Michael Parsons Interviewed by Dr Thomas Lean: Full Transcript of the Interview

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

2020 Frankfurt Book Fair Catalogue (PDF)

Sharing new conversations and fresh ideas for living life well. October 2020 – July 2021 Contents AT THE TABLE 7 SUSTAINABLE LIVING 21 HOME AND FAMILY 27 PERSONAL TRANSFORMATION AND SELF HELP 37 BACKLIST 51 INDEX 75 SALES CONTACTS 78 Books for living life well. What a year it has been. Perhaps that is enough said on that! From a publishing perspective, it has reinforced our philosophy at Murdoch Books of publishing books that add value to people’s lives. What we call books for ‘living life well.’ A taste of our upcoming line-up includes food waste pioneer Ronni Kahn’s uplifting memoir, A Repurposed Life; Durkhanai Ayubi’s love letter to her family’s homeland, Parwana: Recipes and Stories from an Afghan Kitchen; Alice Zaslavsky’s joyous celebration of all things vegetable, In Praise of Veg; Bill Granger’s very grown up Australian Food; Duncan Welgemoed’s take-no- prisoners cookbook inspired by his South African Heritage and award-winning restaurant, Africola: Slow food, fast words, cult chef; bestselling international author Belinda Alexandra’s ode to the relationship between women and their cats, The Divine Feline; a first aid kit for anxiety in book form by Tammi Kirkness, The Panic Button Book; Emily Ehlers’ self help guide for the modern era, Hope is a Verb; and the mouth-watering and eye opening Amber & Rye: A Baltic food journey through Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania from Zuza Zak. Stay safe! Lou Johnson Publishing Director, Murdoch Books Lou Johnson is the Publishing Director of Murdoch Books. Kelly Doust’s career in publishing spans 20+ years in the roles She has previously held senior roles across leading publishing of publisher, publicity manager and as an author of eight books houses, including Managing Director for Simon and Schuster of fiction and non-fiction. -

The Mysterious Rider Grey, Zane

The Mysterious Rider Grey, Zane Published: 1921 Categorie(s): Fiction, Westerns Source: http://gutenberg.org 1 About Grey: Zane Grey (January 31, 1872 – October 23, 1939) was an American author best known for his popular adventure novels and pulp fiction that presented an idealized image of the rugged Old West. As of June 2007, the Internet Movie Data- base credits Grey with 110 films, one TV episode, and one en- tire TV Series based on his novels and stories. Source: Wikipedia Also available on Feedbooks for Grey: • Riders of the Purple Sage (1912) • Desert Gold (1913) • The Lone Star Ranger (1915) • The Call of the Canyon (1924) • The Border Legion (1916) • The Heritage of the Desert (1910) • The Last of the Plainsmen (1908) • Wildfire (1917) • To The Last Man (1921) • The Rustlers of Pecos County (1914) Copyright: This work is available for countries where copy- right is Life+70 and in the USA. Note: This book is brought to you by Feedbooks http://www.feedbooks.com Strictly for personal use, do not use this file for commercial purposes. 2 Chapter 1 A September sun, losing some of its heat if not its brilliance, was dropping low in the west over the black Colorado range. Purple haze began to thicken in the timbered notches. Gray foothills, round and billowy, rolled down from the higher coun- try. They were smooth, sweeping, with long velvety slopes and isolated patches of aspens that blazed in autumn gold. Splotches of red vine colored the soft gray of sage. Old White Slides, a mountain scarred by avalanche, towered with bleak rocky peak above the valley, sheltering it from the north. -

Chapter Five Land Use Control 500 Building Code

CHAPTER FIVE LAND USE CONTROL 500 BUILDING CODE This ordinance provides for the application, administration, and enforcement of the Minnesota State Building Code by regulating the erection, construction, enlargement, alteration, repair, moving, removal, demolition, conversion, occupancy, equipment, use, height, area, and maintenance of all buildings and/or structures in this municipality; provides for the issuance of permits and collection of fees thereof; provides penalties for violation thereof; repeals all ordinances and parts of ordinances that conflict therewith. This ordinance shall perpetually include the most current edition of the Minnesota state building code with the exception of the optional appendix chapters. Optional appendix chapters shall not apply unless specifically adopted. The municipality does ordain as follows: 500.01. Codes adopted by reference . The Minnesota State Building Code, as adopted by the Commissioner of Labor and Industry pursuant to Minnesota Statutes chapter 326B, including all of the amendments, rules and regulations established, adopted and published from time to time by the Minnesota Commissioner of Labor and Industry, through the Building Codes and Standards Unit, is hereby adopted by reference with the exception of the optional chapters, unless specifically adopted in this ordnance. The Minnesota State Building Code is hereby incorporated in this ordinance as if fully set out herein. 500.02. Application, Administration and Enforcement . The application, administration, and enforcement of the code shall be in accordance with Minnesota State Building Code. The code shall be enforced within the extraterritorial limits permitted by Minnesota Statutes, 326B.121, Subd. 2(d), when so established by this ordinance. The code enforcement agency of this municipality is called the Building Inspector. -

Songbook, 1920

Connecticut College Digital Commons @ Connecticut College Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Connecticut College Books Archives 1920 Songbook, 1920 Connecticut College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccbooks Recommended Citation Connecticut College, "Songbook, 1920" (1920). Connecticut College Books. 1. https://digitalcommons.conncoll.edu/ccbooks/1 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Linda Lear Center for Special Collections & Archives at Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. It has been accepted for inclusion in Connecticut College Books by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Connecticut College. For more information, please contact [email protected]. The views expressed in this paper are solely those of the author. ,-, . l' . �3,, ' �)'tnedra✓-t (tolt. ;1 �U/}7 J1?u. �ri, Qlonn.edi:cui Qloll.e_s.e �on_s.s 1915-1920 Collected by the Song Leaders of the first five classes at Connecticut College, and edited by the Class of 1920, September 1920. Dear C. C. Words by Dr ..Frederick Henry Sykes Mitstc by Dr. Louis A. Coerne There's a college, there's a college There's a college by the sea, With the hill tops all around it And a river on the lea; Where the elm trees pipe with music, And the sky is blue above, Where life is at its fairest. Filled with work and song and love. Chorus: Dear C.C., the only place for me, Where friends are true and skies are blue, My heart I give it all to you; Dear C.C., the college by the sea, The Faculty will give me my degree, Maybe. -

What Immortal Hand

What Immortal Hand What Immortal Hand By Johnny Worthen Omnium Gatherum Los Angeles What Immortal Hand Copyright © 2017 Johnny Worthen ISBN-13: 9780997971798 ISBN-10: 0997971797 All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or trans- mitted in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without the written permission of the author and publisher omniumgatherumedia.com. This book is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places and incidents are either the products of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events or persons, living or dead, is coincidental. First Edition For Kate The Tyger (from Songs of Experience) By William Blake Tyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Could frame thy fearful symmetry? In what distant deeps or skies Burnt the fire of thine eyes? On what wings dare he aspire? What the hand dare seize the fire? And what shoulder, & what art, Could twist the sinews of thy heart? And when thy heart began to beat, What dread hand? & what dread feet? What the hammer? what the chain? In what furnace was thy brain? What the anvil? what dread grasp Dare its deadly terrors clasp? When the stars threw down their spears, And watered heaven with their tears, Did he smile his work to see? Did he who made the Lamb make thee? Tyger! Tyger! burning bright In the forests of the night, What immortal hand or eye Dare frame thy fearful symmetry? 1794 6 Prologue The neckerchief whips around Isaac’s throat with a jangle of coins. -

アーティスト 商品名 フォーマット 発売日 商品ページ 555 Solar Express CD 2013/11/13

【SOUL/CLUB/RAP】「怒涛のサプライズ ボヘミアの狂詩曲」対象リスト(アーティスト順) アーティスト 商品名 フォーマット 発売日 商品ページ 555 Solar Express CD 2013/11/13 https://tower.jp/item/3319657 1773 サウンド・ソウルステス(DIGI) CD 2010/6/2 https://tower.jp/item/2707224 1773 リターン・オブ・ザ・ニュー CD 2009/3/11 https://tower.jp/item/2525329 1773 Return Of The New (HITS PRICE) CD 2012/6/16 https://tower.jp/item/3102523 1773 RETURN OF THE NEW(LTD) CD 2013/12/25 https://tower.jp/item/3352923 2562 The New Today CD 2014/10/23 https://tower.jp/item/3729257 *Groovy workshop. Emotional Groovin' -Best Hits Mix- mixed by *Groovy workshop. CD 2017/12/13 https://tower.jp/item/4624195 100 Proof (Aged in Soul) エイジド・イン・ソウル CD 1970/11/30 https://tower.jp/item/244446 100X Posse Rare & Unreleased 1992 - 1995 Mixed by Nicky Butters CD 2009/7/18 https://tower.jp/item/2583028 13 & God Live In Japan [Limited] <初回生産限定盤>(LTD/ED) CD 2008/5/14 https://tower.jp/item/2404194 16FLIP P-VINE & Groove-Diggers Presents MIXCHAMBR : Selected & Mixed by 16FLIP <タワーレコード限定> CD 2015/7/4 https://tower.jp/item/3931525 2 Chainz Collegrove(INTL) CD 2016/4/1 https://tower.jp/item/4234390 2000 And One Voltt 02 CD 2010/2/27 https://tower.jp/item/2676223 2000 And One ヘリタージュ CD 2009/2/28 https://tower.jp/item/2535879 24-Carat Black Ghetto : Misfortune's Wealth(US/LP) Analog 2018/3/13 https://tower.jp/item/4579300 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) TUPAC VS DVD 2004/11/12 https://tower.jp/item/1602263 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) 2-PAC 4-EVER DVD 2006/9/2 https://tower.jp/item/2084155 2Pac (Tupac Shakur) Live at the house of blues(BRD) Blu-ray 2017/11/20 https://tower.jp/item/4644444 -

The Top Dance Songs of 2019 1

th 45 Year THE TOP DANCE SONGS OF 2019 1. HIGHER LOVE – Kygo & Whitney Houston (RCA) 124/104 51. YOU LITTLE BEAUTY – Fisher (Astralwerks/Capitol) 124 2. PIECE OF YOUR HEART – Meduza ft. Goodboys (Capitol) 124 52. GO SLOW – Gorgon City & Kaskade ft. ROMEO (Capitol) 124 3. I DON’T CARE – Ed Sheeran & Justin Bieber (Atlantic) 122/102 53. SUMMER DAYS – Martin Garrix ft. Macklemore & Patrick Stump (RCA) 126/114 4. SUCKER – Jonas Brothers (Republic) 126/138 54. ON MY WAY – Alan Walker, Sabrina Carpenter & Farruko (RCA) 120/85 5. BAD GUY – Billie Eilish (Interscope) 126/135 55. HEY LOOK MA, I MADE IT – Panic! At The Disco (Atlantic) 124/108 6. CON CALMA – Daddy Yankee & Katy Perry ft. Snow (El Cartel/Capitol) 109/94 56. FIND U AGAIN – Mark Ronson & Camila Cabello (RCA) 124/104 7. SENORITA – Shawn Mendes & Camila Cabello (Republic) 124/117 57. BREAK UP WITH YOUR GIRLFRIEND, I’M BORED – Ariana Grande (Republic) 124/85 8. 7 RINGS/THANK U NEXT – Ariana Grande (Republic) 126/70, 124/107 58. SELFISH – Dimitri Vegas & Like Mike ft. Era Istrefi (Arista) 126/96 9. DANCING WITH A STRANGER – Sam Smith & Normani (Capitol) 123/103 59. 365 – Zedd & Katy Perry (Interscope) 124/98 10. DANCE MONKEY – Tones and I (Elektra) 122/98 60. BEAUTIFUL PEOPLE – Ed Sheeran ft. Khalid (Atlantic) 120/93 11. OLD TOWN ROAD – Lil Nas X ft. Billy Ray Cyrus (Columbia) 124/70 61. QUE CALOR – Major Lazer ft. J Balvin & El Alfa (Mad Decent) 126 12. SO CLOSE – NOTD & Felix Jaehn ft. Georgia Ku & Captain Cuts (Republic) 126 62. -

TOM SWIFT and the Martian Moon Re-Placement

TOM SWIFT And The Martian Moon Re-placement BY Victor Appleton II Thackery Fox & Associates Made in The United States of America This book is dedicated to the surgical team in Portland, Oregon who performed my quadruple heart bypass surgery the Friday before Thanksgiving this past year and got me home for Turkey Day. It happened right in the middle of writing this story and sidetracked me for more than a month, They left me with a pair of scars that might have been worse, but they took their time and got me stitched up with minimal visual evidence of them having been inside. Bravo to them and also to my fans who heard about this and wrote those wonderful emails of encouragement. Thanks all! ©opyright 2018 by the author of this book (Victor Appleton II - pseud. of Thomas Hudson). The book author asserts sole copyright to his or her contributions to this book. This book is a work of fan fiction. It is not claimed to be part of any previously published adventures of the main characters. It has been self-published and is not intended to supplant any authored works attributed to the pseudononomous author or to claim the rights of any legitimate publishing entity. However, the publisher claiming copyrights have allowed more than one of the books in their series to drop into Public Domain status and so have relinquished total control over these characters. 2 THE NEW TOM SWIFT INVENTION SERIES Tom Swift and the Martian Moon Re-placement By Victor Appleton II Small, irregular and rocky Deimos and Phobos circle the Red Planet in tight orbits. -

To Search This List, Hit CTRL+F to "Find" Any Song Or Artist Song Artist

To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Song Artist Length Peaches & Cream 112 3:13 U Already Know 112 3:18 All Mixed Up 311 3:00 Amber 311 3:27 Come Original 311 3:43 Love Song 311 3:29 Work 1,2,3 3:39 Dinosaurs 16bit 5:00 No Lie Featuring Drake 2 Chainz 3:58 2 Live Blues 2 Live Crew 5:15 Bad A.. B...h 2 Live Crew 4:04 Break It on Down 2 Live Crew 4:00 C'mon Babe 2 Live Crew 4:44 Coolin' 2 Live Crew 5:03 D.K. Almighty 2 Live Crew 4:53 Dirty Nursery Rhymes 2 Live Crew 3:08 Fraternity Record 2 Live Crew 4:47 Get Loose Now 2 Live Crew 4:36 Hoochie Mama 2 Live Crew 3:01 If You Believe in Having Sex 2 Live Crew 3:52 Me So Horny 2 Live Crew 4:36 Mega Mixx III 2 Live Crew 5:45 My Seven Bizzos 2 Live Crew 4:19 Put Her in the Buck 2 Live Crew 3:57 Reggae Joint 2 Live Crew 4:14 The F--k Shop 2 Live Crew 3:25 Tootsie Roll 2 Live Crew 4:16 Get Ready For This 2 Unlimited 3:43 Smooth Criminal 2CELLOS (Sulic & Hauser) 4:06 Baby Don't Cry 2Pac 4:22 California Love 2Pac 4:01 Changes 2Pac 4:29 Dear Mama 2Pac 4:40 I Ain't Mad At Cha 2Pac 4:54 Life Goes On 2Pac 5:03 Thug Passion 2Pac 5:08 Troublesome '96 2Pac 4:37 Until The End Of Time 2Pac 4:27 To Search this list, hit CTRL+F to "Find" any song or artist Ghetto Gospel 2Pac Feat. -

Castles & Battlefields As a PDF on Screen

A Guide for Disabled Visitors Castles & Battlefields ACCESSIBLE HIGHLIGHTS Welcome to Castles & Battlefields! All throughout Scotland there are remnants of the country’s battle-scarred past, but what few people know is that LOCH NESS many of these castles and battlefields can Urquhart Castle be unexpectedly accessible. Inside this guide you’ll find a Lochside ruin with an excellent visualisation guide; a mighty fortress with ramps wide and sturdy enough to move cannons; a THE HIGHLANDS haunted castle with wheelchair accessible gardens Elgin Cathedral that seem to go on forever; battlefields brought to life Duffus Castle by audio guides; and a hidden pine forest beach with Spynie Castle a curious story to tell. Culloden This collection of castles and battlefields is waiting to Brodie Castle ABERDEENSHIRE be explored, and we hope that it will give local and Boath Doocot Crathes Castle visiting disabled people a flavour for Scottish history; Fort George as well as practical information about accessibility Roseisle Forest before venturing out to these rural and urban ruins, Clava Cairns Burghead Pict Fort castles and historic sites. STIRLINGSHIRE Bannockburn EXPLORE FURTHER ONLINE The Wallace Monument Stirling Castle Doune Castle For disabled access reviews and more information about accessibility, visit www.euansguide.com/castles-and-battlefields to discover more about the featured locations, as well as thousands of other places including hotels, restaurants and transport. If you’ve been exploring the castles and battlefields of Scotland, as well as other places, don’t forget to share you stories by writing a review on Euan’s Guide. That way, others can benefit from your experience. -

MYSTERIES of the WORLD, P.8 * a One-Night Career Fair for Local Tech Jobs *

ALAN RHODES, P.6 FUZZ BUZZ, P.10 FOLKLIKE FEST, P.22 cascadia REPORTING FROM THE HEART OF CASCADIA WHATCOM*SKAGIT*ISLAND*LOWER B.C. 5.14.08 :: #20, v.03 :: FREE ’ FOR GROOVIN GRIZZLIES P.16 IMPROVATHON: THE SHOW THAT NEVER ENDS, P.18 WELDING RODEO: STEEL COWBOYS, P.20 SCIENCE AND SPIRIT: MYSTERIES OF THE WORLD, P.8 * A One-Night Career Fair for Local Tech Jobs * BELLINGHAM 38 38 FOOD 31 TechNight CLASSIFIEDS Tuesday - May 20, 2008 6:00pm – 9:00pm | Bellingham Cruise Terminal 26 www.BellinghamTechNight.com FILM FILM For questions, email us at [email protected] or call 360-647-4220 22 22 Hosted by MUSIC 20 20 ART NURSERY, LANDSCAPING & ORCHARDS For race day 18 and every day. STAGE UNIQUE No matter what the outing, 17 PLANTS FOR we’ve got you covered. GET OUT 16 NORTHWEST WORDS GARDENS 8 ornamentals, natives, fruit 360 543 5678 214 W. Holly Bellingham Spring: Mon-Sat 10-5, Sun 11-4 Mo - Sa 10-7 Su 12-5 CURRENTS CURRENTS . Goodwin Road, Everson www.backcountryessentials.net 6 www.cloudmountainfarm.com VIEWS VIEWS 4 MAIL MAIL 3 DO IT IT DO 08 .14. 5 .03 20 # CASCADIA WEEKLY Stop by on your way to Canada. 2 We’re one mile west of 1-5 on Grandview Rd. phone: 360-366-4013 Exit 266 in Ferndale. Spring hours Mon-Friday 9-6, Sat 10-5 cascadia CELEBRATE THE WRITTEN WORD WHENPOETSFROMNEARANDFAR CONVERGE IN LA CONNER MAY 15-17 38 38 FOR THE ANNUAL SKAGIT RIVER FOOD A glance at what’s happening this week POETRY FESTIVAL 31 THE ON ENSEMBLE WILL INJECT A CLASSIFIEDS 05.14.08 UNIVERSE OF SOUNDS INTO ITS ECLECTIC AND Hall Roller Betties Bout: 5pm, -

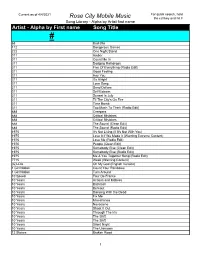

Alpha by First Name Song Title

Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title # 68 Bad Bite 112 Dangerous Games 222 One Night Stand 311 Amber 311 Count Me In 311 Dodging Raindrops 311 Five Of Everything (Radio Edit) 311 Good Feeling 311 Hey You 311 It's Alright 311 Love Song 311 Sand Dollars 311 Self Esteem 311 Sunset In July 311 Til The City's On Fire 311 Time Bomb 311 Too Much To Think (Radio Edit) 888 Creepers 888 Critical Mistakes 888 Critical Mistakes 888 The Sound (Clean Edit) 888 The Sound (Radio Edit) 1975 It's Not Living (If It's Not With You) 1975 Love It If We Made It (Warning Extreme Content) 1975 Love Me (Radio Edit) 1975 People (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Clean Edit) 1975 Somebody Else (Radio Edit) 1975 Me & You Together Song (Radio Edit) 7715 Week (Warning Content) (G)I-Dle Oh My God (English Version) 1 Girl Nation Count Your Rainbows 1 Girl Nation Turn Around 10 Speed Tour De France 10 Years Actions and Motives 10 Years Backlash 10 Years Burnout 10 Years Dancing With the Dead 10 Years Fix Me 10 Years Miscellanea 10 Years Novacaine 10 Years Shoot It Out 10 Years Through The Iris 10 Years The Shift 10 Years The Shift 10 Years Silent Night 10 Years The Unknown 12 Stones Broken Road 1 Current as of 4/4/2021 For quick search, hold Rose City Mobile Music the ctrl key and hit F Song Library - Alpha by Artist first name Artist - Alpha by First name Song Title 12 Stones Bulletproof 12 Stones Psycho 12 Stones We Are One 16 Frames Back Again 16 Second Stare Ballad of Billy Rose 16 Second Stare Bonnie and Clyde 16 Second Stare Gasoline 16 Second Stare The Grinch (Radio Edit ) 1975.