Vectors and Frames of Reference: Evidence from Seri and Yucatec

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Reduction of Seri Indian Range and Residence in the State of Sonora, Mexico (1563-Present)

The reduction of Seri Indian range and residence in the state of Sonora, Mexico (1563-present) Item Type text; Thesis-Reproduction (electronic) Authors Bahre, Conrad J. Publisher The University of Arizona. Rights Copyright © is held by the author. Digital access to this material is made possible by the University Libraries, University of Arizona. Further transmission, reproduction or presentation (such as public display or performance) of protected items is prohibited except with permission of the author. Download date 24/09/2021 15:06:07 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/10150/551967 THE REDUCTION OF SERI INDIAN RANGE AND RESIDENCE IN THE STATE OF SONORA, MEXICO (1536-PRESENT) by Conrad Joseph Bahre A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the DEPARTMENT OF GEOGRAPHY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF ARTS In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 1 9 6 7 STATEMENT BY AUTHOR This thesis has been submitted in partial fulfill ment of requirements for an advanced degree at The University of Arizona and is deposited in the University Library to be made available to borrowers under rules of the Library. Brief quotations from this thesis are allowable without special permission, provided that accurate acknowl edgment of source is made. Requests for permission for extended quotation from or reproduction of this manuscript in whole or in part may be granted by the head of the major department or the Dean of the Graduate College when in his judgment the proposed use of the material is in the inter ests of scholarship. In all other instances, however, permission must be obtained from the author. -

Recent Investigations on Quaternary Geology of the Coast of Central Sonora, Mexico

137 RECENT INVESTIGATIONS ON QUATERNARY GEOLOGY OF THE COAST OF CENTRAL SONORA, MEXICO Luc ORTLIEB Mission de l'Office de la Recherche Scientifique et Technique Outre-Mer au Mexique, & Instituto de Geolog!a, Universidad Nacional AutOnoma de Mexico, Apdo. Postal 1159, Hermosillo, Sonora, Mexico. INTRODUCTION Between 1965 and 1980, Quaternary deposits of the coast of Sonora, between Puerto Lobos (30 015') and Guaymas (28°N) have been investigated from different points of view. This new interest in the recent evolution of this area, follows the important geologic, geophysical and oceanographic research accomplished in the Gulf of California around the mid-century. The aim of this paper is to briefly present some aspects of these recent investigations and give a general idea of the state of knowledge in the field of Quaternary geology in the western Sonora coast. On- going research works will also be mentioned. With the exception of a few PhD dissertations, and other works, from U. s. scientists, a large part of the recent progresses were completed through a Franco-Mexican cooperative program (between O. R. S. T. O. M. and Instituto de Geolog!a , U. N. A. M.) which began in 1974 ( the publications related to this program, generally were written in Spanish, or in French; and not in English) • REGIONAL GEOLOGY AND RECONNAISSANCE MAPPING In the early sixties, the geology of coastal Sonora was so poorly studied that Allison (1964) could write: "So little is known of rocks younger than Cre taceous that conclusions concerning the late geological history of land areas bordering the eastern side of the Gulf of California are hardly meaningful". -

Community Based Conservation of the Callo Hacha Fishery by the Comcaac

COMMUNITY-BASED CONSERVATION OF THE CALLO DEHACHA FISHERY BY THE COMCAAC INDIANS, SONORA, MEXICO by Xavier Basurto Guillermo A Thesis Submitted to the Faculty of the SCHOOL OF RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE WITH A MAJOR IN RENEWABLE NATURAL RESOURCES STUDIES In the Graduate College THE UNIVERSITY OF ARIZONA 2002 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS This research was possible due to the financial support from the Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnologia (CONACyT), the Inter-American Foundation (IAF), and the Wallace Research Foundation. Essential as well, was the consent to conduct this research granted by the Seri Traditional Government headed by Moises Mendes. The Lopez Morales and Valenzuela families, Hudson Weaver, Tad Pfister, and the Rodriguez family, Duncan Duke, Adriana Cardenas, and Andy Small, generously provided in-kind support during fieldwork seasons. I am especially thankful to the staff of Comunidad y Biodiversidad A.C. Saul Serrano shared with me unpublished callo de hacha data. Enrique Arizmendi, Michael Dadswell and Duncan Bates enriched me with useful lessons on oceanography, marine ecology, and perseverance. Stephen Marlett went out of his way to review the Seri toponymy. Adriana, Maria Eugenia and Alejandro Basurto searched libraries in Mexico City to send me literature I could not find here. A todos gracias. For Luis Bourillon, Jorge Torre, Marisol Tordesillas, and Hudson Weaver my recognition for your professional commitment and patience. This work is part of a joint journey that started in the hot summer of 1998. Many thanks to Jen Pettis, Paquita Hoeck, Curtis Andrews (Ponch), and Rocio Covarrubias, for excellent assistance in the field. -

SERI LANDSCAPE CLASSIFICATION and SPATIAL REFERENCE By

SERI LANDSCAPE CLASSIFICATION AND SPATIAL REFERENCE by Carolyn O’Meara June 1, 2010 A dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of the University at Buffalo, State University of New York in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Department of Linguistics UMI Number: 3407934 All rights reserved INFORMATION TO ALL USERS The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. In the unlikely event that the author did not send a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. UMI 3407934 Copyright 2010 by ProQuest LLC. All rights reserved. This edition of the work is protected against unauthorized copying under Title 17, United States Code. ProQuest LLC 789 East Eisenhower Parkway P.O. Box 1346 Ann Arbor, MI 48106-1346 Acknowledgements This dissertation could not have been written without the support and assistance of many people, some of whom I would like to acknowledge here. First of all, this dissertation could not have been completed without the ever- present support of my advisor, Dr. Jürgen Bohnemeyer. He began meeting with me in my first year of graduate school and from the beginning he helped me develop my skills in conducting linguistic fieldwork, developing research questions and developing solutions to such questions, as well as preparing presentations and, of course, writing. Vielen Dank Jürgen! Dr. David Mark has also been instrumental in the direction of my research. His work in ethnophysiography inspired me to go to the field and conduct research similar to his, albeit with a bit more of a linguistic focus. -

How Locally Designed Access and Use Controls Can Prevent the Tragedy of the Commons in a Mexican Small-Scale Fishing Community

Society and Natural Resources ISSN: 0894-1920 (Print) 1521-0723 (Online) Journal homepage: http://www.tandfonline.com/loi/usnr20 How Locally Designed Access and Use Controls Can Prevent the Tragedy of the Commons in a Mexican Small-Scale Fishing Community Xavier Basurto To cite this article: Xavier Basurto (2005) How Locally Designed Access and Use Controls Can Prevent the Tragedy of the Commons in a Mexican Small-Scale Fishing Community, Society and Natural Resources, 18:7, 643-659, DOI: 10.1080/08941920590959631 To link to this article: https://doi.org/10.1080/08941920590959631 Published online: 01 Sep 2006. Submit your article to this journal Article views: 652 View related articles Citing articles: 54 View citing articles Full Terms & Conditions of access and use can be found at http://www.tandfonline.com/action/journalInformation?journalCode=usnr20 Society and Natural Resources, 18:643–659 Copyright # 2005 Taylor & Francis Inc. ISSN: 0894-1920 print/1521-0723 online DOI: 10.1080/08941920590959631 How Locally Designed Access and Use Controls Can Prevent the Tragedy of the Commons in a Mexican Small-Scale Fishing Community XAVIER BASURTO School of Public Administration and Policy, University of Arizona, Arizona, USA, and Comunidad y Biodiversidad AC, Sonora, Mexico The Seri people, a self-governed community of small-scale fishermen in the Gulf of California, Mexico, have ownership rights to fishing grounds where they harvest highly valuable commercial species of bivalves. Outsiders are eager to gain access, and the community has devised a set of rules to allow them in. Because Seri govern- ment officials keep all the economic benefits generated from granting this access for themselves, community members create alternative entry mechanisms to divert those benefits to themselves. -

A Bibliography for the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California)

A Bibliography for the Sea of Cortez (Gulf of California) Compiled by R. C. Brusca Vers. 27 September 2021 NOTE: This document is updated on an ongoing basis (see date stamp above) While not complete, this list will provide a good entry into the literature. With a few notable exceptions, chapters in edited volumes are not cited when the volume itself is cited. Some older (pre-2000) species-level taxonomic publications are generally not included unless they have broader biological implications, although systematic revisions often are included. Non-peer- reviewed magazines and government reports are generally not cited, unless the veracity of the data are publically verifiable or especially timely (e.g., the vaquita porpoise situation in the Upper Gulf). The Mexican “scientific literature” is high in non-refereed work from various agencies and universities (e.g., CONACyT, SEMARNAT, CONABIO, CICESE, UABC, UABCS) and nonprofit organizations (e.g., CEDO, Pronatura) and this work is generally not cited herein. Some journals are of low quality and papers from those should be viewed with caution (e.g., Frontera Norte). Academic theses and unrefereed abstracts from conference proceedings generally also are not cited (although a few key ones are). Numerous key terrestrial/freshwater/botanical publications are included in this list when they are of interest to coastal investigators (e.g., the Pinacates, the Colorado River Delta, Baja California, coastal desert streams and springs, etc) or deal with Gulf/Baja/Northwest Mexico geological and biogeographical history. Similarly, some important papers on Arizona and California geology, hydrology, etc. are included when they have direct relevance to the Gulf of California, as are some key papers from the Temperate East Pacific that treat the biology of species also occurring in the Sea of Cortez. -

Mapping and GIS Analysis of Place Names Along the Sonora Coast in Mexico

Mapping and GIS analysis of place names along the Sonora coast in Mexico GEO 511 Master’s Thesis Author Henzi Martina 11-922-234 Supervised by Dr. Flurina Wartmann Prof. Dr. Ross S. Purves Prof. Dr. Carolyn O’Meara (Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México, [email protected]) Faculty representative Prof. Dr. Ross S. Purves 21.04.17 Department of Geography, University of Zurich Acknowledgments Acknowledgments I would like to take the opportunity to thank several people for their input, support and for making this master project possible. It was a great scientific and personal experience and I am happy to say that I learned a lot during the last year. • I would like to thank Dr. Flurina Wartmann and Prof. Dr. Ross S. Purves for their valuable advice and support in achieving this thesis. • A special thank goes to Prof. Dr. Carolyn O’Meara for her engagement: She shared her knowledge and research area, the Seri community, with me and supported me essentially during field work with the logistics, helpful advice and encouragement. • I would also like to acknowledge the provided shapefiles with archaeological sites on the Sonora coast by Dr. César Villalobos. • Hax haa tiipe, comcaac! Thank you for welcoming me in your community and for sharing your personal experiences and knowledge. I would like to thank Ana Teresa Hoeffer Felix, Berta Estrella Romero, Héctor Perales Torres, Hilda Morales Astorga, Manuel Monroy, María Luisa Astorga, René Montaño Herrera, Rogelio Montaño Herrera, Samuel Monroy Morales, Saúl Gabriel Molina, Vilma Irasema Morales Astorga and others for participating in this project. • Last, but not less important, I would like to thank my family, partner and friends for supporting me. -

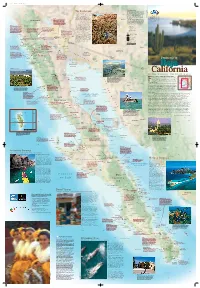

Baja California Map Guide

Baja map side 1/15/08 9:44 AM Page 1 S D N What is geotourism all about? N I A K L P S According to National Geographic, geotourism “sustains I O H A E N or enhances the geographical character of a place—its I The Borderland E L L A H environment, culture, aesthetics, heritage, and the well- T P A L C I N T E R M I N G L I N G F L A V O R S U N D E R G L O R I O U S L I G H T A A being of its residents.” Geotravelers, then, are people who R T 117° 116° 115° 112° N To live along the Baja California-U.S. like that idea, who enjoy authentic sense of place and A S care about maintaining it. They find that relaxing and N border is to be part of a shared history O T having fun gets better—provides a richer experence— E —Old West towns transformed into S geo.tour.ism (n): Tourism N when they get involved in the place and learn about U neon cities mixed with extreme cli- S that sustains or enhances the Mexicali mates and disparate cultures. You can what goes on there. geographical character of a Grab a seat at the El Acueducto bar in feel this sensation in Mexicali’s Chinese BPhoenix Geotravelers soak up local culture, hire local guides, place—its environment, culture, Hotel Lucerna and ask for the world restaurants where sweet and sour Asian buy local foods, protect the environment, and take pride aesthetics, heritage, and the CALIFORNIA famous tomato juice and clam juice in discovering and observing local customs. -

Ethnomedicinal Research Has Historically Focusses on Botanical Products, Ignoring, by and at Large, the Records on Animal-Based Medicine

ONE KNOWLEDGE, TWO CONDUITS: THE SOCIAL, DEMOGRAPHIC, AND TOXICOLOGICAL FACTORS THAT GOVERN SERI ETHNOMEDICINE. by NEMER EDUARDO NARCHI NARCHI (Under the direction of Brent Berlin) ABSTRACT ! !Ethnomedicinal research has historically focusses on botanical products, ignoring, by and at large, the records on animal-based medicine. Whenever non- botanical -e.g. animal-based- remedies appear on indigenous pharmacopoeias, these are taken with little interest and are explained as de facto - i.e. “They occur because they occur-” This lack of interest impedes ethnobiologists to develop further investigations or theoretical afterthoughts that would enable to articulate ethnomedicinal systems as holistic ecological adaptations. !Among non-botanical medicines, those from marine origins hardly receive any mention. This dissertation describes how do botanical and marine medicines relate within an ethnomedicinal knowledge system. !In this research, I focussed on Seri ethnomedicine. The Seri are an indigenous group of hunter-gatherers located in the mainland portion of the Central Gulf Region in Sonora, Mexico. Seri posses a pragmatic ethnomedicinal system which provides a rich case for this examination as there is little room for cultural features to restrict the flow of ethnomedicinal knowledge between informants. !During a one year long survey in a Seri village, I used participant observation, focus-group interviews, and an ethnomedicinal knowledge test to interview 67 Seri informants. By presenting the individuals with an ethnomedicinal knowledge test, I evaluated each informant"s proficiency in ethnomedicinal knowledge and gathered information on the organoleptic strategies used in the selection of medicinal organisms. I then determined the toxicological profiles of marine and terrestrial medicines. !Seri marine and terrestrial medicines are part of one single pharmacopoeia. -

UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations

UCLA UCLA Electronic Theses and Dissertations Title Artistic Expression in the Crossroads of Los Angeles: Adornment, Beautification, and Guerilla Jewelry Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7bv3h40m Author Montano, Damien P. Publication Date 2017 Peer reviewed|Thesis/dissertation eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Indigenous Artistic Expression in the Crossroads of Los Angeles: Adornment, Beautification, and Guerrilla Jewelry A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of the Arts in American Indian Studies by Damien P. Montano 2017 ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS Indigenous Artistic Expression in the Crossroads of Los Angeles: Adornment, Beautification, and Guerrilla Jewelry by Damien P. Montano Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California, Los Angeles, 2017 Professor Mishuana R. Goeman, Chair The intended purpose of my thesis is to, initially, explore the transformation of the cultural functions of traditional Native American artwork and jewelry occurring today. In addition, I will define the concept “Guerilla Jewelry” in the particular context which I have applied the term by presenting existing figurative and literal representations relevant to my work. Furthermost, I will present an argument distinguishing the correlation between Indigenous Art and Guerrilla Art. ii The thesis of Damien P. Montano is approved Benjamin Madley Michelle Erai Mishuana R. Goeman, Committee Chair University of -

Commercial Diving and the Callo De Hacha Fishery in Seri Territory

Commercial Diving and the Callo de Hacha Fishery in Seri Territory XAVIER BASURTO This paper examines commercial diving in Seri territory, from its early stages to contemporary practices. Commercial diving in Seriland is not only a story of marine-resource exploitation; it is also a tale of close interaction between two historically antagonistic sociocultural groups. From the times of the pearl hunters (1720–1733) to the present callo de hacha (scallop) fishery, Seri and Mexican mestizo fishermen have repeatedly conflicted and cooperated in their efforts to harvest marine bivalves. Grasping the nature of such interactions is crucial for under- standing how the fishery began, how it has changed over time, and how it is organized today. The Seri, or Comcaác, are a group of seafaring hunter-gatherers who, before becoming sedentary, were organized in seminomadic bands (Moser 1999; Sheridan 1999). There is evidence that their coastal territory covered an extensive portion of the coastal Sonoran Desert, spanning from north of Puerto Lobos to as far south as Guaymas, and that they had permanent populations on Tiburón and San Estéban Islands (Moser 1999; Bowen 2000). After European arrival, the Seri faced relentless wars of extermination led by the Spaniards and later continued by Mexican ranchers, with often ferocious battles lasting into the early twentieth century (Spicer 1962; Sheridan 1999; Bourillón 2002). Today, the remaining Seri live in the two permanent villages of Punta Chueca and El Desemboque. According to national census data (INEGI 2000), the total Seri population is around 420 people. Because the Seri are one of the smallest ethnic groups in Mexico, in the 1970s the federal govern- ment granted them legal property rights to a portion of their historic coastal territory. -

Commercial Diving and the Callo De Hacha Fishery in Seri Territory

Commercial Diving and the Callo de Hacha Fishery in Seri Territory XAVIER BASURTO This paper examines commercial diving in Seri territory, from its early stages to contemporary practices. Commercial diving in Seriland is not only a story of marine-resource exploitation; it is also a tale of close interaction between two historically antagonistic sociocultural groups. From the times of the pearl hunters (1720–1733) to the present callo de hacha (scallop) fishery, Seri and Mexican mestizo fishermen have repeatedly conflicted and cooperated in their efforts to harvest marine bivalves. Grasping the nature of such interactions is crucial for under- standing how the fishery began, how it has changed over time, and how it is organized today. The Seri, or Comcaác, are a group of seafaring hunter-gatherers who, before becoming sedentary, were organized in seminomadic bands (Moser 1999; Sheridan 1999). There is evidence that their coastal territory covered an extensive portion of the coastal Sonoran Desert, spanning from north of Puerto Lobos to as far south as Guaymas, and that they had permanent populations on Tiburón and San Estéban Islands (Moser 1999; Bowen 2000). After European arrival, the Seri faced relentless wars of extermination led by the Spaniards and later continued by Mexican ranchers, with often ferocious battles lasting into the early twentieth century (Spicer 1962; Sheridan 1999; Bourillón 2002). Today, the remaining Seri live in the two permanent villages of Punta Chueca and El Desemboque. According to national census data (INEGI 2000), the total Seri population is around 420 people. Because the Seri are one of the smallest ethnic groups in Mexico, in the 1970s the federal govern- ment granted them legal property rights to a portion of their historic coastal territory.