Variation in Ethnonym-Based Names of Clothing Items in Russian Dialects: a Cultural and Sociolinguistic Study

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

RG International

+91-8037436755 RG International https://www.indiamart.com/rg-international-delhi/ We “RG International” are Manufacturer and Wholesaler of the best quality Mens Neck Tie, Bow Tie, Tie Clip. Buy Now: https://www.ollera.in/ About Us Established in the 2017 year at Delhi, we “RG International” are Sole Proprietorship Firm and acknowledged among the noteworthy Manufacturer and Wholesaler of the best quality Mens Tie, Tie Clip, Designer Party Wear Tie Cufflinks And Handkerchief Sets, Black Satin Neck Tie Men, Mens Black Bow Tie and Blue Necktie And Cufflinks Sets. Our products are high in demand due to their premium quality and affordable prices. Furthermore, we ensure to timely deliver these products to our clients, through this we have gained a huge clients base in the market. For more information, please visit https://www.indiamart.com/rg-international-delhi/profile.html TIE CUFFLINK AND HANDKERCHIEF SETS O u r P r o d u c t s Ollera Premium Necktie Set In Checkered Tie Cufflinks And Wooden Box Handkerchief Sets Tie Cufflink And Handkerchief Tie Cufflink And Handkerchief Sets Sets NECKTIE AND CUFFLINKS SETS O u r P r o d u c t s Designer Wedding Necktie Embroidered Necktie And And Cufflinks Sets Cufflinks Sets Silk Necktie And Cufflinks Fashion Necktie And Cufflinks Sets Sets MENS TIE O u r P r o d u c t s Mens Printed Silk Tie Mens Formal Tie Mens Corporate Ties Mens Printed Tie BOW TIE AND CUFFLINK SET O u r P r o d u c t s Mens Plain Bow Tie Mens Dotted Bow Tie Mens Plain Bow Tie And Mens Red Bow Tie Cufflink Set COVID HANDS FREE DOOR -

Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines

Chair of Urban Studies and Social Research Faculty of Architecture and Urbanism Bauhaus-University Weimar Fashion in the City and The City in Fashion: Urban Representation in Fashion Magazines Doctoral dissertation presented in fulfillment of the requirement for the degree of Doctor philosophiae (Dr. phil.) Maria Skivko 10.03.1986 Supervising committee: First Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Frank Eckardt, Bauhaus-University, Weimar Second Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Stephan Sonnenburg, Karlshochschule International University, Karlsruhe Thesis Defence: 22.01.2018 Contents Acknowledgements ................................................................................................................................. 5 Thesis Introduction .................................................................................................................................. 6 Part I. Conceptual Approach for Studying Fashion and City: Theoretical Framework ........................ 16 Chapter 1. Fashion in the city ................................................................................................................ 16 Introduction ....................................................................................................................................... 16 1.1. Fashion concepts in the perspective ........................................................................................... 18 1.1.1. Imitation and differentiation ................................................................................................ 18 1.1.2. Identity -

Clothing Terms from Around the World

Clothing terms from around the world A Afghan a blanket or shawl of coloured wool knitted or crocheted in strips or squares. Aglet or aiglet is the little plastic or metal cladding on the end of shoelaces that keeps the twine from unravelling. The word comes from the Latin word acus which means needle. In times past, aglets were usually made of metal though some were glass or stone. aiguillette aglet; specifically, a shoulder cord worn by designated military aides. A-line skirt a skirt with panels fitted at the waist and flaring out into a triangular shape. This skirt suits most body types. amice amice a liturgical vestment made of an oblong piece of cloth usually of white linen and worn about the neck and shoulders and partly under the alb. (By the way, if you do not know what an "alb" is, you can find it in this glossary...) alb a full-length white linen ecclesiastical vestment with long sleeves that is gathered at the waist with a cincture aloha shirt Hawaiian shirt angrakha a long robe with an asymmetrical opening in the chest area reaching down to the knees worn by males in India anklet a short sock reaching slightly above the ankle anorak parka anorak apron apron a garment of cloth, plastic, or leather tied around the waist and used to protect clothing or adorn a costume arctic a rubber overshoe reaching to the ankle or above armband a band usually worn around the upper part of a sleeve for identification or in mourning armlet a band, as of cloth or metal, worn around the upper arm armour defensive covering for the body, generally made of metal, used in combat. -

TARGET CORPORATION Hardlines Production Test Report V28 BUREAU VERITAS

TARGET CORPORATION Hardlines Production Test Report V28 BUREAU VERITAS Report Number: (8512)045-0118 Page 1 of78 02/24/2012 A llu n·:o1 1 , .,., il :l' Slll' ll l hl' ll Cu., l.ttl I L hf' •l i 1' ' ' ~" ·' 1 1_., ,j · q .. ,.·,. .. J,_,h:·.•· -• II (,.,! .• ,.J j,..• •· " 1\ ,,•, ,J •: T' ·; •l •'O: nlt·· ,,•111-". ,,1"' ' ·,• ' '!:'. ~ , .. , ,.,._ ,\~1,- -•• \ " 1•1-• 1~. · .. , ~.!: ..:, .. · ,,,· h '!•? .\ •l: (••j• .. •'llq ,' . • -, ,o[tf•/'l. j':l!•t l• f·•l· :•·!1_, , ,,._,;, ... ~!I . lllod : Ll, ~ l i u l i tl .1 lnd1hl1 i:o i Bui ltl ing, ,, :,;~ l'l l·\' " ''' •. r I •.• II ! .• ,.: •• r-'" .. ;, .l u:,:,. ,, ·l, , , I ·.-··;' r .~t 1'''111. ·•:• I! l•r·•tl • ,l\ ,,,,,,, , .; ,, ( ' •: •• ,' : . \\ ·1, -li lt b >nt· tJr llf•nt.fw:diug lurlu''' ial l':o•l.. h ·j•.d I•• tl .. h t • • /-.·: 1.. ,,•. • I I ,, · l i•' l• • · ., • ,1 :o•:\lo • tl, • r.:1• oJ I ' I : I ~t ·u,· l •; h t ·• ' ' H•' PI t1.., •1 ·l' \ I ·~ ~,._• . ,, _ ~ !,!.•' ... · 11! t ! • 1 •: f; ,.- q · -.: lt t h•: • • ,.'.. \ . ·I ·'.., 11•1 .• -..\ , - ''I ' t ; . J. ' ·, tl j • I I L ' "•: ,: • •:• I~ ' I .• ,:, 1 .:,.J I J Xiii 'f " '' 11 . N ~1 h h : 111 Di,tt icl. Sh-·nl h,· ll. 1~.;~•: 1 'll ,,o'JP!I; 1-..•'•h•: •,,1 1 ,• :-tll 1 1 1 -~ 1 ~• ''•II ,,,,fl •--1· -•! lj o·,jl • ' •:/H~' • lf- tl )l't j ,P\ I \ :o 1l • ) tJi o •\ \' ( 'IJ J~.• ( i u :o n gdo n ~ . P.ICC. I , f. l ,l ' • , ,( " 1 "' t •l t 1• ''I ·11 I•• !.· :d) • • ••I ,. -

Updated Allison Reed Lot Listing

ALLISON REED UPDATED LOT LISTING Allison Reed Lot Listing (subject to change) Lot# Quantity Description 1 21 Cases of 2"x 2" cardboard boxes 2 1 Drafting table - metal 3 9 Cases of assorted necklace boxes 4 1 Lot: 14 cases of assorted jewelry boxes 5 10 Cases of jewelry box inserts 6 1 Lot: Misc. barcelet box inserts 7 1 Lot: 10 cases of assorted earring cards 8 1 Lot: 12 cases of assorted earring/necklace cards 9 36 Cases of earring cards 10 5 Cases of ring boxes 11 5 Cases of cufflink boxes (black) 12 6 Cases of cufflink boxes (gray) 13 11 Cases of ring boxes 14 15 Cases of ring boxes (clear) 15 1 Lot: 7 cases of assorted ring/cufflink boxes 16 19 Cases of cufflink boxes (gray) 17 9 Cases of cufflink boxes (beige) 18 1 Lot: 4 cases of assorted velour jewelry boxes 19 7 Cases of wrist watch boxes 20 7 Cases of ring boxes 21 34 Cases of earring boxes (black) 22 5 Cases of ring boxes 23 1 Flats of costume jewelry white metal production models 24 1 Five foot work bench 25 15 Sections of metal shelving 26 1 Lot: Two large electric motors (condition unknown) !1 27 1 Lot: Two large electric motors (condition unknown) 28 1 Lot: Misc. electric motors, electric switches, machine fan belts 29 1 Lot: Electric motors and parts 30 6 Sections of metal shelving - 3'L x 1' W 31 15 Cases of seasonal jewelry boxes - snowflake - 4"x4"x1" 32 17 Cases of seasonal jewelry boxes - snowflake - 4"x4"x1" 33 22 Cases of seasonal jewelry boxes - snowflake - 4"x4"x1" 34 12 Cases of ring boxes 35 13 Cases of assorted ring boxes 36 14 Cases of necklace boxes w/sleeve 37 5 Cases of assorted ring/necklace boxes 38 6 Sections of metal shelving - 3'L x 1' W 39 1 Lot: Aprox. -

Aikaterini Despoina Mavromoustakaki

ii Creative, entrepreneurial, and branding strategy for a novel jewellery line Aikaterini Despoina Mavromoustakaki INTERNATIONAL HELLENIC UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF ECONOMICS, BUSINESS ADMINISTRATION & LEGAL STUDIES A thesis submitted for the degree of Master of Science (MSc) in Strategic Product Design March 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece iii iv Student Name: Aikaterini Despoina Mavromoustakaki SID: 1106160018 Supervisor: Prof. Ioanna Symeonidou This dissertation was written as part of the MSc in Strategic Product Design at the International Hellenic University. I hereby declare that the work submitted is mine and that where I have made use of another’s work, I have attributed the sources according to the Regulations set in the Student’s Handbook. March 2018, Aikaterini Despoina Mavromoustakaki, Cover Design, by Aikaterini Despoina Mavromoustakaki No part of this dissertation may be copied, reproduced or transmitted without the author's prior permission. March 2018 Thessaloniki – Greece v vi Abstract Jewellery is considered to be the epitome of beauty and luster. Thousands of years ago, man was creating unique jewel pieces, on the basis of ornamentation of the body, demonstration of social status and expression of socio-economic and cultural aspects of their life. Forms depicting nature, scarce or everyday materials, processing methods and fabrication techniques of the past, are still in practice today, and if combined with contemporary jewellery practices, the results present opportunities for design innovation. Technology-enhanced jewellery is entering the market, gaining market share and positioning themselves next to widely-known branded enterprises. The Millennials seem to respond positively to this technological call, showing interest towards augmented jewellery pieces that offer enhanced features when compared to mere adornments. -

A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker

LIBRARY v A Dictionary of Men's Wear Works by Mr Baker A Dictionary of Men's Wear (This present book) Cloth $2.50, Half Morocco $3.50 A Dictionary of Engraving A handy manual for those who buy or print pictures and printing plates made by the modern processes. Small, handy volume, uncut, illustrated, decorated boards, 75c A Dictionary of Advertising In preparation A Dictionary of Men's Wear Embracing all the terms (so far as could be gathered) used in the men's wear trades expressiv of raw and =; finisht products and of various stages and items of production; selling terms; trade and popular slang and cant terms; and many other things curious, pertinent and impertinent; with an appendix con- taining sundry useful tables; the uniforms of "ancient and honorable" independent military companies of the U. S.; charts of correct dress, livery, and so forth. By William Henry Baker Author of "A Dictionary of Engraving" "A good dictionary is truly very interesting reading in spite of the man who declared that such an one changed the subject too often." —S William Beck CLEVELAND WILLIAM HENRY BAKER 1908 Copyright 1908 By William Henry Baker Cleveland O LIBRARY of CONGRESS Two Copies NOV 24 I SOB Copyright tntry _ OL^SS^tfU XXc, No. Press of The Britton Printing Co Cleveland tf- ?^ Dedication Conforming to custom this unconventional book is Dedicated to those most likely to be benefitted, i. e., to The 15000 or so Retail Clothiers The 15000 or so Custom Tailors The 1200 or so Clothing Manufacturers The 5000 or so Woolen and Cotton Mills The 22000 -

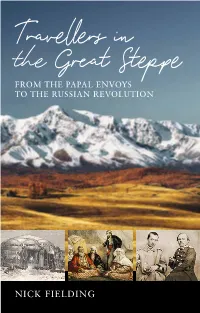

Nick Fielding

Travellers in the Great Steppe FROM THE PAPAL ENVOYS TO THE RUSSIAN REVOLUTION NICK FIELDING “In writing this book I have tried to explain some of the historical events that have affected those living in the Great Steppe – not an easy task, as there is little study of this subject in the English language. And the disputes between the Russians and their neighbours and between the Bashkirs, the Kazakhs, the Turkomans, the Kyrgyz and the Kalmyks – not to mention the Djungars, the Dungans, the Nogai, the Mongols, the Uighurs and countless others – means that this is not a subject for the faint-hearted. Nonetheless, I hope that the writings referred to in this book have been put into the right historical context. The reasons why outsiders travelled to the Great Steppe varied over time and in themselves provide a different kind of history. Some of these travellers, particularly the women, have been forgotten by modern readers. Hopefully this book will stimulate you the reader to track down some of the long- forgotten classics mentioned within. Personally, I do not think the steppe culture described so vividly by travellers in these pages will ever fully disappear. The steppe is truly vast and can swallow whole cities with ease. Landscape has a close relationship with culture – and the former usually dominates the latter. Whatever happens, it will be many years before the Great Steppe finally gives up all its secrets. This book aims to provide just a glimpse of some of them.” From the author’s introduction. TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE For my fair Rosamund TRAVELLERS IN THE GREAT STEPPE From the Papal Envoys to the Russian Revolution NICK FIELDING SIGNAL BOOKS . -

SPECIAL ANNUAL YEARBOOK EDITION Featuring Bilateral Highlights of 27 Countries Including M FABRICS M FASHIONS M NATIONAL DRESS

Published by Issue 57 December 2019 www.indiplomacy.com SPECIAL ANNUAL YEARBOOK EDITION Featuring Bilateral Highlights of 27 Countries including m FABRICS m FASHIONS m NATIONAL DRESS PLUS: SPECIAL COUNTRY SUPPLEMENT Historic Singapore President’s First State Visit to the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia CONTENTS www.indiplomacy.com PUBLISHER’S NOTE Ringing in 2020 on a Positive Note 2 PUBLISHER Sun Media Pte Ltd EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Nomita Dhar YEARBOOK SECTION EDITORIAL Ranee Sahaney, Syed Jaafar Alkaff, Nishka Rao Participating foreign missions share their highlights DESIGN & LAYOUT Syed Jaafar Alkaff, Dilip Kumar, of the year and what their countries are famous for 4 - 56 Roshen Singh PHOTO CONTRIBUTOR Michael Ozaki ADVERTISING & MARKETING Swati Singh PRINTING Times Printers Print Pte Ltd SPECIAL COUNTRY SUPPLEMENT A note about Page 46 PHOTO SOURCES & CONTRIBUTORS Sun Media would like to thank - Ministry of Communications & Information, Singapore. Singapore President’s - Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Singapore. - All the foreign missions for use of their photos. Where ever possible we have tried to credit usage Historic First State Visit and individual photographers. to Saudi Arabia PUBLISHING OFFICE Sun Media Pte Ltd, 20 Kramat Lane #01-02 United House, Singapore 228773 Tel: (65) 6735 2972 / 6735 1907 / 6735 2986 Fax: (65) 6735 3114 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.indiplomacy.com MICA (P) 071/08/2019 © Copyright 2020 by Sun Media Pte Ltd. The opinions, pronouncements or views expressed or implied in this publication are those of contributors or authors. They do not necessarily reflect the official stance of the Indonesian authorities nor their agents and representatives. -

14K Penture" Inside Band "�G� 14X" ,";

O O L .- __,_ '92'..». 8 - <.~.n-15 CG 87-41578 i . Deacription___ot Rin|;} e!! IE! Color nqq 67> Set engagement and band!; "14x 30342 932506" ,4-75?}, 1 diamond engagement Yellow 3..-7--_-7'-."MK Princess" inside hand -@ ".15 115.00" »u¢E2L-92.es! Set engagementand band!; "14: ani32 aaaooa" ' '.._.._ 1 diamond engagement Yellow :13 "l4K Princes! inside band "as.oo" ' gin , =41 es! Set engagement and band!; "14x 1n4as 911500" 3 diamond engagement Yellow %a§& "MK R-incese inaide bnnd "25-31 aes.oo" M 70! Set engagementand band!; "Gem of Love" Yellow 1 diamond engagement "MK Gem of Love" imeide "#I1l1 PEGGY 200.00" bend -bid! $3-5:?!-1 M1,: ;:':92§71! Set engagementand band!; "14! 5D188 914750 Yellow l diamond engagement 1 diamond hand "lé Princess" inside band ".24 299.50" .'~_.-.»<-_~.72! 4."-.=~ »-'.;~.' . 1?1 Set engagement and band!; "Gem oi Love White lddiamond engagement 5 diamond band "MK Ikincesa" inside bend "#Il06 IAIDA 300 . 00" 73! " "$2.3:-3;"= Set engagement and bend!; "IQK 3D354 912500" Yellow 3311 1:»*~r1=.'._ 2'-T1 l diamond engagement '71:=@_1-- >~.=~ ¢.<;-."-1+ 1-= -i "14! Princess" inside band ".22 259.50 T¢}921j.;>-7~=_q ~.s 74! =i§,§¢L1-2,5 Set engagement and band!; "Gem oi Love" Yellov iii 1 diamond engagement "MK Gem of Love" inside "#Lll5 leg 275.00" band ,,.,,.._.. .... 75! _-4;. ,_,_... Set engagement and band!; "l4KBDl93 916250" Yellow .. 5 diamond engagement 5 diamond band "14! gJ "inside hand "3029 339.00" Yellow Q O 9 CG 87-41878 >49 ,,,....,_0 ~ . -

Folklore Electronic Journal of Folklore Printed Version Vol

Folklore Electronic Journal of Folklore http://www.folklore.ee/folklore Printed version Vol. 66 2016 Folk Belief and Media Group of the Estonian Literary Museum Estonian Institute of Folklore Folklore Electronic Journal of Folklore Vol. 66 Edited by Mare Kõiva & Andres Kuperjanov Guest editors: Irina Sedakova & Nina Vlaskina Tartu 2016 Editor in chief Mare Kõiva Co-editor Andres Kuperjanov Guest editors Irina Sedakova, Nina Vlaskina Copy editor Tiina Mällo News and reviews Piret Voolaid Design Andres Kuperjanov Layout Diana Kahre Editorial board 2015–2020: Dan Ben-Amos (University of Pennsylvania, USA), Larisa Fialkova (University of Haifa, Israel), Diane Goldstein (Indiana University, USA), Terry Gunnell (University of Iceland), Jawaharlal Handoo (University of Mysore, India), Frank Korom (Boston University, USA), Jurij Fikfak (Institute of Slovenian Ethnology), Ülo Valk (University of Tartu, Estonia), Wolfgang Mieder (University of Vermont, USA), Irina Sedakova (Russian Academy of Sciences). The journal is supported by the Estonian Ministry of Education and Research (IUT 22-5), the European Union through the European Regional Development Fund (Centre of Excellence in Estonian Studies), the state programme project EKKM14-344, and the Estonian Literary Museum. Indexed in EBSCO Publishing Humanities International Complete, Thomson Reuters Arts & Humanities Citation Index, MLA International Bibliography, Ulrich’s Periodicals Directory, Internationale Volkskundliche Bibliographie / International Folklore Bibliography / Bibliographie Internationale -

Mixed Supplement

The Black Book The Black Book Part Two MIXED SUPPLEMENT Supplement entries sell on Thursday, November 7, 2019, and Friday, November 8, 2019 All of the horses/shares in this supplement sell according to the Terms and Conditions of Sale as listed in the 2019 edition of The Black Book Part Two. MIXED SALE SUPPLEMENT CATALOG SCHEDULE OF SALE THURSDAY, NOVEMBER 7 Stallion Shares (7) Hip Nos. 1800 – 1806 To be sold immediately after Stallion Shares, Hip #1024 Thursday Supplement Horses Hip Nos. 1807 – 1821 To be sold immediately after Barren Broodmares, Hip #1281 FRIDAY, NOVEMBER 8 Friday Supplement Horses Hip Nos. 1900 – 1932 To be sold immediately after Maiden Colts, Horses, and Geldings, Hip #1696 Consigned by CONCORD STUD FARM, AGENT, Cream Ridge, NJ 1 share of MUSCLE HILL 3,1:50.1 (Stallion Share #40) 1800 Foaled February 15, 2006 Stakes winner of $3,273,342. Dan Patch, Nova 2-Year-Old Trotting Colt of the Year in 2008; Dan Patch, O'Brien of the Year; Dan Patch Trotter of the Year; Dan Patch, O'Brien 3-Year-Old Trotting Colt of the Year in 2009; World Champion. At 2, winner elim. and Final Breeders Crown at Meadowlands, elim. and Final Peter Haughton Mem., Final New Jersey Sires S. at Meadowlands, Bluegrass S., International Stallion S., John Simpson Mem.; second in leg New Jersey Sires S. at Meadowlands. At 3, winner elim. and Final Hambletonian S., elim. and Final Canadian Trotting Classic, Breeders Crown at Woodbine, World Trotting Derby, Kentucky Futy., leg and Final New Jersey Sires S.