Maternal Care in Australian Oncomerine Shield Bugs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Insetos Do Brasil

COSTA LIMA INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO HEMÍPTEROS ESCOLA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA SÉRIE DIDÁTICA N.º 3 - 1940 INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO HEMÍPTEROS A. DA COSTA LIMA Professor Catedrático de Entomologia Agrícola da Escola Nacional de Agronomia Ex-Chefe de Laboratório do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz INSETOS DO BRASIL 2.º TOMO CAPÍTULO XXII HEMÍPTEROS ESCOLA NACIONAL DE AGRONOMIA SÉRIE DIDÁTICA N.º 3 - 1940 CONTEUDO CAPÍTULO XXII PÁGINA Ordem HEMÍPTERA ................................................................................................................................................ 3 Superfamília SCUTELLEROIDEA ............................................................................................................ 42 Superfamília COREOIDEA ............................................................................................................................... 79 Super família LYGAEOIDEA ................................................................................................................................. 97 Superfamília THAUMASTOTHERIOIDEA ............................................................................................... 124 Superfamília ARADOIDEA ................................................................................................................................... 125 Superfamília TINGITOIDEA .................................................................................................................................... 132 Superfamília REDUVIOIDEA ........................................................................................................................... -

Brief Report Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (4): 863–868, 2016

Brief report Acta Palaeontologica Polonica 61 (4): 863–868, 2016 A new pentatomoid bug from the Ypresian of Patagonia, Argentina JULIÁN F. PETRULEVIČIUS A new pentatomoid heteropteran, Chinchekoala qunita gen. (Wilf et al. 2003). It consists of a single specimen, holotype et sp. nov. is described from the lower Eocene of Laguna MPEF-PI 944a–b, with dorsal and ventral sides, collected from del Hunco, Patagonia, Argentina. The new genus is mainly pyroclastic debris of the plant locality LH-25, latitude 42°30’S, characterised by cephalic characters such as the mandibular longitude 70°W (Wilf 2012; Wilf et al. 2003, 2005). The locality plates surpassing the clypeus and touching each other in dor- was dated using 40Ar/39Ar by Wilf et al. (2005) and recalculated sal view; head wider than long; and remarkable characters by Wilf (2012), giving an age of 52.22 ± 0.22 (analytical 2 σ), related to the eyes, which are surrounded antero-laterally ± 0.29 (full 2 σ) Ma. The specimen was originally partly covered and posteriorly by the anteocular processes and the prono- by sediment and was prepared with a pneumatic hammer. It was tum, as well as they extend medially more than usual in the drawn with a camera lucida attached to a Wild M8 stereomicro- Pentatomoidea. This is the first pentatomoid from the Ypre- scope and photographed with a Nikon SMZ800 with a DS-Vi1 sian of Patagonia and the second from the Eocene in the re- camera. For female genitalia nomenclature I use valvifers VIII gion, being the unique two fossil pentatomoids in Argentina. -

A Stink Bug Euschistus Quadrator Rolston (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 Sara A

EENY-523 A Stink Bug Euschistus quadrator Rolston (Insecta: Hemiptera: Pentatomidae)1 Sara A. Brennan, Joseph Eger, and Oscar E. Liburd2 Introduction in the membranous area of the hemelytra, a characteristic present in other Euschistus species. Euschistus quadrator Rolston was described in 1974, with specimens from Mexico, Texas, and Louisiana. Euschistus quadrator was not found in Florida until 1992. It has since spread throughout the state as well as becoming an agricultural pest of many fruit, vegetable, and nut crops in the southeastern United States. It has a wide host range, but is most commonly found in cotton, soybean and corn. Euschistus quadrator has recently become a more promi- nent pest with the introduction of crops such as Bt cotton and an increase in the usage of biorational or reduced-risk pesticides. Distribution Euschistus quadrator is originally from Texas and Mexico, and has since been reported in Louisiana, Georgia, and Florida. Description Figure 1. Dorsal view of Euschistus quadrator Rolston; adult male (left) Adults and female (right), a stink bug. Credits: Lyle Buss, University of Florida The adults are shield-shaped and light to dark brown in color. They are smaller than many other members of the ge- Eggs nus, generally less than 11 mm in length and approximately Euschistus quadrator eggs are initially semi-translucent and 5 mm wide across the abdomen. They are similar in size to light yellow, and change color to red as the eggs mature. The Euschistus obscurus. Euschistus quadrator lacks dark spots micropylar processes (fan-like projections around the top 1. This document is EENY-523, one of a series of the Department of Entomology and Nematology, UF/IFAS Extension. -

Heteroptera: Coreidae: Coreinae: Leptoscelini)

Brailovsky: A Revision of the Genus Amblyomia 475 A REVISION OF THE GENUS AMBLYOMIA STÅL (HETEROPTERA: COREIDAE: COREINAE: LEPTOSCELINI) HARRY BRAILOVSKY Instituto de Biología, UNAM, Departamento de Zoología, Apdo Postal 70153 México 04510 D.F. México ABSTRACT The genus Amblyomia Stål is revised and two new species, A. foreroi and A. prome- ceops from Colombia, are described. New host plant and distributional records of A. bifasciata Stål are given; habitus illustrations and drawings of male and female gen- italia are included as well as a key to the known species. The group feeds on bromeli- ads. Key Words: Insecta, Heteroptera, Coreidae, Leptoscelini, Amblyomia, Bromeliaceae RESUMEN El género Amblyomia Stål es revisado y dos nuevas especies, A. foreroi y A. prome- ceops, recolectadas en Colombia, son descritas. Plantas hospederas y nuevas local- idades para A. bifasciata Stål son incluidas; se ofrece una clave para la separación de las especies conocidas, las cuales son ilustradas incluyendo los genitales de ambos sexos. Las preferencias tróficas del grupo están orientadas hacia bromelias. Palabras clave: Insecta, Heteroptera, Coreidae, Leptoscelini, Amblyomia, Bromeli- aceae The neotropical genus Amblyomia Stål was previously known from a single Mexi- can species, A. bifasciata Stål 1870. In the present paper the genus is redefined to in- clude two new species collected in Colombia. This genus apparently is restricted to feeding on members of the Bromeliaceae, and specimens were collected on the heart of Ananas comosus and Aechmea bracteata. -

Barbed Wire Vine

Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Compiled by: Michael Fox www.megoutlook.org/flora-fauna/ © 2015-17 Creative Commons – free use with attribution to Mt Gravatt Environment Group Ants Dolichoderinae Iridomyrmex sp. Small Meat Ant Attendant “Kropotkin” ants with caterpillar of Imperial Hairstreak butterfly. Ants provide protection in return for sugary fluids secreted by the caterpillar. Note the strong jaws. These ants don’t sting but can give a powerful bite. Kropotkin is a reference to Russian biologist Peter Kropotkin who proposed a concept of evolution based on “mutual aid” helping species from ants to higher mammals survive. 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 1 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Opisthopsis rufithorax Black-headed Strobe Ant 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 2 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Camponotus consobrinus Banded Sugar Ant Size 10mm Eggs in rotting log Formicinae Camponotus nigriceps Black-headed Sugar Ant 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 3 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 4 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis ammon Golden-tailed Spiny Ant Large spines at rear of thorax Nest 22-Aug-17 Insects Beetles and Bugs - ver 5.4 Page 5 of 51 Mt Gravatt Environment Group – www.megoutlook.wordpress.com Insects, beetles, bugs and slugs of Mt Gravatt Conservation Reserve Formicinae Polyrhachis australis Rattle Ant Black Weaver Ant or Dome-backed Spiny Ant Feeding on sugar secretions produced by Redgum Lerp Psyllid. -

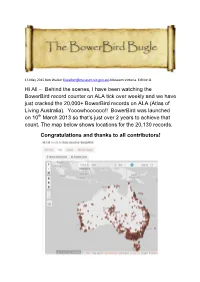

Behind the Scenes, I Have Been Watching the Bowerbird Record

15 May 2015 Ken Walker ([email protected]) Museum Victoria. Edition 8. Hi All – Behind the scenes, I have been watching the BowerBird record counter on ALA tick over weekly and we have just cracked the 20,000+ BowerBird records on ALA (Atlas of Living Australia). Yooowhoooooo!! BowerBird was launched on 10th March 2013 so that’s just over 2 years to achieve that count. The map below shows locations for the 20,130 records. Congratulations and thanks to all contributors! From a purely funding analysis point of view, the initial ALA grant to develop BowerBird was $350,000 which at 20,130 records is currently returning per record at a cost of $17.38 and that per record cost will only get lower as more BowerBird records are added and uploaded. For some species on ALA, BowerBird provides the only distributional species data points: For other species on ALA, BowerBird provides the only species image for species on ALA: From a Biosecurity point of view of tracking exotic species, BowerBird has supplied all records post 2007 for the exotic South African Carder bee. All of the blue dots represent BowerBird records. Other than the great biodiversity results that BowerBird delivers through ALA, there are a myriad of other intangible benefits that come from the BowerBird website. Intangibles such as the member’s conversations, identification discussions, the friendships, the biological statements and the generated innate knowledge. One particular “intangible”, I would like to tell you about here. The PBCRC (Plant Biosecurity, Cooperative Research Centre) has a theme called “Building Resilience through Remote Indigenous Engagement”. -

Bird Predation on Periodical Cicadas in Ozark Forests: Ecological Release for Other Canopy Arthropods?

Studies in Avian Biology No. 13:369-374, 1990. BIRD PREDATION ON PERIODICAL CICADAS IN OZARK FORESTS: ECOLOGICAL RELEASE FOR OTHER CANOPY ARTHROPODS? FREDERICK M. STEPHEN, GERALD W. WALLIS, AND KIMBERLY G. SMITH Abstract. Population dynamics of canopy arthropods were monitored in two upland forests in the Arkansas Ozarks during spring and summer of 1984-1986 to test whether the emergence of adult 13-year periodical cicadas on one site during late spring in 1985 would disrupt normal patterns of bird predation on canopy arthropods, resulting in ecological release for those prey populations. Canopy arthropods on foliage of oak, hickory, and eastern redcedar were sampled weekly beginning in June 1984, and April 1985 and 1986, and continuing through August in all years. We classed arthropods into four broad guilds based on foraging mode (chewers, suckers, spiders, and lepidopterous larvae) and expressed densities as number of individuals per kg of foliage sampled. Two-way analysis of variance revealed no significant treatment effects for densities of chewing, sucking, or lepidopteran larval guilds. A significant interaction of mean density between sites among years was detected for the spider guild, but not when cicadas were present, indicating that ecological release did not occur. We trace the development of the notion that bird populations are capable of affecting prey population levels, and discuss those ideas in light of our results, which suggest that birds have little impact upon their arthropod prey in Ozark forests. Kev Words: Arkansas: canonv arthronods: ecological release; guilds; insect sampling; Magicicada; Ozarks; periodical cicadas; predation. _ ’ One of the most predictable events in nature (Mugicicudu tredecim Walsh and Riley, M. -

A New Pupillarial Scale Insect (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Eriococcidae) from Angophora in Coastal New South Wales, Australia

Zootaxa 4117 (1): 085–100 ISSN 1175-5326 (print edition) http://www.mapress.com/j/zt/ Article ZOOTAXA Copyright © 2016 Magnolia Press ISSN 1175-5334 (online edition) http://doi.org/10.11646/zootaxa.4117.1.4 http://zoobank.org/urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:5C240849-6842-44B0-AD9F-DFB25038B675 A new pupillarial scale insect (Hemiptera: Coccoidea: Eriococcidae) from Angophora in coastal New South Wales, Australia PENNY J. GULLAN1,3 & DOUGLAS J. WILLIAMS2 1Division of Evolution, Ecology & Genetics, Research School of Biology, The Australian National University, Acton, Canberra, A.C.T. 2601, Australia 2The Natural History Museum, Department of Life Sciences (Entomology), London SW7 5BD, UK 3Corresponding author. E-mail: [email protected] Abstract A new scale insect, Aolacoccus angophorae gen. nov. and sp. nov. (Eriococcidae), is described from the bark of Ango- phora (Myrtaceae) growing in the Sydney area of New South Wales, Australia. These insects do not produce honeydew, are not ant-tended and probably feed on cortical parenchyma. The adult female is pupillarial as it is retained within the cuticle of the penultimate (second) instar. The crawlers (mobile first-instar nymphs) emerge via a flap or operculum at the posterior end of the abdomen of the second-instar exuviae. The adult and second-instar females, second-instar male and first-instar nymph, as well as salient features of the apterous adult male, are described and illustrated. The adult female of this new taxon has some morphological similarities to females of the non-pupillarial palm scale Phoenicococcus marlatti Cockerell (Phoenicococcidae), the pupillarial palm scales (Halimococcidae) and some pupillarial genera of armoured scales (Diaspididae), but is related to other Australian Myrtaceae-feeding eriococcids. -

Melon Aphid Or Cotton Aphid, Aphis Gossypii Glover (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphididae)1 John L

EENY-173 Melon Aphid or Cotton Aphid, Aphis gossypii Glover (Insecta: Hemiptera: Aphididae)1 John L. Capinera2 Distribution generation can be completed parthenogenetically in about seven days. Melon aphid occurs in tropical and temperate regions throughout the world except northernmost areas. In the In the south, and at least as far north as Arkansas, sexual United States, it is regularly a pest in the southeast and forms are not important. Females continue to produce southwest, but is occasionally damaging everywhere. Be- offspring without mating so long as weather allows feeding cause melon aphid sometimes overwinters in greenhouses, and growth. Unlike many aphid species, melon aphid is and may be introduced into the field with transplants in the not adversely affected by hot weather. Melon aphid can spring, it has potential to be damaging almost anywhere. complete its development and reproduce in as little as a week, so numerous generations are possible under suitable Life Cycle and Description environmental conditions. The life cycle differs greatly between north and south. In the north, female nymphs hatch from eggs in the spring on Egg the primary hosts. They may feed, mature, and reproduce When first deposited, the eggs are yellow, but they soon parthenogenetically (viviparously) on this host all summer, become shiny black in color. As noted previously, the eggs or they may produce winged females that disperse to normally are deposited on catalpa and rose of sharon. secondary hosts and form new colonies. The dispersants typically select new growth to feed upon, and may produce Nymph both winged (alate) and wingless (apterous) female The nymphs vary in color from tan to gray or green, and offspring. -

Chapter 12. Estimating the Host Range of the Tachinid Trichopoda Giacomellii, Introduced Into Australia for Biological Control of the Green Vegetable Bug

__________________________________ ASSESSING HOST RANGES OF PARASITOIDS AND PREDATORS CHAPTER 12. ESTIMATING THE HOST RANGE OF THE TACHINID TRICHOPODA GIACOMELLII, INTRODUCED INTO AUSTRALIA FOR BIOLOGICAL CONTROL OF THE GREEN VEGETABLE BUG M. Coombs CSIRO Entomology, 120 Meiers Road, Indooroopilly, Queensland, Australia 4068 [email protected] BACKGROUND DESCRIPTION OF PEST INVASION AND PROBLEM Nezara viridula (L.) is a cosmopolitan pest of fruit, vegetables, and field crops (Todd, 1989). The native geographic range of N. viridula is thought to include Ethiopia, southern Europe, and the Mediterranean region (Hokkanen, 1986; Jones, 1988). Other species in the genus occur in Africa and Asia (Freeman, 1940). First recorded in Australia in 1916, N. viridula soon be- came a widespread and serious pest of most legume crops, curcubits, potatoes, tomatoes, pas- sion fruit, sorghum, sunflower, tobacco, maize, crucifers, spinach, grapes, citrus, rice, and mac- adamia nuts (Hely et al., 1982; Waterhouse and Norris, 1987). In northern Victoria, central New South Wales, and southern Queensland, N. viridula is a serious pest of soybeans and pecans (Clarke, 1992; Coombs, 2000). Immature and adult bugs feed on vegetative buds, devel- oping and mature fruits, and seeds, causing reductions in crop quality and yield. The pest status of N. viridula in Australia is assumed to be partly due to the absence of parasitoids of the nymphs and adults. No native Australian tachinids have been found to parasitize N viridula effectively, although occasional oviposition and development of some species may occur (Cantrell, 1984; Coombs and Khan, 1997). Previous introductions of biological control agents to Australia for control of N. viridula include Trichopoda pennipes (Fabricius) and Trichopoda pilipes (Fabricius) (Diptera: Tachinidae), which are important parasitoids of N. -

Identification, Biology, Impacts, and Management of Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Soybean and Corn in the Midwestern United States

Journal of Integrated Pest Management (2017) 8(1):11; 1–14 doi: 10.1093/jipm/pmx004 Profile Identification, Biology, Impacts, and Management of Stink Bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) of Soybean and Corn in the Midwestern United States Robert L. Koch,1,2 Daniela T. Pezzini,1 Andrew P. Michel,3 and Thomas E. Hunt4 1 Department of Entomology, University of Minnesota, 1980 Folwell Ave., Saint Paul, MN 55108 ([email protected]; Downloaded from https://academic.oup.com/jipm/article-abstract/8/1/11/3745633 by guest on 08 January 2019 [email protected]), 2Corresponding author, e-mail: [email protected], 3Department of Entomology, Ohio Agricultural Research and Development Center, The Ohio State University, 210 Thorne, 1680 Madison Ave. Wooster, OH 44691 ([email protected]), and 4Department of Entomology, University of Nebraska, Haskell Agricultural Laboratory, 57905 866 Rd., Concord, NE 68728 ([email protected]) Subject Editor: Jeffrey Davis Received 12 December 2016; Editorial decision 22 March 2017 Abstract Stink bugs (Hemiptera: Heteroptera: Pentatomidae) are an emerging threat to soybean and corn production in the midwestern United States. An invasive species, the brown marmorated stink bug, Halyomorpha halys (Sta˚ l), is spreading through the region. However, little is known about the complex of stink bug species associ- ated with corn and soybean in the midwestern United States. In this region, particularly in the more northern states, stink bugs have historically caused only infrequent impacts to these crops. To prepare growers and agri- cultural professionals to contend with this new threat, we provide a review of stink bugs associated with soybean and corn in the midwestern United States. -

Insects" from Atlas of the Sand Hills

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Entomology Museum, University of Nebraska State October 1998 "Insects" from Atlas of the Sand Hills Brett C. Ratcliffe University of Nebraska-Lincoln, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologypapers Part of the Entomology Commons Ratcliffe, Brett C., ""Insects" from Atlas of the Sand Hills" (1998). Papers in Entomology. 44. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/entomologypapers/44 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Museum, University of Nebraska State at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Entomology by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Insects Brett C. Ratcliffe Curator of Entomology University of Nebraska State Museum What is life? It is the flash of the firefly do the job nor adequate resources devoted sects in the Sand Hills tolerate drier and in the night. It is the breath of a buf- to such an undertaking. No one knows, windier conditions and greater solar ra- falo in the winter time. It is the little therefore, how many species of insects diation. They have also been successful shadow which runs across the grass occur in Nebraska, although the number in surviving the periodic fires that are so and loses itself in the sunset. undoubtedly reaches the thousands. necessary for maintaining native grass- However, a number of specific in- lands. In fact, the mosaic of habitats par- —Crowfoot, 1890, Blackfoot sect groups in Nebraska have been sur- tially created by fire has probably con- Confederacy Spokesman veyed, including in the Sand Hills.