Religion, Cults & Rituals

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

“Proud to Be Norwegian”

(Periodicals postage paid in Seattle, WA) TIME-DATED MATERIAL — DO NOT DELAY Travel In Your Neighborhood Norway’s most Contribute to beautiful stone Et skip er trygt i havnen, men det Amundsen’s Read more on page 9 er ikke det skip er bygget for. legacy – Ukjent Read more on page 13 Norwegian American Weekly Vol. 124 No. 4 February 1, 2013 Established May 17, 1889 • Formerly Western Viking and Nordisk Tidende $1.50 per copy News in brief Find more at blog.norway.com “Proud to be Norwegian” News Norway The Norwegian Government has decided to cancel all of commemorates Mayanmar’s debts to Norway, nearly NOK 3 billion, according the life of to Mayanmar’s own government. The so-called Paris Club of Norwegian creditor nations has agreed to reduce Mayanmar’s debts by master artist 50 per cent. Japan is cancelling Edvard Munch debts worth NOK 16.5 billion. Altogether NOK 33 billion of Mayanmar’s debts will be STAFF COMPILATION cancelled, according to an Norwegian American Weekly announcement by the country’s government. (Norway Post) On Jan. 23, HM King Harald and other prominent politicians Statistics and cultural leaders gathered at In 2012, the total river catch of Oslo City Hall to officially open salmon, sea trout and migratory the Munch 150 celebration. char amounted to 503 tons. This “Munch is one of our great is 57 tons, or 13 percent, more nation-builders. Along with author than in 2011. In addition, 91 tons Henrik Ibsen and composer Edvard of fish were caught and released. Grieg, Munch’s paintings lie at the The total catch consisted of core of our cultural foundation. -

140914 Arrangørdagbok Gimletroll 2014-15.Xlsx

Arrangørdagbok for Gimletroll IK 2014‐2015 Tid Ansvarlige Kampnr Respin Avdeling Bane Hjemmelag Bortelag Ansvarlige Obs TIRSDAG 23.09.2014 1900 55K0503007 1195139 5. divisjon Kvinner Avd. 2 Agder Aquarama Gimletroll AK 28 3 Damelaget Damelaget ONSDAG 24.09.2014 2000 55J1304001 1168324 Jenter 13 Avdeling B 2 Havlimyrhallen Gimletroll 2 Fløy 2 Jenter 13 Jenter 13 ONSDAG 08.10.2014 1700 Leif E 55HU‐01001 1134590 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen Grane Arendal 2 Vindbjart v 1740 Leif E 55HU‐01002 1134591 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen MHI Grane Arendal 1 Leif E 1820 Leif E 55HU‐01004 1134593 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen Gimletroll Grane Arendal 2 Leif E 1900 Leif E 55HU‐01003 1134592 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen Vindbjart Våg Leif E 1940 Leif E 55HU‐01005 1134594 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen Greipstad MHI Leif E 2020 Leif E 55HU‐01006 1134595 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen Grane Arendal 1 Imås Leif E 2100 Leif E 55HU‐01008 1134597 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen Imås Gimletroll Leif E 2140 Leif E 55HU‐01007 1134596 Håndball for utviklingshemmede Agder Odderneshallen Våg Greipstad Leif E SØNDAG 12.10.2014 1200 Jenter 12 55J1205008 1165085 Jenter 12 Avdeling 5 Havlimyrhallen Gimletroll 3 Torridal * Jenter 12 1300 Jenter 13 55J1304020 1168343 Jenter 13 Avdeling B 2 Havlimyrhallen Gimletroll 2 Kristiansand 2 Jenter 13 1400 55J1401012 1195338 Jenter 14 Avdeling A Agder Havlimyrhallen Gimletroll Strømmen‐Glimt/Hisøy -

Virksomhetens Navn

Levanger kommune Møteinnkalling Utvalg: Driftsutvalget Møtested: 1045, Levanger rådhus Dato: 12.02.2020 Tid: 12:00 MERK! Tidspunkt! Faste medlemmer er med dette kalt inn til møtet. Den som har lovlig forfall, eller er inhabil i noen av sakene, må melde fra så snart som mulig med begrunnelse, på e-post: [email protected] Varamedlemmer møter etter nærmere avtale. Saksnr Innhold PS 5/20 Godkjenning/signering av protokoll PS 6/20 Prioritering av spillemiddelsøknader til idrettsanlegg 2020 PS 7/20 Kjøp av sykehjemsplasser PS 8/20 Opprettelse av inkluderingstilskudd i Levanger kommune PS 9/20 Barnetrygd - beregning av økonomisk sosialhjelp FO 4/20 Spørsmål fra Karl M. Buchholdt (V) - Ungdomsskolen i Levanger - fremmedspråk Orienteringer/tema: • «Hvordan skape gode politiske arbeidsprosesser i politiske utvalg?» v/Espen Leirset, stipendiat Nord universitet (12.00-13.00) • Status sak om matproduksjon i Levanger v/kommunalsjef Kristin Bratseth (10 min) • Orientering om temaplanen for legetjenesten i Levanger v/enhetsleder Institusjonstjenester Merete Rønningen (20 min) Levanger, den 5. februar 2020 sign. Janne K. Jørstad Larsen leder Levanger kommune – Driftsutvalget 12.02.20 - Sakliste PS 5/20 Godkjenning/signering av protokoll 2 av 14 Levanger kommune – Driftsutvalget 12.02.20 - Sakliste Levanger kommune Sakspapir Prioritering av spillemiddelsøknader til idrettsanlegg 2020 Saksbehandler: Kjersti Nordberg Arkivref: E-post: [email protected] 2020/118 - / Tlf.: 74 05 28 49 Saksordfører: (Ingen) Utvalg Møtedato Saksnr. Driftsutvalget -

Playing History Play and Ideology in Spelet Om Heilag Olav

NORDIC THEATRE STUDIES Vol. 31, No. 1. 2019, 108-123 Playing History Play and ideology in Spelet om Heilag Olav JULIE RONGVED AMUNDSEN ABSTRACT Spelet om Heilag Olav, also called Stiklestadspelet, is Norway’s longest running historical spel. Spels are Norwegian annual outdoor performances about a historical event from the local place where the spel is performed. Spelet om Heilag Olav is about the martyr death of King Olav Harladsson at Stiklestad in 1030, which is said to have brought Christianity to Norway. The spel is subject to conservative aesthetics where both the history of medieval Norway and the spel’s own inherent history guarantees that there will not be big changes in the performance from year to year. This conservative aesthetics makes room for a certain form of nostalgia that can be linked to play. The spel makes use of more serious sides of play. In the theories of Victor Turner, play is connected to the liminoid that differs from the liminal because the liminoid is connected to choice while the liminal is duty. The spel is liminoid but it can be argued that the liminoid has a mimetic relationship to the liminal and through play the spel can make use of several liminal qualities without becoming an actually transforming event. One of the main aesthetic ideas of the spel is authenticity. That this today feels old fashioned is legitimized through the necessity of authenticity and authenticity’s connection to play. Through the use of Žižek’s theories of ideology and his term of failure, the article argues that the failure of creating totalities is inherent to theatre, and that this failure is play. -

The DEER-WOOD Project North-Trøndelag County, Norway

The DEER-WOOD project North-Trøndelag county, Norway Skogeierforeninga Nord (Forest Owners’ Association, North) 1. Background – Nordic/ Scottish Collaboration. In February 1998, Inn-Trøndelag Forest Owners’ Association (I-T FOA, later merged into Forest Owners’ Association North) was asked by the Norwegian Forest Owners’ Federation (NFOF) to participate in a project on Managing deers across multiple land ownerships. The background for the question was: 1) that NFOF had taken the responsibility on behalf of Nordic Council of Ministers to establish cooperation between Scottish and Nordic units in forestry, 2) that an initiative had recently been made by Forestry Commission, Edinburgh, on a collaboration on deer management, 3) that an NPP-funding system had been established. Statistics of elk culled in Nord-Trøndelag county (N-T) show that around 1960 1500 elks were culled annually, 1970 600, since then an even growth so for the recent years the annual number culled has reached 4000 or more. In 1997 the venison value amounted to NOK mio 37, while the road side value of timber harvested was NOK mio 184 (average for the 90-es NOK mio 230). Since early 80-es N-T has had the following aim for deer management: ”The deer management should be practiced in order to obtain the highest possible level of production and of venison. At the same time eventual damage on agriculture, horticulture, forestry and traffic should be kept on an acceptable level. There is a general agreement that the management has been successful regarding raising the number of moose and their productivity. The number now is on a historically speaking high level. -

Battle of Stiklestad: Supporting Virtual Heritage with 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments and Mobile Devices in Educational Settings

Archived at the Flinders Academic Commons http://dspace.flinders.edu.au/dspace/ Originally published at: Proceedings of Mobile and Ubiquitous Technologies for Learning (UBICOMM 07), Papeete, Tahiti, 04-09 November 2007, pp. 197-203 Copyright © 2007 IEEE. Published version of the paper reproduced here in accordance with the copyright policy of the publisher. Personal use of this material is permitted. However, permission to reprint/republish this material for advertising or promotional purposes or for creating new collective works for resale or redistribution to servers or lists, or to reuse any copyrighted component of this work in other works must be obtained from the IEEE. International Conference on Mobile Ubiquitous Computing, Systems, Services and Technologies Battle of Stiklestad: Supporting Virtual Heritage with 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments and Mobile Devices in Educational Settings Ekaterina Prasolova-Førland Theodor G. Wyeld Monica Divitini, Anders Lindås Norwegian University of Adelaide University Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Adelaide, Australia Science and Technology, Trondheim, Norway [email protected] Trondheim, Norway [email protected] [email protected], [email protected] Abstract sociological significance. From reconstructions recording historical information about these sites a 3D Collaborative Virtual Environments (CVEs) realistic image of how these places might have looked in the past can be created. This also allows inhabiting have been widely used for preservation of cultural of these reconstructed spaces with people and artifacts heritage, also in an educational context. This paper for users to interact with. All these features can act as a presents a project where 3D CVE is augmented with valuable addition to a ‘traditional’ educational process mobile devices in order to support a collaborative in history and related subjects. -

Konsesjonssøknad Delstrekning Klæbu-Namsos

Konsesjonssøknad Spenningsoppgradering i Midt-Norge Delstrekning Klæbu-Namsos Søknad om konsesjon for ombygging fra 300 til 420 kV Juni 2010 Fosnes Høylandet Flatanger Namsos OverhallaGrong Osen Grong Namdalseid Roan Snåsa Steinkjer Åfjord Verran Inderøy Bjugn Mosvik Rissa Verdal Levanger Leksvik Frosta Stjørdal Trondheim Malvik Meråker Skaun Melhus Klæbu Selbu Juni 2010 Konsesjonssøknad. Spenningsoppgradering. 300/420 kV-ledning Klæbu - Namsos Forord Som følge av behovet for å sikre en stabil strømforsyning, ønsket om tilrettelegging for utbygging av ny grønn kraft samt målet om en felles kraftpris i Norge, er det nødvendig å øke overføringskapasiteten i sentralnettet. Statnett SF legger derfor med dette frem søknad om konsesjon, ekspropriasjonstillatelse og forhåndstiltredelse for spenningsoppgradering (ombygging) av eksisterende 300 kV-ledning Klæbu – Verdal – Ogndal – Namsos fra Klæbu transformatorstasjon i Klæbu kommune, via Verdal og Ogndal transformatorstasjoner i henholdsvis Verdal og Steinkjer kommuner, til Namsos transformatorstasjon i Overhalla kommune. Ledningen vil etter ombygging kunne drives med 420 kV spenning. Søknaden omfatter også utvidelse av Klæbu transformatorstasjon samt ombygging av Verdal, Ogndal og Namsos transformatorstasjoner, og nødvendige omlegginger av eksisterende ledninger ved inn- og eventuelt utføring til nevnte transformatorstasjoner. Denne strekningen utgjør et av flere trinn i spenningsoppgraderingen av sentralnettet i Midt-Norge. Spenningsoppgraderingen og tilhørende anlegg vil berøre Klæbu, Trondheim og Malvik kommuner i Sør-Trøndelag fylke og Stjørdal, Levanger, Verdal, Steinkjer, Namsos og Overhalla kommuner i Nord-Trøndelag fylke. Statnett har i 2008/2009 søkt konsesjon for en ny 420 kV-ledning fra Namsos transformatorstasjon til Storheia i Åfjord kommune. Videreføring fra Storheia via Snillfjord til Orkdal eventuelt Trollheim i Surnadal kommune ble konsesjonssøkt i mai 2010. -

The Pilgrim Bracelet

«In the footsteps of S.t Olav» The short story of the Viking King St Olav 995 Olav Haraldsson was born The Pilgrim bracelet 1014 baptized in Rouen, France 1015/1016 elected king of Norway and introduced Christian law Designed and handmade by craftsmen along S:t Olavsleden in Sweden and Norway 1028 fl ed to Russia because of internal rebellion in the country 1030 returned by boat from Novgorod, Russia, and disembarked in the harbour of Selånger 1030 The Battle of Stiklestad. King Olav was killed 29.07.1030. 1031 King Olav was declared a martyr and a saint, and his remains were smuggled to Trondheim. The relics were later placed in the Nidaros Cathedral and the pilgrimages to the holy king’s relics started immediately. The Norwegian Saint King retained his status as the most esteemed Nordic Saint throughout the Middle Ages. St. Olav is the Patron Saint of Norway. At the pilgrimage centers along the St. Olav Ways you can experience the history of the last millennium history through exhibitions and guided tours. In the Pilgrim pod, you will meet researchers who can tell you more about vikings, saints and medieval pilgrims. Also, do not miss walking in the footsteps of St. Olav through a countryside rich in culture and beautiful woodland and pastoral sceneries. More information can be found at stolavsleden.com pilgrimutangranser.no Selanger Borgsjö 2 5 The bracelet is cut by hand in rough The S.t Olav’s Crown in silver symbo- leather using traditional techniques and lizes the king’s deed, but is also the symbolizes the continuous path from crown of the Lord he saw as Saviour. -

Sak 3 Årsmelding 2020

Sak 3 Årsmelding 2020 Fylkesårsmøtet 2020 Fylkesårsmøtet ble avholdt lørdag 8. februar 2020 på Dyreparken Hotell. Kvelden før, fredag 7. februar hadde vi et jubileumsarrangement samme sted, i forbindelse med at Senterpartiet var 100 år i 2020. Her var Trygve Slagsvold Vedum og flere andre fra partiledelsen til stede. Sigmund Oksefjell ble tildelt Senterpartiets hedersmerke av partilederen. Det ble vedtatt tre uttalelser fra årsmøtet: • Bygg ytre ringvei • Me treng frivilligsentraler også etter 2020 • Større andel av verdiene må bli igjen der de skapes Sigmund Oksefjell ble tildelt hedersmerket Tillitsvalgte Fylkesstyret Fylkesleder: Margrethe Handeland, Hægebostad 1. nestleder: Oddbjørn Kylland, Lillesand 2. nestleder: Thor Jørgen Tjørhom, Sirdal Studieleder: Kristen Helen Myren, Vegårshei Styremedlem: Mona Hoel, Gjerstad Styremedlem: Caroline Høyland, Kvinesdal Styremedlem: Per Dag Hole, Arendal Styremedlem: Anders Snøløs Topland, Birkenes Styremedlem: Ole Magne Omdal, Kristiansand Styremedlem: Signe Sollien Haugå, Bygland 1. vara: Oddmund Ljosland, Åseral 2. vara: Søren Hodne, Evje og Hornnes 3. vara: Kristin Ljosland, Froland 4. vara: Torhild S. Hægeland, Vennesla 5. vara: Kåre Haugaas, Tvedestrand 6. vara: Arild Viken, Grimstad Fylkesstyrets representant til styret i Senterkvinnene: Signe Sollien Haugå Fylkesstyrets representant til styret i Senterungdommen: Anders Snøløs Topland Fylkeslederne for senterungdommen og senterkvinnene møter også i fylkesstyret. Revisorer: Tore Stalleland og Kristian Øverbø Medlemsutvikling Pr. 31.12.2020 -

LINDESNES KOMMUNE Teknisk Etat

LINDESNES KOMMUNE Teknisk etat SAKSMAPPE: 2008/2656 ARKIVKODE: LØPENR.: SAKSBEHANDLER: Sign. 3899/2011 Svein Haugen UTVALG: DATO: SAKSNR: Teknisk styre 12.04.2011 30/11 Kommunestyret 14.04.2011 18/11 Spangereid sentrum 151/19 til endelig vedtak Vedlegg: 1 Spangereid 151/19 plankart 2 Reguleringsbestemmelser - 06.05.10 3 Fylkesmannen, omgjøring av vedtak som stadfester vedtatt reguleringsplan for Spangereid sentrum 4 Vegvesenet, ingen merknader til endring av reguleringsplan for 151/19, Høllen 5 Fylkesmannen, uttalelse til endring i plankart, Reguleringsplan for Spangereid sentrum, 151/19, 6 Fylkeskommunen, vedr. reguleringsplan for Spangereid sentrum, ny offentlig ettersyn 7 Fylkeskommunen, vedr. forespørsel om innsigelse kan trekkes, Reguleringsplan Spangereid sentrum, 151/19 8 Idland, vedr. merknad til endring av reguleringsplan 9 Kystverket, høringsuttalelse til forslag til reguleringsplan 10 Fylkesmannen, uttalelse til reg. plan vedr. 151/19, Høllen 11 Fylkeskommunen, merknader til reguleringsplan 12 Vegvesenet, uttalelse til reguleringsplan, 151/19, Høllen, Arnar Njerve 13 Johnsen, merknader til reguleringsbestemmelse 14 Idland, Johannessen og Dürendahl, merknader til reguleringsplanen 15 Referat møte med Fylkeskommunen vedr. innsigelse 16 Planbeskrivelse.pdf Bakgrunn: Reguleringsplan for Spangereid sentrum 151/19 m.fl. ble fremmet for kommunestyret for endelig vedtak i møte den 15.10.09, sak 92/09. Ved en feil var ikke hele innsigelsen fra Fylkeskommunen avklart på dette tidspunkt. Det har derfor nå blitt gjort to endringer på plankartet som har vært ute på høring, og saken fremmes nå for nytt vedtak. Vedtaket av 15.10.09 var ikke rettsgyldig i og med at innsigelsen ikke var endelig avklart. Derfor er det slik at det er hele planen som vedtas nå, og det blir mulig å klage på vedtaket på vanlig vis. -

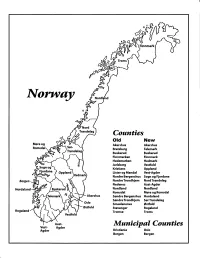

Norway Maps.Pdf

Finnmark lVorwny Trondelag Counties old New Akershus Akershus Bratsberg Telemark Buskerud Buskerud Finnmarken Finnmark Hedemarken Hedmark Jarlsberg Vestfold Kristians Oppland Oppland Lister og Mandal Vest-Agder Nordre Bergenshus Sogn og Fjordane NordreTrondhjem NordTrondelag Nedenes Aust-Agder Nordland Nordland Romsdal Mgre og Romsdal Akershus Sgndre Bergenshus Hordaland SsndreTrondhjem SorTrondelag Oslo Smaalenenes Ostfold Ostfold Stavanger Rogaland Rogaland Tromso Troms Vestfold Aust- Municipal Counties Vest- Agder Agder Kristiania Oslo Bergen Bergen A Feiring ((r Hurdal /\Langset /, \ Alc,ersltus Eidsvoll og Oslo Bjorke \ \\ r- -// Nannestad Heni ,Gi'erdrum Lilliestrom {", {udenes\ ,/\ Aurpkog )Y' ,\ I :' 'lv- '/t:ri \r*r/ t *) I ,I odfltisard l,t Enebakk Nordbv { Frog ) L-[--h il 6- As xrarctaa bak I { ':-\ I Vestby Hvitsten 'ca{a", 'l 4 ,- Holen :\saner Aust-Agder Valle 6rrl-1\ r--- Hylestad l- Austad 7/ Sandes - ,t'r ,'-' aa Gjovdal -.\. '\.-- ! Tovdal ,V-u-/ Vegarshei I *r""i'9^ _t Amli Risor -Ytre ,/ Ssndel Holt vtdestran \ -'ar^/Froland lveland ffi Bergen E- o;l'.t r 'aa*rrra- I t T ]***,,.\ I BYFJORDEN srl ffitt\ --- I 9r Mulen €'r A I t \ t Krohnengen Nordnest Fjellet \ XfC KORSKIRKEN t Nostet "r. I igvono i Leitet I Dokken DOMKIRKEN Dar;sird\ W \ - cyu8npris Lappen LAKSEVAG 'I Uran ,t' \ r-r -,4egry,*T-* \ ilJ]' *.,, Legdene ,rrf\t llruoAs \ o Kirstianborg ,'t? FYLLINGSDALEN {lil};h;h';ltft t)\l/ I t ,a o ff ui Mannasverkl , I t I t /_l-, Fjosanger I ,r-tJ 1r,7" N.fl.nd I r\a ,, , i, I, ,- Buslr,rrud I I N-(f i t\torbo \) l,/ Nes l-t' I J Viker -- l^ -- ---{a - tc')rt"- i Vtre Adal -o-r Uvdal ) Hgnefoss Y':TTS Tryistr-and Sigdal Veggli oJ Rollag ,y Lvnqdal J .--l/Tranbv *\, Frogn6r.tr Flesberg ; \. -

Regionalt Nettverk – Bedrifter Og Virksomheter Som Er Blitt Kontaktet I Arbeidet Med Runde 201 7- 4

Regionalt nettverk – Bedrifter og virksomheter som er blitt kontaktet i arbeidet med runde 201 7- 4 3T produkter AS Boreal Offshore AS Accenture AS Bouvet ASA, Trondheim Adecco Norge AS, Tromsø Bravida Norge AS, Førde Adecco Norge AS, Trondheim Bremnes Seashore AS Adresseavisen AS BRG Advokatfirmaet Schjødt AS Bring International & Offshore, avd. Midt/ Nord Agility Subsea Fabrication BSH husholdningsapparater AS Aibel AS Bulldozer maskinlag entreprenør AS Air Products AS Bunnpriskjeden AS Aker Egersund AS Busengdal transport AS Aktiv365 Bygg og maskin AS Alcoa Norway ANS Båtservice gruppen Alfr. Nesset AS Caiano hotelldrift AS Altus Intervention AS CargoNet AS A- møbler AS Caverion Norge AS Andritz Hydro Gmbh Caverion Norge AS avd Bodø Apollo reiser Caverion Norge AS, avd Gjøvik Apply Sørco AS Celsa armeringsstål AS Arbor- Hattfjelldal AS CGG Marine (Norway) AS Arendal bryggeri AS City Syd AS Artec Aqua Clarion Hotel Energy/Clarion Hotel Air Asko Rogaland AS Clas Ohlson AS Asko Hedmark AS Constructa entreprenør AS Asplan Viak AS Coop Finnmark SA Atea AS avd Bodø Coop Vest SA Avery Dennison NTP AS Cowi AS Avinor AS Cowi AS, Trondheim Axtech AS Cramo AS Balansen Bodø AS CTM Lyng AS Bardu kommune De Historiske hotell & spisesteder SA Beitostølen Resort AS Det Stavangerske dampskibsselskap AS Bergans fritid AS DNB bank ASA, Stavanger Bergen kino AS DNB næringsmegling AS, Oslo Bergens Tidende AS DNV GL Berget AS Drueklasen AS Berg- Hansen reisebureau Vestfold AS EFD Induction AS Bertel O. Steen Rogaland AS Egersund Group AS Bertelsen & Garpestad