Oversight Hearing Committee on Natural Resources U.S. House of Representatives

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Legislative Hearing Committee on Natural Resources U.S

H.R. 445, H.R. 1785, H.R. 4119, H.R. 4901, H.R. 4979, H.R. 5086, S. 311, S. 476, AND S. 609 LEGISLATIVE HEARING BEFORE THE SUBCOMMITTEE ON PUBLIC LANDS AND ENVIRONMENTAL REGULATION OF THE COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES U.S. HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED THIRTEENTH CONGRESS SECOND SESSION Tuesday, July 29, 2014 Serial No. 113–84 Printed for the use of the Committee on Natural Resources ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov or Committee address: http://naturalresources.house.gov U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 88–967 PDF WASHINGTON : 2015 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Mar 15 2010 12:01 Jun 22, 2015 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 J:\04 PUBLIC LANDS & ENV\04JY29 2ND SESS PRINTING\88967.TXT DARLEN COMMITTEE ON NATURAL RESOURCES DOC HASTINGS, WA, Chairman PETER A. DEFAZIO, OR, Ranking Democratic Member Don Young, AK Eni F. H. Faleomavaega, AS Louie Gohmert, TX Frank Pallone, Jr., NJ Rob Bishop, UT Grace F. Napolitano, CA Doug Lamborn, CO Rush Holt, NJ Robert J. Wittman, VA Rau´ l M. Grijalva, AZ Paul C. Broun, GA Madeleine Z. Bordallo, GU John Fleming, LA Jim Costa, CA Tom McClintock, CA Gregorio Kilili Camacho Sablan, CNMI Glenn Thompson, PA Niki Tsongas, MA Cynthia M. Lummis, WY Pedro R. Pierluisi, PR Dan Benishek, MI Colleen W. -

Transcript of the Same

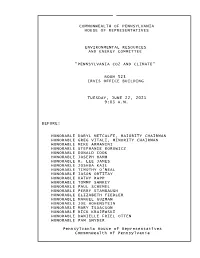

COMMONWEALTH OF PENNSYLVANIA HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ENVIRONMENTAL RESOURCES AND ENERGY COMMITTEE "PENNSYLVANIA CO2 AND CLIMATE" ROOM 523 IRVIS OFFICE BUILDING TUESDAY, JUNE 22, 2021 9:03 A.M. BEFORE: HONORABLE DARYL METCALFE, MAJORITY CHAIRMAN HONORABLE GREG VITALI, MINORITY CHAIRMAN HONORABLE MIKE ARMANINI HONORABLE STEPHANIE BOROWICZ HONORABLE DONALD COOK HONORABLE JOSEPH HAMM HONORABLE R. LEE JAMES HONORABLE JOSHUA KAIL HONORABLE TIMOTHY O'NEAL HONORABLE JASON ORTITAY HONORABLE KATHY RAPP HONORABLE TOMMY SANKEY HONORABLE PAUL SCHEMEL HONORABLE PERRY STAMBAUGH HONORABLE ELIZABETH FIEDLER HONORABLE MANUEL GUZMAN HONORABLE JOE HOHENSTEIN HONORABLE MARY ISAACSON HONORABLE RICK KRAJEWSKI HONORABLE DANIELLE FRIEL OTTEN HONORABLE PAM SNYDER Pennsylvania House of Representatives Commonwealth of Pennsylvania 2 1 COMMITTEE STAFF PRESENT: 2 GRIFFIN CARUSO 3 REPUBLICAN RESEARCH ANALYST ALEX SLOAD 4 REPUBLICAN RESEARCH ANALYST PAM NEUGARD 5 REPUBLICAN ADMINISTRATIVE ASSISTANT 6 SARAH IVERSEN 7 DEMOCRATIC EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR BILL JORDAN 8 DEMOCRATIC RESEARCH ANALYST 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 3 1 I N D E X 2 TESTIFIERS 3 * * * 4 GREG WRIGHTSTONE EXECUTIVE ASSISTANT, 5 CO2 COALITION..................................6 6 DR. DAVID LEGATES PROFESSOR OF CLIMATOLOGY 7 UNIVERSITY OF DELAWARE........................15 8 ANDREW MCKEON EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, 9 RGGI, INC.....................................30 10 MARK SZYBIST, ESQ. SENIOR ATTORNEY, 11 NATURAL RESOURCES DEFENSE COUNCIL.............38 12 FRANZ T. LITZ LITZ ENERGY STRATEGIES LLC....................45 13 DR. PATRICK MICHAELS 14 CLIMATOLOGIST, SENIOR FELLOW, CO2 COALITION.................................69 15 MARC MORANO 16 EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR, CLIMATE DEPOT.................................76 17 JOE BASTARDI 18 CHIEF FORECASTER WEATHERBELL ANALYTICS, LLC....................90 19 20 21 SUBMITTED WRITTEN TESTIMONY 22 * * * 23 (See submitted written testimony and handouts online.) 24 25 4 1 P R O C E E D I N G S 2 * * * 3 MAJORITY CHAIRMAN METCALFE: Good 4 morning. -

Do Small-Sample Short-Term Forecasting Tests Yield Valid

Forecasting global climate change Kesten C. Green University of South Australia and Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, Australia J. Scott Armstrong University of Pennsylvania, U.S.A, and Ehrenberg-Bass Institute, Australia Working Paper - June 2014 This paper was published in Climate Change: The Facts. edited by Alan Moran published by the Institute of Public Affairs, Melbourne, Victoria 3000, Australia Abstract The Golden Rule of Forecasting requires that forecasters be conservative by making proper use of cumulative knowledge and by not going beyond that knowledge. The procedures that have been used to forecast dangerous manmade global warming violate the Golden Rule. Following the scientific method, we investigated competing hypotheses on climate change in an objective way. To do this, we tested the predictive validity of the global warming hypothesis (+0.03C per year with increasing CO2) against a relatively conservative global cooling hypothesis of -0.01C per year, and against the even more conservative simple no-change or persistence hypothesis (0.0C per year). The errors of forecasts from the global warming hypothesis for horizons 11 to 100 years ahead over the period 1851 to 1975 were nearly four times larger than those from the global cooling hypothesis and about eight times larger than those from the persistence hypothesis. Findings from our tests using the latest data and other data covering a period of nearly 2,000 years support the predictive validity of the persistence hypothesis for horizons from one year to centuries ahead. To investigate whether the current alarm over global temperatures is exceptional, we employed the method of structured analogies. -

SLATE of EQUALITY Take This to the Polls with You! the Following Candidates and Ballot Measures Are Endorsed by Equality California

EQUALITY CALIFORNIA IS PROUD TO ENDORSE General Election TUESDAY NOVEMBER OF th SLATE EQUALITY Hillary Clinton Kamala Harris 8 Take this to the polls with you! PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES U.S. SENATE Prop 60: Lawsuits Against Adult Prop 52: The Medi-Cal Prop 56: CA Healthcare, Film Performers/Distributors - NO Funding and Accountability Research & Prevention Proposition 60 ignores current advances Act - YES Tobacco Tax Act of 2016 - YES in HIV prevention, such as PrEP, and would Proposition 52 would generate over $3 Proposition 56 would help save lives, be harmful to public health by driving film billion annually for Medi-Cal to increase reduce smoking and improve health care production underground or out of state. access to health care, hospital services, for members of the LGBT community and Also opposed by: California Democratic and emergency rooms for those receiving for all Californians. Also supported by: Party, California Republican Party, LA LGBT Medi-Cal services, including the estimated California Democratic Party, California Center, SF AIDS Foundation, AIDS Project Los 250,000 beneficiaries identifying as gay, Medical Association, American Lung lesbian, bisexual, and transgender. Also Angeles, along with many other health and Association, American Heart Association, supported by: California Democratic civil rights organizations. and SF AIDS Foundation. Party, California Medical Association, and California Teachers Association. Equality California’s rigorous endorsement process requires candidates to have a 100% pro-equality rating to be endorsed! PRSRT STD US POSTAGE This advertisement PAID was not authorized or BPS paid for by a candidate for this ofce or a Paid for by Equality committee controlled California PAC by a candidate for this 202 W 1st St., Suite 3-0130 ofce. -

State Delegations

STATE DELEGATIONS Number before names designates Congressional district. Senate Republicans in roman; Senate Democrats in italic; Senate Independents in SMALL CAPS; House Democrats in roman; House Republicans in italic; House Libertarians in SMALL CAPS; Resident Commissioner and Delegates in boldface. ALABAMA SENATORS 3. Mike Rogers Richard C. Shelby 4. Robert B. Aderholt Doug Jones 5. Mo Brooks REPRESENTATIVES 6. Gary J. Palmer [Democrat 1, Republicans 6] 7. Terri A. Sewell 1. Bradley Byrne 2. Martha Roby ALASKA SENATORS REPRESENTATIVE Lisa Murkowski [Republican 1] Dan Sullivan At Large – Don Young ARIZONA SENATORS 3. Rau´l M. Grijalva Kyrsten Sinema 4. Paul A. Gosar Martha McSally 5. Andy Biggs REPRESENTATIVES 6. David Schweikert [Democrats 5, Republicans 4] 7. Ruben Gallego 1. Tom O’Halleran 8. Debbie Lesko 2. Ann Kirkpatrick 9. Greg Stanton ARKANSAS SENATORS REPRESENTATIVES John Boozman [Republicans 4] Tom Cotton 1. Eric A. ‘‘Rick’’ Crawford 2. J. French Hill 3. Steve Womack 4. Bruce Westerman CALIFORNIA SENATORS 1. Doug LaMalfa Dianne Feinstein 2. Jared Huffman Kamala D. Harris 3. John Garamendi 4. Tom McClintock REPRESENTATIVES 5. Mike Thompson [Democrats 45, Republicans 7, 6. Doris O. Matsui Vacant 1] 7. Ami Bera 309 310 Congressional Directory 8. Paul Cook 31. Pete Aguilar 9. Jerry McNerney 32. Grace F. Napolitano 10. Josh Harder 33. Ted Lieu 11. Mark DeSaulnier 34. Jimmy Gomez 12. Nancy Pelosi 35. Norma J. Torres 13. Barbara Lee 36. Raul Ruiz 14. Jackie Speier 37. Karen Bass 15. Eric Swalwell 38. Linda T. Sa´nchez 16. Jim Costa 39. Gilbert Ray Cisneros, Jr. 17. Ro Khanna 40. Lucille Roybal-Allard 18. -

Fact Sheet and Q&A California Coastal National Monument

Fact Sheet and Q&A California Coastal National Monument Expansion Fast Facts • Original monument protects unappropriated or unreserved islands, rocks, exposed reefs, and pinnacles within 12 nautical miles of the California shoreline • Point Arena-Stornetta expansion protects approximately 1,665 acres in Mendocino County • Managed by the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) • Expansion adds six new areas totaling approximately 6,230 acres: o Humboldt County – Trinidad Head, Waluplh-Lighthouse Ranch, and Lost Coast Headlands o Santa Cruz County – Cotoni-Coast Dairies o San Luis Obispo County – Piedras Blancas o Orange County – Orange County Rocks and Islands What is the effect of the President’s proclamation? The President’s proclamation expands California Coastal National Monument by adding six new areas, comprised entirely of existing federal lands. The designation directs the BLM to manage these areas for the care and management of objects of scientific and historic interest identified by the proclamation. The areas generally may not be disposed of by the United States and are closed to new extractive uses such as mining and oil and gas development, and subject to valid existing rights. The designation preserves current uses of the land, including tribal access, hunting or fishing where allowed, and grazing. Will there be an opportunity for local input in the management planning process? The BLM’s planning process for the expansion areas will include opportunities for public input, consistent with the requirements of the National Environmental Policy Act and the BLM’s planning regulations and policies. The BLM will coordinate with state, local, and tribal governments as part of the planning process. -

NAR Federal Political Coordinators 115Th Congress (By Alphabetical Order )

NAR Federal Political Coordinators 115th Congress (by alphabetical order ) First Name Last Name State District Legislator Name Laurel Abbott CA 24 Rep. Salud Carbajal William Aceto NC 5 Rep. Virginia Foxx Bob Adamson VA 8 Rep. Don Beyer Tina Africk NV 3 Rep. Jacky Rosen Kimberly Allard-Moccia MA 8 Rep. Stephen Lynch Steven A. (Andy) Alloway NE 2 Rep. Don Bacon Sonia Anaya IL 4 Rep. Luis Gutierrez Ennis Antoine GA 13 Rep. David Scott Stephen Antoni RI 2 Rep. James Langevin Evelyn Arnold CA 43 Rep. Maxine Waters Ryan Arnt MI 6 Rep. Fred Upton Steve Babbitt NY 25 Rep. Louise Slaughter Lou Baldwin NC S1 Sen. Richard Burr Robin Banas OH 8 Rep. Warren Davidson Carole Baras MO 2 Rep. Ann Wagner Deborah Barber OH 13 Rep. Tim Ryan Josue Barrios CA 38 Rep. Linda Sanchez Jack Barry PA 1 Rep. Robert Brady Mike Basile MT S2 Sen. Steve Daines Bradley Bennett OH 15 Rep. Steve Stivers Johnny Bennett TX 33 Rep. Marc Veasey Landis Benson WY S2 Sen. John Barrasso Barbara Berry ME 1 Rep. Chellie Pingree Cynthia Birge FL 2 Rep. Neal Dunn Bill Boatman GA S1 Sen. David Perdue Shadrick Bogany TX 9 Rep. Al Green Bradley Boland VA 10 Rep. Barbara Comstock Linda Bonarelli Lugo NY 3 Rep. Steve Israel Charles Bonfiglio FL 23 Rep. Debbie Wasserman Schultz Eugenia Bonilla NJ 1 Rep. Donald Norcross Carlton Boujai MD 6 Rep. John Delaney Bonnie Boyd OH 14 Rep. David Joyce Ron Branch GA 8 Rep. Austin Scott Clayton Brants TX 12 Rep. Kay Granger Ryan Brashear GA 12 Rep. -

The Paper That Blew It Up

This post was published to Andy May Petrophysicist at 3:01:27 PM 11/13/2020 The Paper that Blew it Up By Andy May “If you can’t dazzle them with brilliance, baffle them with Bull…” W. C. Fields In late February 2015, Willie Soon was accused in a front-page New York Times article by Kert Davies (Gillis & Schwartz, 2015) of failing to disclose conflicts of interest in his academic journal articles. It isn’t mentioned in the Gillis and Schwartz article, but the timing suggests that a Science Bulletin article, “Why Models run hot: results from an irreducibly simple climate model” (Monckton, Soon, Legates, & Briggs, 2015) was Davies’ concern. We will abbreviate this paper as MSLB15. Besides Soon, the other authors of the paper are Christopher Monckton (senior author, Lord Monckton, Viscount of Brenchley), David Legates (Professor of Geography and Climatology, University of Delaware), and William Briggs (Mathematician and statistician, former professor of statistics at Cornell Medical School). In the January 2015 article, the authors “declare that they have no conflict of interest.” MSLB15 was instantly popular and devastating to the climate alarmist cause and to the IPCC Fifth Assessment Report (IPCC, 2013). The IPCC is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, a research organization set up by the United Nations in 1988. MSLB15 was published online January 8, 2015 and downloaded 22,000 times in less than two months, an outstanding number of downloads. The New York Times article appeared less than two months after MSLB15 hit the internet, it was a “fake news hit job.” The paper caused a stir because it explained that the IPCC’s Fifth Assessment Report or “AR5” reduced its near-term warming projections substantially, but left its long-term, higher, projections alone. -

Official List of Members by State

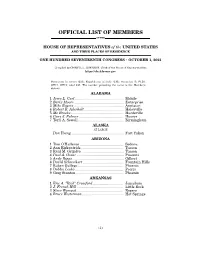

OFFICIAL LIST OF MEMBERS OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES of the UNITED STATES AND THEIR PLACES OF RESIDENCE ONE HUNDRED SEVENTEENTH CONGRESS • OCTOBER 1, 2021 Compiled by CHERYL L. JOHNSON, Clerk of the House of Representatives https://clerk.house.gov Democrats in roman (220); Republicans in italic (212); vacancies (3) FL20, OH11, OH15; total 435. The number preceding the name is the Member's district. ALABAMA 1 Jerry L. Carl ................................................ Mobile 2 Barry Moore ................................................. Enterprise 3 Mike Rogers ................................................. Anniston 4 Robert B. Aderholt ....................................... Haleyville 5 Mo Brooks .................................................... Huntsville 6 Gary J. Palmer ............................................ Hoover 7 Terri A. Sewell ............................................. Birmingham ALASKA AT LARGE Don Young .................................................... Fort Yukon ARIZONA 1 Tom O'Halleran ........................................... Sedona 2 Ann Kirkpatrick .......................................... Tucson 3 Raúl M. Grijalva .......................................... Tucson 4 Paul A. Gosar ............................................... Prescott 5 Andy Biggs ................................................... Gilbert 6 David Schweikert ........................................ Fountain Hills 7 Ruben Gallego ............................................. Phoenix 8 Debbie Lesko ............................................... -

THE CONGRESSIONAL ARTS CAUCUS 114TH CONGRESS, 1ST SESSION 164 Members As of May 4, 2015 Louise Slaughter, Co-Chair Leonard Lance, Co-Chair

THE CONGRESSIONAL ARTS CAUCUS 114TH CONGRESS, 1ST SESSION 164 Members as of May 4, 2015 Louise Slaughter, Co-Chair Leonard Lance, Co-Chair ALABAMA CONNECTICUT IOWA Terri Sewell Joe Courtney Dave Loebsack Rosa DeLauro ARIZONA Elizabeth Esty KANSAS Raúl Grijalva Jim Himes Lynn Jenkins Kyrsten Sinema John Larson KENTUCKY ARKANSAS DISTRICT OF Brett Guthrie French Hill COLUMBIA John Yarmuth Eleanor Holmes Norton CALIFORNIA LOUISIANA Julia Brownley FLORIDA John Fleming Lois Capps Corrine Brown Tony Cárdenas Vern Buchanan MAINE Susan Davis Kathy Castor Chellie Pingree Anna Eshoo Ted Deutch Sam Farr Lois Frankel MARYLAND Michael Honda Alcee Hastings Elijah Cummings Jared Huffman Patrick Murphy John Delaney Duncan Hunter Bill Posey Donna Edwards Barbara Lee Tom Rooney John Sarbanes Ted Lieu Ileana Ros-Lehtinen Chris Van Hollen Zoe Lofgren Debbie Wasserman Alan Lowenthal Schultz MASSACHUSETTS Doris Matsui Frederica Wilson Michael Capuano Tom McClintock William Keating Grace Napolitano GEORGIA Stephen Lynch Scott Peters Hank Johnson James McGovern Lucille Roybal-Allard John Lewis Richard Neal Linda Sánchez Niki Tsongas Loretta Sanchez IDAHO Adam Schiff Michael Simpson MICHIGAN Brad Sherman John Conyers Jackie Speier ILLINOIS Debbie Dingell Mark Takano Robert Dold Sander Levin Mike Thompson Danny Davis Fred Upton Luis Gutiérrez COLORADO Dan Lipinski MINNESOTA Mike Coffman Mike Quigley Keith Ellison Diana DeGette Janice Schakowsky Betty McCollum Jared Polis Rick Nolan INDIANA Erik Paulsen André Carson Collin Peterson Peter Visclosky Tim Walz All Members of the House of Representatives are encouraged to join the Congressional Arts Caucus. For more information, please contact Jack Spasiano in the office of Congresswoman Louise Slaughter at (202) 225-3615 or [email protected], or Michael Taggart in the office of Congressman Leonard Lance at (202) 225-5361 or [email protected]. -

House Organic Caucus

House Organic Caucus The House Organic Caucus is a bipartisan group of Representatives that supports organic farmers, ranchers, processors, distributors, retailers, and consumers. The Caucus informs Members of Congress about organic agriculture policy and opportunities to advance the sector. By joining the Caucus, you can play a pivotal role in rural development while voicing your community’s desires to advance organic agriculture in your district and across the country. WHY JOIN THE CAUCUS? WHAT DOES THE CAUCUS DO? • Organic, a $52.5-billion-per-year industry, is the fastest- • Keeps Members informed about opportunities to support growing sector in U.S. agriculture. organic. • Growing consumer demand for organic offers a lucrative • Serves to educate Members and their staff on: market for small, medium, and large-scale farms. • Organic farming methods • Organic agriculture creates jobs in rural America. • What the term “organic” really means • Currently, there are over 27,000 certified organic • Organic programs at the U.S. Department of Agriculture operations in the U.S. • Issues facing the growing organic industry • Organic agriculture provides healthy options for consumers. TO JOIN THE HOUSE ORGANIC CAUCUS, CONTACT: • Kris Pratt ([email protected]) in Congressman Peter DeFazio’s office • Ben Hutterer ([email protected]) in Congressman Ron Kind’s office • Travis Martinez ([email protected]) in Congressman Dan Newhouse’s office • Janie Costa ([email protected]) in Congressman Rodney Davis’s office • Kelliann Blazek ([email protected]) in Congresswoman Chellie Pingree’s office MEMBERS OF THE CAUCUS: Rep. Peter DeFazio (D-OR-04) – Co Chair Rep. -

Extensions of Remarks E916 HON. CHERI BUSTOS

E916 CONGRESSIONAL RECORD — Extensions of Remarks June 28, 2017 Ms. Wood was born in Washington, DC, Detective Williams has served every level of Authority, Director of the Bank of Marin, chair graduated from Takoma Park Academy and our community with great distinction and heart of the Novato Economic Development Com- got her degree in mass media from Loma over the past three decades. His impressive mission, member of the Bay Area Water Linda University in Southern California in career has spanned from undercover work Works Association, and president of the Gold- 1977. She reported for several stations in Ala- with the Quad-City Metropolitan Enforcement en Gate Bridge District’s Board of Directors, bama and Tennessee following her graduation Group to reduce drugs on our streets, to work- among many others. from college but was hired as the evening ing as a DARE officer in newly created drug Mr. Stroeh is survived by his wife Dawna news anchor and reporter in the Atlanta mar- education programs. Detective Williams has Gallagher-Stroeh and his beloved children: ket first by WAGA–TV, where she hosted an always gone above and beyond to strengthen Christina Stroeh, Jody Hunter, Erica Antonio, Emmy award-winning news magazine show our community in these roles, in addition to David Brown and Dona Brown, his seven called Minute by Minute. In 1997, she joined being president of the Police Benevolent As- grandchildren, five nieces and nephews, and WXlA–TV as its 6 p.m. and 11 p.m. weekday sociation. four cats. news anchor and spent the next 20 years of Detective Williams has dedicated his career Mr.