001

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mortgage Covered Bonds

COVERED BONDS CREDIT OPINION Deutsche Pfandbriefbank AG - Mortgage 12 July 2019 Covered Bonds New Issue Update to New Issue Report, reflecting data as of 31 March 2019 - German covered bonds Ratings Closing date Exhibit 1 September 2001 Cover Pool (€) Ordinary Cover Pool Assets Covered Bonds (€) Rating 19,855,385,490 Commercial mortgage loans 17,159,274,896 Aa1 TABLE OF CONTENTS Ratings 1 Source: Moody's Investors Service Summary 1 Credit strengths 1 Summary Credit challenges 2 The covered bonds issued by Deutsche Pfandbriefbank AG (the issuer) under the Deutsche Key characteristics 3 Pfandbriefbank AG - Mortgage Covered Bonds programme are full recourse to the issuer and Covered bond description 3 are secured by a cover pool of assets consisting of commercial assets (73.7%), multi-family Covered bond analysis 4 assets (19.4%), supplementary assets (6.8%) and residential assets (0.1%). Cover pool description 8 Cover pool analysis 11 Credit strengths include the full recourse of the covered bonds to the issuer and support Methodology and monitoring 13 provided by the German legal framework for Pfandbriefe, which provides for the issuer's Appendix: Income underwriting and regulation and supervision. valuation 14 Moody's related publications 15 Credit challenges include the high level of dependency on the issuer. As with most covered bonds in Europe, there are few restrictions on the future composition of the cover pool. 56.4% of the commercial mortgages have bullet repayment. Analyst Contacts Francesca Falconi +44.20.7772.1667 Our credit analysis takes into account the cover pool's credit quality, which is reflected in Analyst the collateral score of 6.8%, and the current over-collateralisation (OC) of 17.1% (on an [email protected] unstressed present value basis) as of 31 March 2019. -

Governmental Assistance to the Financial Sector: an Overview of the Global Responses (V9)

Economic Stabilization Advisory Group | October 2, 2009 Governmental Assistance to the Financial Sector: an Overview of the Global Responses (v9) The measures that Governments have taken to protect the financial sector have settled down to a large extent. We have, however, decided to publish a further update on the measures following a renewed interest in developments and the recent G20 Summit. This memorandum summarizes the measures Governments across the world have taken to protect the financial sector and prevent a recession. The measures fall into the following categories: guarantees of bank liabilities; retail deposit guarantees; central bank assistance measures; bank recapitalization through equity investments by private investors and Governments; and open-market or negotiated acquisitions of illiquid or otherwise undesirable assets from weakened financial institutions. The purpose of this publication is to provide an overview of the principal measures that have been taken in the major financial jurisdictions to support the financial system. The first version of this note was published on November 12, 2008. Since then, Governments in some jurisdictions have adopted further measures or amended measures previously adopted. The current version of the note takes into account those measures and is based on information available to us on September 30, 2009. Table of Contents Page AUSTRALIA.......................................................................................................................................................................................................................... -

Hot Spots and Cold

corporate financial management COMMERCIAL PROPERTY Hot spots and cold AFTER TWO YEARS ON THE SKIDS, THE COMMERCIAL PROPERTY MARKET HAS BEEN SHOWING SIGNS OF REVIVAL, BUT IT’S AN UNEVEN TWO-TIER RECOVERY. GRAHAM BUCK REPORTS. he UK commercial property market’s transformation from in July 2009. The drop was dramatic enough to make the sector boom to bust was swift and steep. After peaking in mid-2007 attractive once more to investors, though; over the subsequent 15- as the credit crunch started to bite, capital values slumped by month period the market delivered an impressive 27% in total return 44% over the next two years until the market bottomed out (income plus capital growth). T It’s unlikely that such an outstanding performance will be repeated during the course of the next few years. Prime yields are nearly back to pre-crisis level and may come under pressure as government bond rates rise, says Tony McGough, global head of forecasting at real estate adviser DTZ. “There is also little expectation for strong rental growth outside of London and a few key markets and super-prime sites,” he suggests. The recovery has been driven by two main factors: yield rerating caused by investors’ renewed interest in property – which, in turn, has had a positive impact on capital growth – and strong income returns that have managed to outperform most other UK assets. But the overall picture is rather less positive. Rental values, which reflect demand and supply conditions, have continued to decline. At the end of October 2010 they were down 1.7% on a year earlier; higher rental values for office space in central London were offset by steep falls in many other areas, especially high-street retail properties outside the capital and southern England. -

Response to CESR’S

Response to CESR’s Questionnaire regarding the rating of Structured Finance Instruments The Association of German Pfandbrief Banks (vdp) welcomes the opportunity to comment on the questionnaire regarding the rating of Structured Finance Instruments. The vdp members number among the most important providers of capital for residential and commercial properties as well as for the public sector and its institutions. These funds are mainly raised through the issuance of Pfandbriefe, which are Covered Bonds based on a strong legal basis and a strict special public supervision. Therefore there are significant differences between Pfandbriefe and Structured Finance Instruments like Mortgage Backed Securities (MBS). However, rating agencies often use similar or even the same models in quantifying credit risk and other related risks. Beside Pfandbriefe both true sale and synthetic MBS are used heavily by our members. Hence, they have to deal with rating agencies many times and in many ways. The vdp represents roughly 90% of the Pfandbrief market which underlines its position as one of the leading banking associations in Germany. It should be added that with an outstanding volume of EUR 948.8 billion at the end of 2006 the Pfandbrief ranks at a top position within the European bond market. The Pfandbrief is the benchmark in the European Covered Bond segment and holds 50% of the entire market. B) Questions addressed to the users of ratings and other interested parties Rating process Question 1: Do you consider that access to and availability of structured finance ratings (and any subsequent changes) is satisfactory? In general, Structured Finance issuers face the same problem as those in the plain vanilla market. -

Ecological ESG Pfandbrief Roadshow Presentation

Ecological ESG Pfandbrief Roadshow Presentation October 2018 Münchener Hypothekenbank eG Contents Introducing MünchenerHyp 3 Sustainability 10 Ecological ESG Pfandbrief 18 Appendix 28 Contents 2 “Royal Bank of Bavaria” founded in 1896 strongly enabled and supported by the former Bavarian royal family 122 years successful within the mortgage business Crown of the Kings of Bavaria independent from any corporate group but member of the cooperative FinanzGruppe headquarters in Munich benefit from a strong foothold in Bavaria MünchenerHyp’s Headquarters Introducing MünchenerHyp 3 Key Facts at a Glance systemic important bank under direct ECB supervision: - 39.4 bn Euro total assets - around 500 employees - broad based ownership; no predominant owner - Moody’s issuer rating: Aa3 senior unsecured, A2 junior senior unsecured (03/08/2018) favourable funding by Pfandbrief privilege: - Pfandbrief licence: continuous issuing of benchmark bonds and private placements - second biggest volume of outstanding mortgage Pfandbriefe in Germany - Moody’s Pfandbrief rating: Aaa both public sector and mortgage deep roots within the Cooperative Financial Network (“FinanzGruppe”): - partner of Volksbanken and Raiffeisenbanken in the mortgage lending business - Volksbanken and Raiffeisenbanken as most important business partners and biggest owner group - excellent access to liquidity via the cooperative institutions - strong protection scheme with guarantee fund and guarantee network in the worldwide oldest exclusively private financed protection scheme -

Publication in Accordance with § 28 Pfandbrief Act As at 31 March 2020 1 Index

Publication in accordance with § 28 Pfandbrief Act As at 31 March 2020 1 Index Information on Mortgage Pfandbriefe and its cover assets 3 Information on Public Sector Pfandbriefe and its cover assets 12 Information on Ship Pfandbriefe and its cover assets 20 Minor discrepancies may arise in this report in the calculation of totals and percentages due to rounding. 2 Information on Mortgage Pfandbriefe and its cover assets Outstanding amount of Mortgage Pfandbriefe and its cover assets by nominal value, net present value and risk-adjusted net present value as well as the net present value pursuant to § 6 of the Pfandbrief Net Present Value Regulation (Pfandbrief-Barwertverordnung) for each foreign currency Risk-adjusted Risk-adjusted Risk-adjusted Nominal value Net present value net present value * net present value * net present value * in €m + 250 bp - 250 bp stress of currency Q1 / 2020 Q1 / 2019 Q1 / 2020 Q1 / 2019 Q1 / 2020 Q1 / 2019 Q1 / 2020 Q1 / 2019 Q1 / 2020 Q1 / 2019 Outstandings 2,679.3 3,614.8 2,833.3 3,727.7 2,551.0 3,411.2 3,208.1 4,188.0 2,551.0 3,411.2 Cover pool total 5,954.4 5,795.2 6,416.3 6,318.5 5,988.0 5,853.4 7,062.2 6,952.4 5,987.9 5,853.2 Overcollaterali- 3,275.1 2,180.4 3,582.9 2,590.9 3,437.0 2,442.1 3,854.1 2,764.4 3,436.9 2,442.0 sation Overcollaterali- 122.2 60.3 126.5 69.5 134.7 71.6 120.1 66.0 134.7 71.6 sation in per cent. -

Publication in Accordance with § 28 Pfandbrief Act As at 31 December 2020

Publication in accordance with § 28 Pfandbrief Act As at 31 December 2020 1 Index Information on Mortgage Pfandbriefe and its cover assets 3 Information on Public Sector Pfandbriefe and its cover assets 12 Information on Ship Pfandbriefe and its cover assets 20 Minor discrepancies may arise in this report in the calculation of totals and percentages due to rounding. 2 Information on Mortgage Pfandbriefe and its cover assets Outstanding amount of Mortgage Pfandbriefe and its cover assets by nominal value, net present value and risk-adjusted net present value as well as the net present value pursuant to § 6 of the Pfandbrief Net Present Value Regulation (Pfandbrief-Barwertverordnung) for each foreign currency Risk-adjusted Risk-adjusted Risk-adjusted Nominal value Net present value net present value * net present value * net present value * in €m + 250 bp - 250 bp stress of currency Q4 / 2020 Q4 / 2019 Q4 / 2020 Q4 / 2019 Q4 / 2020 Q4 / 2019 Q4 / 2020 Q4 / 2019 Q4 / 2020 Q4 / 2019 Outstandings 1,988.5 2,679.5 2,156.5 2,821.9 1,908.2 2,533.8 2,473.5 3,211.1 1,908.2 2,533.8 Cover pool total 5,133.4 5,527.1 5,591.0 5,965.1 5,176.5 5,559.3 6,229.2 6,559.6 5,175.4 5,559.1 Overcollaterali- 3,144.9 2,847.6 3,434.6 3,143.2 3,268.3 3,025.4 3,755.7 3,348.5 3,267.3 3,025.3 sation Overcollaterali- 158.2 106.3 159.3 111.4 171.3 119.4 151.8 104.3 171.2 119.4 sation in per cent. -

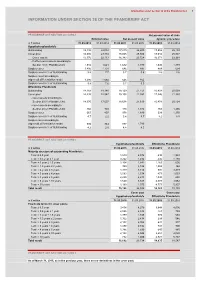

Information Under Section 28 of the Pfandbrief Act 1

Information under Section 28 of the Pfandbrief Act 1 INFORMATION UNDER SECTION 28 OF THE PFANDBRIEF ACT PFANDBRIEF ACT SECTION 28 (1) NO.1 Net present value of risks Nominal value Net present value dynamic procedure in € million 31.03.2015 31.03.2014 31.03.2015 31.03.2014 31.03.2015 31.03.2014 Hypothekenpfandbriefe Outstanding 15,198 22,032 17,419 24,609 17,552 25,193 Cover pool 16,692 23,734 18,065 25,506 18,016 25,847 - Cover assets 15,176 22,113 16,383 23,728 16,371 23,968 - Further cover assets according to Section 19 (1) Pfandbrief Act 1,516 1,621 1,682 1,779 1,645 1,879 Surplus cover 1,495 1,701 646 897 464 654 Surplus cover in % of Outstanding 9.8 7.7 3.7 3.6 2.6 2.6 Surplus cover according to vdp credit differentiation model 1,495 1,668 646 852 Surplus cover in % of Outstanding 9.8 7.6 3.7 3.5 Öffentliche Pfandbriefe Outstanding 14,168 18,140 18,129 21,151 16,808 20,009 Cover pool 14,835 18,547 19,108 22,991 17,346 21,380 - cover assets according to - Section 20 (1) Pfandbrief Act 14,370 17,607 18,638 21,619 16,878 20,124 - cover assets according to - Section 20 (2) Pfandbrief Act 465 939 470 1,372 469 1,255 Surplus cover 667 407 978 1,839 539 1,370 Surplus cover in % of Outstanding 4.7 2.2 5.4 8.7 3.2 6.8 Surplus cover according to vdp credit differentiation model 594 363 877 1,789 Surplus cover in % of Outstanding 4.2 2.0 4.8 8.5 PFANDBRIEF ACT SECTION 28 (1) NO.2 Hypothekenpfandbriefe Öffentliche Pfandbriefe in € million 31.03.2015 31.03.2014 31.03.2015 31.03.2014 Maturity structure of outstanding Pfandbriefe: Term ≤ 0.5 year -

Emerging Market Corporate Bonds Accessing Some of the World’S Potential Growth Opportunities Fall 2013

Emerging Market Corporate Bonds Accessing some of the world’s potential growth opportunities Fall 2013 Contents Executive summary 03 Introduction 04 Emerging Market corporate bonds 06 - 10 key characteristics 06 Conclusion 12 - A compelling asset class 12 Risks 13 Aberdeen’s investment process for Emerging Market corporates 14 Appendix 1 15 - FAQs 15 Appendix 2 16 - Indices 16 Appendix 3 17 - Regional characteristics 17 01 of 20 City people - a street scene. 44 million people join urban populations in developing Asian countries each year. 20,000 new dwellings and 250km of new roads are constructed every day. Source: Asian Development Bank, The Economist, 2013 02 of 20 Executive summary Emerging Markets Emerging Market corporate debt – why are they attractive? – understanding the risks • We believe Emerging Markets (EM) present some of the world’s most • EM corporate bondholders face the same issues of transparency and dynamic growth opportunities. Abundant natural resources, favourable corporate governance as EM equity investors, albeit that market demographics and structural credit improvement combined with fiscal liquidity and bond structure are areas of greater consideration. and corporate reforms have led to improving economic fundamentals • In terms of capital structure, priority access to cash flow is crucial in (i.e. good corporate balance sheets, strong fiscal discipline and solid determining default and recovery scenarios, which in turn drives the growth dynamics). relative valuation of a bond. It comes down to the exact position of the • We believe investing in EM corporate bonds is attractive because we debt within the company structure, which can often be more consider these companies fundamentally sound and they operate in complicated to discern in EM companies. -

The Transposition of the EU CB-Harmonization Into the German Pfandbrief Act

The Transposition of the EU CB-harmonization into the German Pfandbrief Act Sascha Kullig, Member of the Management Board Association of German Pfandbrief Banks, vdp December 2020 2. Amendments to the Pfandbrief Act Timeline CBD-Transposition Act (CBDUmsG) transitional period latest application of MoF-Draft amended Art 129 CRR Bundestag and BT- German MoF publishes draft ab Q3 2019 of Pfandbrief Act amendments Finance Committee enactment Bundestag 2.10.2020 Dec 2020 Mar 2021 ab8 Q3July 2021 8 July 2022 tbd tbd offen 2019 Governmental draft Bundesrat Deadline transposition for (Federal Council) national legislators ▪ All mandatory provisions of the EU-CB Directive and the requirements according to Art. 129 CRR will be implemented in the PfandBG. Consequently, Pfandbrief will continue to benefit from all EU regulatory privileges. ▪ Entry into force • Art. 1 = amendments to the Pfandbrief Act – the day after promulgation, 8 July 2021, at the latest. • Art. 2 = further amendments to Pfandbrief Act – entry into force 8 July 2022. Seite 2 2. Amendments to the Pfandbrief Act § 4 PfandBG – calculation of cover, overcollateralization What will be changed to be introduced ▪ Net present value OC will become a lump sum for costs of cover 2021 pool administrator. (= implementation of Art. 15 (3) (d) CBD) ▪ Consideration of smaller redemption values for (central-) bank 2021 accounts. (= beyond CBD; reflecting negative interest rates) ▪ Non-performing unsecured claims may not be included in the 2021 calculation of cover. (= implementation of Art. 15 (4) CBD) ▪ Introduction of 2% nominal overcollateralization for Mortgage and Public Pfandbrief, 5% for Ship and Aircraft Pfandbrief. 2022 (= national, optional decision following Art. -

The German Pfandbrief System Facing the Financial Crisis

The German Pfandbrief system facing the financial crisis Author: Prof. Dr.rer.pol. Stefan Kofner, MCIH TRAWOS: Institut for Transformation, Housing and Social Spatial Development date For the European Network of Housing Research International Housing Conference, Prague, Czech Republic 28th June – 1st July 2009 1 Abstract: Despite of the good state of German primary mortgage credit markets the liquidity of the German Pfandbrief market has suffered after the collapse of the investment bank Lehman brothers. At the most the market was not able to absorb larger volumes of Pfandbrief sales since then. Also the emission market has suffered. The risk premiums as compared with gov- ernment bonds have risen to levels never seen before. Since the Pfandbrief as a special and highly regulated form of a covered bond has numerous characteristics meant to minimize the default risk the phenomena of partial illiquidity and rising risk premiums demand explanation. Presumably doubts about the quality of the cover- ing values have only played a minor role here. It seems that investors do not trust the stability of the issuers any more. Also the massive emission volumes of government bonds and guaran- teed bank obligations combined with deposit guaranties might have harmed the Pfandbrief market. The Pfandbrief has been a stable source for the refinancing of mortgage credits for centuries. In view of the complete collapse of other sources of refinance the Pfandbrief system could even serve as a blueprint for the future of mortgage credit refinance around the world. We thus need to investigate carefully the necessity of re-regulation of Pfandbrief banks. -

German Covered Bonds Overview and Risk Analysis of Pfandbriefe Series: Springerbriefs in Finance

springer.com Ralf Werner, Manuela Spangler German Covered Bonds Overview and Risk Analysis of Pfandbriefe Series: SpringerBriefs in Finance Comprehensive analysis of Pfandbrief-related risks and the legal framework of Pfandbriefe Extensive list of more than 200 Pfandbrief-related references providing an ideal starting point for further research First monograph (outside lobby and interest groups) on the German Pfandbrief, representing the only monograph with unbiased information on this product The Pfandbrief, a mostly triple-A rated German bank debenture, has become the blueprint of many covered bond models in Europe and beyond. The Pfandbrief is collateralized by long- term assets such as property mortgages or public sector loans as stipulated in the Pfandbrief Act. With a history that goes back to the 18th century and a high market share in today’s 2014, IX, 82 p. 30 illus. covered bond markets, the German Pfandbrief is the most established covered bond. Until today, no single Pfandbrief has ever defaulted. Even though Pfandbriefe have survived the financial crisis comparably unharmed, investors have become more sensitive regarding the Printed book creditworthiness of the corresponding issuer and sovereign, the strength of the legal (or Softcover contractual) framework and the quality of the cover pool serving as collateral. This monograph 54,99 € | £49.99 | $69.99 provides a structured in-depth analysis of the legal framework and the risks inherent in a [1]58,84 € (D) | 60,49 € (A) | CHF Pfandbrief, taking into consideration recent market developments. Starting from the legal 65,00 framework, the German Pfandbrief is introduced without requiring prior knowledge. Covered eBook bond related risks are explained in detail and their relevance to the Pfandbrief is thoroughly 46,00 € | £39.99 | $54.99 discussed with focus on the two most common Pfandbrief types, mortgage and public [2] 46,00 € (D) | 46,00 € (A) | CHF Pfandbriefe.