The Future of Mathematics Publishing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Journal Abbreviations

Abbreviations of Names of Serials This list gives the form of references used in Mathematical Reviews (MR). not previously listed ⇤ The abbreviation is followed by the complete title, the place of publication journal indexed cover-to-cover § and other pertinent information. † monographic series Update date: July 1, 2016 4OR 4OR. A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research. Springer, Berlin. ISSN Acta Math. Hungar. Acta Mathematica Hungarica. Akad. Kiad´o,Budapest. § 1619-4500. ISSN 0236-5294. 29o Col´oq. Bras. Mat. 29o Col´oquio Brasileiro de Matem´atica. [29th Brazilian Acta Math. Sci. Ser. A Chin. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series A. Shuxue † § Mathematics Colloquium] Inst. Nac. Mat. Pura Apl. (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro. Wuli Xuebao. Chinese Edition. Kexue Chubanshe (Science Press), Beijing. ISSN o o † 30 Col´oq. Bras. Mat. 30 Col´oquio Brasileiro de Matem´atica. [30th Brazilian 1003-3998. ⇤ Mathematics Colloquium] Inst. Nac. Mat. Pura Apl. (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro. Acta Math. Sci. Ser. B Engl. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series B. English § Edition. Sci. Press Beijing, Beijing. ISSN 0252-9602. † Aastaraam. Eesti Mat. Selts Aastaraamat. Eesti Matemaatika Selts. [Annual. Estonian Mathematical Society] Eesti Mat. Selts, Tartu. ISSN 1406-4316. Acta Math. Sin. (Engl. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica (English Series). § Springer, Berlin. ISSN 1439-8516. † Abel Symp. Abel Symposia. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 2193-2808. Abh. Akad. Wiss. G¨ottingen Neue Folge Abhandlungen der Akademie der Acta Math. Sinica (Chin. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica. Chinese Series. † § Wissenschaften zu G¨ottingen. Neue Folge. [Papers of the Academy of Sciences Chinese Math. Soc., Acta Math. Sinica Ed. Comm., Beijing. ISSN 0583-1431. -

Eligible Journals (PDF)

Last Update: 2021-07-08 CUP Open Access Agreement UNIVIE 2020-01-01 until 2022-12-31 Eligible Journals Acta Neuropsychiatrica Acta Numerica Advances in Archaeological Practice Africa African Studies Review Ageing & Society Agricultural and Resource Economics Review AI EDAM AJIL Unbound American Antiquity American Journal of International Law American Journal of Law & Medicine American Political Science Review Americas Anatolian Studies Ancient Mesoamerica Anglo-Saxon England Animal Health Research Reviews Annals of Actuarial Science Annals of Glaciology Annual Review of Applied Linguistics Antarctic Science Antimicrobial Stewardship & Healthcare Epidemiology Antiquaries Journal Antiquity ANZIAM Journal Applied Psycholinguistics APSIPA Transactions on Signal and Information Processing Arabic Sciences and Philosophy Archaeological Dialogues Archaeological Reports Architectural History arq: Architectural Research Quarterly Art Libraries Journal Asian Journal of Comparative Law Asian Journal of International Law Asian Journal of Law and Society ASTIN Bulletin: The Journal of the IAA Australasian Journal of Special and Inclusive Education page 1 of 8 Australian Journal of Environmental Education Australian Journal of Indigenous Education Austrian History Yearbook Behaviour Change Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy Behavioural Public Policy Bilingualism: Language and Cognition Biological Imaging Bird Conservation International BJHS Themes BJPsych Advances BJPsych Bulletin BJPsych International BJPsych Open Brain Impairment Britannia British -

Medline-Sourced Journals Are Indicated in Green) Print-ISSN E-ISSN

Sourcerecord id Source Title (Medline-sourced journals are indicated in Green) Print-ISSN E-ISSN 18500162600 21st Century Music 15343219 21100404576 2D Materials 20531583 21100447128 3 Biotech 2190572X 21905738 21100779062 3D Printing and Additive Manufacturing 23297662 23297670 21100229836 3D Research 20926731 19700200922 3L: Language, Linguistics, Literature 01285157 145295 4OR 16194500 16142411 16400154734 A + U-Architecture and Urbanism 03899160 5700161051 A Contrario 16607880 21100399164 A&A case reports 23257237 21100881366 A&A practice 25753126 19600162043 A.M.A. American Journal of Diseases of Children 00968994 19400157806 A.M.A. archives of dermatology 00965359 19600162081 A.M.A. Archives of Dermatology and Syphilology 00965979 19400157807 A.M.A. archives of industrial health 05673933 19600162082 A.M.A. Archives of Industrial Hygiene and Occupational Medicine 00966703 19400157808 A.M.A. archives of internal medicine 08882479 19400158171 A.M.A. archives of neurology 03758540 19400157809 A.M.A. archives of neurology and psychiatry 00966886 19400157810 A.M.A. archives of ophthalmology 00966339 19400157811 A.M.A. archives of otolaryngology 00966894 19400157812 A.M.A. archives of pathology 00966711 19400157813 A.M.A. archives of surgery 00966908 21100456161 a/b: Auto/Biography Studies 21517290 11600153683 A|Z ITU Journal of Faculty of Architecture 13028324 21100780699 A+BE Architecture and the Built Environment 22123202 22147233 5800207606 AAA, Arbeiten aus Anglistik und Amerikanistik 01715410 28033 AAC: Augmentative and Alternative -

Amanda L. Folsom

Amanda L. Folsom CONTACT Amherst College https://afolsom.people.amherst.edu INFORMATION Department of Mathematics and Statistics [email protected] Amherst, MA 01002 RESEARCH Analytic and Algebraic Number Theory, Harmonic Maass Forms, Modular Forms, INTERESTS Jacobi Forms, Mock and Quantum Modular Forms, Combinatorics, Lie Theory EDUCATION Ph.D. Mathematics University of California, Los Angeles Jun. 2006 Advisor: William D. Duke M.S. Mathematics University of California, Los Angeles Dec. 2002 B.A. Mathematics University of Chicago (with honors) Jun. 2001 EMPLOYMENT · Amherst College Full Professor 2019 – Department Chair 2019 – 2021 Associate Professor 2014 – 2019 · Yale University Associate Professor 2014 Assistant Professor 2010 – 2014 · University of Wisconsin-Madison NSF Postdoctoral Fellow 2007 – 2010 · Max-Planck-Institut für Mathematik, Bonn Postdoc Fellow 2006 – 2007 VISITING · Institute for Advanced Study, Princeton Spr. 2019, Spr. 2016 POSITIONS von Neumann Fellow and Member (most while on · Max-Planck-Institut für Mathematik, Bonn Sum.2022, Fall2015, Spr.2013 sabbatical leaves) Visiting Scientist · Emory University Fall 2012 GRANTS · AMS Mary P. Dolciani Prize for Excellence in Research 2021 AND AWARDS · National Science Foundation Grant (P.I.) 2019 – 2022 DMS-1901791, $252,174 · A.M. (hon.), Amherst College 2019 · Simons Fellow in Mathematics, Simons Foundation 2018 – 2019 ID 561663, $112,155 · Prose Award, Association of American Publishers 2018 Best Scholarly Book in Mathematics · National Science Foundation CAREER Grant -

Abbreviations of Names of Serials

Abbreviations of Names of Serials This list gives the form of references used in Mathematical Reviews (MR). ∗ not previously listed The abbreviation is followed by the complete title, the place of publication x journal indexed cover-to-cover and other pertinent information. y monographic series Update date: January 30, 2018 4OR 4OR. A Quarterly Journal of Operations Research. Springer, Berlin. ISSN xActa Math. Appl. Sin. Engl. Ser. Acta Mathematicae Applicatae Sinica. English 1619-4500. Series. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 0168-9673. y 30o Col´oq.Bras. Mat. 30o Col´oquioBrasileiro de Matem´atica. [30th Brazilian xActa Math. Hungar. Acta Mathematica Hungarica. Akad. Kiad´o,Budapest. Mathematics Colloquium] Inst. Nac. Mat. Pura Apl. (IMPA), Rio de Janeiro. ISSN 0236-5294. y Aastaraam. Eesti Mat. Selts Aastaraamat. Eesti Matemaatika Selts. [Annual. xActa Math. Sci. Ser. A Chin. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series A. Shuxue Estonian Mathematical Society] Eesti Mat. Selts, Tartu. ISSN 1406-4316. Wuli Xuebao. Chinese Edition. Kexue Chubanshe (Science Press), Beijing. ISSN y Abel Symp. Abel Symposia. Springer, Heidelberg. ISSN 2193-2808. 1003-3998. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. G¨ottingenNeue Folge Abhandlungen der Akademie der xActa Math. Sci. Ser. B Engl. Ed. Acta Mathematica Scientia. Series B. English Wissenschaften zu G¨ottingen.Neue Folge. [Papers of the Academy of Sciences Edition. Sci. Press Beijing, Beijing. ISSN 0252-9602. in G¨ottingen.New Series] De Gruyter/Akademie Forschung, Berlin. ISSN 0930- xActa Math. Sin. (Engl. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica (English Series). 4304. Springer, Berlin. ISSN 1439-8516. y Abh. Akad. Wiss. Hamburg Abhandlungen der Akademie der Wissenschaften xActa Math. Sinica (Chin. Ser.) Acta Mathematica Sinica. -

Pure Maths Cluster 12Pp 210Sq

Applied Mathematics Journals FROM CAMBRIDGE HOME TO 15 APPLIED MATHEMATICS JOURNALS including Acta Numerica and Journal of Fluid Mechanics Introduction from the Editors Cambridge University Press publishes a range of journals in mathematical sciences from mathematical Access free papers modelling to numerical analysis and the more analytic end of applied mathematics. Journal of Fluid Mechanics is the premier journal in its discipline; European Journal of Applied Mathematics publishes excellent themed issues covering topics such as Big Data and Partial Differential Equations, Biofi lms, and in applied mathematics Crime and Security; Acta Numerica remains the journal with highest Mathematical Citation Quotient. We publish two journals on behalf of the Applied Probability Trust, the Journal of Applied Probability and Visit the home for applied mathematics on Advances in Applied Probability, furthering the range of mathematical and scientifi c papers of interest to applied probability researchers. The three journals in actuarial science, ASTIN Bulletin, Annals of Actuarial Cambridge Core to access free journals content Science, and Bulletin of the Institute of Actuaries cater for those working at the interface of mathematics, as well as sample chapters from related books. statistics and fi nancial risk. Please do check out our gold open access journals also, Forum of Mathematics, Pi and Sigma, and our cambridge.org/applied-mathematics newly launched open access journal, Data Centric Engineering, with the generous support of the Lloyd’s Register Foundation. For any questions about our journal publishing please get in touch with Kathleen Too ([email protected]), Elizabeth Woodhouse ([email protected]), or Samira Ceccarelli ([email protected]). FirstView At Cambridge, we are proud to offer FirstView, our online ahead of print publishing option, for many of our pure mathematics titles. -

Collection Assessment : Computational and Applied Mathematics, USFSP, 2017

University of South Florida Scholar Commons All-Library Assessments Reports, Summaries & Library Assessment Reports, Summaries, and Misc Reports Misc Reports 8-1-2017 Collection Assessment : Computational and Applied Mathematics, USFSP, 2017 Patricia Pettijohn Nelson Poynter Memorial Library. Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/npml_collection_assessments Scholar Commons Citation Pettijohn, Patricia and Nelson Poynter Memorial Library., "Collection Assessment : Computational and Applied Mathematics, USFSP, 2017" (2017). All-Library Assessments Reports, Summaries & Misc Reports. 24. https://scholarcommons.usf.edu/npml_collection_assessments/24 This Other is brought to you for free and open access by the Library Assessment Reports, Summaries, and Misc Reports at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in All-Library Assessments Reports, Summaries & Misc Reports by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Library Assessment: Computational & Applied Mathematics August 2017 Nelson Poynter Memorial Library University of South Florida St. Petersburg Prepared by Patricia Pettijohn Overview of Library The Nelson Poynter Memorial Library, University of South Florida St. Petersburg (USFSP), houses an extensive collection of materials that supports the educational, research, and service missions of USF St. Petersburg. USF St. Petersburg faculty, staff, and student have on-site access to the Poynter Library’s collection of over 221,620 items, including monographs, current periodical and serial subscriptions, newspaper subscriptions, and audiovisual titles, as well as to the shared electronic resources of the USF System, providing USFSP students unlimited access to the vast holdings of a Carnegie Research 1 doctoral institution. This includes 1,934 journals in mathematics, over 1,800 journals in information technology, and core mathematics and computational sciences databases, e-book collections and reference resources. -

Some Successful Strategies for Promoting Mathematics in England

some successful strategies for promoting mathematics in England Professor Celia Hoyles OBE London Knowledge Lab, Institute of Education, University of London, U.K & Director of the National Centre for Excellence in the Teaching of Mathematics Goals of Government 1. to raise standards In mathematics: • internal performance tables from tests at 7, 11, (14)& 16 • TIMSS, PISA, and adult numeracy AND more recently 2. to increase participation in mathematics post-16 to achieve BOTH need • more success in mathematics and • positive attitude to mathematics & appreciation of the point of mathematics • for itself • as a tool in other subjects • for its ‘exchange value’ for individual future careers and for the country target for 2014 set in 2005/6 A level entries (specialist mathematics examination, 18years) Prov Some history: giving mathematics a policy voice ACME The Advisory Committee on Mathematics Education (ACME) was established in 2002 to act as a single voice for the mathematical community, seeking to improve the quality of education in schools and colleges Set up by the Joint Mathematical Council of the UK and the Royal Society (RS), with the explicit support of all major mathematics organisations ACME advises Government on issues such as the curriculum, assessment and the supply and training of mathematics teacher 4 7 members including teachers: part time Chair, Fellow of RS Some interventions: promoting Active Learning post-16 Numbers with more digits are The square of a number is greater in value. greater than the number. incorporating discussion & When you cut a piece off a In a group of ten learners, the the need to shape, you reduce its area and probability of two learners perimeter. -

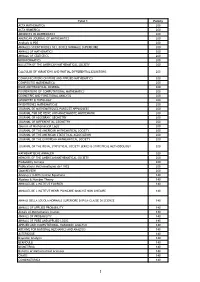

Tytuł 1 Punkty ACTA MATHEMATICA 200 ACTA NUMERICA 200

Tytuł 1 Punkty ACTA MATHEMATICA 200 ACTA NUMERICA 200 ADVANCES IN MATHEMATICS 200 AMERICAN JOURNAL OF MATHEMATICS 200 Analysis & PDE 200 ANNALES SCIENTIFIQUES DE L ECOLE NORMALE SUPERIEURE 200 ANNALS OF MATHEMATICS 200 ANNALS OF STATISTICS 200 BIOINFORMATICS 200 BULLETIN OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY 200 CALCULUS OF VARIATIONS AND PARTIAL DIFFERENTIAL EQUATIONS 200 COMMUNICATIONS ON PURE AND APPLIED MATHEMATICS 200 COMPOSITIO MATHEMATICA 200 DUKE MATHEMATICAL JOURNAL 200 FOUNDATIONS OF COMPUTATIONAL MATHEMATICS 200 GEOMETRIC AND FUNCTIONAL ANALYSIS 200 GEOMETRY & TOPOLOGY 200 INVENTIONES MATHEMATICAE 200 JOURNAL DE MATHEMATIQUES PURES ET APPLIQUEES 200 JOURNAL FUR DIE REINE UND ANGEWANDTE MATHEMATIK 200 JOURNAL OF ALGEBRAIC GEOMETRY 200 JOURNAL OF DIFFERENTIAL GEOMETRY 200 Journal of Mathematical Logic 200 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY 200 JOURNAL OF THE AMERICAN STATISTICAL ASSOCIATION 200 JOURNAL OF THE EUROPEAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY 200 JOURNAL OF THE ROYAL STATISTICAL SOCIETY SERIES B-STATISTICAL METHODOLOGY 200 MATHEMATISCHE ANNALEN 200 MEMOIRS OF THE AMERICAN MATHEMATICAL SOCIETY 200 Probability Surveys 200 Publications Mathematiques de l IHES 200 SIAM REVIEW 200 Advances in Differential Equations 140 Algebra & Number Theory 140 ANNALES DE L INSTITUT FOURIER 140 ANNALES DE L INSTITUT HENRI POINCARE-ANALYSE NON LINEAIRE 140 ANNALI DELLA SCUOLA NORMALE SUPERIORE DI PISA-CLASSE DI SCIENZE 140 ANNALS OF APPLIED PROBABILITY 140 Annals of Mathematics Studies 140 ANNALS OF PROBABILITY 140 ANNALS OF PURE AND APPLIED -

2018 Online Journals Packages

Psychology and Psychiatry Acta Neuropsychiatrica Impact Factor: 1.939 Open Access Worldwide Contacts Australian Journal of Rehabilitation Counselling, The Behavioral and Brain Sciences Impact Factor: 14.2 If you would like information about For free quotes or further information about any Behaviour Change Impact Factor: 0.658 placing funding for Open Access articles, of the online platforms and publications in this Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy Impact Factor: 1.697 Brain Impairment Impact Factor: 0.6 either through membership, prepayment, brochure, please get in touch via the following British Journal of Psychiatry, The Impact Factor: 6.347 retrospective OA or collectively as part of email addresses: BJPsych Open a subscription agreement, please contact 2018 Online Journals Packages BJPsych Advances [email protected] BJPsych Bulletin BJPsych International The following titles, listed by subject area, are available as a Full Package, a Humanities and Social Sciences (HSS) Canadian Journal of Neurological Sciences Impact Factor: 0.952 We attend the following major Package, a Science, Technology and Medicine (STM) Package and as smaller, subject based packages. Journals CNS Spectrums Impact Factor: 3.589 Americas new to Cambridge in 2018 are listed in bold. All Impact Factors results from the 2016 Journal Citation Reports Cognitive Behaviour Therapist, The conferences, please come and [email protected] (Clarivate Analytics, 2017). Development and Psychopathology Impact Factor: 3.244 visit us at: Epidemiology and Psychiatric Sciences Impact Factor: 4.246 For more information or a price proposal, please contact your usual sales agent or contact us using the information Global Mental Health Asia Industrial and Organizational Psychology Impact Factor: 1.747 • ADBU on the back cover of this leaflet. -

Cambridge University Press 2020 Iowa State OA FINAL

Publishing Agreements Collections and Open Strategies 2020 Cambridge University Press 2020 Iowa State OA FINAL Cambridge University Press Iowa State University of Science and Technology Follow this and additional works at: https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cos_agreements Recommended Citation Cambridge University Press and Iowa State University of Science and Technology, "Cambridge University Press 2020 Iowa State OA FINAL" (2020). Publishing Agreements. 3. https://lib.dr.iastate.edu/cos_agreements/3 This Report is brought to you for free and open access by the Collections and Open Strategies at Iowa State University Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publishing Agreements by an authorized administrator of Iowa State University Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. DocuSign Envelope ID: 441C5B37-CACB-4362-9C4A-8604A82813A5 Contract form for supply of products to academic institutions The Chancellor, Masters, and Scholars of the University of Cambridge acting through its department Cambridge University Press having its principal office at University Printing House, Shaftesbury Road, Cambridge, CB2 8BS, United Kingdom (“Licensor”) agrees to supply the Licensee named below certain online products on the terms set out in this contract form and the current “Licence Terms for Institutions”, as attached. Licensee Institution/organisation Contact Name Iowa State University of Science and Technology Curtis Brundy Address 701 Morrill Road Ames, IA 50011 Telephone 515-294-7563 Email [email protected] -

Employer Engagement in Undergraduate Mathematics

Employer Engagement in Undergraduate Mathematics Mathematical Sciences HE Curriculum Innovation Project Innovation Curriculum HE Sciences Mathematical Edited by Jeff Waldock and Peter Rowlett Employer Engagement in Undergraduate Mathematics Edited by Jeff Waldock and Peter Rowlett July 2012 Summary of work in mathematical sciences HE curriculum innovation Contents Contents Introduction 5 1. Industrial Problem Solving for Higher Education Mathematics 23 2. Industrial problems in statistics for the HE curriculum 27 3. A Statistical Awareness Curriculum for STEM Employees 33 4. Assessing student teams developing mathematical models applied to business and industrial mathematics 41 5. How realistic is work-related learning, and how realistic should it be? 47 6. Models of Industrial Placements for Mathematics Undergraduates 53 7. Supporting progression in mathematics education 63 8. Being a Professional Mathematician 67 9. Graduates’ Views on the Undergraduate Mathematics Curriculum – summary of findings 71 Summary of work in mathematical sciences HE curriculum innovation Introduction Introduction By ‘employer engagement’, we include various activities which involve employers, employees or professional bodies in a number of aspects of curricula and extra-curricular undergraduate activity. This booklet primarily reports on nine projects relating to employer engagement supported by the Maths, Stats and OR Network (MSOR) as part of the National HE STEM Programme. The HE Mathematics Curriculum Summit took place at the University of Birmingham on 12 January 2011 [1]. This brought together Heads of Mathematics or their representatives from 26 universities offering mathematics degrees (about half of those in England and Wales), representatives from the professional bodies, and others. One outcome of the Summit was a series of recommendations [2]; four of these relate to employer engagement and have led to five projects reported in this booklet (Projects 1, 2, 6, 8 and 9).