Wolfram Mining and the Christian Co-Operative Movement1 Anna Shnukal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

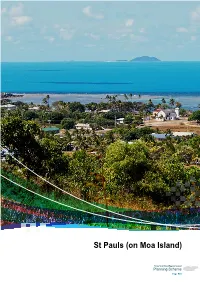

St Pauls (On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.13 St Pauls (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) St Pauls (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 523 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 524 Part 7: Local Plans St Pauls (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu Kubin Moa SStt PPaulsauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 525 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • St Pauls is located on the eastern side of Moa • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Island, which is part of the Torres Strait inner and a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing near western group of islands. St Paul’s nearest Range, now separated by sea. The island neighbour is Kubin, which is located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and south-western side of Moa Island. Approximately is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest 15km from the outskirts of St Pauls. point. • Native flora and fauna that have been identified Population near St Pauls include fawn leaf nosed bat, • According to the most recent census, there were grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, 258 people living in St Pauls as at August 2011, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodactylus however, the population is highly transient and primilus, bare backed fruit bat, torresian tube- this may not be an accurate estimate. -

Part 16 Transport Infrastructure Plan

Figure 7.3 Option D – Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan Masig (Yorke) Island Option D - Rail Line from Cairns to Bamaga Major Roads Moa Island Proposed Railway St Pauls Kubin Waiben (Thursday) Island ° 0 20 40 60 80 100 120 140 Kilometres Seisia Bamaga Ferry and passenger services as per current arrangements. DaymanPoint Shelburne Mapoon Wenlock Weipa Archer River Coen Yarraden Dixie Cooktown Maramie Cairns Normanton File: J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Mapping\ArcGIS\Workspaces\Option D - Rail Line.mxd 29.07.05 Source of Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd Source for Base Map: MapData Sciences Pty Ltd 7.5 Option E – Option A with Additional Improvements This option retains the existing services currently operating in the Torres Strait (as per Option A), however it includes additional improvements to the connections between Horn Island and Thursday Island. Two options have been strategically considered for this connection: Torres Strait Transport Infrastructure Plan - Integrated Strategy Report J:\mmpl\10303705\Engineering\Reports\Transport Infrastructure Plan\Transport Infrastructure Plan - Rev I.doc Revision I November 2006 Page 91 • Improved ferry connections; and • Roll-on roll-of ferry. Improved ferry connections This improvement considers the combined freight and passenger services between Cairns, Bamaga and Thursday Island, with a connecting ferry service to OSTI communities. Possible improvements could include co-ordinating fares, ticketing and information services, and also improving safety, frequency and the cost of services. Roll-on roll-off ferry A roll-on roll-off operation between Thursday Island and Horn Island would provide significant benefits in moving people, cargo, and vehicles between the islands. -

Cultural Heritage Series

VOLUME 4 PART 2 MEMOIRS OF THE QUEENSLAND MUSEUM CULTURAL HERITAGE SERIES 17 OCTOBER 2008 © The State of Queensland (Queensland Museum) 2008 PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone 06 7 3840 7555 Fax 06 7 3846 1226 Email [email protected] Website www.qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the Editor in Chief. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed at the Queensland Museum web site A Queensland Government Project Typeset at the Queensland Museum CHAPTER 4 HISTORICAL MUA ANNA SHNUKAL Shnukal, A. 2008 10 17: Historical Mua. Memoirs of the Queensland Museum, Cultural Heritage Series 4(2): 61-205. Brisbane. ISSN 1440-4788. As a consequence of their different origins, populations, legal status, administrations and rates of growth, the post-contact western and eastern Muan communities followed different historical trajectories. This chapter traces the history of Mua, linking events with the family connections which always existed but were down-played until the second half of the 20th century. There are four sections, each relating to a different period of Mua’s history. Each is historically contextualised and contains discussions on economy, administration, infrastructure, health, religion, education and population. Totalai, Dabu, Poid, Kubin, St Paul’s community, Port Lihou, church missions, Pacific Islanders, education, health, Torres Strait history, Mua (Banks Island). -

Torres Strait Islanders: a New Deal

The Parliament of the Commonwealth of Australia TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS: A NEW DEAL A REPORT ON GREATER AUTONOMY FOR TORRES STRAIT ISLANDERS House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal & Torres Strait Islander Affairs August 1997 Canberra Commonwealth of Australia 1997 ISBN This document was produced from camera-ready copy prepared by the House of Representatives Standing Committee on Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Affairs and printed by AGPS Canberra. The cover was produced in the AGPS design studios. The graphic on the cover was developed from a photograph taken on Yorke/Masig Island during the Committee's visit in October 1996. CONTENTS FOREWORD ix TERMS OF REFERENCE xii MEMBERSHIP OF THE COMMITTEE xiii GLOSSARY xiv SUMMARY AND RECOMMENDATIONS xv CHAPTER 1 – INTRODUCTION REFERRAL TO COMMITTEE.......................................................................................................................................1 CONDUCT OF THE INQUIRY ......................................................................................................................................1 SCOPE OF THE REPORT.............................................................................................................................................2 PRELIMINARY OBSERVATIONS .................................................................................................................................3 Commonwealth-State Cooperation ....................................................................................................................3 -

Badu Land and Sea Profile

Badu Land and Sea Profile RANGER GROUP Rangers 2015 MANAGEMENT PRIORITIES LAND • Native plants and animals • Burning• Land patrol • Weeds • Native nursery • Revegetation • Coastal management (beach patrol) OVERVIEW • Uninhabited island management Traditional island name Badu SEA • Crocodiles Western name Mulgrave • Turtle and dugong • Marine debris Western Islands Cluster Maluilgal Nation • Sea patrol • Seagrass Monitoring Local government TSIRC & TSC Registered Native Title Mura Badulgal (TSI) PEOPLE • Traditional ecological knowledge Body Corporate (RNTBC) Corporation RNTBC • Traditional and cultural sites • Community involvement Land type Continental Island • Visitor management Air distance from • Research support 49 Thursday Island (km) Area (ha) 10222 KEY VALUES Indicative max length (km) 11 CLIMATE CHANGE RISK Indicative max breadth (km) 13 Vulnerability to sea level rise (+1.0m) Very Low Max elevation (m) 190 Sea level rise response options Very High Healthy sea Marine water Coral reefs Seagrass Dugong Marine turtles Coastline length (km) 49 ecosystems quality meadows Population 783 (2011 ABS Census) Area of island zoned 162 development (ha) Subsistence Healthy land Sustainable Coasts Mangroves Coastal birds fishing ecosystems human settlements and beaches and wetlands Area of disturbed / 213 (2.1%) / undisturbed vegetation (ha/%) 10009 (97.9%) Supporting the Land and Sea Management Strategy for Torres Strait COMMUNITY OVERVIEW FUTURE SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES RECENT ACHIEVEMENTS Badu is a large (10,222ha) continental island in the The Badu community is highly reliant on air transport, Recent land and sea management achievements include: Near Western Cluster of the Torres Strait about diesel powered electricity generation and barge transport of supplies and materials to and from the community. 49km north of Thursday Island (Waiben). -

Badu Island ABOUT Thursday Island Cairns

RVTS fact sheet June 2019 Badu Island ABOUT Thursday Island Cairns Townsville BADU ISLAND Queensland QLD Brisbane ABOUT TARGETED RECRUITMENT The Remote Vocational Training Scheme (RVTS) has expanded its traditional workforce retention and training model by recruiting doctors to targeted remote communities with high medical workforce need. The aim is to enhance the attractiveness of rural and remote posts to high quality applicants to provide communities with a well-supported and sustainable GP workforce. The initial pilot of the program in 2018-19 has successfully secured the services of six full-time doctors to six rural and remote communities across Australia. Targeted recruitment positions utilise existing RVTS training positions and infrastructure. The training is fully funded by the Australian Government and is a four-year GP training program delivered by Distance Education and Remote Supervision to Fellowship of the ACRRM and/or RACGP. Location Attractions Housing Education Badu Island is a small island in The Badu Arts Centre With a population of 816, Badu has its own newly built the Torres Strait, 55km north of produces a gorgeous range 91.74% of the population live Child Care Centre for children Thursday Island. Badu is 20km of printmaking, etching, in rental accommodation. aged up from one to four years. in diameter and has direct jewellery, textiles and carving. Badu Island has impressive Tagai College runs a Prep year flights to Horn Isand which Visitors can tour through the infrastructure with a health in its own recently renovated then connect to Cairns. It is facility and watch the wares centre, two grocery stores, a grounds for 4-5 year olds plus dotted with granite hills and being made by Badu Island post office, Centrelink office, a Primary school. -

View Full Report

GREENLAND NORWAY SWEDEN ICELAND RUSSIA FINLAND POLAND GERMANY UKRAINE FRANCE AUSTRIA ROMANIA MONGOLIA KAZAKHSTAN SPAIN ITALY TURKEY SOUTH Elective KOREA GREECE IRAQ AFGANISTAN JAPAN IRAN MORROCO PAKISTAN CHINA EGYPT NEPAL LIBYA SAUDI INDIA GrantARABIA Report THAILAND PHILIPPINES VIETNAM CHAD NIGERIA ETHIOPIA MALAYSIA SRI LANKA INDONESIA Anne-Maree Nielsen PAPUA NEW GUINEA Indigenous Grant Recipient BRAZIL Flinders University PERU TORRES Torres and Cape Hospital and Health Service STRAIT Torres Strait Islands, Australia ISLANDS MADAGASCAR LESOTHO ARGENTINA ThursdaySOUTH AFRICA Island is the commercial centre of AUSTRALIA the Torres Strait Islands and is located 35km north west of Cape York and 800km north of In the helicopter heading Cairns with a population of approximately 2,600. to Coconut Island Queensland Health’s Thursday Island Hospital hosts 26 general/medical beds and 6 maternity beds. It is serviced by local and transient healthcare, administrative and domestic personnel. Medical staff are rostered between the general ward, accident and emergency, obstetrics, health services on the outer islands and the Community Wellness Centre. The Hospital is staffed primarily by general practitioner specialists and this provided me with the chance to see career pathways for practitioners working in remote health environments. This combination of acute care delivery with preventative community healthcare poses an attractive career prospect for me as it requires the use of a diverse range of skills in environments that pose challenges in terms of remoteness. Indigenous healthcare initiatives tailored to life in the Torres Strait and the involvement of allied health and Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander health workers personified the team care approach required to deliver culturally sound healthcare on the islands of Northern Queensland. -

Moa Land and Sea Profile

Mua Land and Sea Profile RANGER GROUP Rangers 2015 MANAGEMENT PRIORITIES LAND • Ecological survey • Feral animals • Weeds • Burning • Community garden OVERVIEW • Native nursery Traditional island name Mua SEA Western name Banks • Turtle and dugong • Crocodiles Western Islands Cluster Maluilgal Nation • Marine debris Local government TSIRC & TSC Registered Native Title Mualgal (TSI) PEOPLE Body Corporate (RNTBC) Corporation RNTBC • Research support • Community involvement Land type Continental Island • Traditional ecological knowledge Air distance from • Traditional and cultural sites 40 Thursday Island (km) Area (ha) 17164 KEY VALUES Indicative max length (km) 17 CLIMATE CHANGE RISK Indicative max breadth (km) 16 Vulnerability to sea level rise (+1.0m) Medium Max elevation (m) 370 Sea level rise response options High Healthy sea Marine water Coral reefs Seagrass Dugong Marine turtles Coastline length (km) 59 ecosystems quality meadows Population 420 (2011 ABS Census) Area of island zoned NA development (ha) Subsistence Healthy land Sustainable Coasts Mangroves Coastal birds fishing ecosystems human settlements and beaches and wetlands Area of disturbed / 424 (2.5%) / undisturbed vegetation (ha/%) 16740 (97.5%) Supporting the Land and Sea Management Strategy for Torres Strait COMMUNITY OVERVIEW FUTURE SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES RECENT ACHIEVEMENTS Mua is a very large (17,164ha) continental island The Mua communities are highly reliant on air transport, Recent land and sea management achievements include: in the Western Islands Cluster of the Torres diesel powered electricity generation and barge transport of supplies and materials to and from the community. Strait about 40km north of Thursday Island. ○ Community-based dugong and turtle management plan in place Renewable energy options will be explored to reduce Mua (population 420) is a granitic island and a ○ Ranger group established and Rangers implementing activities under Working on Country plans carbon emissions and work towards energy independence. -

On Moa Island) - Local Plan Code

7.2.7 Kubin (on Moa Island) - local plan code Part 7: Local Plans Kubin (on Moa Island) Kubin (on Moa Island) Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 371 Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 372 Part 7: Local Plans Kubin (on Moa Island) Papua New Guinea Saibai Ugar Boigu Stephen Island Erub Dauan Darnley Island Masig Yorke Island Iama Mabuyag Yam Island Mer Poruma Murray Island Coconut Island Badu KubinKubin Moa St Pauls Warraber Sue Island Keriri Hammond Island Mainland Australia Mainland Australia Torres Strait Island Regional Council Planning Scheme Page 373 Editor’s Note – Community Snapshot Location Topography and Environment • Kubin is located on the south-western side of • Moa Island, like other islands in the group, is Moa Island, which is part of the Torres Strait a submerged remnant of the Great Dividing inner and near western group of islands. Kubin’s Range now separated by sea. The island nearest neighbour is St Pauls, located on the comprises of largely of rugged, open forest and eastern side of Moa Island, approximately 15km is approximately 17km in diameter at its widest from the outskirts of Kubin. point. • Moa Peak on the north eastern side of the island Population is the highest point in the Torres Strait Regional • According to the most recent census, there were Island Council. 163 people living in Kubin as at August 2011, however, the population is highly transient and • Native flora and fauna that have been identified this may not be an accurate estimate. on Kubin Island include fawn leaf nosed bat, grey goshawk, emerald monitor, little tern, red goshawk, radjah shelduck, lipidodastylus Natural Hazards pumilus, bare backed fruit back, torresian tube- • Coastal hazards, including erosion and storm nosed bat, emoia atrostata, eastern curlew, tide inundation, have an impact on a few low beach stone curlew, coastal sheatail bat. -

Mabuiag Land and Sea Profile

Mabuiag Land and Sea Profile RANGER GROUP Rangers 2015 MANAGEMENT PRIORITIES LAND • Native plants and animals • Land patrol • Feral animals • B urning • Weeds • Coastal management OVERVIEW (beach patrol) • Native Nursery Traditional island name Mabuiag SEA Western name Jervis • Sea patrol • Seagrass Western Islands Cluster Maluilgal Nation • Turtle and dugong • Crocodiles Local government TSIRC & TSC Registered Native Title Goelmulgaw (TSI) PEOPLE • Traditional ecological knowledge Body Corporate (RNTBC) Corporation RNTBC • T raditional and cultural sites (including IPA) Land type Continental Island • Community involvement Air distance from • R esearch support 71 Thursday Island (km) Area (ha) 648 KEY VALUES Indicative max length (km) 4 CLIMATE CHANGE RISK Indicative max breadth (km) 3 Vulnerability to sea level rise (+1.0m) Medium Max elevation (m) 150 Sea level rise response options High Healthy sea Marine water Coral reefs Seagrass Dugong Marine turtles Coastline length (km) 13 ecosystems quality meadows Population 261 (2011 ABS Census) Area of island zoned 63 development (ha) Subsistence Healthy land Sustainable Coasts Mangroves Coastal birds fishing ecosystems human settlements and beaches and wetlands Area of disturbed / 69 (10.6%) / undisturbed vegetation (ha/%) 579 (89.4%) Supporting the Land and Sea Management Strategy for Torres Strait COMMUNITY OVERVIEW FUTURE SUSTAINABILITY INITIATIVES RECENT ACHIEVEMENTS Mabuiag is a small (648ha) continental island The Mabuiag community is highly reliant on air transport, diesel powered electricity generation and barge transport in the Western Islands Cluster of the Torres Recent land and sea management achievements include: of supplies and materials to and from the community. ○ Community-based dugong and turtle management plan in place Strait about 71km north of Thursday Island. -

Boigu Island Are Extensions of the Papua New Guinea Mainland Which Is Clearly Visible from the Islands Northern Coastline2

PROFILE FOR MANAGEMENT OF THE HABITATS AND RELATED ECOLOGICAL AND CULTURAL RESOURCE VALUES OF SAIBAI ISLAND January 2013 Prepared by 3D Environmental for Torres Strait Regional Authority Land & Sea Management Unit Cover image: TSRA (2013) EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Along with the nearby island of Boigu and the granite rock pile that forms Dauan, Saibai forms part of the Northern Island group of the Torres Strait. The island is a remnant of the Fly Platform, with the Papua New Guinea mainland clearly visible and within four kilometres from Saibai’s northern coastline. Located approximately 150 km north of Thursday Island it has an area of 11 211 hectares. The entire island is low lying and swampy, particularly the interior and southern portions. The majority of the island landscape is formed from recent estuarine sediments, with an extensive remnant of a Pleistocene age alluvial plain located on the islands northern coastline and extending into the islands interior where it becomes increasingly dissected by broad drainage swamps. A narrow sliver of indurated ironstone caprock (laterite) is exposed along the islands northern coastline on which Saibai village is situated, and number beach ridges (or strandlines) parallel the islands south-eastern and southern coastline forming low linear rises and supporting littoral rainforest. The island supports a rich and diverse cultural tradition which includes traditional food gardening and plant and animal utilisation. Archeological studies have documented extensive prehistoric relict mound-and-ditch horticultural field systems which extend across 650 hectares of the island together with associated irrigation channels, wells and constructed access routes into the interior of the island for canoes. -

Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J

Memoirs of the Queensland Museum | Culture Volume 8 Part 1 Goemulgaw Lagal: Natural and Cultural Histories of the Island of Mabuyag, Torres Strait. Edited by Ian J. McNiven and Garrick Hitchcock Minister: Annastacia Palaszczuk MP, Premier and Minister for the Arts CEO: Suzanne Miller, BSc(Hons), PhD, FGS, FMinSoc, FAIMM, FGSA , FRSSA Editor in Chief: J.N.A. Hooper, PhD Editors: Ian J. McNiven PhD and Garrick Hitchcock, BA (Hons) PhD(QLD) FLS FRGS Issue Editors: Geraldine Mate, PhD PUBLISHED BY ORDER OF THE BOARD 2015 © Queensland Museum PO Box 3300, South Brisbane 4101, Australia Phone: +61 (0) 7 3840 7555 Fax: +61 (0) 7 3846 1226 Web: qm.qld.gov.au National Library of Australia card number ISSN 1440-4788 VOLUME 8 IS COMPLETE IN 2 PARTS COVER Image on book cover: People tending to a ground oven (umai) at Nayedh, Bau village, Mabuyag, 1921. Photographed by Frank Hurley (National Library of Australia: pic-vn3314129-v). NOTE Papers published in this volume and in all previous volumes of the Memoirs of the Queensland Museum may be reproduced for scientific research, individual study or other educational purposes. Properly acknowledged quotations may be made but queries regarding the republication of any papers should be addressed to the CEO. Copies of the journal can be purchased from the Queensland Museum Shop. A Guide to Authors is displayed on the Queensland Museum website qm.qld.gov.au A Queensland Government Project Design and Layout: Tanya Edbrooke, Queensland Museum Printed by Watson, Ferguson & Company The terrestrial vertebrate fauna of Mabuyag (Mabuiag Island) and adjacent islands, far north Queensland, Australia Justin J.