Public Transit Access to Private Property

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Vision One Eyecare Savings Programs

FLORIDA (continued) Vision One Eyecare Savings Program for Blue Cross Miami JCP Miami SEA Port Richey SEA Port Richey WR□ and Blue Shield of Florida Employees International Mall International Mall Gulf View Square Mall Gulf View Square Mall Vision Typical (305) 470-7866 (813) 846-6235 (813) 849-6783 (305) 594-5865 One Cost Savings Miami SEA Miami JCP Sarasota JCP Sarasota SEA Townand Country Mall Cutler Ridge Mall Sarasota Square Mall Sarasota Square Mall FRAMES (305) 270-9255 (305) 252-2798 (813) 923-0178 (813) 921-8278 Up to $54.00 retail $20.00 60% N. Miami Beach BRO Naples SEA St Petersburg WR□ St Petersburg JCP From $55.00 to $74.00 retail $30.00 60% 1333 NE 163rd St Coastland Mall Crossroads S/C Tyrone Square Mall Over $74.00 retail 50% 50% (305) 940-4325 (813) 643-9334 (813) 347-9191 (813) 344-2611 LENSES (uncoated plastic) Ocala JCP Ocala SEA St Petersburg SEA Tallahassee JCP Single vision $30.00 50% Ppddock Mall Paddock Mall TyroneSquare Mall Governor's Square Mall Bifocal $52.00 40% (904) 237-0055 (904) 873-5270 (813) 341-7263 (904) 878-5721 Trifocal $62.00 45% Orange Park JCP Orange Park SEA Tallahassee SEA Tampa JCP Lenticular $97.00 60% Orange Park Mall Orange Park Mall Governor's Square Mall Eastlake Square Mall LENS OPTIONS (904) 264-7070 (904) 269-8239 (904) 671-6278 (813) 621-7551 (add to above lens prices) Orlando BRO Orlando JCP Tampa WR□ Tampa BRO Progressive (no line bifocals) $55.00 20% Fashion Square Mall Fashion Square Mall Eastlake Square Mall Tampa Bay Center Polycarbonate $30.00 40% (407) 896-5398 (407) 896-1006 (813) 621-5290 (813) 872-3185 Scratch resistant coating $15.00 25% Orlando SEA Orlando JCP Tampa SEA Tampa WR□ Ultra-violet coating $12.00 40% Fashion Square Mall Florida Mall Tampa Bay Center Tampa Bay Center Anti-Reflective Coating $38.00 25% (407) 228-6239 (407) 851-9133 (813) 878-9262 (813) 876-0445 Solid tint $ 8.00 33% Orlando SEA Ormond Beach SEA Tampa JCP Tampa SEA Gradient tint $12.00 20% Florida Mall 126 S. -

Senior Resource Guide

SENIOR RESOURCE GUIDE Non-Profit and Public Agencies Serving NORTH ALAMEDA COUNTY Alameda ● Albany ● Berkeley ● Emeryville ● Oakland ● Piedmont Senior Information & Assistance Program – Alameda County Area Agency on Aging 6955 Foothill Blvd, Suite 143 (1st Floor), Oakland, CA 94605; 1-800-510-2020 / 510-577-3530; http://seniorinfo.acgov.org Office Hours : 8:30am – 4pm Monday – Friday ADULT DAY CARE/RESPITE (useful website: www.daybreakcenters.org): Alzheimer's Services of the East Bay - ASEB, Berkeley, www.aseb.org .................................................................................................................................... 510-644-8292 Bay Area Community Services - BACS, Oakland, http://bayareacs.org ................................................................................................................................... 510-601-1074 Centers for Elders Independence - CEI, (PACE - Program of All-inclusive Care for the Elderly); www.cei.elders.org ..................................................... 844-319-1150 DayBreak Adult Care Centers, (personalized referrals & community education); http://daybreakcenters.org ................................................................ 510-834-8314 Hong Fook Adult Day Health Care, Oakland, (14th Street site); www.fambridges.org ........................................................................................................ 510-839-9673 Hong Fook Adult Day Health Care, Oakland, (Harrison Street site); www.fambridges.org ................................................................................................ -

Strategic Advice for the Real Estate Community and Retailers. Since 1969

Strategic advice for the real estate community and retailers. Since 1969. Retail properties Residential properties Shopco Properties LLC Commercial properties www.shopcogroup.com Marc Yassky Joseph Speranza Principal Principal [email protected] [email protected] 424 Madison Ave 16th floor 485 Madison Ave 22nd floor New York NY 10017 New York NY 10122 212 223 1270 212 594 9400 212 202 7777 fax 888 308 1030 fax ABOUT US Shopco Properties LLC is a real estate consultancy firm focused on retail centers and multifamily residential buildings, offering strategic advice regarding development, redevelopment, finance, construction, leasing, management, marketing, and acquisition and disposition. Shopco’s depth of experience comes from the firm’s history as a developer and acquirer of regional malls, other shopping centers, and multifamily projects, across the nation. Founded in 1969, its primary focus has been retail, residential, and commercial real estate. Along with the company’s development and acquisition activities, Shopco acts as a consultant to a variety of clients, including Wall Street firms engaged in real estate lending, development and workouts, developers, private equity funds, family offices with real estate holdings, and retail ten- ants seeking locations. Clients include or have included: Lehman Brothers, JPMorgan Chase Bank, Swedbank, and Tishman Speyer, amongst others. Since the company is a small one, the principals’ experience and expertise is directly available to our clients. Our history of developing, as well as redeveloping and operating retail, residential and commercial projects, gives us particular insight when serving our customers. Shopco Properties LLC www.shopcogroup.com HISTORY Shopco was founded in 1969 to develop enclosed regional malls. -

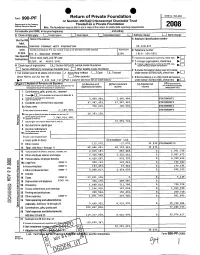

Form 990-PF Return of Private Foundation

0 0 Return of Private Foundation OMB No 1545-0052 Form 990-PF or Section 4947(a)(1) Nonexempt Charitable Trust Department of the Treasury Treated as a Private Foundation Internal Revenue Service 2008 Note. The foundation may be able to use a copy of this return to satisfy state reporting requirements. For calendar year 2008 , or tax year beginning , and ending G Check all that apply Initial return Final return Amended return L_J Address change Name change A Employer identification number Use the IRS Name of foundation label. Otherwise, HARLES STEWART MOTT FOUNDATION 38-1211227 print Number and street (or P 0 box number if mail is not delivered to street address ) Room/su to B Telephone number or type . 03 S. SAGINAW STREET 200 (810) 238-5651 See Specific City or town, state, and ZIP code C If exemption application is pending, check here Instructions . ► LINT MI 48502-1851 D 11.Foreign organizations, check here • 2. Foreign organizations meeting the 85% test. H Check typea of organization: XSection 501 (c)(3) exempt private foundation check here and attach computation = Section 4947(a)( 1 ) nonexemp t charitable trus t 0 Other taxable private foundation E If private foundation status was terminated I Fair market value of all assets at end of year J Accounting method: L_J Cash X Accrua l under section 507(b)(1)(A), check here (from Part ll, col (c), line 16) 0 Other (specify) F If the foundation is in a 60-month termination 1 933 , 369 747. (Part 1, column (d) must be on cash basis) under section 507(b)(1)(B), check here Part I Analysis of Revenue and Expenses (a) Revenue and (b) Net investment (c) Adjusted net (d) Disbursements (The total of amounts in columns ( b), (c), and (d) may not for charitable purposes necessarily equal the amounts in column (a) ex p enses p er books income income (cash basis only) 1 Contributions, gifts, grants, etc., received 2 Check it the foundation is not required to attach Sch B on savings and temporary 3 , 460 , 484. -

CDPH/OA/ADAP) Pharmacy Network Listing June 24, 2016

California Department of Public Health Office of AIDS, AIDS Drug Assistance Program (CDPH/OA/ADAP) Pharmacy Network Listing June 24, 2016 DIRECTORY OF CITIES Directory of cities .......................................................................................................................................................1 ACTON, CA ........................................................................................................................................................... 20 ADELANTO, CA ..................................................................................................................................................... 21 ALAMEDA, CA ...................................................................................................................................................... 22 ALBANY, CA .......................................................................................................................................................... 23 ALHAMBRA, CA .................................................................................................................................................... 24 ALISO VIEJO, CA ................................................................................................................................................... 25 ALTADENA, CA ..................................................................................................................................................... 26 AMERICAN CANYON, CA ..................................................................................................................................... -

Uniquely Oakland San Francisco Business Times

SPECIAL ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT SEPTEMBER 6, 2019 Uniquely OaklandOpportunities shine in California’s most inclusive and innovative city 2 ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT UNIQUELY OAKLAND SAN FRANCISCO BUSINESS TIMES Welcome to Mandela Station MANDELA STATION @WEST OAKLAND BART A Culture-Rich Transit Oriented Development 7TH ST T2 T1 Located at the 5.5-acre West Oakland Bart Station Site T3 T4 5TH ST A Centrally Located 750 Residential Units Opportunity Zone Project (approx. 240 units below market-rate) 500,000 sq.ft. of Class A oce space Only 7 minutes from Downtown San Francisco (via BART) 75,000 sq.ft. of quality retail Over 400 parking stalls Only 4 minutes to Downtown PROJ. # 168-153 WO BART Oakland (via BART) DATE: April 30, 2019 SHEET: A Regional Community...Connected JRDV ARCHITECTS INC. COPYRIGHT C 2015. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED. We’re on the Edge - and taking transit oriented living to the next level. www.westoaklandstation.com #WOSTATION [email protected] 中国港湾工程有限 公司 Strategic Urban Development Alliance, LLC China Harbour Engineering Company Ltd. suda SEPTEMBER 6, 2019 UNIQUELY OAKLAND ADVERTISING SUPPLEMENT 3 ‹ A LETTER FROM THE MAYOR OF OAKLAND › Uniquely Oakland Everyone belongs in the world’s best city for smart businesses, large or small elcome to Oakland, Calif., the best place ment dollars are pouring in, driving construction on the planet to pursue prosperity. on 240,000 square feet of new retail space and W If that seems like exaggeration, 945,000 square feet of new office space with consider this: Oakland is ideally located at the openings slated for 2019, 2020 and 2021. -

Civic Sideshows: Communities and Publics in East Oakland by Cristina Cielo

ISSC WORKING PAPER SERIES 2004-2005.01 Civic Sideshows: Communities and Publics in East Oakland by Cristina Cielo Sociology University of California, Berkeley November 16, 2005 Cristina Cielo Department of Sociology University of California, Berkeley [email protected] How do urban spatial practices contribute to the formation of collective identities and action and to the hierarchical structures of a city’s varied communities? This paper examines this question by presenting a comparative case study of two East Oakland public spaces – the streets and parks of a residential neighborhood and the hybrid public spaces of the Eastmont Town Center. A comparative analysis of the implicit property relations and “publics” produced at each site shows that, despite their differences, these spaces and their attendant collectivities share the same fundamental logic and limits. i 1 Introduction East Oakland’s city spaces do not bustle. In part, the silence of Oakland’s streets is rooted in its 1920s physical design in the idyllic suburban image of the ‘industrial garden.’ But we must follow its history into the present – through industrial and then commercial disinvestment in the area, changing demographics, rising unemployment and crime, and the forging of its contemporary identity – to understand what does go on in the area and why it looks so different from other parts of Oakland. In this paper, I examine two very different public spaces in East Oakland, the streets and parks of a residential neighborhood and the hybrid public spaces of the Eastmont Town Center. In these places, as elsewhere, both the state and the market’s inability to address local concerns has led residents to seek alternative means to meet their needs. -

Vision Care Participating Network Providers

DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA Eye Rx Dr. Vincent Bertomeu Dr. Richard S. Simon Dr. Stephen C. Lobaugh Dr. Ali Ghanbari 2021 L. St Nw Dr. Benjamin M. Teller Dr. Jing Guo Washington DC 20036 WASHINGTON Ste 502 Dr. Sun Kim (202) 659-5575 (*) <e> 1629 K. St Nw 1776 Eye Street Nw Dr. Glenn P. Allouche Washington DC 20006 # Washington DC 20006 # Dr. Samuel Stoleru 1201 F. St Nw (202) 659-2010 (S) (202) 331-3931 4119 Connecticut Ave Nw Washington DC 20004 # Washington DC 20008 # (202) 347-9260 (*) For Eyes Myeyedr (202) 966-4008 (*) 1304 G. St Nw Dr. Steven E. Abraham America`s Best Contacts & Ey Washington DC 20005 Dr. Vincent Bertomeu Visionary Ophthalmology Llc Dr. John Bankowski (202) 737-2222 (*) <d> Dr. Evelyn Dearing Dr. Leonard M. Friedman Dr. Maribel O. Bregu Dr. Ali Ghanbari Dr. Andrew Hammer Dr. Brian M. Cohen For Eyes Dr. Eric W. Goulston Dr. Babak Hosseini Dr. Ruby Y. Cooper 2021 L. St Nw Dr. Jing Guo Dr. Shirley P. Middleton Dr. Yasmine Fozooni Washington DC 20036 Dr. Danah Harbi Dr. Nima S. Moainie Dr. William R. Moughon (202) 659-0077 (*) <d> Dr. Sun Kim Dr. Luvy L. Riveros Dr. Chinweuba K. Obi Dr. Nick Neagle Dr. Maliha Saeed 1100 Connecticut Avenue Nw Dr. Leonard M. Friedman Dr. Cynthia Reynolds Temple Ste 125 Washington DC 20036 Ste 211 233 Pennsylvania Ave Se 4301 Connecticut Ave Nw (202) 223-1050 4201 Connecticut Ave Nw Washington DC 20003 # Washington DC 20008 # Washington DC 20008 (202) 544-9220 (202) 362-4545 (*) (S) Dr. Charles Aneke (202) 362-4545 (*) <e> Ste 1 Myeyedr Visionworks 5221 Georgia Ave Nw Dr. -

Pari Passu Loans in Cmbs 2.0 Last Updated: January 5, 2018

PARI PASSU LOANS IN CMBS 2.0 LAST UPDATED: JANUARY 5, 2018 % of % of Has Issuance Issuance Cut-Off Pari Master Special Master Special B DBRS Property State or Origination Trust Whole-Loan Balance at Passu Pari Passu Servicer Servicer Servicer Servicer Number note Rated Property Name Deal Name Type Country City Province Year Balance Balance Issuance in Deal Piece (Loan) (Loan) (Transaction) (Transaction) 1 no 111 Livingston Street CD 2017-CD3 Office US Brooklyn NY 2017 67,000,000 120,000,000 5.05% 55.83% A-1, A-3 Midland Midland Midland Midland 1 no 111 Livingston Street CGCMT 2017-P7 Office US Brooklyn NY 2017 29,000,000 120,000,000 2.83% 24.17% A-2 Midland Midland Wells Fargo Rialto 1 yes 111 Livingston Street CD 2017-CD4 Office US Brooklyn NY 2017 24,000,000 120,000,000 2.67% 20.00% A-4 Midland Midland Midland Rialto 2 yes 1155 Northern Boulevard PFP 2017-4 Office US Manhasset NY 2017 9,523,109 11,630,063 1.46% 81.88% N/A Wells Fargo Wells Fargo Wells Fargo Wells Fargo 1166 Avenue of the 3 yes yes BBCMS 2017-C1 Office US New York NY 2017 56,250,000 110,000,000 6.57% 66.18% A-1 Wells Fargo Rialto Wells Fargo Rialto Americas 1166 Avenue of the 3 yes yes WFCM 2017-RB1 Office US New York NY 2017 28,750,000 110,000,000 4.51% 33.82% A-2 Wells Fargo Rialto Wells Fargo C-III Americas 4 yes 123 William Street WFCM 2017-RB1 Office US New York NY 2017 62,500,000 140,000,000 9.80% 44.64% A-1 Wells Fargo C-III Wells Fargo C-III 4 yes 123 William Street MSC 2017-H1 Office US New York NY 2017 50,000,000 140,000,000 4.59% 35.71% A-2 Wells Fargo C-III -

2 Revisions to the Draft EIR

2 Revisions to the Draft EIR This section includes the revisions to the Draft EIR. These revisions have been made in response to comments or based on review by the EIR preparers. The Final EIR includes responses to all comments received during the public comment period as well as late comments received through June 13. MTC and ABAG have refined the Draft Plan Bay Area (“Draft Plan”) based upon agency and public comments. The changes to the Draft Plan as described below do not alter the conclusions presented in the Draft EIR regarding significant environmental impacts or mitigation measures and therefore do not trigger recirculation. However, this section includes revisions to the Draft EIR so that it continues to correspond to the Draft Plan. 2.1 Description of Modifications Minor modifications have been made to the housing and employment distributions in the Draft Plan. These modifications take into account the considerable local input received on the land use plan to date. Specifically, the modifications reflect: (1) corrections to datasets that were used to develop the jobs and housing distributions in the Draft Plan; (2) adjustments to ensure consistency with Regional Housing Needs Allocation (RHNA); and (3) adjustments to local jurisdictions growth based on corrections to how the distribution methodology was applied. These modifications are described in more detail below. These minor modifications do not affect the conclusions of significance in the Draft EIR, nor do they impact the regional modeling results in a significant way. CORRECTIONS TO DATA SETS Several minor errors in the data used to develop the employment and housing distributions were identified both by ABAG staff and local jurisdictions. -

Oakland Oversight Board

OAKLAND OVERSIGHT BOARD R ESOLUTION N O . 2014- A RESOLUTION APPROVING A REVISED LONG-RANGE PROPERTY MANAGEMENT PLAN ADDRESSING THE DISPOSITION AND USE OF FORMER REDEVELOPMENT AGENCY PROPERTIES, AND AUTHORIZING THE DISPOSITION OF PROPERTY PURSUANT TO THE PLAN WHEREAS, Health and Safety Code Section 34191.5(b) requires a successor agency to prepare and submit for approval to the oversight board and the California Department of Finance a long-range property management plan within six months of receiving a finding of completion; and WHEREAS, Health and Safety Code Section 34191.5(c) requires that the long- range property management plan include certain information and address the disposition and use of real property that was owned by the former redevelopment agency; and WHEREAS, the Oakland Redevelopment Successor Agency (“ORSA”) received its Finding of Completion under Health and Safety Code Section 34179.7 from the California Department of Finance on May 29, 2013; and WHEREAS, ORSA prepared and approved the original Long-Range Property Management Plan that addressed the disposition and use of real property formerly owned by the Redevelopment Agency of the City of Oakland on July 2, 2013, ORSA Resolution No. 2013-022; and WHEREAS, the original Oakland Oversight Board approved this Long-Range Property Management Plan on July 15, 2013, Oversight Board Resolution No. 2013-14; and WHEREAS, the Long-Range Property Management Plan was rejected by the California Department of Finance on February 28, 2014; and WHEREAS, ORSA has prepared and approved -

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address

Store # State City Mall/Shopping Center Name Address Date 2918 AL ALABASTER COLONIAL PROMENADE 340 S COLONIAL DR NOW OPEN! 152 AL BESSEMER COLONIAL PROMENADE AT TANNEHILL 4835 PROMENADE PKWY NOW OPEN! 1650 AL FLORENCE REGENCY SQUARE 301 COX CREEK PKWY (RT 133) NOW OPEN! 2994 AL FULTONDALE PROMENADE FULTONDALE 3363 LOWERY PKWY NOW OPEN! 2218 AL HOOVER RIVERCHASE GALLERIA 2300 RIVERCHASE GALLERIA NOW OPEN! 219 AL MOBILE THE SHOPPES AT BEL AIR 3299 BEL AIR MALL NOW OPEN! 2840 AL MONTGOMERY EASTDALE MALL 1000 EASTDALE MALL NOW OPEN! 2956 AL PRATTVILLE HIGH POINT TOWN CENTER COBBS FORD RD & BASS PRO BLVD NOW OPEN! 2875 AL SPANISH FORT SPANISH FORT TOWN CENTER 22500 TOWN CENTER AVE NOW OPEN! 2869 AL TRUSSVILLE TUTWILER FARM 5060 PINNACLE SQ NOW OPEN! 1786 AL TUSCALOOSA UNIVERSITY MALL 1701 MACFARLAND BLVD E NOW OPEN! 2265 AR PINE BLUFF THE PINES MALL 2901 PINES MALL DR STE A NOW OPEN! 2709 AR FAYETTEVILLE NORTHWEST ARKANSAS MALL 4201 N SHILOH DR NOW OPEN! 1961 AR FORT SMITH CENTRAL MALL 5111 ROGERS AVE NOW OPEN! 2835 AR JONESBORO MALL AT TURTLE CREEK 3000 E HIGHLAND DR STE 516 NOW OPEN! 2914 AR LITTLE ROCK SHACKLEFORD CROSSING 2600 S SHACKLEFORD RD NOW OPEN! 663 AR NORTH LITTLE ROCK MCCAIN SHOPPING CENTER 3929 MCCAIN BLVD STE 500 NOW OPEN! 2879 AR ROGERS PINNACLE HLLS PROMENADE 2202 BELLVIEW RD NOW OPEN! 2936 AZ CASA GRANDE PROMENADE AT CASA GRANDE 1041 N PROMENADE PKWY NOW OPEN! 157 AZ CHANDLER MILL CROSSING 2180 S GILBERT RD NOW OPEN! 251 AZ GLENDALE ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER 7750 W ARROWHEAD TOWNE CENTER NOW OPEN! 2842 AZ GOODYEAR PALM VALLEY